Housing and Environmental Sustainability

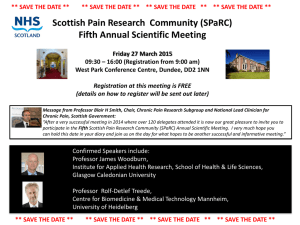

advertisement

24th March 2014 Housing and Environmental Sustainability Introduction 1. This paper is in four main parts: Suggested key issues for the Commission to consider - bullet points under paragraph 2 below A background discussion of why this topic is potentially important for the Commission - paragraphs 3 to 9 Some key facts – paragraphs 10 to 13 A discussion, in more detail, of relevant policies and targets which link into the suggested key issues – paragraphs 14 to 46 Suggested Issues for the Commission to Consider 2. Views of Commission Members are sought on the following points which are discussed in more detail in the body of the paper. Energy Efficiency (paragraphs 14 to 31) Is there a case for suggesting faster progress with insulation work and other energy efficiency measures in existing housing than currently envisaged by the Scottish Government – both on environmental grounds and to help tackle fuel poverty? If so, should we be encouraging more expenditure by the Scottish Government on financial incentives to private owners (and, possibly, social landlords) and, if yes, should any additional expenditure be means tested but with a more generous means test than currently applied, made generally available on a first come first serve basis, used to designate more Areas Schemes or prioritised in some other way? Irrespective of the case for additional funding, should we be suggesting that the Scottish Government should simplify its funding packages, avoiding frequent changes in titles and acronyms and that the Scottish Government should be given responsibility for energy company funding in Scotland so that this can be better integrated with the Government’s own funding schemes? In addition, since it is private owners and tenants who will benefit from lower fuel bills as well as a general community benefit in reduced GHG emissions, should the focus be on using the regulatory powers set out in the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 and, if so, how would these regulations be applied and enforced? Given the apparent limited impact of the Energy Performance Certificates, which are required at the point of sale, are there ways of 1 24th March 2014 making the market work more effectively so that sellers benefit from investment in energy efficiency measures through increased prices? Using the regulatory powers mentioned above to require owners to bring houses up to specified standard before putting them on the market would be a way of building on the EPC concept but it could have indirect consequences for the operation of the housing market. Do members agree that the Scottish Government has adopted a thorough and sensible approach to the upgrading of energy efficiency standards for new housing through the Building Standards Should we be recommending that the Scottish Government adopts a more ambitious approach, with increased targets, for encouraging micro and community power generation by rationalising the financial incentives and giving clear advice on the relevant technologies, what they can deliver for households in different types of houses and parts of Scotland together with estimated costs and savings? Other Operational Emissions (paragraphs 32 to 36) Is there a case for more advice to householders on how to reduce their environmental impacts or is this already covered either through advice on specific topics, for example, advice on recycling or the benefits of active travel or through general, across the board advice? Should the Scottish Government issue stronger central direction/guidance on the need to use brown field land for new housing, for more higher density housing and linking new housing to existing settlements or are these inevitably matters which should be left to local discretion? Even if local discretion is both inevitable and desirable, should there be better monitoring of the impact of current guidance? Alternatively, or in addition to the above, should we be thinking of inviting the Scottish Government to give serious consideration to the ideas for the radical ideas for urban land reform put forward by Professor David Adams of Glasgow University Embodied Emissions (paragraphs 37 to 46) Does it makes sense, from an environmental point of view, to promote refurbishment of existing housing and bringing back empty houses into use where at all possible rather than demolishing and replacing them – notwithstanding the higher levels of energy efficiency achieved by new buildings? 2 24th March 2014 Does it also make sense to seek to limit demolitions, as far as possible, to housing which is technically obsolete and, if so, how can this be achieved? Leaving aside the energy efficiency/ zero carbon building standards (which have been and are under review) should there be a review of other aspects of the Building Standards for new housing which would seek to balance short term extra costs (financial and environmental) against additional longevity and the environmental benefits that might result from this? Other Are there any other matters on this topic which members think we should be taking a view on? Why is this topic important for the Commission? 