Leo Strauss` interpretation of Aristotle`s Natural Right Teaching

Leo Strauss’ interpretation of Aristotle’s Natural Right Teaching

André Luiz Cruz Sousa

Ph.D. Student in Philosophy at UFRGS mail-address: andreluizcrs@gmail.com address: Praça Júlio de Castilhos, nº 74, apto 42

CEP: 90430-020/Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil

Abstract

The essay articulates the interpretation of Aristotle’s natural right teaching by XX th century political philosopher Leo Strauss. His interpretation of Aristotle turns out to be not simply the result of an investigation on the history of political philosophy but also the result of an attempt to articulate adequately contemporary political problems (the problem of political exception is specially important), since contemporary political thought (Carl Schmitt is the main interlocutor) was, for

Strauss, unable to do it. The resulting straussian commentary on Aristotle’s natural right is unorthodox because it deviates from both Aquinas’ and Averroës’ conceptions of natural right, which were developments of Aristotle’s teaching. Strauss’ criticism of both medieval variants of natural right results from their incapacity to solve the same contemporary perplexities that moved Strauss to the study of natural right: Aquinas is accused by Strauss of presenting an ethical-theological conception of natural right which is not attentive to grave political problems, whereas the averroists are accused of undervaluing ethics and therefore degrading natural right into a tool for politics (good or bad). Strauss attempts to unite both the requirements of statesmanship and of ethics as the basis of natural right. The essay concludes that, in spite of its unorthodoxy, Strauss’ interpretation of Aristotle’s natural right is in accordance with Aristotle’s perspective on natural right.

The central pages of Natural Right and History

, Leo Strauss’ most famous book, are occupied by an interpretation of aristotelian natural right (δίκαιον φυσικόν) which is unique in its unorthodoxy and originality. It is unorthodox as it deliberately deviates from the most influential and authoritative development of natural right teaching inspired by Aristotle, the thomistic natural right. It is original as it was worked out as an attempt to solve perplexities that Strauss considers to pervade XX th

century political philosophy. Insofar as it brings

Aristotle back to the center of philosophical-political debate, it turns into a contribution both to the tradition of Natural Law and to contemporary political thought.

Two assertions are singled out by Strauss as the focal points of aristotelian natural right. First, that “natural right is a part of political right”; second, that “all natural right is changeable” (1953, p.157). As regards the first assertion, which refers to

Ethica Nicomachea

1134b18-19 (“of political right part is natural and part is legal”/ Τοῦ δὲ πολιτικοῦ δικαίου τὸ

μὲν φυσικόν ἐστι τὸ δὲ νομικόν), there is not much room for polemic, as Strauss simply mentions the hierarchy of forms of “right” (δίκαιον) that culminates in the political right, corresponding to the hierarchy of the forms of human association that culminates in the

political association

1 : “the most fully developed form of natural right is that which obtains among fellow-citizens” (p.157). In other words, natural right is an aspect of the relations among men who “are free and equal according to proportion or arithmetic” (ἐλευθέρων καὶ ἴσων ἢ κατ' ἀναλογίαν ἢ κατ' ἀριθμόν -1134a27-28), i.e., an aspect of the political right existing “among those who have law between them” (οἷς καὶ νόμος πρὸς αὑτούς -1134a30).

The second assertion – “an assertion much more surprising than the first” (p.157) - is the focus of the unorthodox character of Strauss’ interpretation for the same reason that it is the cause of much disagreement among those who comment Aristotle’s natural right: the obscurity of the text, more specifically the fact that “the passage in singularly elusive; it is not illumined by a single example of what is by nature right” (p.156). The origin of the perplexity of the commentators lies in the lack of a clear-cut distinction between the changeability of natural right and the changeability of legal right. For Aristotle, the legal right (δίκαιον

νομικὸν) is the part of the political right “for which as a matter of principle there is no difference whether it is this or that way; once it is established, then there is a difference”

(νομικὸν δὲ ὃ ἐξ ἀρχῆς μὲν οὐδὲν διαφέρει οὕτως ἢ ἄλλως, ὅταν δὲ θῶνται, διαφέρει -

1134b20-21) by which the philosopher means the changeability of legislation according to the exercise of statesmanship: a fixity is established grounded in nothing but the legislative act and therefore is bound to be undone provided that circumstances change and a new legislative act comes into being. The malleability of legal right is evident as Aristotle characterizes it as

“that about which they legislate on particular occasions, for example, to sacrifice to do honor to Brasidas” (ὅσα ἐπὶ τῶν καθ' ἕκαστα νομοθετοῦσιν , οἷον τὸ θύειν Βρασίδᾳ - 1134b23-24).

