Appendix A. Search terms Psychological Harms Search terms

advertisement

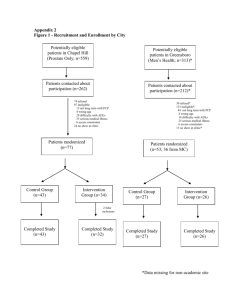

Appendix A. Search terms Psychological Harms Prostate Cancer Lung Cancer Search terms (Medline) Prostate cancer*[tw] OR prostatic cancer*[tw] OR Prostatic Neoplasms[Mesh] OR prostate specific antigen[tw] OR PSA[tw]) AND (screening*[tw] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR early detection[tw] OR biops*[tw] OR surveillance[tw] OR watchful waiting[tw]) AND (depress*[tw] OR distress[tw] OR stress*[tw] OR worry[tw] OR fear*[tw] OR anxiet*[tw] OR quality of life[tw] OR mental health[tw] OR mental disorders[tw] OR psycholog*[tw] OR psychosocial[tw] OR well being[tw] OR uncertainty[tw] OR emotion*[tw] OR false positive*[tw] OR harm*[tw] OR adverse effect*[tw] OR complication*[tw]) (Lung cancer*[tw] OR Lung Neoplasms[Mesh]) AND (screening*[tw] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR early detection[tw] OR biops*[tw] OR surveillance[tw] OR watchful waiting[tw]) AND (depress*[tw] OR distress[tw] OR stress*[tw] OR worry[tw] OR fear*[tw] OR anxiet*[tw] OR quality of life[tw] OR mental health[tw] OR mental disorders[tw] OR psycholog*[tw] OR psychosocial[tw] OR wellbeing[tw] OR well-being[tw] OR uncertainty[tw] OR emotion*[tw] OR false positive*[tw] OR harm*[tw] OR adverse effect*[tw] OR complication*[tw]) Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (Abdominal aortic aneurysm[tw] OR Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal[Mesh]) AND (screening*[tw] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR early detection[tw] OR biops*[tw] OR surveillance[tw] OR watchful waiting[tw]) AND (depress*[tw] OR distress[tw] OR stress*[tw] OR worry[tw] OR fear*[tw] OR anxiet*[tw] OR quality of life[tw] OR mental health[tw] OR mental disorders[tw] OR psycholog*[tw] OR psychosocial[tw] OR well being[tw] OR uncertainty[tw] OR false positive*[tw] OR emotion*[tw] OR harm*[tw] OR adverse effect*[tw] OR complication*[tw]) Osteoporosis ((osteoporosis[tw] OR osteopenia[tw] OR bone density[tw] OR bone mineral density[tw]) AND (screen*[tw] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR early detection[tw] OR densitometry[tw]OR absorptiometry[tw] OR DEXA[tw] OR DXA[tw]) AND (depress*[tw] OR stress*[tw] OR distress [tw] OR worry[tw] OR fear*[tw] OR anxiet*[tw] OR quality of life[tw] OR mental health[tw] OR mental disorders[tw] OR psycholog*[tw] OR well being[tw] OR psychosocial[tw] OR uncertainty[tw] OR emotion*[tw])) NOT (animals NOT humans) (Carotid artery stenos*[tw] OR carotid stenos*[tw] OR Carotid Stenosis[Mesh]) AND (screening*[tw] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR early detection[tw] OR biops*[tw] OR surveillance[tw] OR watchful waiting[tw]) AND (depress*[tw] OR distress[tw] OR stress*[tw] OR worry[tw] OR fear*[tw] OR anxiet*[tw] OR quality of life[tw] OR mental health[tw] OR mental disorders[tw] OR psycholog*[tw] OR psychosocial[tw] OR well being[tw] OR uncertainty[tw] OR false positive*[tw] OR emotion*[tw] OR harm*[tw] OR adverse effect*[tw] OR complication*[tw]) Carotid Artery Stenosis Overdiagnosis Prostate Cancer Search terms (Medline) (“Prostatic neoplasms”[Mesh] OR “prostate cancer”[tw]) AND (screening[tw] OR mass screening[Mesh] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR prostate specific antigen[tw]) OR PSA [tw] AND (overdiagnos*[tw] OR over-diagnos*[tw] OR overdetect*[tw] OR over-detect*[tw]) Lung Cancer (Lung cancer*[tw] OR Lung Neoplasms[Mesh]) AND (screening[tw] OR mass screening[Mesh] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR prostate specific antigen[tw] OR PSA [tw] OR biops*[tw]) AND (overdiagnos*[tw] OR over diagnos*[tw] OR overdetect*[tw] OR over detect*[tw] OR insignifican*[tw]) AND (rate[tw] OR frequency[tw] OR incidence[tw] OR prevalence[tw] OR epidemiology[subheading]) Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (Abdominal aortic aneurysm[tw] OR Aortic Aneurysm, Abdominal[Mesh]) AND (screening[tw] OR mass screening[Mesh] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR biops*[tw]) AND (overdiagnos*[tw] OR over diagnos*[tw] OR overdetect*[tw] OR over detect*[tw] OR insignifican*[tw]) AND (rate[tw] OR frequency[tw] OR incidence[tw] OR prevalence[tw] OR epidemiology[subheading]) Osteoporosis (osteoporosis [MeSH] OR osteoporosis[tw] OR osteopenia[tw]) AND (overdiagnos*[tw] OR over diagnos*[tw] OR overdetect*[tw] OR over detect*[tw] OR diagnostic errors[mesh] OR misdiagnos*[tw] OR misinterpret*[tw]) AND (rate[tw] OR frequency[tw] OR incidence[tw] OR prevalence[tw] OR epidemiology[subheading]) (Carotid artery stenos*[tw] OR carotid stenos*[tw] OR Carotid Stenosis[Mesh]) AND (screening[tw] OR mass screening[Mesh] OR early diagnosis[tw] OR biops*[tw]) AND (overdiagnos*[tw] OR over diagnos*[tw] OR overdetect*[tw] OR over detect*[tw] OR insignifican*[tw]) AND (rate[tw] OR frequency[tw] OR incidence[tw] OR prevalence[tw] OR epidemiology[subheading]) Carotid Artery Stenosis Appendix B. Selected screening services and USPSTF recommendations Screening Service (Year of Most Recent USPSTF Review) Prostate Cancer (2011) USPSTF Recommendations Lung Cancer (2013) B: Recommends annual screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) in persons at high risk for lung cancer based on age and smoking history. B: Recommends one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) by ultrasonography in men aged 65 to 75 who have ever smoked. C: No recommendation for or against screening in men aged 65-75 who have never smoked. D: Recommends against screening in women B: Recommends screening for osteoporosis in women aged 65 years or older and in younger women whose fracture risk is equal to or greater than that of a 65-year-old white woman who has no additional risk factors. I: Insufficient evidence to assess screening in men. D: Recommends against screening for carotid artery stenosis in the general adult population. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (2014) Osteoporosis (2010) Carotid Artery Stenosis (2014)* *Draft evidence report D: Recommends against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer. Appendix C. Study characteristics for 5 screening services Psychological Harms of Prostate Cancer Screening Study Type Outcomes of Interest (Instrument or Data Source) Comparisona (Time Points) Frequency/ Burdenb Qualitative Men’s reactions to an equivocal PSA result (Interviews) Anxiety, depression, & cancerrelated distress (HADS; IES) Anxiety, depression, and HRQoL (HADS; SF-36) Anxiety (items on study-specific questionnaire) Men’s experiences before, during, & after biopsy (Interviews) HRQoL; anxiety (SF-36; STAI) None Burden Change over time (day of screening; 4-6 weeks later) Change over time (before screening and before biopsy) Change over time (before PSA results; awaiting biopsy) None Both Cormier et al., 20026 7 men aged 50-69 years, from a general practice 57 men aged 40-73 years, from families with history of PrCa 569 men aged 50–69 years, recruited for ProtecT 1,781 men aged ≥50 years, enrolled in ERSPC 50 men aged 52-75 years, recruited from urologists, general practitioners & support groups 220 brothers or sons of men with PrCa Both Evans et al., 20077 Macefield et al., 2010c 8 28 men aged 40-75 years, from 6 Welsh general practices 330 men aged 50-69 years, participating in ProtecT Qualitative Longitudinal Men’s responses to screening process (Interviews) Distress (POMS-SF; IES) Change over time (before PSA test; before results; after normal result) None Both Macefield et al., 20099 Medd et al., 200510 4,198 men aged 50–69 years, recruited for ProtecT 31 men, aged 47-91 years, referred to biopsy clinic Longitudinal Anxiety (HADS) Crosssectional/ qualitative Oliffe, 2004d 14 men aged 46-74 years, recruited from support groups or advertising 136 men, mean age 58.5 years, registered for free screening at 2 hospital-based sites Qualitative Men’s experiences before, during, & after biopsy (Studyspecific questionnaire and interviews) Experiences of testing, work-up and diagnosis (Interviews) Avoidant or intrusive cancerrelated thoughts (IES; MHI-5) Change over time (PSA screening; during clinic visit for biopsy; after receiving normal biopsy result; 12 weeks after negative result) Change over time (PSA test; time of biopsy) None None Burden Change over time (before screening; 1 week after normal result) Both Source Subjects Screening Test/Workup Archer and Hayter, 20061 Bratt et al., 20032 Brindle et al., 20063 Carlsson et al., 20074 Chapple et al., 20075 Taylor et al., 200212 11 False-Positive Results Longitudinal Longitudinal Longitudinal Qualitative Longitudinal Longitudinal Both Both Burden Burden Burden Both Fowler et al., 200613 285 men, mean age 61 years, from 3 hospital primary practices Longitudinal PrCA-related thoughts and worry (Study-specific questionnaire) Change over time (6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year after normal PSA test or normal biopsy) Both Ishihara et al., 2006c 14 141 men aged ≥50 years, enrolled from hospital outpatient list Longitudinal HRQoL (SF-36) Burden Katz et al., 200715 210 men, aged 52-70 years, from university hospitals and primary care practices Crosssectional McGovern et al., 200416 16 men, aged 55-74 years, enrolled in the PLCO Qualitative Anxiety; HRQoL; PrCa-related worry and perceived susceptibility (SF-36; SAI-6; study-specific items) Responses to a false-positive screening test (Focus groups) Age- and gender-adjusted SF-36 Japanese national norms, plus change over time within subjects (before biopsy; after results) Primary care patients with PSA findings in the reference range None Burden McNaughtonCollins et al., 200417 Perczek et al., 2002c 18 400 men, mean age 60 years, from 3 hospital primary care practices Crosssectional PrCA-related thoughts and worry (Study-specific questionnaire) Primary care patients with PSA findings in the reference range Both 101 men, mean age 66.7 years, at VA Medical Centers Longitudinal Distress (POMS) Change over time (before & after biopsy) Burden Change over time (6-months intervals, up to 5 years after diagnosis) None Burden Age-matched controls attending urology clinic but w/o PrCa dx Age-matched population controls Burden Age-standardized suicide rate in the general population Scores were compared to published criteria for “caseness” Frequency Normative HADS data from a large non-clinical sample Both Burden Diagnosis (Labeling) Arredondo et al., 200419 383 men, largely >55 years old, enrolled in CaPSURE Longitudinal HRQoL during WW (RAND SF36) Bailey et al., 200720 10 men, aged 64-88 years, attending urology clinic at a tertiary care medical center 60 men awaiting treatment & 21 controls; aged 49-74 years 72,613 men with PrCa (mean age at study entry 71.1 years) and 217,839 age-matched men without PrCa 128 suicides among 77,439 men with PrCa 88 men aged 48-78 years, attending a joint urology/oncology clinic 100 men (mean age 67.1 years) from outpatient clinics Qualitative Uncertainty during WW (Interviews) Crosssectional Longitudinal PrCA-specific QoL (FACT-P validation study) Psychiatric hospitalization; outpatient visits; use of antidepressant medication (Swedish registry data) Suicide (Swedish registry data) Batista-Miranda et al., 200321 Bill-Axelson et al., 201122 Bill-Axelson et al., 201023 Bisson et al., 200224 Burnet et al., 200725 Longitudinal Crosssectional Crosssectional Depression; anxiety; distress; QoL (GHQ30; HADS; IES; EORTC-QOL-30) Anxiety & depression during AS (HADS) Burden Frequency Frequency Daubenmeier et al., 200626 93 men (mean age intervention group 64.8 years, controls 66.5 years) enrolled in RCT on effects of lifestyle changes on PrCa progression 10 men, aged >55 years, from urology/endocrinology clinics 136 suicides among 168,584 men with PrCa (mean age at diagnosis 73.4 years), out of 4,305,358 men followed 1961-2004 148 suicides among 342,497 men (mean age at diagnosis 70.2 years) with PrCa 27 men, aged 65-88 years at study entry, with localized disease, recruited for RCT comparing WW to RT 7 men, aged 62-69 years, selected from a PrCa registry Longitudinal HRQoL during AS (SF-36; Perceived Stress Scale) Change over time (baseline & 12 months later) Burden Qualitative None Burden Longitudinal Reactions to diagnosis (Interviews) Suicide (Swedish registry data) Men without PrCa Frequency Longitudinal Suicide (National Death Index) Frequency Longitudinal HRQoL (EORTC-QLQ-30) during WW Age-, calendar period-, and statematched suicide rates from the general population Change over time (between 4 & 10 years of follow-up) Qualitative Worry, fear, & uncertainty during WW (Interviews) None Burden Johansson et al., 201132 167 men, aged 45-75 years, randomly assigned to WW in SPCG-4 Longitudinal QoL; anxiety; depression (Studyspecific questionnaire) Both Kelly, 200933 14 men, aged 59-83 years, from outpatient clinics Qualitative Impact of diagnosis on body image (Interviews) Population-based control group matched for region and age; also within-subjects change at 2 followup points 9 years apart None Korfage et al., 200634 52 men, aged 60–74 years, enrolled in ERSPC Longitudinal HRQoL (SF-36; EQ-5D) Change over time (before & after diagnosis) Burden Kronenwetter et al., 200535 26 men, aged 50-85 years, participating in the Prostate Cancer Lifestyle Trial (PCLT) 25 men, aged 48-77 years, referred by physicians Qualitative Reactions to diagnosis (Interviews) None Burden Qualitative AS-related uncertainty (Interviews) None Burden 35 men, aged 46-87 years, recruited