3. Housing – new construction and the day to day use, repair, maintenance and improvement of the existing stock – can have a significant environmental impact through its use of resources such as energy, land and building materials. 4. Environmental sustainability is concerned with minimising the use of environmental resources to protect the wellbeing of future generations. In short, it is concerned with inter-generational equity. The most quoted definition of sustainable development comes from the work of the United Nations Bruntland Commission’s report in the 1980s: “Sustainable development is the kind of development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” 5. Sustainability in the sense of long term viability which promotes wellbeing is often considered to have 3 interrelated pillars – environmental, economic and social. All 3 are clearly important for the Commission, but this paper focuses on environmental sustainability and this will need to be linked into work on the economic and social aspects of housing policy and practice in due course. 6. Much of the focus of work on environmental sustainability is on the impact of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activity on climate change. This reflects the threat posed to life on the planet for future generations by the current level of emissions. The severity of this threat has led to 3 24th March 2014 international scientific efforts to establish a framework for classifying and quantifying GHG emissions and to set global and national targets to minimise the risk. It is widely accepted that there is a need to reduce global GHG emissions by 80% by 2050 in comparison with 1990 levels to avoid the risk of uncontrollable climate changes in the second half of the 21st century. This target is enshrined in UK and Scottish legislation. In addition, there are targets for intervening years and sectoral targets which are consistent with this overall target, including a target for the residential sector in Scotland. All these targets are monitored by the UK Committee on Climate Change. 7. GHG emissions from housing can be divided into 2 sorts – “operational” emissions which are largely the result of the use of energy in the home for space and water heating and “embodied” emissions resulting for the process of initial construction and any subsequent refurbishment. 8. Although the embodied emissions associated with a new house are relatively high, the longevity of most housing (the Scottish Government estimates that 85% of homes in use by 2050 have already have been built) has meant that operational emissions have been the principal target of housing policy. 9. In addition to GHG emissions which result directly from housing, housing developments can impact indirectly on the environment in a number of other ways, for example: Housing developments on green field sites may lead to a permanent loss of good quality agricultural land which is in short supply in Scotland. Housing developments built at low densities may make it difficult to provide public transport or encourage active travel and, therefore leads to increased car based commuting which, in turn, generates additional GHG emissions. The use of water by households in the home and the arrangements for reuse, recycling and disposal of household waste can impact on GHG emissions and the use of scarce resources. The use of space within housing developments can impact on biodiversity. This paper seeks to cover these topics as well as GHG emissions although it is, in some cases, difficult to quantify relevant impacts on a national basis. Key Facts 10. GHG emissions in the residential sector1 were estimated at 6.6 MtCO2e2 in 2011 i.e. 13.5% of Scotland’s total emissions of 48.8 Mt CO2e. Residential 1 Residential sector GHG emissions largely arise from space and water heating but they do not include emissions from power stations generating electricity 4 24th March 2014 emissions have fallen by 20% since the accepted base year of 1990 as compared with an overall drop for Scottish emissions as a whole of 31% over the same time period. Although there has been a steady fall over time in residential emissions, the actual figure for any one year is very weather dependent and, in 2010, was slightly higher than in 1990. 11. Although not directly an environmental measure, fuel poverty, defined as requiring spending more than 10% of household income on household fuel use to maintain a satisfactory heating regime, increased steadily from 13% of all households in 2002 to 33% in 2009 and has since fallen to 29% in 20113. This increase in the number of households in fuel poverty undoubtedly reflects the substantial increases in fuel prices in this period. 