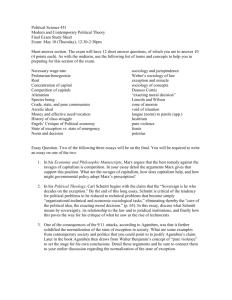

Emory-Jones-Sigalos-Neg-CSUF

advertisement