The commentary on natural right attributes to it a stability which contrasts with the changeability of legal right: “natural [right] is that which has everywhere the same power”

(φυσικὸν μὲν τὸ πανταχοῦ τὴν αὐτὴν ἔχον δύναμιν -1134b19). This stability is, however, attenuated as a way to explain the variability of law and the things political: “there is something among us which is by nature and, nevertheless, entirely changeable ” (παρ' ἡμῖν δ' ἔστι μέν τι καὶ φύσει, κινητὸν μέντοι πᾶν 1134b29-30). The result is that Aristotle seems to attribute to natural right a stability that is absent in legal right, but also a changeability that might be equal or even stronger than that of legal right. The difference between the changeability of natural and legal right is for Aristotle obvious

2

, an opinion that is not shared

1 See Politica Α 1152b12-1253a4 for the coming into being of the city (πόλις), the complete community, from the combination of villages (κώμαι) that come into being from the combination of households (οἴκοι).

2 The philosopher provides the listener/reader with an unhelpful analogy with the hand: “the right hand is by nature the strongest, despite the fact that it is possible for everyone to become ambidextrous” (φύσει γὰρ ἡ δεξιὰ

by his commentators: “among the things that can be otherwise , which are by nature and which are not, but are legal and conventional, since both are equally changeable

, is obvious”

(ποῖον δὲ φύσει τῶν ἐνδεχομένων καὶ ἄλλως ἔχειν, καὶ ποῖον οὒ ἀλλὰ νομικὸν καὶ συνθήκῃ,

εἴπερ ἄμφω κινητὰ ὁμοίως, δῆλον – 1134b30-33).

The lack of precise explanation concerning the changeability of natural right has given room to widely divergent commentaries. Strauss mentions the averroistic and the thomistic variants. According to the averroistic – islamic, jewish or latin 3 – natural right is nothing but

“legal natural right”, a set of broad rules of justice which comes into being everywhere through ubiquitous convention: broad rules with which almost any status quo is in accordance, the preservation of which depends on both the untrue teaching that these rules are universally valid and the occasional disregard of these rules when the preservation of the status quo is in danger. Concerning the thomistic variant, Strauss presents the difference between the universally valid principles of natural right and the mutable specific rules therefrom derived as a qualification , by Aquinas, of the aristotelian statement on the mutability of all natural right: man is endowed with synderesis, a habit of practical principles which enables him to perceive the unchangeable principles and to derive changeable specific rules as the one about the return of the deposits

4

. Synderesis would then satisfy the need for an explication of the changeability of natural right as well as safeguard the stability without which it would be meaningless to speak of natural right.

Strauss criticizes both medieval variants: the averroistic because the way it admits the mutability of natural right “implies the denial of natural right proper” (p.159); the thomistic for introducing a qualification inexistent in the greek text, insofar as “Aristotle says explicitly that all right – hence also natural right – is changeable; he does not qualify that statement in any way” (p.158). Both variants fail in avoiding what Strauss names “the Scylla of

‘absolutism’ and the Charybdis of ‘relativism’” (p.162), a failure that Aristotle would have escaped by means of his natural right teaching characterized by “hesitations and ambiguities”

(p.163) resulting from the considerations of urgency that statesmanship imposes on ethical thought. This hesitation is expressed by Strauss in this fashion: “There is a universally valid hierarchy of ends, but there are no universally valid rules of action” (p.162), which means

κρείττων, καίτοι ἐνδέχεται πάντας ἀμφιδεξίους γενέσθαι -1134b33-35). Needless to say that it does not help to make the interpretation of his natural right teaching clear.

3 Even though Strauss presents a general account of the averroistic interpretation of aristotelian natural right, he names (p.158) Averroës and Marsilius of Padua as, respectively, islamic and latin examples, and indicates in a footnote his own essay “The Law of Reason in the Kuzari”, where he comments the natural right teaching of the jewish medieval author Yehuda Halevi.

4 It is a reference to Summa Theologica II.I., Quaestio XCIV and XCV. We discuss it in the next pages.

that, in certain political circumstances, the most urgent end, despite occupying a lower position in the hierarchy of ends, is preferred to the absolutely best end. The averroistic position, with its use of natural right as a tool for the preservation of the status quo , falls victim to the ‘Charybdis of relativism’: if all right is conventional, therefore natural right is indeed a label that does not mean any stable and fundamental reality behind the mutability of legal right. The thomistic position, in its turn, with its “definiteness and noble simplicity”

(p.163), i.e., its attenuation of the changeability of natural right by means of unchangeable moral laws (“the principles of the moral law, especially as formulated in the Second Table of the Decalogue, suffer no exception, unless possibly by divine intervention” - p.163), falls victim to the ‘Scylla of absolutism’ insofar as it assumes “the basic harmony between natural right and civil society” (p.163), restricting therefore the demands of statesmanship on ethical thought

5

.