12. There have been significant improvements in home insulation, admittedly from a low base, and replacement of central heating boilers with more efficient equipment. By the end of 2011 only 2% of homes had no loft insulation, although less than half (45%) had the recommended 200mm depth of insulation, and two thirds of cavity walls had been insulated. Approximately 5% of households upgraded their central heating boilers in 20114. Nevertheless estimates of the realistic potential for insulation work and other domestic energy saving measures published by the Scottish Government in 20075 are substantially higher. In total the costs of these works (in current 2007 prices) was estimated at £16 billion which would yield cumulative savings of £35 billion by 2050. This cost covers cavity wall and loft insulation, glazing improvements and short term upgrades of 100% of the realistic potential and solid wall insulation of just under half of the realistic potential stock. In addition allowance is also included for boiler upgrades, and the installation of solar water heating and other forms of domestic renewable energy. Overall, these improvements were estimated to reduce residential GHG emissions by 42%. 13. Other relevant factual material on environmental impacts is difficult to find: The Countryside Survey estimated that the built up area of Scotland increased by some 2,000 hectares from 1998 to 2007 but it is not clear how much of this was due to housing development. 6 2 GHG emissions are normally quantified in terms of millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents. This takes account of all greenhouse gases which are weighted according to their impact on global warming. 3 Scottish House Condition Survey Key Findings 2011 4 All figures taken from Scotland’s Sustainable Housing Strategy, Scottish Government 2013 5 Consultation on the Energy Efficiency Plan for Scotland, chapter 6, figure 6.7 6 Countryside Survey. Scottish Government land use statistics. This change was not statistically significant. 5 24th March 2014 The Scottish Derelict and Vacant Land Survey recorded almost 11,000 hectares of derelict and vacant land in Scotland in 2012 – a figure which has not changed much in recent years.7 . Current Policies and Associated Policy Targets Operational Emissions - Energy Efficiency and Micro Generation Policy Targets 14. The Scottish Government currently has a number of policy targets in this area. In terms of outcomes, the 2 key targets are: To make a full contribution to the Government’s GHG reduction targets i.e. to achieving the 80% reduction by 2050 (as set out in the Climate Change (Scotland)Act 2009 and interim targets;8 To ensure that no-one in Scotland has to live in fuel poverty, as far as reasonably possible by 2016 – as set out in the Housing (Scotland) Act 2001. In terms of outputs, the relevant milestones are to ensure by 2020 that: Every home to have loft and cavity insulation where this is cost effective and technically feasible Every home with a gas fired central heating boiler to have a highly efficient one with appropriate controls At least 100,000 homes to have adopted some form of individual or community renewable heat technology. Recently a further objective has been added for 2030. To deliver a step change in provision of energy efficient homes through retrofit of existing housing and improved building regulations. 15. It is probably premature to attempt to assess success in achieving GHG emissions. The Scottish Government does not publish sectoral targets, but the overall target for Scotland was missed in 2010, largely, it is argued, because of the exceptionally cold winter, whereas the 2011 figures show the overall target being exceeded. Within this total picture, the residential sector achieved proportionately less reduction than Scotland as a whole. The position on fuel poverty seems much worse. Given that over 25% of all households were in fuel poverty in 2012, it seems very unlikely that the 2016 target can be met. 7 8 Area of Vacant and Derelict Land, Scottish Government. An interim target of 42% was set for 2020 and there are also annual targets for the period up to 2022 6 24th March 2014 Current Policy Measures 16. The Scottish Government has a number of policy levers it can use ranging from advice, financial assistance and regulation. 17. Financial assistance towards the cost of insulation measures and, in some cases, for installing or replacing central heating boilers, has been available for some time through a complex and changing range of schemes with funding provided directly from the Government or through energy company obligations. The current schemes are known as the Home Energy Efficiency Programmes for Scotland (HEEPS) and the Energy Company Obligations (ECO) and the intention is to implement Area Based Schemes targeted at areas with high levels of fuel poverty alongside national schemes to provide for the most vulnerable households i.e. those dependent on social security benefits, wherever they are. 18. The Scottish Government intends that these programmes should spend in the order of £200m per annum but only £79m was allocated directly from the Scottish budget in 2013/14 and the remainder is to come from the rather less certain funding contribution from ECO which operates on a UK basis and is managed by the main energy companies with funding from a levy on fuel bills.9 Following concerns about rising fuel prices, the funding for ECO