Chapter 22

advertisement

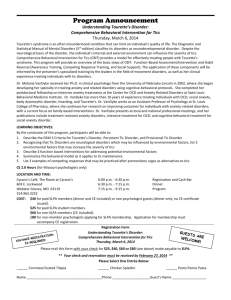

DISORDERS OF NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT Acknowledgements: Most of the information included in this chapter was obtained from the Handbook of Psychiatry, 2005, Mental Health Information Centre of SA, Department of Psychiatry, University of Stellenbosch. Chapter by Professor Susan Hawkridge, Dr Linda Keyter and Dr Bennie Steyn A. EATING DISORDERS Pica This is the culturally and developmentally (i.e., after 18 months) inappropriate eating of non-nutritive substances (e.g., paint, soil) for at least one month, in the absence of another major psychiatric disorder and severe enough to warrant clinical attention. When it occurs exclusively in the course of another psychiatric disorder, such as schizophrenia, then the additional diagnosis of pica is only made if the problem is severe enough to warrant independent attention. Rumination disorder The infant starts to re-chew its food and appears to find the experience pleasurable. There is often weight loss or failure to gain weight and the condition may in rare cases be fatal. The infant is characteristically hungry and irritable between episodes of rumination. Feeding disorder of infancy or early childhood This is a heterogeneous diagnostic group for children under 6 years who present with persistent weight loss or failure to gain weight for at least 1 month that cannot be ascribed to a general medical condition, other psychiatric disorders or one of the above disorders. Sufficient food must be available. Thorough physical examination is important and if no cause is found, such children should preferably be referred for evaluation. B. SLEEP DISORDERS IN CHILDREN Sleep-related problems are common in children and adolescents. Behavioural, psychiatric and general medical factors can all contribute to sleep problems, which can in turn exacerbate emotional and behavioural problems. Parental anxiety over children’s sleep patterns is established early in the child’s life, as it influences their own sleep patterns, and the problem is frequently brought to the attention of professionals. When a change in a child’s sleep pattern is reported, it may be a normal developmental variation, a transient phenomenon or a sign of a specific sleep disorder or psychological or emotional disorder. Only 4 conditions will be discussed in this chapter, namely primary insomnia, nightmare disorder, sleep terror disorder and sleepwalking disorder. 1. Primary Insomnia Problems falling asleep and nocturnal wakefulness are more common in the toddler and preschool years, and if they are still present by the age of 3 years, there is a good chance that they will persist and be associated with later behavioural problems. Many factors are associated with insomnia in children, viz. the infant’s temperament, nutritional state, milk allergies, marital discord, etcetera. Parent-infant interaction around bedtime may determine later sleep problems. Infants who fall asleep in their own beds are more likely, if they wake later in the night, to return to sleep on their own. Infants who fall asleep in the early evening away from their own beds are more likely to need to repeat the routine in order to fall asleep again. Often the insomnia is precipitated by an illness or an external factor, but if it becomes a focus of anxiety for the parents or the child, a chronic sleep problem may develop. 2. Parasomnias a) Nightmare disorder:3 Nightmares occur during REM sleep, and usually wake the child. The child remembers what he was dreaming about, and is able to recount it the following day. Nightmares may occur more frequently with stress or a change in the environment, but alone are not a sign of psychopathology in children. Parents may wake a child during a nightmare without any untoward effects. b) Sleep terror disorder (Pavor Nocturnus):3 This occurs in 1-6% of normal children, more frequently in boys than in girls. There is often a family history of parasomnias. Onset is usually between 4 and 12 years old, and the condition is not associated with any particular psychopathology. The episodes occur in stage 3 and 4 of non-REM sleep, and on EEG are associated with delta activity. The child screams in a terrified manner, and sits upright with objective signs of anxiety: sweating, tachycardia, dilated pupils, etcetera. He does not react to the parent’s attempts to comfort him or to wake him, and often the scream is followed by an episode of sleepwalking. If the child does wake, he is usually disorientated. Most often he will return to sleep immediately after the terror has dissipated. When he wakes again, he will remember very little or nothing of the episode. Parents are usually extremely anxious following such occurrences. Treatment involves reassurance of the parents that this disorder is not dangerous or traumatic to the child. c) Sleepwalking:3 As with sleep terror disorder, episodes of sleepwalking occur in stages 3 and 4 of non-REM sleep. Onset is usually between 4 and 8 years, again more frequently in boys. The child may carry out a series of stereotypical actions, including walking, dressing, going to the toilet, talking or screaming. The child is unresponsive during the episode, and when he wakes will remember nothing of it. It is not a sign of another psychiatric disorder, but may well be exacerbated by stress, severe fatigue and recent sleep deficit. Often a family history of parasomnias will be found. Treatment is only necessary when there is a danger of self-injury. The child’s safety