A solution is available on condition that Scylla and Charybdis be avoided: “can we find a safe middle road between these formidable opponents, Averroës and Thomas?” (p.159).

Aware of the dangers lying ahead Strauss is both daring and cautious, as the presentation of his position on Aristotle’s natural right is preceded by a brief preface as straightforward as it is humble: as the great thinkers have gone astray “one is tempted to make the following suggestion” (p.159). The starting-point of the suggestion is that Aristotle thinks primarily of concrete decisions instead of general propositions as he speaks of natural right. This corresponds to a straussian distinction between a ‘natural right doctrine’ and a ‘natural law doctrine’. Natural Law in straussian vocabulary 6

translates lex naturalis , i.e., a rule containing a fixed standard, a prescription concerning some conduct. In this sense Aquinas defines ‘law’

( lex ) as regula et mensura actuum – rule and measure of acts (Summa Theologica II.I. Q. XC, art. 1), meaning a fixed standard against which conducts are evaluated. The latin expression had no equivalent in greek, as φύσις (nature) was understood in contradistinction to νόμος

(law): “in light of the original meaning of ‘nature’, the notion of ‘natural law’ (nomos tes physeos) is a contradiction in terms rather than a matter of course” (STRAUSS, 1983, p.138).

Therefore, the expression δίκαιον φυσικόν corresponds to a set of actions or relations among citizens instead of rules and should be translated as ‘natural just’ or ‘natural right’.

5 See this statement by Strauss (p.164): “A work like Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws is misunderstood if one disregards the fact that it is directed against the Thomistic view of natural right. Montesquieu tried to recover for statesmanship a latitude which had been considerably restricted by the Thomistic teaching. What Montesquieu’s private thoughts were will always remain controversial. But it is safe to say that what he explicitly teaches, as a student of politics and as politically sound and right, is nearer in spirit to the classics than to Thomas”.

6 See Strauss’ essay On Natural Law in STRAUSS, 1983, p. 137-146.

Strauss justifies the focus on concrete decisions as the primary seat of natural right with a markedly aristotelian statement: “All action is concerned with particular facts” (p.159).

The statement is accompanied by an example that recalls the inevitability of having recourse to the perspective of the wise man (φρόνιμος) in order to grasp a virtuous action

7

: “It is much easier to see clearly, in most cases, that this particular act of killing was just than to state clearly the specific difference between just killings as such and unjust killings as such”

(p.159). Nevertheless, there are general principles implied in all concrete decisions, and the principles concerning distributive and commutative justice are implied in concrete decisions about right. At this point Strauss risks falling victim to the Scylla of absolutism which he imputes to Aquinas, insofar as these principles could be rephrased as leges such as “distribute power according to worth” or “restore private damages”.

The primacy of concrete decisions requires qualification in order to account for the full changeability of natural right. Strauss singles out a concrete situation the gradation thereof potentially implies fundamental stability or fundamental changeability of the ground for a concrete decision. The situation is “human conflict”: “In every human conflict there exists the possibility of a just decision based on full consideration of the circumstances, a decision demanded by the situation” (p.159). This statement deserves close attention. The situation determines the gradation of human conflict: the typical situation is that of the conflicts addressed by legal right, the principles thereof being the general principles of distributive and commutative justice; in these typical conflicts a full consideration of all the circumstances is not allowed, insofar as the decision which will put an end to the conflict shall be based on the law (νόμος), a general standard the fixity thereof is the very essence of legal right. The officer in charge to take this decision - the juryman (δικάστης) – has the function of restoring the equality of the law against the unjust profit obtained by one part and the damage suffered by the other: “the commutative justice is the middle between damage and unjust profit” (τὸ ἐπανορθωτικὸν δίκαιον ἂν εἴη τὸ μέσον ζημίας καὶ κέρδους – Ethica

Nicomachea 1132a18-19). In other words, the concrete decision that solves a normal conflict has as its ground the fundamental stability of the principles of commutative and distributive justice, a stable natural right. The full consideration of the circumstances, nevertheless, remains a possibility in any conflict according to Strauss. This possibility is realized when a human conflict gains density up to a point that it endangers the possibility of solving typical