from PrCa support groups or advertising Qualitative Reactions to diagnosis (Interviews) None Burden Ervik et al., 201027 Fall et al., 200928 Fang et al., 201029 Fransson et al., 200930 Hedestig et al., 200331 Oliffe et al., 200936 Oliffe, 200637 Burden Burden Reeve et al., 201238 163 Medicare beneficiaries, mean age 75.1 years Longitudinal HRQoL & major depression during conservative management (SF-36; Diagnostic Interview Schedule items from MHOS) Cancer-specific QoL during WW (EORTC-QLQ-30+3) Matched non-cancer controls Both Siston et al., 200339 39 men, aged 47-84 years, from 5 VA Medical Centers Longitudinal Change over time (after dx, 3 months & 12 months later) Burden Thong et al., 200940 71 men, aged ≥50 years, identified from a cancer registry Crosssectional HRQoL during AS (SF-36; Quality of Life – Cancer Survivors) Norms for Dutch adult males Burden van den Bergh et al., 201041 129 men, median age 64.6 years at diagnosis, participating in a prospective protocol-based AS program Longitudinal Anxiety & depression (CES-D, MAX-PC) Change over time (2 time points during AS) Both Vasarainen et al., 201142 75 men, aged 60-69 years, enrolled in a prospective AS study (PRIAS) Longitudinal HRQoL (RAND-36) Previously published norms for Finnish adult males Burden Notes: aUnless otherwise noted, in this column “change over time” refers to repeated measures within subjects. bWe defined frequency of harm as the number of people who suffer a specific harm per 1,000 people exposed to the possibility of that harm, or sufficient data to estimate the proportion. We defined burden as an indication of the physical or psychological effects experienced by the patient or family, such as its severity, anticipated duration, treatability, or effect on daily functioning. cAlso includes evidence on harms of diagnosis. dAlso includes evidence on harms of false positive results. Abbreviations (and type of instrument): (GENERAL) BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EQ-5D = A simple health outcomes survey devised by the EuroQol Group; GHQ30 = General Health Questionnaire; GTUS = Growth Through Uncertainty Scale; HADS = Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale; HAI = Health Anxiety Inventory; MHI5 = Mental Health Inventory; MHOS = Medicare Health Outcomes Survey; MUIS-C = Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale Community Form; POMS-SF = Profile of Mood States—Short Form; QoL = Quality of Life; RAND-36 = RAND 36-item Health Survey; SAI-6 = State Anxiety Index, short-form version; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (CANCER – SPECIFIC) EORTC-QLQ-30 & EORTC-QLQ-30+3 = European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life questionnaire; FACT-P = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy— Prostate; IES = Impact of Event Scale; MAX-PC = Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer; QLI = Ferrans & Powers Quality of Life Index-Cancer Version; UCLA-PCI = UCLA Prostate Cancer Index. Other abbreviations: AS = Active Surveillance; CaPSURE = Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urological Research Endeavor Health Survey; ERSPC = European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer; HRQoL = Health-Related Quality of Life; PrCa = Prostate Cancer; PLCO = Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial; PRIAS = Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance study; ProtecT = Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment study; PSA = Prostate Serum Antigen test; RP = Radical prostatectomy; RT = Radiotherapy; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program; SPCG-4 = Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Study Number 4; WW = Watchful Waiting Overdiagnosis of Prostate Cancer Author, Year Study Type Data/Population Outcome(s) of Interest Ciatto et al., 200543 Follow-up of 2 pilot studies 6890 participants in pilot screening studies from 1991 to 1994 Observed excess incidence in screened subjects Davidov & Zelin, 200444 Modeling Hypothetical; assumes that screened population is a random sample from general population Probability of overdiagnosis Draisma et al., 200945 Modeling SEER 9 population aged 50 – 84 years during 1985 – 2000 Overdiagnosis rate Graif et al., 200746 Pathology/Imaging 2,126 men with clinical stage T1c PCa treated with RRP from 1989 to 2005 Possible overdiagnosis, defined as tumor volume less than 0.5 cm3, Gleason less than 7, clear surgical margins, and organ confined disease in the RRP specimen Gulati et al., 201047 Modeling Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) data Percent overdiagnosed at 2 different PSA cut-offs Heijnsdijk et al., 200948 Modeling Simulated cohort of 100 000 men (European standard population) Cases overdetected per 100 screened men Pashayan et al., 200949 Modeling ProtecT study plus UK national statistics and cancer registry data Probability of overdiagnosis Pelzer et al., 200850 Pathology/Imaging 1445 patients undergoing radical prostatectomy and with a PSA level <10 ng/mL Over-diagnosis, defined as a pathological stage of pT2a and a Gleason score of <7 with no positive surgical margins Telesca et al., 200851 Modeling SEER data, plus literature values for other parameters Age- and ethnicity-specific overdiagnosis estimates Tsodikov et al., 200652 Modeling SEER data from nine areas of the U.S. Estimates of overdiagnosis by birth cohort Welch & Albertsen, 200953 Ecological SEER and U.S. Census data Percent overdiagnosed Wu et al., 201254 Modeling Finnish arm of ERSPC Absolute risk of overdetection Abbreviations: ERSPC = European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer; PrCA = Prostate cancer; PSA = Prostate Serum Antigen test; RRP = Radical Retropubic Prostactemy; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program Psychological Harms of Osteoporosis Screening Subjects Study Type Outcomes of Interest (Instrument or Data Source) Comparisona (Time Points) Frequency/ Burden?b Emmett et al., 201255 31 women, aged ≥70-85 years, participating in screening arm of an RCT Qualitative Responses to screening (Interviews) None Burden Green et al., 200656 24 women, aged 45-64 years, whose clinical consultations were recorded; 10 follow-up interviews Qualitative Responses to screening (Recorded clinical consultations; interviews) None Burden Rimes et al., 200257 298 women, aged 32-73 years, recruited by advertising or word of mouth to participate in bone density measurement research Longitudinal Health anxiety; depression; perceived osteoporosis risk (HAI, STAI, BDI & osteoporosis-specific questionnaire) Change over time (before scanning, after results, and at 1 week and 3 month followup) Burden Source Screening Test Diagnosis (Labeling) Bianchi et al., 200558 62 