The Story of Robert Bruce Pt1

advertisement

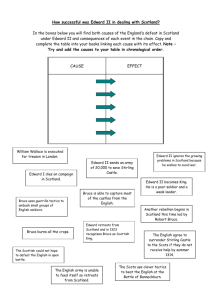

The Story of Robert Bruce Overview In 1306 Robert Bruce made himself King of Scots but immediately found himself opposed on many sides. Not only did the English King Edward I wish to defeat him, but his Scottish enemies included the powerful families of Balliol and Comyn. For a period of time Bruce was driven out of Scotland but would return to carry out a highly successful campaign against his Scottish enemies and the English presence in Scotland. This campaign would include the dramatic and historic victory at Bannockburn in 1314. With such a success came the reputation as one of Scotland’s finest kings. Yet the story of Robert Bruce is a more complicated one than that say, of William Wallace. Part I of Bruce’s story will investigate his actions leading up to Bannockburn as you begin to consider whether Bruce deserves his considerable reputation. Who were the Bruces? The Bruce family originated from France. They arrived in England in 1066 when William, Duke of Normandy successfully invaded English and took the throne after the Battle of Hastings. The Bruce family received land in England by William and later land in Scotland by the Scottish King David I in the early 12th Century. Most of the Scottish lands were in the south-west, particularly around Annan and Lochmaben. The Bruces considered themselves as Scottish royalty. One of their members had married Princess Isabella, the great granddaughter of King David I. Remember that there was a Robert Bruce who competed for the throne after the death of the Maid of Norway. He had even argued that Alexander II had promised him the throne before he had a son who would become Alexander III. In 1295 Robert Bruce (the Competitor) had died. It was his son, the defender of Carlisle who had asked for the Scottish throne after Edward’s successful invasion in 1296, to which Edward reputedly replied: ‘Have we nothing to do, but to conquer kingdoms for you?’ 1|Page It was left to the third generation Robert Bruce to pursue the family claim to the throne of Scotland. David I Henry of Northumberland David, Earl of Huntingdon Isabella Robert Bruce (the Competitor) Robert Bruce (the defender of Carlisle) Robert Bruce Bruce’s Changing Allegiances One of the remarkable facts about the future King of Scotland was the number of times that he changed sides during the war against English rule. His dilemma was that there was little chance of him becoming king whilst the English ruled Scotland. However, if he went against Edward it was possible that the family would lose their lands and also their lives. Until 1296, the year of Edward’s invasion, Bruce stayed loyal to Edward I. However, in 1297 Bruce decided to join forces with the Scottish rebels and took part in attacks on Irvine. Therefore, at the time of Wallace’s battles against the English, the younger Bruce was supporting Wallace’s cause. His father remained loyal to Edward in order to safeguard their lands in England. In 1298, following Wallace’s defeat at Falkirk, Bruce became Joint Guardian with his old rival John Comyn. Both Comyn and his uncle, John Balliol had their own claims on the throne, of course, and Bruce soon fell out with Comyn and resigned as Guardian. He continued to support the Scots until making peace with Edward in 1302. It must have suited Bruce to do this at this time. It looked as if Edward was almost ready to regain complete control of Scotland. Plus there had been rumours of a return to Scotland for John Balliol, something Bruce was keen to avoid. He remained loyal for two years before beginning to question whether he had been sufficiently rewarded by Edward for his support. From 1304-06 Bruce was heavily involved in plots to free Scotland. 2|Page A Killing and a Crown Bruce’s father died in 1304, making him now Earl of Annandale and Carrick. Perhaps this new power or the fact that the English King Edward was now an old man (67) gave reason for Bruce to be optimistic about his chances for adding to his power. Bruce began to enter into discussions with other important Scots to become King of Scotland. He gained the support of the Bishop of St Andrews – William Lamberton. He also met again with John Comyn to discuss their rival claims. Initially it appeared that this first meeting went well. Comyn appeared to accept that Bruce would be King in return for Bruce’s Scottish lands being handed over to the Comyn family. It is possible, however, that Comyn still had his own ambitions to be King and may have leaked Bruce’s plan to none other than Edward I. Edward was furious and ordered Bruce’s immediate arrest, forcing him to flee back to the southwest. It was in Dumfries that the second meeting between Comyn and Bruce took place. A church was chosen as the location for the meeting as fighting between these old rivals