7 See Ethica Nicomachea 1113a15-1113b2 where the desire of the good, as distinguished from the desire of the merely apparent good, is defined as the desire of the good man, who is able to see the true good in each action as if he was a rule and a measure of them .

conflicts in accordance with laws. This conflict is the “extreme situation”: “let us call an extreme situation a situation in which the very existence or independence of a society is at stake” (p.160). Examples of extreme situations are war and espionage against foreign powers and subversive elements within society, situations that bring to light an aspect of natural right which is prior to the principles of distributive and commutative justice, i.e., the common good

(p.160). Under normal conflicts the common good is equivalent to the efficacy of the principles of justice specified in legal right. However, under the extreme human conflict “the common good [...] comprises [...] the mere existence, the mere survival, the mere independence of the political community in question” (p.160). The adjective “mere” is noteworthy insofar as it signs the momentary reversal of the hierarchy of ends, putting the lower-in-rank but more urgent (public safety) over the better (principles of justice) by virtue of statesmanship’s demands: “only in such situations, it can justly be said that public safety is the highest law” (p.160). The urgency is generated by the action of those whose inventiveness enables them to transform a situation which previous experience had taught as being normal into an extreme situation: “natural right must be mutable in order to be able to cope with the inventiveness of wickedness” (p.161). It is in the nature of urgency to be as unpredictable as the inventiveness of those who bring it about: “there is no principle which defines clearly in what type of cases the public safety, and in what type of cases the precise rules of justice, have priority” (p.161). Insofar as natural right contains both the general principles of legal right and the concern with public safety, it is both fundamentally stable and fundamentally mutable, as it implies both the general and coherent conception of justice behind the particular dispositions of legal right and the legally and morally unlimited action needed to face those whose aim is to subvert this conception.

Having managed to escape the Scylla of absolutism that he imputes to the thomistic natural law teaching, Strauss has, nevertheless, by means of his interpretation of Aristotle’s teaching, come close to the averroistic position that he accuses of denying natural right. The author is aware of his proximity to Charybdis, and thus, following his interpretation of the aristotelian statements on natural right he differentiates it from “Machiavellianism” (whose thought is similar to averroistic political thought). The difference is a consequence of the definitive reversal, in Machiavellianism, of the hierarchy of ends according to which the peaceful application of rules of justice is superior to war and urgency: Machiavelli takes his bearings by the extreme situation within which the considerations of urgency are paramount in such a way that “he does not have to overcome the reluctance as regards the deviations from what is normally right” (p.162); the aristotelian statesman, in his turn, taking his

bearings by the aforementioned hierarchy of ends, once faced with the extreme situation,

“reluctantly deviates from what is normally right” (p.162).

The reluctance of the statesman faced by the potential boundlessness of an action taken under the impact of urgency is the moral ground of natural right that opposes the straussian position to both averroistic and thomistic variants. Strauss sees in the statesman’s action the full actualization of an aristotelian ethics characterized by the restraint of innate low impulses (“man is so built that he cannot achieve the perfection of his humanity except by keeping down his lower impulses”- p.132-133), as the statesman concerns himself with the moral perfection of a community and not only with his own individual moral perfection

8

. The extreme situation forces the statesman to take a concrete decision concerning the community’s moral perfection which is a critical decision as it may direct him to courses of action similar to the courses of action taken by the people who menace the existence of the community

9

. Only a statesman who is himself a φρόνιμος, a wise good man, will experience this decision as critical, as a decision that constitutes perhaps the most extreme example of the contingency of moral action. In the reluctance of this statesman (which is due to the necessity, fostered by the radical contingency of the extreme situation, to realize an action that his previous experience would indicate to be repellent) it becomes clear that “politics is the field on which human excellence can show itself in its full growth and on whose proper cultivation every form of excellence is in a way dependent” (p.133-134). Considerations of this sort would be alien to a bad man acting to preserve any status quo in accordance with the averroistic natural right teaching: “it is the hierarchic order of man’s natural constitution which supplies the basis for natural right as the classics understood it” (p.127).

The critical stance of the statesman who needs to act outside the scope of fixed standards of action in order to enable other men to act in accordance with them, understood as a political demand of the utmost ethical relevance, points to the reason why Strauss finds thomistic eminently ethical but barely political natural law teaching unsatisfactory. For

Aquinas, Natural Law ( Lex Naturalis ) has the fixity of a participation in the rational creature of the divine providence that governs the totality of the universe 10 . The rational creature is

8 STRAUSS, 1953, p.133: “Serious concern for the perfection of a community requires a higher degree of virtue than serious concern for the perfection of an individual”.