women, aged 50-85 years, with uncomplicated primary OP Crosssectional HRQoL & depression (QUALEFFO-41; Zung Depression Scale) Women of comparable age with another chronic disease (hypothyroidism) Both Dennison et al., 201059 642 men (mean age 64.6 years) & women (mean age 66.6 years) traced through health services registry & enrolled in longitudinal study 30 women, aged 70-85 years, purposively sampled from an RCT, recently screened, & told they were at higher risk of fracture (not formally diagnosed with OP) Longitudinal HRQoL (SF-36) Both Qualitative “Risk-of-illness” experience (Interviews) Osteoporotic, osteopenia, and normal subjects, compared before screening & 4 years later None Salter et al., 201160 Burden Notes: aUnless otherwise noted, in this column “change over time” refers to repeated measures within subjects. bWe defined frequency of harm as the number of people who suffer a specific harm per 1,000 people exposed to the possibility of that harm, or sufficient data for estimation of the proportion. We defined burden as an indication of the physical or psychological effects experienced by the patient or family, such as its severity, anticipated duration, treatability, or effect on daily functioning. Abbreviations (and type of instrument): (GENERAL) BARS = Beck Anxiety Rating Scale; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HADS = Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale; HAI = Health Anxiety Inventory; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF36); STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (OSTEOPOROSIS–SPECIFIC) Mini-OQOL = Osteoporosis Quality of Life scale; QUALEFFO-41 = Quality of life questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis. Other abbreviations: HRQoL = Health-related quality of life; OP = osteoporosis; VFX = vertebral fracture Psychological Harms of Lung Cancer Screening Subjects Study Type Outcomes of Interest (Instrument or Data Source) Comparisona (Time Points) Frequency/ Burdenb 3,925 men and women, mean age 57 years, participating in the Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial (DLCST) Longitudinal Cancer-specific and lung cancerspecific psychosocial consequences of screening (COS; COS-LC) Burden Byrne et al., 200862 341 men and women, mean age 60 years, enrolled in Pittsburgh Lung Screening Study (PLuSS) Longitudinal Anxiety; fear and perceived risk of lung cancer (STAI; 3 items adapted from the PCQ) Kaerlev et al., 201263 4,104 men and women, mean age 57 years, participating in DLCST Longitudinal Prescription of antidepressant or anxiolytic medication Sinicrope et al., 201064 60 initial respondents, male and female, mean age 52 years Longitudinal Lung cancer-related concern (4 items adapted from previously published questionnaire Group randomized to screening vs. group randomized to control; also change over time (COS before randomization & before first screening round; COS-LC at a subsequent screening round a year later) Change over time (before initial CT screening; within 2 weeks of receiving screening results; 6 months and 12 months later Group randomized to screening vs. group randomized to control; 3-year follow-up Change over time (before screening; 1 month after receipt of result; 6 months post-study, after follow-up with pulmonologist Qualitative and Longitudinal Psychosocial consequences of abnormal and false positive lung cancer screening results (Group interviews and COS) Dimensionality, objectivity, and reliability of scale Burden McGovern et al., 2004c 16 Interviews: 9 women and 7 men, aged 5366 years, recruited in the prevalence round of the DLCST; 3 and 2 participated in field test of instrument. 195 initial subjects for survey. 12 men and women, aged 55-74 years, enrolled in the PLCO Qualitative Responses to a false-positive screening test (Focus groups) None Burden van den Bergh et al., 201166 1,466 men and women, aged 50-75 years, participating in the NELSON trial Longitudinal HRQoL; anxiety, and lung cancerspecific distress (SF-12; EQ-5D; STAI-6; IES) Group randomized to screening vs. group randomized to control; also change over time (before randomization; 2 months after baseline scan for those with a negative or indeterminate scan result; at 2-year assessment) Burden Source Screening Test Aggestrup et al., 201261 Burden Frequency Both False-Positive Results Brodersen et al., 201065 van den Bergh et al., 201067 733 men and women, aged 50-75 years, participating in the NELSON trial Longitudinal HRQoL; anxiety, and lung cancerspecific distress (SF-12; EQ-5D; STAI-6; IES) Vierikko et al., 200968 601 asbestos-exposed workers, mean age 65 years Longitudinal Health anxiety and worry about lung cancer (Study-specific questionnaire) Diagnosis (Labeling) Chapple et al., 45 patients with lung cancer, recruited 200469 through various sources; aged 40+ years Qualitative Steinberg et al., 200970 Crosssectional Experiences of lung cancer-related stigma, shame and blame (Interviews) Distress, depression, nervousness (Distress Thermometer; ESAS) 98 men and women newly diagnosed with lung cancer, mean age 63 years Change over time (before randomization; 1 week before baseline scan; 2 months after baseline scan for those with a negative or indeterminate scan result) Change over time (at study outset and 1 year later) in both negative and false positive groups Burden None Burden None Frequency Burden Notes: aUnless otherwise noted, in this column “change over time” refers to repeated measures within subjects. bWe defined frequency of harm as the number of people who suffer a specific harm per 1,000 people exposed to the possibility of that harm, or sufficient data for estimation of the proportion. We defined burden as an indication of the physical or psychological effects experienced by the patient or family, such as its severity, anticipated duration, treatability, or effect on daily functioning. cAlso includes evidence on harms of diagnosis. Abbreviations (and type of instrument): (GENERAL) ; EQ-5D = EuroQol questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety & Depression Scale; HAI = Health Anxiety Inventory; HDRS = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SF-12 = 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; SF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36); STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (CANCER–SPECIFIC) COS = Consequence of Screening questionnaire; COS-LC = Consequence of Screening in Lung Cancer questionnaire; ESAS = Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale; IES = Impact of Event Scale; PCQ = Psychological Consequences Questionnaire. Other abbreviations: HRQoL = Health-related quality of life Overdiagnosis of Lung Cancer Author, Year Study Type Data/Population Outcome(s) of