The Culture of Thin Bites and Television … Anne

advertisement

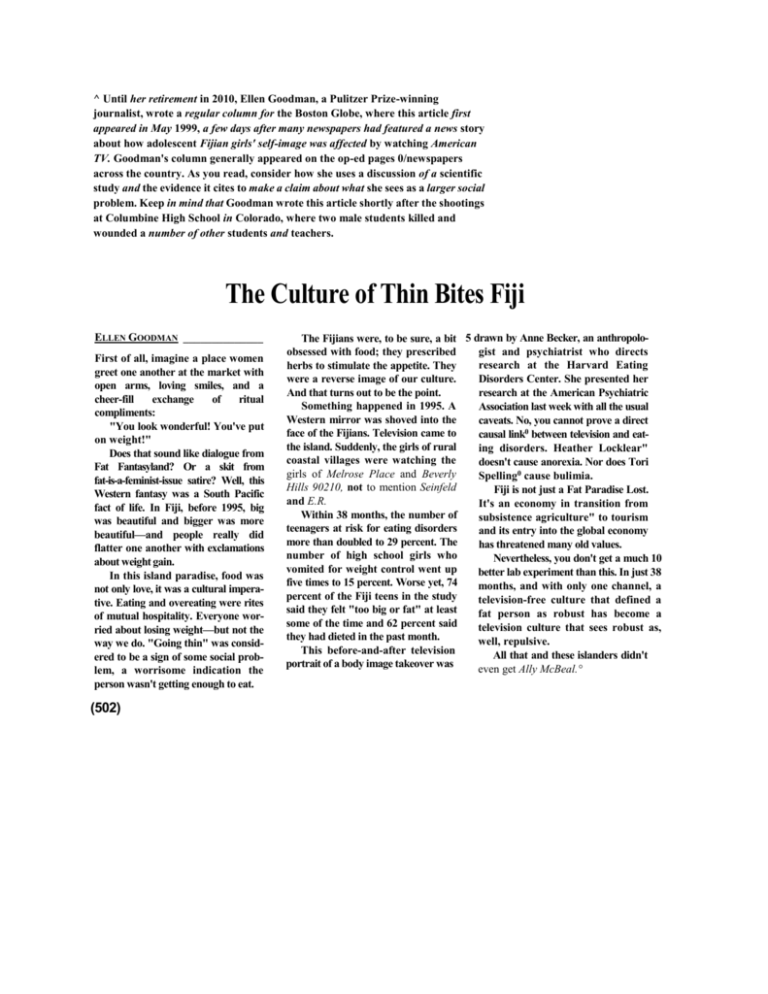

^ Until her retirement in 2010, Ellen Goodman, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, wrote a regular column for the Boston Globe, where this article first appeared in May 1999, a few days after many newspapers had featured a news story about how adolescent Fijian girls' self-image was affected by watching American TV. Goodman's column generally appeared on the op-ed pages 0/newspapers across the country. As you read, consider how she uses a discussion of a scientific study and the evidence it cites to make a claim about what she sees as a larger social problem. Keep in mind that Goodman wrote this article shortly after the shootings at Columbine High School in Colorado, where two male students killed and wounded a number of other students and teachers. The Culture of Thin Bites Fiji ELLEN GOODMAN ______________ First of all, imagine a place women greet one another at the market with open arms, loving smiles, and a cheer-fill exchange of ritual compliments: "You look wonderful! You've put on weight!" Does that sound like dialogue from Fat Fantasyland? Or a skit from fat-is-a-feminist-issue satire? Well, this Western fantasy was a South Pacific fact of life. In Fiji, before 1995, big was beautiful and bigger was more beautiful—and people really did flatter one another with exclamations about weight gain. In this island paradise, food was not only love, it was a cultural imperative. Eating and overeating were rites of mutual hospitality. Everyone worried about losing weight—but not the way we do. "Going thin" was considered to be a sign of some social problem, a worrisome indication the person wasn't getting enough to eat. (502) The Fijians were, to be sure, a bit 5 drawn by Anne Becker, an anthropologist and psychiatrist who directs obsessed with food; they prescribed research at the Harvard Eating herbs to stimulate the appetite. They were a reverse image of our culture. Disorders Center. She presented her And that turns out to be the point. research at the American Psychiatric Something happened in 1995. A Association last week with all the usual Western mirror was shoved into the caveats. No, you cannot prove a direct face of the Fijians. Television came to causal link0 between television and eatthe island. Suddenly, the girls of rural ing disorders. Heather Locklear" coastal villages were watching the doesn't cause anorexia. Nor does Tori girls of Melrose Place and Beverly Spelling0 cause bulimia. Hills 90210, not to mention Seinfeld Fiji is not just a Fat Paradise Lost. and E.R. It's an economy in transition from Within 38 months, the number of subsistence agriculture" to tourism teenagers at risk for eating disorders and its entry into the global economy more than doubled to 29 percent. The has threatened many old values. number of high school girls who Nevertheless, you don't get a much 10 vomited for weight control went up better lab experiment than this. In just 38 five times to 15 percent. Worse yet, 74 months, and with only one channel, a percent of the Fiji teens in the study television-free culture that defined a said they felt "too big or fat" at least fat person as robust has become a some of the time and 62 percent said television culture that sees robust as, they had dieted in the past month. well, repulsive. This before-and-after television All that and these islanders didn't portrait of a body image takeover was even get Ally McBeal.° GOODMAN / The Culture of Thin Bites Fiji "Going thin" is no longer a social disease but the perceived requirement for getting a good job, nice clothes, and fancy cars. As Becker says carefully, "The acute and constant bombardment of certain images in the media are apparently quite influential in how teens experience their bodies." Speaking of Fiji teenagers in a way that sounds all too familiar, she adds, "We have a set of vulnerable teens consuming television. There's a huge disparity between what they see on television and what they look like themselves—that goes not only to clothing, hairstyles, and skin color, but size of bodies." In short, the sum of Western culture, the big success story of our entertainment industry, is our ability to export insecurity: We can make any woman anywhere feel perfectly rotten about her shape. At this rate, we owe the islanders at least one year of the ample lawyer Camryn ManheinT in The Practice for free. I'm not surprised by research 15 showing that eating disorders are a cultural byproduct. We've watched the female image shrink down to Calista Flockhart at the same time we've seen eating problems grow. But Hollywood hasn't been exactly eager to acknowledge the connection between image and illness. Over the past few weeks since the Columbine High massacre, we've broken through some denial about violence as a teaching tool. It's pretty clear that boys are literally learning how to hate and harm others. Maybe we ought to worry a little more about what girls learn: To hate and harm themselves. 