9 Commenting his own example of war as an extreme situation, STRAUSS (1953, p.160) affirms: “A decente society will not go to war except for a just cause. But what it will do during a war will depend to a certain extent on what the enemy – possibly an absolutely unscrupulous and savage enemy – forces it to do. There are no limits which can be defined in advance, there are no assignable limits to what might become just reprisals”.

10 Consider these statements: “assuming the world to be ruled by divine providence [...], it is obvious that the whole community of the universe is governed by divine reason” ( Manifestum est autem, supposito quod mundus divina providentia regatur [...] quod tota communitas universi gubernatur ratione divina - Summa Theologica

naturally inclined to the proper acts and ends insofar as his reasoning is derived from principles naturally known

11

or “principles imparted to him which are some general rules and measures of everything done by man” ( principia ei naturaliter indita, sunt quaedam regulae generales et mensurae omnium eorum quae sunt per hominem agenda – Summa Theologica

II.I, Quaestio XCI, Art. 3). Aquinas allies stability and changeability by means of a distinction between “first common principles” ( prima principia communia ), the rectitude of which is the same in all cases and known by everyone, and “specific principles which are as conclusions of the common principles” ( quaedam propria, quae sunt quasi conclusiones principiorum comunium ), the rectitude of which obtains in all cases ‘for the most part’ ( ut in pluribus ) since

“it is liable to failure in few cases” ( ut in paucioribus potest deficere )

12

. This occasional failure that accounts for the changeability of Natural Law is due to exceptional circumstances that challenge strict interpretation of a human law ( lex humana ) shaped on the conclusiones of

Natural Law: Aquina’s favorite examples are the conclusiones

“deposits shall be restituted”

( deposita sint reddenda

) and “you shall not kill” ( non esse occidendum ), which can fail by virtue of the contingency of things human, a failure that nevertheless does not affect the eternal validity of Natural Law’s principles wherefrom they are derived, respectively, “act according to reason” ( secundum rationem agatur

) and “do evil to nobody” ( nulli esse malum faciendum )

13 . In this same fashion, precepts of the Decalogue such as “Do not kill” (

Non occides

) “are absolutely in Natural Law” ( sunt absolute de lege naturae – Summa Theologica

II.I, Quaestio C, Art.1).

So alien is Lex Naturalis to the problem of political exception that the treatment of salus hominum is part of the discussion concerning de potestate legis humanae , i.e., the power of human law: there Aquinas asserts that a law shall not be obeyed if observatio talis legis sit

II.I, Q. XCI, Art.1); “among the other kinds, the rational creature is subject to divine providence in a more excellent way [...] in itself is participated eternal reason through which it has natural inclination towards the right act and end. This participation of eternal law in the rational creature is called natural law” ( Inter cetera autem rationalis creatura excellentiori quodam modo divinae providentiae subiacet [...] in ipsa participatur ratio aeterna, per quam habet naturalem inclinationem ad debitum actum et finem. Et talis participatio legis aeternae in rationali criatura lex naturalis dicitur – Summa Theologica II.I, Q. XCI, Art.2).

11 “all raciocination is derived from principles naturally known” ( omnis ratiocinatio derivatur a principiis naturaliter notis – Summa Theologica II.I, Q. XCI, Art.2)

12 Summa Theologica II.I, Q.XCIV, Art.4. for the distinction between the first principles of Natural Law and their conclusions. It is recaptured in Art.5 where the changeability of Natural Law is discussed: “as regards the first principles of the law of nature, the law of nature is entirely immutable. As regards the second precepts, which we affirmed to be as some specific conclusions close to the first principles [...] it can change in some particular aspect in few cases” ( quantum ad prima principia legis naturae, lex naturae est omnino immutabilis.

Quantum autem ad secunda precepta, quae diximus esse quasi quasdam proprias conclusiones propinquas primis principiis [...] Potest tamen immutari in aliquo particular, et in paucioribus ).

13 For “act according to reason” as a first principle of Natural Law and the conclusion “deposits shall be restituted” see Summa Theologica II.I, Q. XCIV, Art.4. For “you shall do evil to nobody” and its conclusion

“you shall not kill”, see Q. XCV, Art.2.

damnosa communi saluti – if observation of such a law be harmful to common safety (Summa

Theologica II.I, Quaestio XCVI, Art.6). The example is a city under siege which cannot obey a law such as “the doors of the city shall remain closed” ( portae civitatis maneant clausae ) because some citizens who protect the city in question are being hunted by enemy soldiers: in such a case it is recommended to act contra verba legis, ut servaretur utilitas communis or