Interest Dominioni et al., 201271 Pathology/Imaging 1,244 smokers (mean age 56.6 years) with 21 screendetected cancers, from general practices in Varese Province, Italy Percent overdiagnosed, defined as screen-detected cancers with volume doubling time > 300 days Hazelton et al., 201272 Modeling Model calibrated to data from 6878 heavy smokers without asbestos exposure in the control arm of CARET; and to 3,642 subjects with comparable smoking histories in PLuSS. Calibration checked using data from the New York University Lung Cancer Biomarker Center (n = 1,021) and Moffitt Cancer Center cohorts (n = 677). Percent overdiagnosed Lindell et al., 200773 Pathology/Imaging 48 screen-detected cancers from 1520 high-risk participants were evaluated for growth rate and morphologic change Percent overdiagnosed, defined as screen-detected cancers with volume doubling time > 400 days Marcus et al., 200674 Follow-up of RCT 6101 participants in the Mayo Lung Project Excess cases in the screened vs. unscreened arms, after 16 years of follow-up Pinsky et al., 200475 Modeling A general convolution model for disease natural history was fitted to screening trial data from the Mayo Lung Cancer Screening Trial Proportion of screen-detected cases, in a population undergoing annual screening, that would never present clinically Sone et al., 200776 Pathology/Imaging 45 cases from 13,037 CT scans of 5480 participants, 4074 years old at the initial CT screening in 1996 Percent overdiagnosed, defined as having expected age of death (calculated from VDT) greater than average Japanese life expectancy Veronesi et al., 201277 Pathology/Imaging From 5203 participants (mean age of 57.7) in a 5-year CT study, 175 study patients diagnosed with primary lung cancer Percent overdiagnosed, defined as screen-detected cancers with volume doubling time > 400 days Yankelevitz et al., 200378 Pathology/Imaging 87 cases of Stage I lung cancer in the MLP and MSK studies Percent overdiagnosed, defined as screen-detected cancers with volume doubling time > 400 days Abbreviations: CARET = Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial; CT = Computed Tomography; MLP = Mayo Lung Project; MSK = Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center project; PLuSS = Pittsburgh Lung Screening Trial; Psychological Harms of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Study Type Outcomes of Interest (Instrument or Data Source) Comparisona (Time Points) Frequency/ Burdenb Longitudinal Depression, anxiety, and HRQoL (HADS; short-form state anxiety scale of the Spielberger state-trait anxiety scale; SF-36; EQ-5D) Burden 10 men, aged 65+ years, under surveillance for an abdominal aorta ≥30 mm, discovered during screening 3 male patients, aged 79-80 years, from a subgroup of patients who suffered a decrease in quality of life (QoL) 12 months after AAA screening & diagnosis Qualitative Reactions to diagnosis and surveillance (Interviews) Positive result vs. negative result vs. controls (not invited for screening (6 weeks after screening); Positive result/surgery vs. positive result/surveillance (3 & 12 months after screening or surgery) None Qualitative Long-term response to diagnosis and surveillance (Interviews) None Burden De Rango et al., 201182 178 patients, aged 50-79 years, under surveillance for small (4.1-5.4 cm) AAAs in the CAESAR trial Longitudinal HRQoL (SF-36) Burden Lederle et al., 200383 567 patients, aged 50 to 79 years, under surveillance for AAAs 4.0-5.4 cm Longitudinal HRQoL (SF-36) Lesjak et al., 201284 Screened men aged 65-74 years, 53 with an abnormal aorta, and 130 with a normal aorta Longitudinal Anxiety , depression, and QoL (HADS; SF36) Spencer et al., 200485 120 screened men with AAA and 245 with a normal aorta; mean age 65–83 years Crosssectional HRQoL, depression, and anxiety (SF-36; EQ-5D; HADS) Patients randomized to undergo endovascular aortic aneurysm repair; also change over time (before randomization, at 6 months and yearly thereafter) Patients randomized to undergo endovascular aortic aneurysm repair; also change over time (before randomization and at clinic visits every 6 months thereafter during the 8-year study) Men with an abnormal aorta vs. those with a normal aorta. Also change over time (before screening; 6 months after screening) Men with AAA vs. men with normal aorta Stanisic and Rzepa, 201286 23 patients, mean age 73.8 years, admitted for surgery to repair asymptomatic AAA Crosssectional Reactions to diagnosis (Studyspecific questionnaire) None Frequency Source Subjects Diagnosis (Labeling) Ashton et al., 67,800 men, aged 65–74 years, enrolled 200279 in the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) Bertero et al., 201080 Brannstrom et al., 200981 Burden Burden Both Burden Notes: aUnless otherwise noted, in this column “change over time” refers to repeated measures within subjects. bWe defined frequency of harm as the number of people who suffer a specific harm per 1,000 people exposed to the possibility of that harm, or sufficient data for estimation of the proportion. We defined burden as an indication of the physical or psychological effects experienced by the patient or family, such as its severity, anticipated duration, treatability, or effect on daily functioning. Abbreviations (and type of instrument): (GENERAL) EQ-5D = EuroQol questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety & Depression ScaleSF-36 = 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36); STAI = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Other abbreviations: CAESAR trial = Comparison of surveillance vs. Aortic Endografting for Small Aneurysm Repair ; HRQoL = Health-related quality of life Psychological Harms of Carotid Stenosis Screening Source Subjects Diagnosis (Labeling) Stanisic and 27 patients, mean age 66.8 years, Rzepa, 201286 admitted for surgery to repair asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis Study Type Outcomes of Interest (Instrument or Data Source) Comparisona (Time Points) Frequency/ Burdenb Crosssectional Reactions to diagnosis (Studyspecific questionnaire None Frequency Notes: aUnless otherwise noted, in this column “change over time” refers to repeated measures within subjects. bWe defined frequency of harm as the number of people who suffer a specific harm per 1,000 people exposed to the possibility of that harm, or sufficient data for estimation of the proportion. We defined burden as an indication of the physical or psychological effects experienced by the patient or family, such as its severity, anticipated duration, treatability, or effect on daily functioning References 1. Archer J, Hayter M. Screening men for prostate cancer in general practice: Experiences of men receiving an equivocal PSA (prostate specific antigen) test result. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2006;7(2):124-34. 2. Bratt O, Emanuelsson M, Grönberg H. Psychological aspects of screening in families with hereditary prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2003;37(1):59. 3. Brindle LA, Oliver SE, Dedman D, et al. Measuring the psychosocial impact of population-based prostate-specific antigen testing for prostate cancer in the UK. BJU Int. 2006;98(4):777-82. 4. Carlsson S, Aus G, Wessman C, Hugosson J. Anxiety associated with prostate cancer screening with special reference to men with a positive screening test (elevated PSA): Results from a prospective, population-based, randomised study. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(14):2109-2116. 5. Chapple A, Ziebland S, Brewster S, McPherson A. Patients’ perceptions of transrectal prostate biopsy: A qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16(3):215-21. 6. Cormier L, Guillemin F, Valéri A, et al. Impact of prostate cancer screening on health-related quality of life in at-risk families. Urology. 2002;59(6):901-906. 7. Evans R, Edwards AG, Elwyn G, et al. ‘It's a maybe test’: Men's experiences of prostate specific antigen testing in primary care. Brit J Gen Practice. 2007;57(537):303-10. 8. Macefield R, Metcalfe C, Lane J, et al. Impact of prostate cancer testing: An evaluation of the emotional consequences of a negative biopsy result. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(9):1335-40. 9. Macefield RC, Lane J, Metcalfe C, et al. Do the risk factors of age, family history of prostate cancer or a higher prostate specific antigen level raise anxiety at prostate biopsy? Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(14):2569-73. 10. Medd JC, Stockler MR, Collins R, Lalak A. Measuring men's opinions of prostate needle biopsy. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(8):662-64. 11. Oliffe J. Anglo-australian masculinities and trans rectal ultrasound prostate biopsy (TRUS-bx): Connections and collisions. Int J Men's Health. 2004;3(1):43-60. 12. Taylor KL, Shelby R, Kerner J, Redd W, Lynch J. Impact of undergoing prostate carcinoma screening on prostate carcinoma‐related knowledge and distress. Cancer. 2002;95(5):1037-44. 13. Fowler Jr. FJ, Barry MJ, Walker-Corkery B, et al. The impact of a suspicious prostate biopsy on patients' psychological, socio-behavioral, and medical care outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(7):715-21. 14. Ishihara M, Suzuki H, Akakura K, et al. Baseline health‐related quality of life in the management of prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2006;13(7):920-25. 15. Katz DA, Jarrard DF, McHorney CA, Hillis SL, Wiebe DA, Fryback DG. Health perceptions in patients who undergo screening and workup for prostate cancer. Urology. 2007;69(2):215-20. 16. McGovern PM, Gross CR, Krueger RA, Engelhard DA, Cordes JE, Church TR. False-positive cancer screens and health-related quality of life. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(5):347-52. 17. McNaughton-Collins M, Walker-Corkery E, Barry MJ. Health-related quality of life, satisfaction, and economic outcome measures in studies of prostate cancer screening and treatment, 1990-2000. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;2004(33):78-101. 18. Perczek RE, Burke MA, Carver CS, Krongrad A, Terris MK. Facing a prostate cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2002;94(11):2923-29. 19. Arredondo SA, Downs TM, Lubeck DP, et al. Watchful waiting and health related quality of life for patients with localized prostate cancer: Data from CaPSURE. J Urol. 2004;172(5):1830-34. 20. Bailey DE, Wallace M, Mishel MH. Watching, waiting and uncertainty in prostate cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(4):734-41. 21. Batista-Miranda J, Sevilla-Cecilia C, Torrubia R, et al. Quality of life in prostate cancer patients and controls: Psychometric validation of the FACTP-4 in Spanish, and relation to urinary symptoms. Arch Esp Urol. 2003;56(4):447-54. 22. Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Nyberg U, et al. Psychiatric treatment in men with prostate cancer–results from a nation-wide, population-based cohort study from PCBaSe sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(14):2195-2201. 23. Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Lambe M, et al. Suicide risk in men with prostate-specific antigen–detected early prostate cancer: A nationwide population-based cohort study from PCBaSe Sweden. Eur Urol. 2010;57(3):390-95. 24. Bisson J, Chubb H, Bennett S, Mason M, Jones D, Kynaston H. The prevalence and predictors of psychological distress in patients with early localized prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2002;90(1):56-61. 25. Burnet KL, Parker C, Dearnaley D, Brewin CR, Watson M. Does active surveillance for men with localized prostate cancer carry psychological morbidity? BJU Int. 2007;100(3):540-43. 26. Daubenmier JJ, Weidner G, Marlin R, et al. Lifestyle and health-related quality of life of men with prostate cancer managed with active surveillance. Urology. 2005;67(1):125-130. 27. Ervik B, Nordøy T, Asplund K. Hit by waves-living with local advanced or localized prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy or under active surveillance. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(5):382-389. 28. Fall K, Fang F, Mucci LA, et al. Immediate risk for cardiovascular events and suicide following a prostate cancer diagnosis: Prospective cohort study. PLoS medicine. 2009;6(12):e1000197. 29. Fang F, Keating NL, Mucci LA, et al. Immediate risk of suicide and cardiovascular death after a prostate cancer diagnosis: Cohort study in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(5):307-14. 30. Fransson P, Damber J, Widmark A. Health-related quality of life 10 years after external beam radiotherapy or watchful waiting in patients with localized prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43(2):119-26. 31. Hedestig O, Sandman P, Widmark A. Living with untreated localized prostate cancer: A qualitative analysis of patient narratives. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(1):55-60. 32. Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: The Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):891-99. 33. Kelly D. Changed men: The embodied impact of prostate cancer. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(2):151-63. 34. Korfage IJ, de Koning HJ, Roobol M, Schröder FH, Essink-Bot M. Prostate cancer diagnosis: The impact on patients’ mental health. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(2):165-70. 35. Kronenwetter C, Weidner G, Pettengill E, et al. A qualitative analysis of interviews of men with early stage prostate cancer: The prostate cancer lifestyle trial. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(2):99-107. 36. Oliffe JL, Davison BJ, Pickles T, Mróz L. The self-management of uncertainty among men undertaking active surveillance for low-risk prostate cancer. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):432-43. 37. Oliffe J. Being screened for prostate cancer: A simple blood test or a commitment to treatment? Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(1):1-8. 38. Reeve BB, Stover AM, Jensen RE, et al. Impact of diagnosis and treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer on health-related quality of life for older Americans: A population-based study. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5679–87. 39. Siston AK, Knight SJ, Slimack NP, et al. Quality of life after a diagnosis of prostate cancer among men of lower socioeconomic status: Results from the veterans affairs cancer of the prostate outcomes study. Urology. 2003;61(1):172-78. 40. Thong MS, Mols F, Kil PJ, Korfage IJ, De Poll‐Franse V, Lonneke V. Prostate cancer survivors who would be eligible for active surveillance but were either treated with radiotherapy or managed expectantly: Comparisons on long‐term quality of life and symptom burden. BJU Int. 2010;105(5):652-58. 41. van den Bergh, Roderick CN, Essink-Bot M, Roobol MJ, Schröder FH, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW. Do anxiety and distress increase during active surveillance for low risk prostate cancer? J Urol. 2010;183(5):1786-91. 42. Vasarainen H, Lokman U, Ruutu M, Taari K, Rannikko A. Prostate cancer active surveillance and health‐related quality of life: Results of the Finnish arm of the prospective trial. BJU Int. 2012;109(11):1614-19. 43. Ciatto S, Gervasi G, Bonardi R, et al. Determining overdiagnosis by screening with DRE/TRUS or PSA (Florence pilot studies, 1991–1994). Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:411–15. 44. Davidov O, Zelen M. Overdiagnosis in early detection programs. Biostatistics. 2004;5(4):603-13. 45. Draisma G, Etzioni R, Tsodikov A, et al. Lead time and overdiagnosis in prostate-specific antigen screening: Importance of methods and context. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(6):374-83. 46. Graif T, Loeb S, Roehl KA, et al. Under diagnosis and over diagnosis of prostate cancer. J Urol. 2007;178(1):88-92. 47. Gulati R, Inoue L, Katcher J, Hazelton W, Etzioni R. Calibrating disease progression models using population data: A critical precursor to policy development in cancer control. Biostatistics. 2010;11(4):707-19. 48. Heijnsdijk E, Der Kinderen A, Wever E, Draisma G, Roobol M, De Koning H. Overdetection, overtreatment and costs in prostate-specific antigen screening for prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(11):1833-38. 49. Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Pharoah P, et al. Mean sojourn time, overdiagnosis, and reduction in advanced stage prostate cancer due to screening with PSA: Implications of sojourn time on screening. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(7):1198-1204. 50. Pelzer AE, Colleselli D, Bektic J, et al. Over‐diagnosis and under‐diagnosis of screen‐vs non‐screen‐detected prostate cancers with in men with prostate‐ specific antigen levels of 2.0–10.0 ng/mL. BJU Int. 2008;101(10):1223-26. 51. Telesca D, Etzioni R, Gulati R. Estimating lead time and overdiagnosis associated with PSA screening from prostate cancer incidence trends. Biometrics. 2008;64(1):10-19. 52. Tsodikov A, Szabo A, Wegelin J. A population model of prostate cancer incidence. Stat Med. 2006;25(16):2846-66. 53. Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment after the introduction of prostate-specific antigen screening: 1986–2005. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1325-29. 54. Wu GH, Auvinen A, Määttänen L, et al. Number of screens for overdetection as an indicator of absolute risk of overdiagnosis in prostate cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(6):1367-75. 55. Emmett CL, Redmond NM, Peters TJ, et al. Acceptability of screening to prevent osteoporotic fractures: A qualitative study with older women. Fam Pract. 2012;29(2):235-42. 56. Green E, Griffiths F, Thompson D. 'Are my bones normal Doctor?' The role of technology in understanding and communicating health risks for midlife women. Sociol Res Online. 2006;11(4). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/11/4/green.html 57. Rimes KA, Salkovskis PM. Prediction of psychological reactions to bone density screening for osteoporosis using a cognitive-behavioral model of health anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40(4):359-81. 58. Bianchi ML, Orsini MR, Saraifoger S, Ortolani S, Radaelli G, Betti S. Quality of life in post-menopausal osteoporosis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3(:78. 59. Dennison E, Jameson K, Syddall H, et al. Bone health and deterioration in quality of life among participants from the Hertfordshire cohort study. Osteoporosis Int. 2010;21(11):1817-24. 60. Salter CI, Howe A, McDaid L, Blacklock J, Lenaghan E, Shepstone L. Risk, significance and biomedicalisation of a new population: Older women’s experience of osteoporosis screening. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(6):808-15. 61. Aggestrup LM, Hestbech MS, Siersma V, Pedersen JH, Brodersen J. Psychosocial consequences of allocation to lung cancer screening: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000663. 62. Byrne MM, Weissfeld J, Roberts MS. Anxiety, fear of cancer, and perceived risk of cancer following lung cancer screening. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(6):917-25. 63. Kaerlev L, Iachina M, Pedersen JH, Green A, Norgard BM. CT-screening for lung cancer does not increase the use of anxiolytic or antidepressant medication. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:188. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/188 64. Sinicrope PS, Rabe KG, Brockman TA, et al. Perceptions of lung cancer risk and beliefs in screening accuracy of spiral computed tomography among high-risk lung cancer family members. Acad Radiol. 2010;17(8):1012-25. 65. Brodersen J, Thorsen H, Kreiner S. Consequences of screening in lung cancer: Development and dimensionality of a questionnaire. Value Health. 2010;13(5):601-12. 66. van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, Scholten ET, van Klaveren RJ, de Koning HJ. Long-term effects of lung cancer computed tomography screening on health-related quality of life: The NELSON trial. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(1):154-61. 67. van den Bergh KA, Essink-Bot ML, Borsboom GJ, et al. Short-term health-related quality of life consequences in a lung cancer CT screening trial (NELSON). Br J Cancer. 