schemes was reduced at the end of 2013 19. The Area Based Schemes have been selected by local authorities who have each been given an allocation by the Scottish Government based on a formula which reflects the level of fuel poverty in their areas and the number of hard to treat properties. Most areas selected by local authorities are mixed tenure areas, although it is only the private owners who are eligible for grant assistance. There are no precise estimates of the number of households who might benefit but the Scottish Government estimates that it might be in the range OF 15,000 to 20,000. Local authorities are encouraged to use these schemes to insulate solid wall properties and those with difficult cavity walls (collectively known as “hard to treat”) and owners can receive up to £7500 from HEEPS plus, possibly some extra, funding from ECO. 20. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the existing arrangements for providing financial assistance for energy efficiency work by private owners is confusing and fragmented. There have been some 6 schemes since 2009/10 with often similar objectives but different names, acronyms, terms and 9 The Energy Company Obligation is targeted at households. There is a an additional UK scheme called the Green Deal scheme which provides loan funding for energy efficiency improvements which are the repaid by a supplement to fuel bills. 7 24th March 2014 conditions. The split of funding between the Scottish Government and the energy companies does not help for joined up policy. . 21. In terms of regulation, the Scottish Government included certain energy efficiency measures in the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) to be achieved by 2015 although these were seen to be relatively modest and a new Energy Efficiency Standard for social housing, to be achieved by 2020, has recently been subject to consultation. The main concern for social landlords is how the cost of these additional requirements will be met. 22. The new Energy Efficiency Standard for Social Housing will be implemented using the powers given to Scottish Ministers under the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 to make regulations to require owners to bring their houses up to a specified standard. In principle, these powers could be used to require owner occupiers and private landlords to upgrade the energy efficiency of their houses and the Government plans to consult on draft regulations in 2015. Any such regulations would require difficult decisions about the appropriate standards, how they would be enforced and whether there would be a different approach to private landlords as opposed to owner occupiers. 23. Finally in relation to regulation, the Government specifies standards for new buildings in the Building Standards and there has been a progressive improvements in the required energy efficiency standards and a further, revised standards are planned for 2014. The improvements are following a trajectory originally set out in the Sullivan Report10 published in 2007. This has 4 stages - improvements in energy efficiency standards in 2010 and 2013 (now postponed until 2014), to achieve a 30% and 60% reduction in energy use compared with the 2007 standards, subsequent improvements by 2016/17 to achieve net zero carbon buildings (i.e. where there are no net emissions from water and space heating, light and ventilation and, finally, by 2030 an ambition to have total life zero carbon buildings i.e. where are net zero emissions over the whole life of the building taking into account embodied carbon. 24. In terms of advice, the Scottish Government funds the Energy Savings Trust’s Home Energy Scotland Advisory Network which provides advice to households over the phone or through its website. Typically, this is advice on grant assistance and potential contractors. 10 A Low Carbon Building Strategy for Scotland, Scottish Government 2007 8 24th March 2014 25. A rather different form of advice is provided through the Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) which are part of the Home Reports which all sellers must provide to potential purchasers when their house is put on the market. They provide an overall assessment of energy efficiency and suggested possible measures. Although this was intended to be a means of transforming the market, the information provided tends to be standardised and formulaic. There has not been any systematic research into the success of EPCs although a review of Home Reports as a whole is planned, but the Scottish Government accepts that the value of energy efficient homes is not reflected in higher property values or more favourable lending terms. Micro and Community Power Generation 26. This is a second and, relatively minor, strand in the Scottish Government's strategy. Micro generation encompasses a range of power generation technologies that can, in the right circumstances, at the domestic scale. These can include, for example, solar panels, ground source and air source heat pumps, small windmills and biomass fuelled boilers. Community schemes can generate sufficient power to supply a number of houses. 