On Viewing Lolita: Art Without Psychoanalysis

advertisement

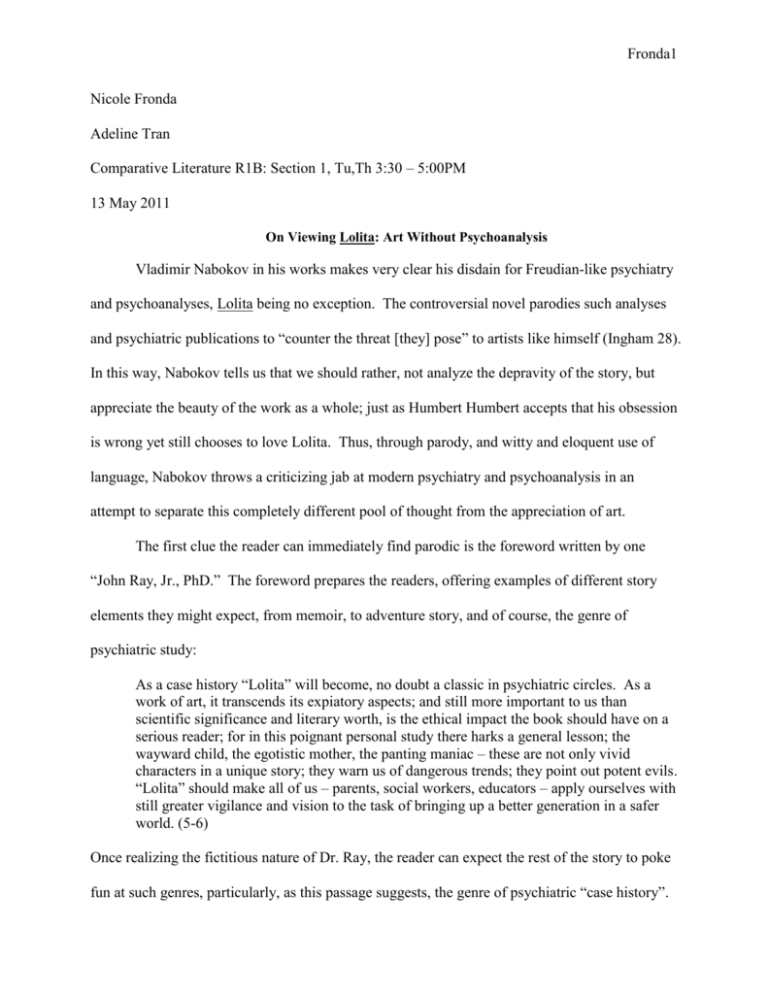

Fronda1 Nicole Fronda Adeline Tran Comparative Literature R1B: Section 1, Tu,Th 3:30 – 5:00PM 13 May 2011 On Viewing Lolita: Art Without Psychoanalysis Vladimir Nabokov in his works makes very clear his disdain for Freudian-like psychiatry and psychoanalyses, Lolita being no exception. The controversial novel parodies such analyses and psychiatric publications to “counter the threat [they] pose” to artists like himself (Ingham 28). In this way, Nabokov tells us that we should rather, not analyze the depravity of the story, but appreciate the beauty of the work as a whole; just as Humbert Humbert accepts that his obsession is wrong yet still chooses to love Lolita. Thus, through parody, and witty and eloquent use of language, Nabokov throws a criticizing jab at modern psychiatry and psychoanalysis in an attempt to separate this completely different pool of thought from the appreciation of art. The first clue the reader can immediately find parodic is the foreword written by one “John Ray, Jr., PhD.” The foreword prepares the readers, offering examples of different story elements they might expect, from memoir, to adventure story, and of course, the genre of psychiatric study: As a case history “Lolita” will become, no doubt a classic in psychiatric circles. As a work of art, it transcends its expiatory aspects; and still more important to us than scientific significance and literary worth, is the ethical impact the book should have on a serious reader; for in this poignant personal study there harks a general lesson; the wayward child, the egotistic mother, the panting maniac – these are not only vivid characters in a unique story; they warn us of dangerous trends; they point out potent evils. “Lolita” should make all of us – parents, social workers, educators – apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world. (5-6) Once realizing the fictitious nature of Dr. Ray, the reader can expect the rest of the story to poke fun at such genres, particularly, as this passage suggests, the genre of psychiatric “case history”. Fronda2 Nabokov already anticipates the psychoanalysis of his story, having a history of psychotherapists persecuting his lead characters “with ideas about primal scenes and Oedipus complexes”, as John Ingham states in his article “Primal Scene and Misreading in Nabokov’s Lolita” (Ingham 28). He recognizes that his novel indeed holds true to such psychiatric archetypes and decides to address this in his foreword, immediately admitting to stereotypes like the “wayward child, the egotistic mother, the painting maniac”. But having a fictitious character suggest that the novel “transcends its expiatory aspects” and teaches readers an important “general lesson”, Nabokov makes the case study seem less sincere, even funny. The “serious readers”, probably referring to the “parents, social workers” and of course psychiatrists, will doubtless take Dr. Ray’s message at face value. The “active and creative reader”, which Nabokov himself urges all readers to be, will realize the story is meant to be a spoof (Course Reader 50). The psychoanalysis of a parody of a psychiatric study won’t reveal any “ethical impact” nor provide any real solution to how readers can “bring up a better generation” as John Ray suggests. The reader should find that the purpose of the novel is not summed up so simply by a fake doctor with a fake degree (in psychiatry most likely) and his overly unnecessary hortatory and didactic tone. Following the phony foreword are the famous opening lines of Humbert Humbert’s confession, the purpose of which he makes quite clear. Whether or not the reader can find the rest of his account genuine, what Humbert very well means to convey to the “ladies and gentlemen of the jury” he already states in the first few paragraphs: Lolita, light of my life, fire or my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta… Did she have a precursor? She did, indeed she did… Oh when? About as many years before Lolita was born as my age was that summer. You can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style. (9) Fronda3 Humbert’s beautiful prose, from the alliteration of beginning consonants, “light of my life” and “my sin, my soul”, the slow rhythm of his syntax, and the overall reverence in his tone as he takes his time describing Lolita like she is a precious work of art makes the readers almost forget the inappropriateness of the situation. Humbert anticipates their disgust and what they will say in response, which is why he answers his own rhetorical questions, including “did she have a precursor?”