“against the words of the law, in order that the common utility be preserved”. In other words, necessitas non subditur legi , necessity is not subdued to law. The exceptional situation is caused by an inherent flaw of political activity that does not seem to put any challenge to the nucleus of Lex Naturalis

: “since the legislator cannot grasp all singular cases, [he] sets forth a law according to that which happens in most cases” (

Quia igitur legislator non potest omnes singulares casus intueri, proponit legem secundum ea quae in pluribus accident ). This is the characteristic treatment of Epieikeia – Summa Theologica II.II, Quaestio CXX – where the example of the law concerning the restitution of deposits reappears as a matter of acting

“having overlooked the words of the law” ( praetermissis verbis legis ): Thomas is strict as he affirms that epieikeia correspondet proprie iustitiae legali or “epieikeia corresponds properly to legal justice”.

Putting aside the aforementioned ‘aloofness’ of

Lex Naturalis as regards these conclusiones principiorum -undermining cases, their exceptionality is not the radical exceptionality of what a XX th

century thinker as Strauss names “extreme situation”: to deny the restitution of something deposited to a man gone crazy or intending to attack the city as well as to open the gates of a city under siege in order to let some citizens to come into it, is to offer a more subtle interpretation of legal right and therefore to act under the protection of political stability sustaining legal right, whereas Strauss’ extreme situation requires an action beyond legal right to allow for the possibility to act in accordance with legal right . The existence of a political situation that is fundamental in relation to the laws – “all laws depend on human beings. Laws have to be adopted, preserved and administered by men” (p.136) – is also manifest in Strauss’ discussion of πολιτεία, which should not be translated as

‘constitution’ insofar as it is not, strictly speaking, legal (“ Politeia is not a legal phenomenon.

The classics used politeia in contradistinction to ‘laws’” – p.136). In a suggestion that recalls

Aristotle’s statement in

Politica Γ – “the politeia is some order among those who inhabit the city” (ἡ δὲ πολιτεία τῶν τὴν πόλιν οικούντων ἐστὶ τάξις τις – 1274b38) – it is affirmed that

πολιτεία is some form of arrangement of people in regard to political power (p.136). In this sense, an organized action strong enough to menace this arrangement (the nature of which determines some specific form of distributive and commutative justice that underlies legal

right as a stable natural right) will require, in order to sustain the arrangement, a reaction which might operate outside the rules of justice that specify it: the boundless action that keeps the possibility of law-abiding action is the entirely changeable natural right.

***

The unique interpretation of natural right is the culmination of concerns and perplexities that moved the young Strauss: Aristotle’s political philosophy proved itself able to shed light over problems arisen and unsolved by contemporary political thought. Foremost among contemporary thinkers who raised these problems is Carl Schmitt, whose Der Begriff des Politischen was the subject of a commentary by Strauss. Faced with the instability that plagued the fragile Weimar Republic, rendering its legal rules unable to order society, Schmitt discusses the ‘condition of exception’ (Ausnahmezustand) as a non-legal ordering against imminent anarchy and chaos that could result from the dissolution of the state

14

. Given law’s failure to maintain order - “in its absolute form the exceptional case has arisen only when it is necessary to foster the situation within which legal prescriptions can be valid” (in seiner absoluten Gestalt ist der Ausnahmefall dann eingetreten, wenn erst die Situation geschaffen werden muß, in der Rechtssätze gelten können – SCHMITT, 1922, p.19) – it is characteristic of the exception that it cannot be determined with the clarity of a legal subsumption, that is, neither the facts that constitute the exception nor the acts to be pursued in order to put an end to it can be defined beforehand (p.14). It requires the action of a figure, the Sovereign (der

Souverän), who is simultaneously part of normally valid legal order and is above it, insofar as the focal point of his action is the decision “if the constitution can be in toto suspended” (ob die Verfassung in toto suspendiert werden kann – p.14).

Equally important for our purposes as these thoughts which bear an obvious influence on Strauss’ understanding of the relation between legal and natural right is his criticism of

Schmitt’s hesitant and potentially insufficient treatment of the fundamental philosophical teaching that could serve as a basis for the aforementioned thoughts concerning political exception. This teaching concerns itself with ‘the political’ (das Politische) as a domain that cannot be reduced to moral, economics or any other domain of things human. As an

14 “Has this condition emerged, then it becomes clear that the state must remain, whereas the law steps back.

