Transcript of Critical Thinking Workshop Video

Transcript: An introduction to Critical Thinking

Work shop by: Jim Skypeck

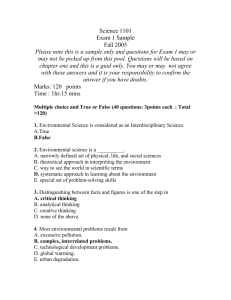

Hello, and welcome to my workshop on an Introduction to Critical Thinking! What is Critical Thinking?

There is a wonderful organization called the Foundation for Critical Thinking, and they define Critical

Thinking as the ability and disposition to improve one’s thinking by systematically subjecting it to intellectual self-assessment. Basically, this is saying: don’t take your learning passively, question what

you are taught, what you are thinking, and the biases that you may have. Perhaps you are making assumptions that you should be made aware of. As you become aware of your critical thinking, your thinking becomes more honest and intellectually humble.

Now, let’s talk about the evaluation of knowledge: how do you know what you know? Where does

your information come from? Was it learned from your parents? Friends? Teachers? Printing materials, perhaps? Maybe books you had to read for school, or even books you might have chosen to read on your own TV? Online? Have you ever thought about this information and wondered if it’s true or accurate? Have you ever asked yourself “How did they do that?” or “This doesn’t sound quite right”? If you haven’t asked these questions, why haven’t you asked yourself these questions? Well, as learners, most people assume that they “don’t know enough”. More times than not, we assume that the people

giving us our information are experts, and it is usually our instinct to as the saying goes: “trust the experts”. And as a result we never give our information much thought.

There are usually several different lenses we employ to evaluate the credibility of the information we have: accuracy, authority, objectivity, currency, and audience.

When it comes to accuracy of an information source we ask questions like: is the information true? Can the information be verified elsewhere?

When it comes to looking at authority, we are asking if the person who has published the article or book has the credentials or the experience that qualifies them to write or speak on their subject. We ask questions like: does the author have the necessary credentials to be talking about this subject?

When it comes to objectivity, we are looking at if the author has any biases that cause them to share their information in a specific context. We might ask questions like: Is there bias, and if there is how explicit is the bias?

When it comes to currency, we are looking at the longevity of the information, and if the information itself is still relevant to our social situation today. We might questions like: “how current is this information, and is it valid?

And finally, when it comes to talking about audience, we are asking who the information is intended for. Most of the time the intended audience of the writer gives us more understanding of why the author is addressing the information and the biases that he or she may have. We

might ask questions like: to whom or for who is the audience writing? Is the writing for general consumption or for certain academic individuals?

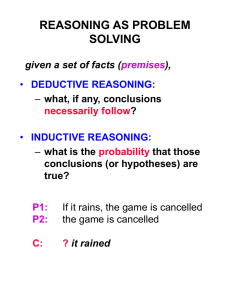

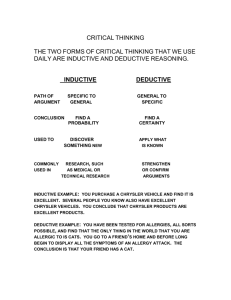

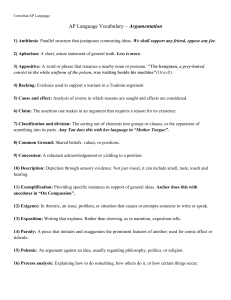

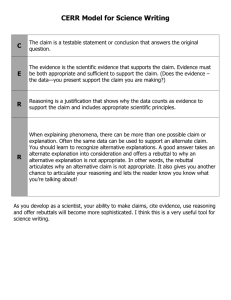

Arguments are organized in three parts: a premise, reasoning, and a conclusion.

A premise is often a statement of identification. For example, a self identifying statement would be: “I am human” OR “all human beings are mortal”.

The conclusion, therefore, is drawn from the premise(s). In this case, the conclusion that is drawn here is that: “I am mortal”.

Finally, the reasoning, is how we get from the premise to the conclusion.

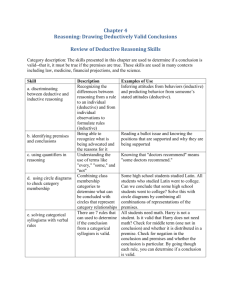

There are 4 primary rules to follow in evaluating if the arguments being made are credible:

1) Premises are either true or false.

2) Reasoning that leads from premises to conclusion is valid or invalid.

3) Correct premises plus valid reasoning equal a sound argument

4) Incorrect premises OR invalid reasoning render and argument unsound.

Therefore, when it comes to how we understand and respond to any type of information, we must remember that all information exists to meet specific needs. All information:

Always has a purpose

Is intending to solve a problem or answer a question

Starts with an assumption (or premise)

Is done with a specific point of view

Is based on data, research, or evidence

Is expressed and shaped by concepts and ideas

Contains inferences from which we draw conclusions

Has implications or consequences

Keeping these factors in mind, it becomes necessary, when considering information, to evaluate the standards of the author’s reasoning. Clarity is the most important question, in terms on if you as the reader and researcher can understand what is being said. Helpful questions that can guide in your evaluation of your own clarity on the subject might be questions like: Is the author clear? Is further explanation necessary? What is the researcher really saying?