was forbidden. The 10th February 1306 saw the men meet at Greyfriars Monastery in Dumfries. Bruce arrived with his supporters Kirkpatrick and Seaton. Comyn was accompanied by one of his uncles. Historians will never know exactly what was said in this meeting or how the violence began. We do know that the events in the church would force Bruce’s hand in taking control of Scotland. It can be assumed that Bruce and Comyn argued. Perhaps Bruce accused Comyn of betraying him to Edward. During the struggle that followed, it appears that Bruce pulled a dagger and stabbed Comyn in front of the high altar. When Bruce left the church and told his companions what he had done Kirkpatrick is reputed to have said in response ‘I’ll mak siccar’ (I will make sure). It is likely that Kirkpatrick then executed Comyn and his uncle. 3|Page These murders were an incredible serious event. Not only had one of the most important and powerful Scottish nobles been put to death, but the murders had taken place in the sacred surroundings of a church. Bruce would face opposition from other Scottish lords and could face possible excommunication from the Catholic Church. A stark choice faced Bruce – go on the run as an outlaw or take this chance to proclaim himself King. Bruce decided to gamble on the latter. With his supporters alongside, he rode out to the Royal Castle in Dumfries (Castledykes) and took back control from English hands. It was here that Bruce first proclaimed himself King of Scotland. The Coronation of Robert Bruce Bruce’s only hope of avoiding too much Scottish opposition and the threat of excommunication was to quickly gather enough support for his claim to the throne. He had already gained the support of Lamberton and this was was followed by support from the Bishop of Glasgow, Robert Wishart. Next Bruce made sure that he controlled all the main castles in the south-west, including Dumfries, Lochmaben, Annan and Kirkcudbright. The next step for Bruce was to head north to Perth and Scone. It was important that a formal ceremony take place so other Scots could begin to regard him as their ruler. In two separate events, on March 25th and 27th Bruce was crowned. The most ‘official’ ceremony was on the 27th, despite the absence of the Scottish coronation robes, crown and the Stone of Destiny. You will remember that these had been taken by Edward’s men ten years before. This was a much smaller ceremony than would normally accompany a Scottish coronation. In attendance were some of Bruce’s brothers, three of Scotland’s leading bishops and a number of important nobles including Lennox and Sir James Douglas. The Earl of Fife traditionally crowned Scottish Kings but as the Earl was a child currently living under English control, the task fell to the Earl’s sister Isabel, Countess of Buchan. 4|Page In the hastily arranged ceremony the royal robes were replaced by a bishop’s cloak. The ‘crown’ was a golden collar, donated by the Countess. All these issues did not take away from the fact that Bruce had now officially been crowned King. His next challenge was to strengthen his control of other parts of Scotland and deal with enemies, both at home and in England. Early Defeats Such challenges would prove considerable. Most of the key Scottish castles were under English control. The Comyn family and their allies, for example the MacDougalls of Argyll were eager on revenge on Bruce. Many Scots had been horrified at the actions of Bruce in killing Comyn, particularly in the manner in which the murder had taken place. Historian Fiona Watson summed up the situation Bruce faced in 1306: ‘A large number of Scots saw it as their duty to fight against Bruce. In the years after 1306 most Scots preferred to live under the rule of an English King rather than accept a man who had seized the throne and murdered a rival in church for it.’ On hearing news of Bruce’s actions, Edward appointed de Valence his commander in Scotland with the order that: ‘All those who were present at the death of John Comyn are to drawn and hanged. All those who agreed to it or helped them afterwards have to meet the same fate. All those captured bearing arms against the King [Edward] are to be hanged or beheaded.’ Despite all these obstacles, Bruce decided to go on the offensive, attempting to unsettle his Scottish enemies. His opposition was strengthened, however, with the arrival of a large English army led by de Valence. Supported by troops from the Comyns and MacDougalls, Bruce’s supporters began to struggle. Bishops Lamberton and Wishart were captured and imprisoned. 