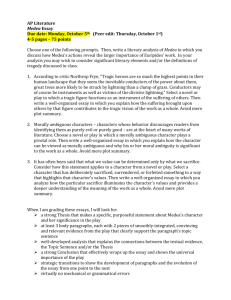

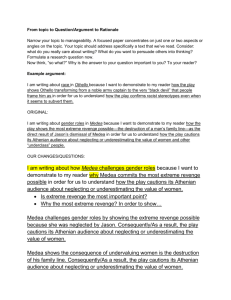

13 Chapter 4 - Dramatic Structure

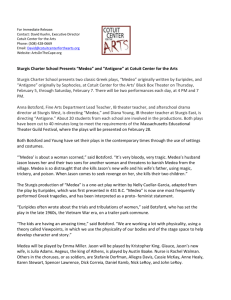

advertisement