JUST HOW BAD IS WETLAND DEGRADATION? Daily monitor

advertisement

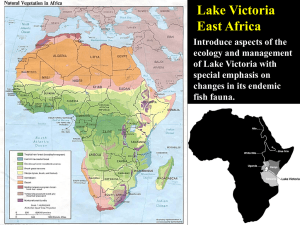

JUST HOW BAD IS WETLAND DEGRADATION? Daily monitor Thursday, March 12 2015: By Joseph Kato In Summary While there has been a lot of talk about the need to conserve our wetlands, Murchison Bay in Kampala is one example that action should follow the talk In Murchison Bay in Muyenga-Bukasa, Kampala District, Lake Victoria and the Luzira wetland seem to have merged, as the lake flows about 500 metres into the swamp. Green vegetation, including yams and sugar canes float on the water, and in some places, a green layer floats on the water. There are also permanent structures in the wetland. With weather experts predicting that the rainy season is upon us, residents are worried about the reverse flow of water in Lake Victoria, and how it will affect them. Edward Abigaba, a boda boda rider, who has lived for more than 15 years in the area, expressed dismay at the state of affairs. “It is unfortunate that people have encroached on the wetland,” he said, adding that “if water has intruded the wetland in a dry season, what will happen when the heavy rains start? I request the concerned authorities to do the needful before floods kill us.” The residents said water began encroaching on the wetland mid last year. They place the blame on people digging terraces to channel water for agriculture activities. The residents also criticise the National Environment Management Authority (Nema) which has failed to implement laws that impede those constructing in wetlands. Residents’ take Manisuli Kalule, whose house is close to NEMA’s border line, believes the flooding of the wetland is a result of a slope that has been created by rubbish from Nakivubo channel. “The papyrus which could have blocked the water from encroaching has been cut for agriculture. So, the collected heaps of rubbish have caused the water to change course. I ask the government to find a place where they can channel off the water that flows from the Nakivubo channel,” he says. Getrude Naluggwa a 73-year-old and a resident of the area since 1974 believes human encroachment on the wetland are to blame. Naluggwa who I met in a potato garden near the wetland puts the blame on the authorities who have not implemented the laws which protect the wetlands. “Even leaders have not protected the environment. I wonder how this man [pointing to a house] constructed in the middle of the wetland and no one blames him,” she says. What has caused it In 2013, Dr Tom Okurut, the executive director of NEMA, presented a paper on the fate of Lake Victoria. In the paper, he predicted that the lake would dry up due to human activities such as overfishing, pollution, conversion of forests and wetlands into farmland that remove the vegetation cover from soil, resulting in massive silting. Dr Okurut pointed out that Lake Victoria is under intense pollution from the cities of Kampala, Kisumu and Mwanza since it is the critical source of water to the unplanned urbanisation. For instance, Kampala’s more than two million people get water from Murchison Bay, also referred to as the mouth of the lake. Dr Okurut further pointed out that since Nakivubo swamp used to trap impurities like sewage, this is no longer possible since it was degraded. What happens now is that these impurities, make their way into Murchison Bay, polluting it. Another highlight of the paper is the fact that there is no clear regulation of the lake. Whoever is next to the lake regulates it as they see fit. Steven Sande, chairperson Luzira Port Bell Beach Management, concurs that the universal ownership of the lake has led to illegal fishing methods being used. “Whenever we try to implement the laws against illegal fishing, the culprits threaten to harm us. Some of them have friends and relatives in the Marine Force. We have decided to remain silent because politics is killing the fishing industry,” he says. In addition, factors of pollution include; lack of knowledge on managing the environment, poor urban plans, poor compliance culture, poor policies and systems, lack of research and poor coordination among government agencies. What could happen if Lake Victoria water levels drop? In case Lake Victoria’s water levels drop, Uganda’s hydro-electric power will be severely affected. For instance, according to the paper Dr Okurut presented power dams at Nalubaale and Kiira will eventually cease since electricity is produced using water from the lake. Even the potential power production along the Nile, including Kalagala and Murchison Falls, estimated at 3,000MW, will disappear with Lake Victoria. Okurut believes the disease burden on Ugandans is likely to increase if the degradation is not checked. For long, according to Okurut, fish was the cheapest source of proteins, but now prices are increasing as local consumers have to compete with the export markets. Diseases such as cholera, bilharzia and malaria are increasing, especially where the water has become polluted. In addition to this, conflicts over resources such as fishing grounds, wetlands and forests across the country are likely to increase. Wetland policy Uganda adopted a wetland policy in July 1994 establishing a number