Since the condition of exception is something quite different from any anarchy or chaos, there remains in juridical sense always an order, however not a legal order” (Ist dieser Zustand eingetreten, so ist klar, daß der

Staat bestehen bleibt, während das Rech zurücktritt. Weil der Ausnahmezustand immer noch etwas anderes ist als eine Anarchie und Chaos, besteht im juristischen Sinne immer noch eine Ordnung, wenn auch keine

Rechtsordnung- SCHMITT, 1922, p.18).

autonomous domain, the political is built around the distinction between friend and enemy

15

, a distinction that is not derived from any criteria pertaining to another domain of things human: politically, the enemy (Feind) corresponds to the greek πολέμιος or the latin hostis – the public enemy – not the ἐχθρός or inimicus who is the target either of feelings such as hate or of unfavorable moral judgment (p.27-28). The public nature of both friend and enemy implies association and dissociation in the highest possible degree: the enemy “is existentially something other and strange” (existenziell etwas anderes und Fremdes ist- p.26) in such a way that “in the extreme case conflicts with him are possible that cannot be decided […] by means of a previously established general rule” (im extremen Fall Konflikte mit ihm möglich sind, die weder durch eine im voraus getroffene generelle Normierung, noch [..] entschieden warden können- p.26). Conflict means war, which is not the end or content of the political but, understood as “the real possibility of physical killing” (die reale Möglichkeit der physischen Totung – p.31), determines a specific political behavior (p.33). The political, which comes to light when the state of exception is in force, divides friend from enemy and allows for the possibility of friends to coexist in accordance with the laws.

Strauss criticizes Schmitt for not carrying on his criticism of liberalism – the political stance that denies ‘the political’ 16

– until its peak, that is, until the point in which an encompassing philosophical view is elaborated to be opposed to liberalism. Against the liberal leveling of the political along with the other domains of things human under the genus

‘culture’ (STRAUSS, 2007, p.101-102), Strauss laments that Schmitt does not develop an insight contained in his own statement to the effect that the distinction between opposites characteristic of the political “is not equivalent and analogous to those other distinctions”

(jenen anderen Unterscheidunge zwar nicht gleichartige und analoge) 17 . This development would propose the political as fundamental in regard to other domains insofar as “the affirmation of the political is the affirmation of man’s dangerousness” (p.112). The lack of an encompassing philosophical view wherein the affirmation of the political would be grounded implies that the development of Schmitt’s insight about the priority of the political would culminate in a philosophy of belligerent nationalism: his affirmation of the political would have “no normative meaning but an existential meaning only” (keinen normativen, sondern

15 “The specific political distinction, to which all political actions and motives can be traced back, is the distinction between friend and enemy” (Die spezifisch politische Unterscheidung, auf welche sich die

Politischen Handlungen und Motive zurückführen lassen, ist die Unterscheidung von Freund und Feind –

SCHMITT, 1932, p.25).

16 See Der Begriff des Politischen , p.63-72 and the annexed text Die Zeitalter der Neutralisierungen und

Entpolitisierungen in SCHMITT (1932).

17 See SCHMITT (1932, p.25) and STRAUSS (1996, p. 102).

nur einen existenziellen Sinn)

18

and would therefore consist in an eulogy of the desire to fight on the basis of any serious conviction (p.120). Consequently, “warlike morals seem to be the ultimate legitimation for Schmitt’s affirmation of the political”, that is, “the affirmation of fighting as such, wholly irrespective of what is being fought for” (p.112 and 120).

The conciliation between statesmanship demands and an ethical understanding of man that provides a theoretical framework against which political problems can be adequately articulated (that is, a theoretical framework that neither overlooks these problems by virtue of apolitical ethics nor articulates them into the belligerent politics of the averroists, Machiavelli or Schmitt) is realized in aristotelian political philosophy. Through his non-antiquarian study of Aristotle

19 , Strauss brings the Stagirite’s thought to articulate contemporary politics 20

(despite the fact that he only hints at these issues in introductory remarks of his books and dedicates himself actually to interpretations of classical texts). The unorthodoxy of his interpretation of natural right, insofar as it calls the old concept to articulate modern facts, actualizes the main characteristic Aristotle attributes to natural right, i.e., “having the same force everywhere” (πανταχοῦ τὴν αὐτὴν ἔχον δύναμιν). The unorthodoxy might actually be unavoidable for theoretical treatment of the theme: as the inventiveness of devices to bring chaos into politics is unlimited, not only natural right but also natural right teaching, if it is to investigate the perpetual in politics, must also be “entirely changeable” (κινητὸν πᾶν).