27. The Energy Savings Trust estimates that some 11,000 micro-heat technologies had been installed by 2012. The Government's Sustainable Housing Strategy sets a target of at least 100,000 homes having adopted some form of individual or community renewable heat technology by 2020 i.e. around 4% of the stock. 28. There is a somewhat confusing array of financial incentives to encourage micro generation including a Scottish Government Home Energy Renewables Loan Scheme and a Renewable Heat Premium Payment from the UK Government and these can be combined. There is also the possibility of assistance under the Green Deal and payments under the "feed in tariff" if electricity is supplied to the grid. Local authorities and RSLs can obtain loan finance from a separate Warm Homes Fund for micro and community renewable. Energy Efficiency Policies – Conclusions 29. The various grant schemes that have been available linked to the Energy Savings Trust advisory network has certainly encouraged both cavity and loft insulation works by owner occupiers and there is a general move by consumers towards more efficient boilers as old ones are replaced. Social landlords have also invested in energy efficiency works in their housing. This is reflected in the energy efficiency ratings recorded over time by the Scottish 9 24th March 2014 House Condition Survey which show the percentage of the stock assessed as having a “good” rating increasing from 40% in 2003/04 to 65% in 2011; for socially rented housing the improvement has been from 56% to 76% over the same period. In general, the poorest energy efficiency is found in the private rented sector but even there 52% was assessed as good in 2011. 30. Despite these improvements, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, to date, the various policy measures described above have largely impacted on the “low hanging fruit ” i.e. loft insulation and the houses where it is easier to install cavity fill insulation. . It is also not clear how good a good rating actually is i.e. does it achieve all the realistic potential for insulation or is just relatively better than poorer insulated housing. The Scottish Government’s estimate of £16b to be achieved by say 2030 to achieve the full potential would require £700m expenditure overall per annum. 31. In relation to micro renewables, the current target is relatively modest and more might be achieved with a simpler financial incentive structure and more and better information for the public about what is possible and its benefits. Other Operational GHG Emissions 32. As mentioned above, other operational GHG emissions associated with housing are linked to the use of water by households, the disposal of household waste and transport from the home to work, shopping centres and leisure facilities. The general drift of the changes required to reduce household emissions from these sources is clear – reductions in the use of water through advice and water metering, reduction and recycling of household waste; and increased use of public transport and active travel – but a comprehensive analysis of policies and impacts is beyond the scope of this paper. 33. It has been suggested that the Commission should be considering the case for targeting new building on brown field as opposed to green field sites and prioritising higher density housing as a means of reducing environmental impacts including GHG emissions. In both cases, this is largely a matter for national and local planning policies. 34. At the national level, the relevant guidance is set out in the Housing chapter of Scottish Planning Policy11. This suggests that development plans should: Scottish Planning Policy – the statement of the Government’s policy on nationally important land use planning matters, Scottish Government, February 2010 11 10 24th March 2014 Allocate a generous supply of land for housing with a minimum of 5 years effective land supply maintained at all times and an indication of the possible scale and location of land up to year 20 Set out a settlement strategy taking account of factors such as investment in infrastructure; accessibility of services, employment and open space; protection of the landscape, bio-diversity, cultural heritage; flood risk etc Promote the efficient use of land by directing development towards land within existing settlements where possible and considering the use of previously developed land before development on greenfield sites Determine the density of new development in relation to the character of the place and its relative accessibility with higher densities appropriate at central and accessible locations using good design to achieve higher density living environments without overcrowding or loss of amenity. Meet the majority of housing land requirements within or adjacent to existing settlements. 