Children`s Law Centre Mental Capacity Bill Briefing Paper

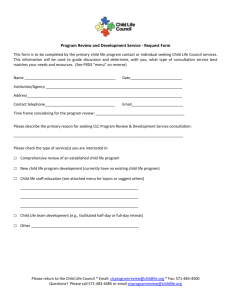

advertisement