should be ensured and a neurological consultation is recommended. C. ELIMINATION DISORDERS Enuresis It is characterised by repeated voiding of urine (wetting the bed or clothes) during the day or at night. It must be clinically significant (i.e., at least twice a week for at least three months) or cause clinically significant distress or impair functioning. The diagnosis is not made before the chronological or mental age of 5 years and the term enuresis is not applied when urinary incontinence is the result of a general medical condition or a substance (e.g., a diuretic). Enuresis can occur at night, during the day or both. Encopresis The essential feature of encopresis is the passing of stool, usually unintentionally but sometimes voluntarily, in inappropriate places (e.g., in clothes or on the floor). It must be clinically significant (i.e., occurring at least once a month for at least three months) or cause clinically significant distress or impairment in functioning. The diagnosis is not made in a child who has not attained the chronological and mental age of 4 years, and does not include faecal incontinence due to a general medical condition or a substance. It can occur with or without constipation and overflow incontinence. Even children in whom there is a physical cause for faecal incontinence are often referred to child psychiatry because a strong reaction from the child’s mother has exacerbated the problem and secondary emotional problems have supervened. D. MOVEMENT DISORDERS AND TOURETTE’S DISORDER Tic disorders Ten percent of children at times have transient involuntary facial movements. As in all movement disorders these movements (“tics”) are exacerbated by stress, but they are not necessarily a sign of psychopathology. When we speak of tic disorders, we refer to the presence of tics to such a degree that there is impairment of the child’s social or academic development. It is generally accepted that such disorders are neurological in nature, but some children who suffer from them will still require referral to child psychiatry owing to psychiatric comorbidity and secondary emotional problems. A “tic” is an involuntary, sudden, repetitive, stereotyped movement or vocalisation. It is rapid and non-rhythmic in nature. It occurs involuntarily, but can be temporarily suppressed. An incidence of 4 -5 per 10 000 has been reported. Boys are affected more often than girls. Symptoms usually begin around 7 years of age and in the great majority of cases the diagnosis is made before the age of 14 years. Particularly in the case of late onset of symptoms, a thorough neurological examination must be carried out. Vocal tics usually begin later than motor tics. Motor and vocal tics or a reliable history of tics must be present for the diagnosis of Tourette’s disorder to be made. Great confusion is caused when children who present with single symptoms, behavioural disorders or disorders usually comorbid with Tourette’s disorder are labelled as having “Tourette’s disorder”. Comorbidity occurs in a large percentage of children with tic disorders. Fifty percent will have obsessive-compulsive disorder or behaviour. This will usually warrant independent treatment and consultation with an expert in the field is recommended. AD/HD can be diagnosed in 40% of these children – usually prior to the onset of tics. Consultation with an expert in the field is mandatory. Depression and poor self-esteem are common in any child who has a chronic disorder that makes him appear “different” from his friends. Many children with Tourette’s disorder suffer emotional damage, especially in the early stages of the disorder when parents and teachers have little or no knowledge of the disorder. Children are frequently punished for this persistent behaviour. These children are frequently teased and mocked by other children. They are also often punished by parents and teachers because their behaviour is disruptive and appears to be voluntary. The child experiences this as unfair, because although the tics can be suppressed for short periods, it is impossible for a child to do this for more than a few minutes. The child feels helpless and angry, and may react with disruptive behaviour, depression or irritability. In adolescence the average child already has enough problems with self-image, and the additional burden of a disorder that may make the child appear “abnormal” or even “mad”, may give rise to social isolation, severe depression or behavioural disorders. References 1. Garfinkel PE. Feeding and eating disorders of infancy and early childhood. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry/VI. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkens, 1995:23212324. 2. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition). Washington: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. 3. Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Synopsis of psychiatry (9th Edition). Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkens, 2003:760-781,1241-1258. 4. Anders TF, Giben LA. Pediatric sleep disorders: A review of the past 10 years. JAACAP 1997;36:1. 5. Robertson BA. Handbook of Child Psychiatry for Primary Care. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 1996. 6. Mikkelsen EJ. Elimination disorders. In: Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry/VI. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkens, 1995:2337-2343. 7. Mikkelsen EJ. Modern approaches to Enuresis and Encopresis. In: Lewis M, ed. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkens, 1996:593-601.