. This is the type of question he expects them to ask as they begin their psychoanalysis of how his life led to such corruption. He knows the “ladies and gentlemen of the jury” already peg him as a pedophile and murderer so he admits it freely right from the start, pointing out his own “fancy prose style”. In doing so Humbert shows that the intent of his memoir is not to prove his innocence of these offenses or to disprove the existence of his psychiatric disorder, but to show that he truly loves Lolita and is as passionate about her as his artful words express. Psychoanalysis cannot better describe or explain the intensity of Humbert’s infatuation than the words he “lovingly collected” for the beautiful painting of language that is the beginning of the novel (Course Reader 50). Nabokov and Humbert throughout the rest of the novel continually criticize the field of psychoanalysis and its further inadequacies. Firstly, Humbert describes the profession as full of unfulfilled minds as he himself “planned to take a degree in psychiatry as many manqué talents do; but… I switched to English literature” (15). Not only does Nabokov patronize psychiatrists here, disguising his condescension with French as he does often, but also reinstates that literature and psychiatry are two very different disciplines. Secondly, Humbert mocks some of psychiatry’s core theories and practices: “I discovered there was an endless source or robust enjoyment in trifling with psychiatrists: cunningly leading them on; never letting them see that you know all the tricks of the trade; inventing for them elaborate dreams, pure classics in style” (34). Fronda4 Nabokov parodies the stereotypical psychiatric practice of analyzing dreams, showing how Humbert’s psychiatrists are unable to recognize the lack of deeper, subconscious meaning in the dreams he conjures up for them. Nabokov also may be parodying the “classic” novel and the psychoanalysis of that genre - possibly self-consciously alluding to his own “style” of writing which continues to be picked apart by psychiatrists. Nabokov “cunningly” leads them on with “elaborate” plots, themes, and characters, so that they can employ their “tricks of the trade” to understand Humbert’s insanity. Other readers too, not recognizing the irony, may fall for the tricks and fail to look past Humbert’s psychiatric problems to see the real point of the story. To Nabokov, the psychiatric diagnosis of Humbert is an irrelevant, “readymade generalization” that most certainly should not be the basis of the readers’ comprehension and “artistic appreciation” of the novel (Course Reader 49, 50). And to Humbert himself, such a diagnosis fails to sufficiently explain his love for Lolita. Humbert’s love for Lolita is not merely a kind of psychosexual infatuation. While he does act upon his sexual urges, the reason why he is more focused on Lolita than any other nymphet is because he also sees her as a work of art. He even describes her and refers to her as a work of art more often than he refers to her as a real person. And his separation from her compels him to recreate her in his art - his memoir, rewritten journals, and even a lengthy poem. The poem itself in its rhyme scheme, song-like rhythm, the constant repetition of Lolita’s name and tragic ending, resembles Edgar Allen Poe’s poem, Annabel Lee, which Nabokov already frequently references. Poe’s poem is a beautiful piece of literature that needs no psychoanalysis to be understood or appreciated, but Humbert chooses to psychoanalyze his own poem: By psychoanalyzing this poem, I realize it is really a maniac’s masterpiece. The stark, stiff, lurid rhymes correspond very exactly to certain perspectiveless and terrible landscapes and figures and magnified parts of landscapes and figures as drawn by psychopaths in tests devised by their astute trainers. (257) Fronda5 Humbert again willingly admits he is a “maniac”, a “psychopath”, a sick pedophile. He recognizes the poor quality of his poem and compares it to the tests administered to psychopaths by the “astute trainers” which is an obvious reference to psychiatrists. Humbert’s negative attitude towards the poem, calling it “stark, stiff, lurid” and “perspectiveless” show that he feels it is not worthy to be called art, but a perfect example of a psych test. Here Nabokov again distinguishes from the “landscapes and figures” of art from the “magnified parts of landscapes and figures” of such tests by repeating the phrase, showing that they are indeed separate kinds of images. The images of a psych test are not studied for the purpose of art, and vice versa; the images in art should not be studied for psychiatric purposes. Humbert’s initial rationale for creating the poem, after all, was not to later psychoanalyze it and realize his slipping grip on reality, but to remake Lolita in a work of art that entirely explains his passion for her. Nabokov’s and Humbert’s greater overlying purpose for this novel is not to deceive the reader of a great debauchery, to parody