503 SCR ACTGUI AW Calista Flockhart in 1998 causal link: a justified claim Heather Locklear (1961- ): subsistence agriculture: a Camryn Manheim (1961-): that X causes Y. Scientific American actress best model of farming focused on an actress known for playing research based on statistics, known for her television growing enough to keep Ellenor Frutt on The Practice, as is the Becker study that roles, including Amanda one's own family and animals an ABC legal drama that aired Goodman refers to, cannot Woodward in Melrose Place. fed, in contrast to growing from 1997 until 2004. food to sell or large-scale demonstrate causality; instead, it demonstrates Tori Spelling (1973- J.- correlation, a mathematical American actress and link between two (or more) best-selling author. commercial farming. Ally McBeal: an phenomena that is likely not award-winning Fox television chance or accidental in series that aired from 1997 nature. Prolonged exposure to until 2002 and featured direct sunlight is correlated Calista Flockhart—whose with higher rates of skin thin figure was often the cancer, but this fact does not subject of comment—as a mean that playing tennis in young attorney working in Arizona year-round causes Boston. skin cancer. 504 CHAPTER 22 HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU? RESPOND. Chapter 11 notes that causal arguments are often included as part of other arguments. Goodman's article reports on Anne Becker's research (an excerpt of which is reprinted in the following selection, beginning on page 505) to support a larger argument. LINK TO P. 243 1. What is Goodman's argument? How does she build it around Becker's study while not limiting herself to that evidence alone? (Consider, especially, paragraphs 15-17.) 2. What knowledge of popular American culture does Goodman assume that her Boston Globe audience has? How does she use allusions to American TV programs to build her argument? Note, for example, that she sometimes uses such allusions as conversational asides—"All that and these islanders didn't even get Ally McBeal," and "At this rate, we owe the islanders at least one year of the ample lawyer Camryn Manheim in The Practice for free"—to establish her ethos. (For a discussion of ethos, see Chapter 3.) In what other ways do allusions to TV programs contribute to Goodman's argument? Would you have understood this article without the glosses to Ally McBeal and The Practice that the editors have provided? What does this situation teach you about the need to consider your audience and their background knowledge as you write? (See Chapter 6 for a discussion of audience.) 3. At least by implication, if not in fact, Goodman makes a causal argument about the entertainment industry, women's body image, and the consequences of such an image. What sort of causal argument does she set up? (For a discussion of causal arguments, see Chapter 11.) How effective do you find it? Why? A Fijian woman—before 1995 4. Many professors would find Goodman's conversational style inappropriate for most academic writing assignments. Choose several paragraphs of the text that contain information appropriate for an argumentative academic paper. Then write a few well-developed paragraphs on the topic. (Paragraphs 4-8 could be revised in this way, though you would put the information contained in these five paragraphs into only two or three longer paragraphs. Newspaper articles often feature short paragraphs of one or two sentences, which is generally an inappropriate length for paragraphs in academic writing.) ▼ Anne E. Becker receiued her MD and PhD in anthropology as tuell as her ScM in epidemiology from Harvard University. Currently, she is uice-chair of the Department 0/Global Health and Social Medicine, inhere she holds the Maude and Lillian Pressley Professorship; she also serves as an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, ivhere she directs the Social Sciences MD-PhD Program. Throughout her career, Becker has conducted/ieldivork in Fiji on teenage girls and eating disorders, which is sometimes referred to as "disordered eating" in research on this topic. This selection presents three sections of one of Becker's research articles, "Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji," which