35. This is clearly generalised advice with a strong flavour of “motherhood and apple pie” with the result that, rightly or wrongly, land use policy for new housing is being determined at local level in response to local development and planning applications. In any event, the overall environmental impact, positive or negative, is relatively limited because the current level of new building only adds marginally to the total stock. For example, the total amount of new house building in 2012 was only 0.6% of the existing stock. As there is no national recording of the land used for new house building or the density of new developments, it is impossible to monitor the position yet alone estimate the environmental effects which will vary considerably from area to area and site to site. 36. Nevertheless, the statistics on urban derelict and vacant land in Scotland indicate that this amounts to some 11,000 hectares and this figure has not changed much since 200112. This represents a considerable underused resource and suggests that more than advice and guidance to direct development to brown field land may be required. David Adams13 from Glasgow University has looked, in depth, at the way in which the market in derelict and vacant land fails to achieve development. These can include ownership constraints (multiple or fragmented ownership, ownership unknown or owner unwilling to sell), valuation problems caused by the lack of comparators and the lack of interest in development on the part of some landowners. He argues that the traditional remedy of compulsory purchase 12 The research by David Adams (see below) indicates that this total is not static and that, each year, some vacant and derelict land is developed and new sitesbecome vacant or derelict. 13 The Potential for Urban Land Reform in Scotland - David Adams, University of Glasgow, paper given to AESOP-AGSP Congress, Dublin July 2013. 11 24th March 2014 by a public authority are rarely used because the procedures are bureaucratic, expensive and time consuming, or perceived to be so. He recommends that consideration should be given to 3 proposals for promoting urban land reform in relation to derelict and vacant land a community right to sell by public auction when there is a demonstrable public interest majority land assembly - when the developer has acquired a large percentage of the land, he would have the right to acquire the remainder compulsorily (as is the case apparently with company takeovers) owner participation in development - essentially a land readjustment or pooling process to allow fragmented plots owned by those in favour of redevelopment to be consolidated and serviced whilst still owned privately. Embodied Emissions 37. The amount of GHG emissions given off during the process of building new houses or rehabilitating existing ones will obviously vary, to some extent, from one house or rehabilitation project to another. These can only be calculated using life cycle analysis which attempts to measure the carbon input in all stages of the process of production of new and refurbished housing. There has been only a limited amount of work of this nature in relation to housing. 38. One such study funded by the Empty Homes Agency14 calculated that each new home included in its study 50 tonnes of CO2e so that, if this figure is reasonably correct the 15,000 houses built in 2012 would have generated 0.75 Mt CO2 i.e. approximately 11% of the annual operational emissions created by the use of energy in the home. 39. The same study estimated that the refurbishment required to bring an empty home back into use was about 15 tonnes of CO2e i.e. 30% of the carbon input into a new house, although this is likely to vary more than the carbon input into new houses which must all conform to the current Building Standards. The higher standards of energy efficiency required in new housing will reduce operational emissions, but the Empty Homes report suggests that it would take several decades and generally more than 50 years for this to offset the lower carbon input into rehabilitation. New Tricks with Old Buildings – reusing old buildings can cut carbon emissions” Empty Homes Agency, March 2008. This work was based on 6 case studies. 14 12 24th March 2014 40. A more exhaustive review of the existing literature would be required to compare these calculations against other life cycle analyses. But they are supportive of the common sense view that it makes good environmental sense to attempt to retain as many existing houses as possible, for as long as possible, rather than demolish and replace them routinely after a fixed period or, for example, when any debt on the initial construction has been paid off. 41. Compared with the number of demolitions in the 1960s and 1970s, recent decades have seen much lower levels. Since 2000, the number of recorded demolitions has varied between 3,000 and 6,000 per annum 15 and the majority of these are thought to be former social rented houses. Some will be technically obsolete, for example, certain types of industrialised housing constructed after the second world war, but most are likely to be simply not socially sustainable i.e. very unpopular primarily for social and economic reasons. A more elaborate explanation is summarised in the quote below: Across the UK, the presumption against social housing has allowed demolition to be regarded as the solution to a whole range of problems, many