2010;102(1):27-34. 68. Vierikko T, Kivisto S, Jarvenpaa R, et al. Psychological impact of computed tomography screening for lung cancer and occupational pulmonary disease among asbestos-exposed workers. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2009;18(3):203-206. 69. Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2004:328(7454:147073. 70. Steinberg T, Roseman M, Kasymjanova G, et al. Prevalence of emotional distress in newly diagnosed lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(12):1493-97. 71. Dominioni L, Rotolo N, Mantovani W, et al. A population-based cohort study of chest x-ray screening in smokers: Lung cancer detection findings and follow-up. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:18. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-18 72. Hazelton WD, Goodman G, Rom WN, et al. Longitudinal multistage model for lung cancer incidence, mortality, and CT detected indolent and aggressive cancers. Math Biosci. 2012;240(1):20-34. 73. Lindell RM, Hartman TE, Swensen SJ, et al. Five-year lung cancer screening experience: CT appearance, growth rate, location, and histologic features of 61 lung cancers. Radiology. 2007;242(2):555-62. 74. Marcus PM, Bergstralh EJ, Zweig MH, Harris A, Offord KP, Fontana RS. Extended lung cancer incidence follow-up in the mayo lung project and overdiagnosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(11):748-56. 75. Pinsky PF. An early- and late-stage convolution model for disease natural history. Biometrics. 2004;60(1):191-98. 76. Sone S, Nakayama T, Honda T, et al. Long-term follow-up study of a population-based 1996-1998 mass screening programme for lung cancer using mobile low-dose spiral computed tomography. Lung Cancer. 2007;58(3):329-41. 77. Veronesi G, Maisonneuve P, Bellomi M, et al. Estimating overdiagnosis in low-dose computed tomography screening for lung cancer: A cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(11):776-84. 78. Yankelevitz DF, Kostis WJ, Henschke CI, et al. Overdiagnosis in chest radiographic screening for lung carcinoma: Frequency. Cancer. 2003;97(5):127175. 79. Ashton HA, Buxton MJ, Day NE, et al. The multicentre aneurysm screening study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2002;360(9345):1531-39. 80. Berterö C, Carlsson P, Lundgren F. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm, a one-year follow up: An interview study. Journal of Vascular Nursing. 2010;28(3):97-101. 81. Brannstrom M, Bjorck M, Strandberg G, Wanhainen A. Patients' experiences of being informed about having an abdominal aortic aneurysm - a follow-up case study five years after screening. J Vasc Nurs. 2009;27(3):70-74. 82. De Rango P, Verzini F, Parlani G, et al. Quality of life in patients with small abdominal aortic aneurysm: The effect of early endovascular repair versus surveillance in the CAESAR trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41(3):324-31. 83. Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. Quality of life, impotence, and activity level in a randomized trial of immediate repair versus surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(4):745-52. 84. Lesjak M, Boreland F, Lyle D, Sidford J, Flecknoe-Brown S, Fletcher J. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Does it affect men's quality of life? Aust J Prim Health. 2012;18(4):284-88. 85. Spencer CA, Norman PE, Jamrozik K, Tuohy R, Lawrence‐Brown M. Is screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm bad for your health and well‐being? ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(12):1069-75. 86. Stanisic M, Rzepa T. Attitude towards one's illness vs. attitude towards a surgical operation, displayed by patients diagnosed with asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm and asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis. Int Angiol. 2012;31(4):376-85. Appendix D. Numbers of studies by outcome and screening service Screening Service Outcome Studies Design Prostate Cancer Crosssectional Outcome Measures k (sample size range) 4 (88-210) General Specific Both 3 0 1 7 (57-4,198) 4 3 0 Anxiety Longitudinal Depression Worry, Intrusive thoughts, Distress, Fear, Uncertainty, Perceived risk, General reactions Health-related quality of life Qualitative 2 (14-16) Crosssectional 3 (88-129) 3 Longitudinal 4 Qualitative 5 (57-569) 0 Crosssectional 5 (31-400) 0 5 0 Longitudinal 6 (57-285) 2 2 2 Qualitative Crosssectional Longitudinal Qualitative Hospitalization, Suicide Longitudinal N/A 0 0 1 0 N/A 11 (7-50) N/A 5 (31-210) 2 2 1 12 (39-569) 1 (16) 4 (registry data) 7 3 1 N/A N/A Screening Service Outcome Studies Design Lung Cancer Crosssectional Anxiety Longitudinal Qualitative Depression Worry, Intrusive thoughts, Distress, Fear, Uncertainty, Perceived risk, General reactions Health-related quality of life Specific Both 0 0 0 4 (341-3,925) 1 3 0 N/A 1 (98) 1 0 0 Longitudinal 0 0 0 0 Qualitative 0 Crosssectional Longitudinal Qualitative N/A 1 (98) 1 0 0 7 (60-3,925) 0 7 0 2 (12,16) Crosssectional Longitudinal N/A 0 0 0 0 6 (195-3,925) 2 (12,16) 1 (4,104) 4 2 0 N/A N/A Studies Design Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm General Crosssectional Qualitative Screening Service k (sample size range) 0 2 (12,16) Longitudinal Prescription of antidepressant medications Outcome Outcome Measures Crosssectional Outcome Measures k (sample size range) 1 (365) General Specific Both 1 0 0 2 (183-1,956) 2 0 0 Anxiety Longitudinal Qualitative Depression Crosssectional Longitudinal 0 N/A 1 (365) 1 0 0 2 (183-1,956) 2 0 0 Qualitative Worry, Intrusive thoughts, Distress, Fear, Uncertainty, Perceived risk, General reactions Health-related quality of life 0 Crosssectional Longitudinal 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 (3,10) Crosssectional 1 (365) 1 0 0 4 (178-1,956) 2 (3,10) 4 0 0 Qualitative Outcome N/A N/A Studies Design Osteoporosis 1 (23) Qualitative Longitudinal Screening Service N/A Crosssectional Outcome Measures k (sample size range) 0 General Specific Both 0 0 0 1 (298) 0 0 1 Anxiety Longitudinal Qualitative Depression N/A Crosssectional 1 (62) 1 0 0 Longitudinal 1 (298) 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 (298) 0 1 0 Qualitative Worry, Intrusive thoughts, Distress, Fear, Uncertainty, Perceived risk, General reactions Health-related quality of life 0 Crosssectional Longitudinal Qualitative Crosssectional Longitudinal Qualitative N/A 3 (24-31) N/A 1 (62) 0 1 0 1 (642) 3 (24-31) 1 0 0 N/A Screening Service Outcome Studies Design Carotid Artery Stenosis Worry, Intrusive thoughts, Distress, Fear, Uncertainty, Perceived risk, General reactions Outcome Measures k (sample size range) 1 (27) General Specific Both 0 1 0 Longitudinal 0 0 0 0 Qualitative 0 Crosssectional N/A