originally appeared in a special 2004 issue of the academic journal Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry devoted to global eating disorders. The sections presented are "Abstract," "Discussion," and "Conclusions"; if you are familiar with research articles, you can immediately guess that the missing sections are those between the abstract and the discussion section that review earlier research on the topics of the paper, state the research questions to be investigated, describe the methods used to investigate the research questions, and report the results of the study. As you read the sections reprinted here, consider how writing about research for other researchers (as Becker has done here) differs from writing about research for a popular audience (as Ellen Goodman does in the previous selection, "The Culture of Thin Bites Fiji," which relies on an earlier oral presentation of Becker's research as a starting point for Goodman's discussion). Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji: Negotiating Body Image and Identity during Rapid Social Change ANNE E. BECKER ABSTRACT Although the relationship between media exposure and risk behavior among youth is established at a population level, the specific psychological and social mechanisms mediating the adverse effects of media on youth remain poorly understood. This study reports on an investigation of 506 CHAPTER 22 HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU? narrative data ... semi-structured, open-ended interviews: data resulting from oral interviews during which the girls answered questions covering a range of topics and told stories about their experiences rather than simply answering the sorts of questions you find on questionnaires where the ordering of questions is fixed and the choices of answers are given and forced (e.g., Yes/No; Strongly Agree/Agree/Disagree/ Strongly Disagree). disparagement: speaking about in a negative way. the impact of the introduction of television to a rural community in Western Fiji on adolescent ethnic Fijian girls in a setting of rapid social and economic change. Narrative data were collected from 30 purposively selected ethnic Fijian secondary school girls via semi-structured, open-ended interviews. Interviews were conducted in 1998, 3 years after television was first broadcast to this region of Fiji. Narrative data were analyzed for content relating to response to television and mechanisms that mediate self and body image in Fijian adolescents. Data in this sample suggest that media imagery is used in both creative and destructive ways by adolescent Fijian girls to navigate opportunities and conflicts posed by the rapidly changing social environment. Study respondents indicated their explicit modeling of the perceived positive attributes of characters presented in television dramas, but also the beginnings of weight and body shape preoccupation, purging behavior to control weight, and body disparagement. Response to television appeared to be shaped by a desire for competitive social positioning during a period of rapid social transition. Understanding vulnerability to images and values imported with media will be critical to preventing disordered eating and, , . , potentially, other youth risk behaviors in this population, as well as other something populations at risk. KEY WORDS: body image, eating disorders, Fiji, modernization DISCUSSION Minimally, and at the most superficial level, narrative data reflect a shift in fashion among the adolescent ethnic Fijian population studied. A shift in aesthetic ideals is remarkable in and of itself given the numerous social mechanisms that have long supported the preference for large bodies. Moreover, this change reflects a disruption of both apparently stable traditional preference for a robust body shape and the traditional disinterest in reshaping the body (Becker 1995). Subjects' responses to television in this study also reflect a more complicated reshaping of personal and cultural identities inherent in their endeavors to reshape their bodies. Traditionally for Fijians, identity had been fixed not so much in the body as in family, community, and relationships with others, in contrast to Western-cultural models that firmly fix identity in the body/self. Comparatively speaking, social identity is manipulated and projected through personal, visual props in many Western social contexts, whereas this was less true in Fiji. Instead, Fijians have traditionally invested themselves in nurturing others—efforts that are then concretized in the bod- BECKER / Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji ies that one