of which have little relationship to the physical fabric of the buildings being demolished, but are rather a function of wider underlying social problems and of failures in management and maintenance. (Carley, 1990) Demolitions can have a compounding effect on remaining housing: the rental base is reduced while historic debts remain, and the resulting financial constraints can mean that other homes are left to deteriorate to a state where they too are considered fit only for demolition. (Scottish Executive, 2003) Some social housing does indeed need to be demolished, but this is the minority. Much of the rest might not be of the form we would choose to build today, but can, nevertheless, provide good homes for relatively little extra investment. (Stuart Hodkinson, in Glynn 2009a; Glynn 2011) Demolition does not only reduce the social housing stock. It disrupts lives and breaks up communities. It is a long drawn-out and messy process that can produce a lot of individual hardship, especially when, as is often the case, it involves elderly and long-established households16 42. In principle, therefore, it ought to be possible to reduce the level of demolitions and, consequently, the need for replacement housing especially in the short to medium term. However, housing is a consumer good, albeit one with a long life and, in the long term, the level of demolition and replacement may need to increase because the parts of the housing stock are in such poor condition that refurbishment is not an economically viable 15 Statistics on demolitions are published by the Scottish Government but with a warning that local authority returns (from which the national figures are compiled) may underestimate private sector demolitions. 16 Mass Demolitions and Growing Housing Waiting Lists – Sarah Glynn 2011. This is a paper given by the author to a seminar at the University of Helsinki in 2011 and which draws on her research in Dundee, 13 24th March 2014 option. But it is difficult to go beyond this very general assertion since modelling obsolescence in the Scottish housing stock would be a very complex task and well beyond the scope of this paper. 43. It has been suggested that the Commission might wish to consider the case for increasing the quality of new housing as a way of improving its longevity and, thereby, making it more environmentally sustainable. The Building Standards17 apply to all new houses and to conversions and is, therefore, the obvious mechanism for achieving higher standards. The standards relate to the structure of the building, prevention of fires, energy use, other environmental matters, noise, and safety including access to and inside the dwelling. 44. Through the work of the Sullivan Committee (see paragraph 23 above), the Government has endorsed a road map for achieving “total life zero carbon buildings by 2030 i.e. where there are net zero emissions over the whole life of the building taking into account embodied carbon. 45. Apart from these proposed, radical changes, there are 2 aspects to the standards which are particularly relevant for “future proofing”. Firstly, there are standards which facilitate the use of the house for persons with disabilities and are particularly relevant to the concepts of “lifetime homes” or “barrier free” housing. The Building Standards include access standards which are relevant to this debate. Secondly, there is a debate about the need for minimum space standards. These were included in the Building Standards (based on the Parker Morris report) up to 1987 when they were removed although they were retained for publicly funded housing which in recent years has been subject to standards set out in “Housing for Varying Needs” originally published by Scottish Homes18. There is, therefore, a potential gap in relation to private housing.19 46. Whether there is a need for any further rationalisation or enhancement in standards and what this would cost are detailed technical matters beyond the scope of this paper. But the UK Government has published a Code for Sustainable Housing which applies to new housing in England and Wales, based on technical work by the Building Research Establishment, and it 17 The Building Standards for Scotland comprise statutory Building Regulations supported by published Technical Handbooks for domestic and non domestic buildings. The most recent Technical Handbook for Domestic Buildings was published in 2013 18 Housing for Varying Needs” Scottish Homes, 2004 19 The UK Government has recently gone out to consultation on a proposal to rationalise design standards for new housing in England and Wales by adding space standards to their Building Standards. Some commentators have argues strongly that these should be based on an updated version of Parker Morris. 14 24th March 2014 might be helpful to check whether there are items included in this Code which are not properly covered in the Scottish Building Standards. Richard Grant March 2014 15

![Greener Scotland Board [or Greener Outcomes Engagement Board]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005835939_1-8db527d20524850542a118c4b1f3949a-300x300.png)