of agencies purposely to safeguard swamps. But the designated authorities seem to have failed to enforce the rules. The Constitution says the government should hold wetlands and other natural resource in trust for all citizens. In 2010, when floods hit most suburbs of Kampala, members of the Natural Resources Committee of Parliament toured wetlands in Kampala, Wakiso and Mukono districts. The group accused then Kampala City Council (currently Kampala Capital City Authority) and Uganda Land Commission (ULC) of issuing illegal land titles. They also charged that Uganda Investment Authority (UIA) and National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) have improperly issued operational permits for the wetlands. Patrick Turyatunga, the environment officer at A ROCHA-Uganda, an NGO that focuses on the environment, said the wetland has dropped to 285 hectares from 498 in just five years. “If no quick solutions are found the wetland would be no more by this year.” Still in 2010, some critics said the government is a part of the problem. For instance, Frank Muramuzi, the executive director of National Association of Professional Environmentalist (NAPE) noted that degradation of wetlands is by the government itself. “It is either [by people who] are working for government, a project supported by government or government officials involved in wetland degradation like construction of factories.” Experts also warn that reduced wetlands have less capacity to store water and filter nutrients and pollutants. As a result, filth has collected where water from Kampala pours into Lake Victoria. Pollution hotspots on the lake include Murchison Bay and Kitubulu in Uganda, Bukoba and Mwanza in Tanzania, Musoma and Kisumu in Kenya. In April 2012, Jackson Kitamirike, a water expert in the Ministry of Water and Environment checked waters of Murchison Bay and realised there is increasing contamination with the filth that flows into the water. “The water is dark and smelly which shows that something has gone amiss. He pointed out factors like dumping human waste, blood and cow dung from slaughterhouse and encroachment on wetland as key contributors to the decline of the lake. In 2004, Kitamirike said the depth of the lake at Murchison Bay was seven metres, but in 2012 it had dropped to only one-and-half metres. This meant the lake is dropping at a rate of one metre every year. He attributed this to uncollected waste and soils washed into the lake during the rainy season. As a result, the waste and soil are piling up and reducing the depth of the lake. Experts take Samuel Apedel, the spokesperson of National Water and Sewage Corporation (NWSC) said NWSC is concerned about the state of the lake and as a result they are constructing a sewage plant to treat water from Nakivubo channel before it reaches the lake. “Although I am not sure of what is happening at Murchison bay, I suspect the encroachment results from dirt and rubbish which goes to the lake whenever it rains. We know that water is polluted and pushes the cost of treatment and supply of water. The plant will help us to supply 340 million litres of water per day. Besides, it will help us to produce electricity which will be operating the plant.” Engineer Aaron Kabirizi, the director of Water Development at the ministry of Water and Environment says the change in the flow of water usually results from the increase of the amount of water in the water body. “I think the right people to handle this issue are the director of environment or water resources. However, what I know is that water usually diverts to a nearby places when the levels go high,” Mr Kabirizi says. Isaac Banada, environmental analyst of Uganda Environment Protection Forum (UEPF) says, the change of colour is a sign of pollution, which aids growth of aquatic plants such as algae. Banada warns that if the designated water and wetland bodies do not do the necessary in time, water may soon start stinking. “This might lead to the outbreak of epidemics like cholera and typhoid since locals in that place draw from wetlands,” he says. Carol Kizibaziba, an environmentalist with NAPE says, reverse flow of water usually happens due to infilling of wetlands, streams and rivers. “Silting of the rivers, streams, wetland or the lake itself can result into water encroaching on the nearby places,” she adds. Other factors capable of antagonising the flow of water according to Kizibaziba among others include destruction of water catchment such as forests surrounding the lake and drainage channels in forests. Kizibaziba says, it is time the ministry of Water and Environment, and NEMA woke up and implemented penalties outlined in section 68 of the 1995 National Environment Statute (NES) to save wetlands and all other water sources. What NES says Section 68 of the 1995 National Environment Statute states that people should be prevented from taking any action which would or is reasonably likely to do harm to the environment. Compensation should be awarded to people whose environment or livelihood has been harmed by the action of the offender. In addition, the accused should financially facilitate an authorised person or organisation to restore the destroyed environment to its state.