cares for and feeds. Hence, identity is represented (and experienced) individually and collectively through the well-fed bodies of others, not through one's own body (again, comparatively speaking) (Becker 1995). In addition, since Fiji's economy has until recently been based in subsistence agriculture, and since multiple cultural practices encourage distribution of material resources, traditional Fijian identity has also not been represented through the ability to purchase and accumulate material goods. More broadly than interest in body shape, however, the qualitative data demonstrate a rather concrete identification with television characters as role models of successful engagement in Western, consumeristic lifestyles. Admiration and emulation of television characters appears to stem from recognition that traditional channels are ill-equipped to assist Fijian adolescents in navigating the landscape of rapid social change in Fiji. Unfortunately, while affording an opportunity to develop identities syntonic with the shifting social context, the behavioral modeling on Western appearance and customs appears to have undercut traditional cultural resources for identity-making (Becker et al. 2002). Specifically, narrative data reveal here that traditional sources of information about self-presentation and public comportment have been supplanted by captivating and convincing role models depicted in televised programming and commercials. It is noteworthy that the interest in reshaping the body differs in subtle 5 but important ways from the drive for thinness observed in other social contexts. The discourse on reshaping the body is, indeed, quite explicitly and pragmatically focused on competitive social positioning—for both employment opportunities and peer approval. This discourse on weight and body shape is suffused with moral as well as material associations (i.e., that appear to be commentary on the social body). That is, repeatedly expressed sentiment that excessive weight results in laziness and undermines domestic productivity may reflect a concern about how Fijians will "measure up" in the global economy. The juxtaposition of extreme affluence depicted on most television programs against the materially impoverished Fijians associates the nearly uniformly thin bodies and restrained appetites of television characters with the (illusory) promise of economic opportunity and success. Each child's future, as well as the fitness of the social body, seems to be at stake. In this sense, disordered eating among the Fijian schoolgirls in this study appears to be primarily an instrumental means of reshaping body and identity to enhance social and economic opportunities. From this perspective, it may be premature to comment on whether or not disordered eating behaviors share the same meaning as similar behaviors in other cultural contexts. 507 syntonic: emotionally responsive to one's environment. discourse: here, the kinds of comments young girls made about a particular topic during the interviews. 508 CHAPTER 22 nosologic: relating to diseases. HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU? It is also premature to say whether these behaviors correspond well to Western nosologic categories describing eating disorders. Regardless of any differences in psychological significance of the behaviors, however, physiologic risks will be the same. Quite possibly—and this remains to be studied in further detail—disordered eating may also be a symbolic embodiment of the anxiety and conflict the youth experience on the threshold of rapid social BECKER / Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji change in Fiji and during their personal and collective navigation through it. Moreover, there is some preliminary evidence that the disordered eating is accompanied by clinical features associated with the illnesses elsewhere and eating disorders may be emerging in this context. Finally, television has certainly imported more than just images associating appearance with material success; it has arguably enhanced reflexivity about the possibility of reshaping one's body and life trajectory and popularized the notion of competitive social positioning. The impact of imported media in societies undergoing transition on local values has been demonstrated in multiple societies (e.g., Cheung and Chan 1996; Granzberg 1985; Miller 1998; Reis 1998; Tan et al. 1987; Wu 1990). As others have argued in other contexts, ideas from imported media can be used to negotiate "hybrid identities" (Barker 1997) and otherwise incorporated into various strategies for social positioning (Mazzarella 2003) and coping with modernization (Varan 1998). Likewise and ironically, here as elsewhere in the world (see Anderson-Fye 2004), Fijian youth must craft an identity which adopts Western values about productivity and efficiency in the workplace while simultaneously selling their Fijian-ness (an essential asset to their role in the tourist industry). Self-presentation is thus carefully constructed so as to bridge and integrate dual identities. That these identities are not consistently smoothly fused is evidenced in the ambivalence in the narratives about how thin a body is actually ideal. The source of the emerging disordered eating among ethnic Fijian girls thus appears multifactorial and multidetermined. Media images that associate thinness with material success and marketing that promotes the possibility of reshaping the body have supported a perceived nexus between diligence (work on the body), appearance (thinness), and social and material success (material possessions, economic opportunities, and popularity with peers). Fijian self-presentation has absorbed new dimensions related to buying into Western styles of appearance and the ethos of work on the body. A less articulated parallel to admiration for characters, bodies, and lifestyles portrayed on imported television is the demoralizing perception of not comparing favorably as a population. It is as though a mirror was held up to these girls in which they perhaps saw themselves as poor and overweight. The eagerness they express in grooming themselves to be hard workers or perhaps obtain competitive jobs perhaps reflects their collective energy and anxiety about how they, as individuals, and as a Fijian people, are going to fare in a globalizing world. Thus preoccupation with weight loss and the restrictive eating and purging certainly reflect pragmatic strategies to optimize social and economic success. At the same time, they surely contribute 509 reflexivity: self-reflection. Becker uses survey and interview data to support her argument about eating disorders in Fiji. Chapter 4 offers examples of "hard evidence" used in arguments based on fact. LINK TO P. 56 multifactorial and multidetermined: created by many factors and caused by many forces. nexus: a point of convergence or intersection. 510 C H A P T E R 22 HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU1 to body- and self-disparagement and reflect an embodied distress about the uncertainty of personal future and the social body. epidemiologic data: data, likely Epidemiologic data' from other populations confirm an association quantitative, concerning the between social transition (e.g., transnational migration, modernization, cause, spread, and control of urbanization) and disordered eating among vulnerable groups (Andersondiseases. Fye and Becker 2004). In particular, the association between upward mobility and disordered eating across diverse populations has relevance here (Anderson-Fye 2000; Buchan and Gregory 1984; Silber 1986; Soomro et al. 1995; Yates 1989). Exposure to Western media images and ideas may further contribute to disordered eating by first promoting comparisons that result in perceived economic and social disadvantage and then promoting the notion that efforts to reshape the body will enhance social status. It can be argued that girls and young women undergoing social transition may perceive that social status is enhanced by positioning oneself competitively through the informed use of cultural symbols—e.g., by bodily appearance and thinness (Becker and Hamburg 1996). This is comparable to observations that children of immigrants to the U.S. (for whom the usual parental "map of experience" is lacking) substitute alternative "cultural guides" from the media as resources for negotiating successful social strategies (Suarez-Orozco and Suarez-Orozco 2001). In both scenarios, adolescent girls and young women assimilating to new cultural standards encounter a ready cultural script for comportment and appearance in the media. CONCLUSIONS "I've wondered how television is made and how the actress and actors, I always wondered how television, how people acted on it, and I'm kind of wondering whether it's true or not." (S-48) The increased prevalence of disordered eating in ethnic Fijian schoolgirls 10 is not the only story—or even the most important one—that can be pieced together from the respondents' narratives on television and its impact.1 Nor are images and values transmitted through televised media singular forces in the chain of events that has led to an apparent increase in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. The impact of media coupled with other sweeping economic and