5|Page Bruce’s small army came up against a significantly larger force at the Battle of Methven, just outside Perth on 19th June 1306, and was badly defeated. Bruce managed to escape unhurt but many of his commanders were killed or captured. His brother Nigel was soon captured and hanged. His wife and daughter were imprisoned in an English nunnery. The punishment for other supporters of Bruce was even more imaginative. Both the Countess of Buchan and Bruce’s sister, Mary were imprisoned in cages outside Berwick and Roxburgh Castle respectively. Bruce fled the Scottish mainland. After a few short months, it looked as if his ‘reign’ was already over. Bruce Fights Back A well-known legend is often repeated from Bruce’s time spent away from Scotland from 1306-7. It is said that whilst hiding on an island off the coast of Ireland, Bruce watched closely the determination of a spider spinning its web. Taking heart from the spider’s continued efforts until the web was complete, Bruce apparently resolved to keep on fighting until Scotland had regained her independence. Although this story is almost certainly not true, it is clear that from 1307 onwards, events and circumstances began to give Bruce’s supporters some hope for the future. In February 1307 Bruce landed back on the mainland with a small band of supporters. This landing was at Turnberry on the Ayrshire coast. His brothers Alexander and Thomas had arrived with supporters on the Galloway coast but had been captured and executed. Using ‘guerrilla’ or ‘hit and run’ tactics, Bruce fairly quickly established a new army, an army that could move very quickly. The countryside lent itself to this style of ambush strategy, Bruce’s men launching surprise attacks, then quickly disappearing back into the dense woodland. At the Battle of Loudon Hill, on 10th May 1307, Bruce unexpectedly defeated a larger English force, using the soft marshy ground to his advantage, ground that did not suit the English knights. 6|Page An event of huge significance to Bruce’s chances of success took place on July 7th with the death of Edward I. His death coincided with his march on Scotland to oversee the crushing of this latest rebellion. Reaching no further than Burgh-onsands in Cumbria, it is said that as Edward I lay dying he asked for his heart to be taken to the Holy Land and for the flesh to be boiled from his body so his bones could lead the English army in battle against the Scots. Neither request was carried out. Edward’s death was such a boost to Bruce’s chances when the character of the new English king, Edward II is considered. Edward II was neither an able soldier nor a particularly strong leader. He made the decision to postpone his army’s march northwards and returned to London. In struggling to deal with problems in England, Edward’s reluctance to focus on defeating the Scottish rebels gave Bruce the opportunity to steadily gain support and ground across important areas of Scotland’s heartland. Bruce’s Recovery Continues 1308-1314 In 1308 Bruce moved against his Scottish enemies, defeating the pro-English Earl of Buchan and destroying much of the Comyn family’s control in north-east Scotland. In the Battle of the Pass of Brander Bruce defeated his old enemies, the MacDougalls. As a result of such successes, many more noble families began to switch their allegiance to Bruce. March 1309 saw Bruce hold a parliament in St Andrews, which formally recognised him as King. Edward II briefly attempted an invasion in 1310 but the English forces were quickly driven back. Bruce retaliated by invading northern England. Historian Paterson wrote that: ‘Life in Northern England became so bad that normal life could only continue with the permission of the Scots’ By the end of 1310 Bruce controlled all the land north of the River Tay. Over the course of the next few years, his control spread and key castles including those at Perth, Dumbarton, Roxburgh and Linlithgow were retaken from the control of the 7|Page English. Some of the techniques for taking these castles were innovative, including stories of men smuggled in hay carts, or cloaked soldiers stealing up to castle walls in darkness, using cattle as cover. Edinburgh Castle was retaken in March 1314 after a secret path into the castle was used by one of Bruce’s young commanders, Thomas Randolph. By the summer of 1314 only the castles of Berwick, Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control. If Edward II was to re-establish control of Scotland, Stirling played the key role. Its central location would provide the stepping stone for turning back the clock on all of Bruce’s recent successes. Bruce’s brother Edward had laid siege to Stirling Castle for months but the English troops were managing to hold out. Eventually Edward Bruce made an agreement with the castle governor that if an English army had not arrived by midsummer, the castle would be surrendered to the Scots. By early summer Edward had put together one of the biggest armies ever seen on British soil. This battle would play a crucial role in the future of Scotland. Both sides would meet on the field of Bannockburn on June 23rd 1314. 8|Page