History of Community Symbols and Loss AB

advertisement

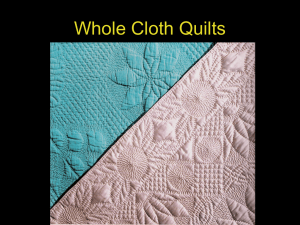

History of Community Symbols and Loss this is a terrible header Quilting, especially in America, has long been a community advocacy event (Moxley, Feen-Calligan, Washington, & Garriott, 2011). In the early days of America, quilting was a way for communities to come together, often in response to, or preparation for, a significant life event. In more modern times, quilts have become intentional pieces of advocacy for marginalized populations. The AIDS Quilt exemplifies this trend towards overt activism. Started in 1987 by the NAMES project, the AIDS quilt has grown exponentially in the last three decades (Pearl, 2009). This quilt has been displayed across the country, and gives voice to individuals stricken with AIDS. The AIDS quilt also doubles as a memorial for those who die from the disease. Through the quilt, their living memory marches on, speaking from their silence. As a more concrete example of memorialization and commemoration, the Vietnam Wall Memorial in Washington D.C. enshrines the names of some 58,132 individuals who died in conflict in Vietnam (Sturken, 1991). The wall itself has little more than the names of the individuals inscribed on its surface. Nevertheless, the wall has become a place of commemoration where visitors interact with the memory of the lost and leave gifts of all kinds (Junge, 1991). Clearly, a physical space or item crystalizes the commemorative remembrance for the survivors of loss, and provides a place to safely voice pain and injustice. Quilting activity Historically, quilts were made by groups of women as gifts before migrations, after births, or to wrap loved ones for burial (Moxley et al., 2011). All of these events are significant life changes. That quilts should be the chosen token points to the power of communally produced artifacts. Quilts often come to represent the community that has constructed them. In the past, this meant holding family members close, even after migrating to the frontier. The same use of a quilt as a representation of the community occurs in the homicide loss survivors group. The faces on the quilt help the members of an unspeakably terrible club to join together and speak their terror. The [what are we calling our quilt?] quilt allows members of a marginalized community to stand forth and state, this murder happened, to my loved one, I am forever changed. Because of the stigma associated with this type of loss, this speaking out is not easily achieved conversationally. Thus symbols stand in for words. AIDS quilt In the 1980’s AIDS was believed to be an affliction of the homosexual community (Pearl, 2009). Thus, the disease marginalized individuals who already lived outside of the mainstream. As the quilt developed and grew it became a space for individuals to commemorate and value lives that were lost with little recognition by the society at large. Because the mainstream culture considered AIDS to be an affliction of the marginal minority gay culture, little press or attention was given to the lives and stories of the individuals. The quilt itself is a portable, tangible, and lasting item that speaks stories which would otherwise remain untold. Vietnam wall The Vietnam wall serves a similar purpose. This wall has become a touchstone for all those who want to remember the lives lost during the police action in Vietnam. Individuals leave flowers and other items at the wall as a tangible commemorative act. Often times individuals may not even know any one listed on the wall personally. Never-the-less, these gifts testify to the power of a physical space in the precess of humans commemorating loss. The wall normalizes the grief and provides a space to interact with the pain. Furthermore, visitors to the wall can do something concrete as a response to their grief. In both of these examples, the accommodation of loss is demonstrably helped by the provision of physical spaces and concrete actions conducted by survivors of the loss. References Moxley, D. P., Feen-Calligan, H. R., Washington, O. G., & Garriott, L. (2011). Quilting in selfefficacy group work with older african american women leaving homelessness. Art Therapy, 28(3), 113-122. Pearl, M. B. (2009). American Grief: The AIDS quilt and texts of witness. GRAMMA, 16, 251272 Sturken, M. (1991). The wall, the screen, and the image: The Vietnam veterans memorial. Representations, 35, 118-142. Junge, M. B. (1999). Mourning, memory and life itself: The AIDS quilt and the Vietnam Veterans' Memorial Wall. The Arts in psychotherapy, 26(3), 195-203.