genres, or make fun of psychiatry, but to craft an original story for the sake of an original story. John M. Ingham devotes his essay to psychoanalyzing the parody of psychoanalysis in Lolita, attempting to answer the riddle Nabokov himself poses on how authors try to “assert originality when their imaginations have been predicted in advance by the psychoanalyst” (Ingham 28): With the cast of psychoanalytic characters in place, the answer to the riddle emerges. Inasmuch as Humbert is a second Freud, while Quilty personifies Freud and psychoanalysis in the first instance, Nabokov has the Oedipus complex [End Page 44] murder psychoanalysis. By killing Quilty (the first Freud), Humbert (the second Freud and incestuous father) imagines that he rescues Lolita (Dora, mother and daughter) for art and, at the same time, protects her from Quilty's pornography (i.e., psychoanalysis). Humbert murders psychoanalysis and abducts its erotic object. (Ingham 44-45) Ingham’s thorough analysis greatly matches real psych studies of the Oedipus complex. Ingham names Humbert as the “second Freud”, Humbert refers to himself as “King Sigmund the Second” Fronda6 after all (125), and also represents the Oedipus complex, the concept born from the first Freud’s psychoanalytic theory. Quilty “personifies Freud and psychoanalysis”, becoming the father of the second Freud and the Oedipus complex that Humbert’s character stands for in Ingham’s metaphor. However, I do not completely agree with Ingham giving the role of “the first Freud” to Quilty. It is Quilty who follows Humbert and takes Lolita from him, not the other way around. Nevertheless, Ingham’s analysis is well-conceived in his suggestion that with this ironic metaphor Nabokov destroys psychoanalysis with its own theories. It also not only lends to further Nabokov’s parody of psychoanalytic theory, but gives the novel an original spin in its unexpected parody of the expected oedipal outcome. Whether or not Nabokov truly intended for the story to be analyzed in this way, Ingham elegantly discovers the answer to his riddle regarding artistic originality: Humbert “murders psychoanalysis” in the name or art, the “erotic object”, in turn killing the predictions and readymade generalizations against Nabokov’s work, defending his unique creation. Ingham could have taken his critique one step further, however. Not only does the climax sever psychoanalysis from the art of Nabokov’s work, and not only does Humbert commit the crime for the sake of art, but in doing so he also creates art. Humbert does not actually save Lolita from Quilty by murdering him. It is in writing this confession that he preserves Lolita as the work of art he has always perceived her to be. Humbert fully culminates his love for Lolita, succeeding to capture her “perilous magic” (134) that enchants him, and hoping to enchant the minds “of later generations” (309), the creative and active readers, with his book, his “refuge of art” (309), he creates for her. Both Humbert and Nabokov then create an immortalized original story. Critics and scholars like Ingham will continue to dive into its multifaceted design, some using psychoanalysis and some not, in an attempt to discovers its Fronda7 greater meaning of a work as a whole. Whether or not it is found, the plain truth remains that the author meant for Lolita to be an influential, long-lasting piece of literature. From the parody of the Oedipus complex, the self-conscious and almost sarcastic foreword, the critical jibes at psychiatrists, and the immense amount of detail and artful language he uses, Nabokov strongly emphasizes his desire for Lolita to be enjoyed simply as literary “aesthetic bliss” (315). The reader can psychoanalyze all he or she wants and find all the lessons of immorality to be found from such a study. But such a reader would fail to take in all other aspects and not see the whole beautiful, magnificent image the story presents. Humbert sees all that is wrong with himself, with Lolita, with their love, and still boldly shares his story with the world just so others can know it exists. We readers then should admire and appreciate its presentation - the daring, original, deep, and lovingly laid out story and work of art Nabokov offers us. Fronda8 Works Cited Ingham, John M. "Primal Scene and Misreading in Nabokov's Lolita." American Imago 59.1 (2002): 27-52. Project MUSE. Web. 20 Apr. 2011. <http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/american_imago/v059/59.1ingham.html>. Nabokov, Vladimir. “Good Readers and Good Writers.” Course Reader. Spring 2011. Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich. Lolita. New York: Vintage, 1997. Print.

![Adolescence in 20th Century Literature and Culture [DOCX 16.08KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006806148_1-4fb552dd69cbfa44b08b2f880802b1fe-300x300.png)