social change is likely to affect Fijian youth and adults in many ways. On the other hand, this particular story allows a window into the powerful impact and vulnerability of this adolescent female population. This story also allows a frame for exploring resilience and suggesting interventions for future research. BECKER / Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji In some important ways, Fiji is a unique context for investigating the impact of media imagery on adolescents. In Fiji in particular, the evolving and multiple—and potentially overlapping or dissonant—social terrain presents novel challenges and opportunities for adolescents navigating their way in the absence of guidance from "conventional" wisdom and social hierarchies that may have grown obsolete in some respects. Doubtless the profound ways in which adolescent girls are influenced by media imagery extend beyond the borders of Fiji and the ways in which young women in Fiji consume and reflect on televised media may suggest mechanisms for its impact on youth in other social contexts. This study, therefore, allows insight into the ways in which social change intersects with the developmental tasks of adolescence to pose the risk of eating disorders and other youth risk behaviors. Adolescent girls and young women in this and other indigenous, small-scale societies may also be especially vulnerable to the effects of media exposure for several key reasons. For example, in the context of rapid social change, these girls and young women may lack traditional role models for how to successfully maneuver in a shifting economic and political environment. Moreover, in societies in which status is traditionally ascribed rather than achieved," girls and women may feel more compelled to secure their social position through a mastery of self-presentation that draws heavily from imported media. It is a logical and frightening conclusion that vulnerable girls and women across diverse populations who feel marginalized from the locally dominant culture's sources of prestige and status may anchor ascribed status: status that one is granted by others, often on the basis of external qualities (for example, being a firstborn son in a society that values male children and pays attention to birth order). achieved status: status that one Singer-songwriter Jill Scott plays Precious somehow wins or attains (for Ramotswe, owner of the No. I Ladies' Detective example, placing first in a Agency, in the television minise-ries about Alexander McCall Smith's fictional sleuth, set in Botswana. Ramotswe frequently reflects on her status as a "traditionally built" African woman in a society where standards of female attractiveness are rapidly changing. 511 competition). HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU7 their identities in widely recognized cultural symbols of prestige popularized by media-imported ideas, values, and images. Further, these girls and women have no reference for comparison of the televised images to the "realities" they portray and thus to critique and deconstruct the images they see compared with girls and women who are "socialized" into a culture of viewership. Without thoughtful interventions2—yet to be explored with the affected communities—the unfortunate outcome is likely to be continued increasing rates of disordered eating and other youth risk behaviors in vulnerable populations undergoing rapid modernization and social transition. NOTES 1. For example, the increased incidence of suicide and other self-injury in Fiji (Pridmore et al. 1995) may index social distress related to rapid social change. 2. Prevention efforts that might be useful include psychoeducational information about the psychological and medical risks associated with bingeing, purging, and self-starvation as well as media literacy programs that assist youth in critical and informed viewing of televised programming and commercials. REFERENCES Anderson-Fye, E.P. 2000 Self-Reported Eating Attitudes Among High School Girls in Belize: A Quantitative Survey. Unpublished Qualifying Paper. Department of Human Development and Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. Anderson-Fye, E. 2004 A "Coca-Cola" Shape: Cultural Change, Body Image, and Eating Disorders in San Andres, Belize. Culture, Medicine and Society 28: 561-595. Anderson-Fye, E., and A.E. Becker 2004 Socio-Cultural Aspects of Eating Disorders. In Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity. J.K.Thompson, ed., pp. 565-589. Wiley. Barker, C. 1997 Television and the Reflexive Project of the Self: Soaps, Teenage Talk and Hybrid Identities. British Journal of Sociology 48: 611-628. Becker, A.E. 1995 Body, Self, Society: The View from Fiji. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Becker, A.E., and P. Hamburg 1996 Culture, the Media, and Eating Disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 4: 163-167. Becker, A.E., R.A. Burwell, S.E. Gilman, D.B. Herzog, and P. Hamburg 2002 Eating Behaviors and Attitudes Following Prolonged Television Exposure Among Ethnic Fijian Adolescent Girls. British Journal of Psychiatry 180: 509-514. BECKER / Television, Disordered Eating, and Young Women in Fiji Buchan.T, and L.D. Gregory 1984 Anorexia Nervosa in a Black Zimbabwean. British Journal of Psychiatry 145: 326-330. Cheung, C.K., and C.F. Chan 1996 Television Viewing and Mean World Value in Hong Kong's Adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality 24: 351-364. Granzberg, G. 1985 Television and Self-Concept Formation in Developing Areas. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 16: 313-328. Mazzarella, W. 2003 Shoveling Smoke: Advertising and Globalization in Contemporary India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Miller, C.J. 1998 The Social Impacts of Televised Media Among the Yucatec Maya. Human Organization 57: 307-314. Pridmore, S., K. Ryan, and L. Blizzard 1995 Victims of Violence in Fiji. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 29:666-670. Reis, R. 1998 The Impact of Television Viewing in the Brazilian Amazon. Human Organization 57: 300-306. Silber.T.J. 1986 Anorexia Nervosa in Blacks and Hispanics. International Journal of Eating Disorders 5:121-128. Soomro, G.M., A.H. Crisp, D. Lynch, D.TVan, and N. Joughin 1995 Anorexia Nervosa in "Non-White" Populations. British Journal of Psychiatry 167: 385-389. Suarez-Orozco, C, and M.M. Suarez-Orozco 2001 Children of Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Tan, A.S., G.K. Tan, and A.S. Tbn 1987 American TV in the Philippines: A Test of Cultural Impact. Journalism Quarterly 64:65-72,144. Varan, D. 1998 The Cultural Erosion Metaphor and the TTanscultural Impact of Media Systems. Journal of Communication 48: 58-85. Wu,Y.K. 1990 Television and the Value Systems of Taiwan's Adolescents: A Cultivation Analysis. Dissertation Abstracts International 50: 3783A. Yates, A. 1989 Current Perspectives on the Eating Disorders: I. History, Psychological and Biological Aspects. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 28(6): 813-828. (513 CHAPTER 22 HOW DOES POPULAR CULTURE STEREOTYPE YOU7 RESPOND* 1. How does Becker link exposure to Western media to the changing notions young Fijian women have of their own bodies? Why does Becker claim these women now want to be thin? How are these changes linked to other social changes occurring in Fiji, to adolescence, and to gender, especially in small-scale societies? 2. As Becker notes, she relies on qualitative data—specifically, interview data—to support her arguments. Why are such data especially appropriate, given her goals of understanding the changing social meanings of body image for young Fijian women as part of other rapid social changes taking place in Fiji? (For a discussion of firsthand evidence, see Chapter 17.) 3. Throughout the "Discussion" and "Conclusions" sections, Becker repeatedly qualifies her arguments to discourage readers from extending them further than she believes her data warrant. Find two cases where she does so, and explain the specific ways that she reminds readers of the limits of her claims. (For a discussion on qualifying claims and arguments, see Chapter 7.) 4. These excerpts from Becker's article represent research writing for an academic audience. What functions does each of the reprinted sections serve for the article's readers, and why is each located where it is? Why, for example, is an abstract placed at the beginning of an article? Why are key words a valuable part of an abstract? 5. In paragraph 3, in the "Discussion" section of her article, Becker compares and contrasts how Westerners (which would include Americans) and Fijians understand identity, especially as it relates to the body. Write an essay in which you evaluate Becker's characterization of Western notions of identity. (For a discussion of evaluative arguments, see Chapter 10.) Unless you have detailed knowledge of a culture very different from Western cultures (Fiji, for example), you may want to begin by trying to demonstrate that Becker's assessment is correct, at least to some degree, rather than claiming that she misunderstands the West. Once you've conceded that there's at least some truth in her assessment, you may be able to cite cases of American subcultures that don't "firmly fix identity in the body/self."