***

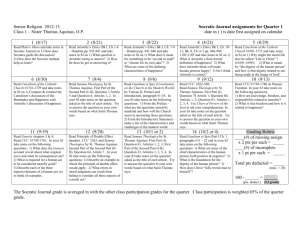

In order to provide the reader with direct access to the core of the argument presented in this essay the table below shows, on the left side, some statements made by Leo Strauss in his commentary of Aristotle’s natural right teaching and, on the right side, statements made by Carl Schmitt on exception and the nature of things political. The idea is to make manifest the way how Strauss reaches Aristotle as a thinker whose thought enables one to solve the incapacity of Schmitt’s political philosophy to provide an adequate conceptual articulation of

18 See SCHMITT (1932, p.46) and STRAUSS (1996, p. 112).

19 See the opening lines of The City and Man : “It is not self-forgetting and pain-loving antiquarianism nor selfforgetting and intoxicating romanticism which induces us to turn with passionate interest, with unqualified willingness to learn, toward the political thought of classical antiquity” (STRAUSS, 1964, p.1).

20 See, for instance, the introductory remarks of The City and Man (1964, p. 1-12) and Liberalism: Ancient and

Modern (1968, p. VII-XI) where the author mentions the incapacity of both liberalism and contemporary academy to understand the relation between the West and Communism. The introductory remarks in Natural

Right and History (1953, p. 1-8) are noteworthy as Strauss comments on United States’ Declaration of

Independence and laments that the words therein contained are undervalued by americans themselves in what seems to him to be an intellectual victory of relativism and nihilism characteristic of the political power recently defeated (Nazi Germany) over the victorious side (United States).

the problems he correctly diagnoses in modern politics. It is important to keep in mind that whereas Strauss comments extensively on Aristotle’s natural right only in

Natural Right and

History , Schmitt treats of exception in several of his writings and, therefore, statements similar to the ones presented in the table as well as in the essay could be found throughout his work.

Leo Strauss’

Natural Right and History

“All action is concerned with particular situations. Justice and natural right reside

[…] in concrete decisions rather than in general rules” (p.159)

“In every human conflict there exists the possibility of a just decision based on full consideration of all the circumstances, a decision demanded by the situation” (p.159)

“In extreme situations there may be conflicts between what the self-preservation of society requires and the requirements of commutative and distributive justice” (p.160)

“There are no limits which can be defined in advance, there are no assignable limits to what might become just reprisals” (p.160)

“there is no principle which defines clearly in what type of cases the public safety, and in what type of cases the precise rules of justice, have priority” (p.161)

Carl Schmitt’s

Der Begriff des Politischen and Politische Theologie

“The decision about the exception is actually a decision in eminent sense . A general norm, as it represents the normally valid legal prescription, cannot ever grasp an absolute exception and therefore cannot also justify the decision according to which a real exceptional case has happened” (Die

Entscheidung über die Ausnahme ist nähmlich im eminenten Sinne Entscheidung.

Denn eine generelle Norm, wie sie der normal geltende Rechtssatz darstellt, kann eine absolute Ausnahme niemals erfassen und daher auch die Entscheidung daß ein echter

Ausnahmefall gegeben ist, nicht restlos begründen - P.T., p.13)

“Condition of exception. To that pertains actually an unlimited authority as a matter of principle, which is the suspension of the whole existing order” (Ausnahmezustand.

Dazu gehört vielmehr eine prinzipiell unbegrenzte Befugnis, das heißt die

Suspendierung der gesamten bestehenden

Ordnung – P.T., p.18)

“It can neither be determined with the clarity of a subsumption when a situation of necessity is in force, nor can it be enumerated

(as regards the content) what it is allowed to happen in such a case, if there is really a situation of necessity and the attempt to end it” (Es kann weder mit subsumierbarer

Klarheit angegeben werden, wann ein Notfall vorliegt, noch kann inhaltlich aufgezählt werden, was in einem solchen Fall geschehen darf, wenn es sich wirklich um den extremen

Notfall und um seine Beseitigung handelt

[…] Der Verfassung kann höchstens angeben, wer in einem solchen Falle handeln

“A decent society will not go to war except for a just cause. But what it will do during a war will depend to a certain extent on what the enemy – possibly an absolutely unscrupulous and savage enemy – forces it to do” (p.160)

“the public safety is not the highest law in normal situations; in normal situations the highest laws are the common rules of justice”

(p.161)

“What cannot be decided in advance by universal rules, what can be decided in the critical moment by the most competent statesman on the spot” (p.161) darf - P.T., p.14)

“The political enemy […] is the other, the foreign […] so that in an extreme situation conflicts with him are possible, and which can be decided neither through general normativity established beforehand nor through the sentence of an uninvolved and therefore unpartisan Third Part” (Der politische Feind […] ist eben der andere, der

Fremde […] do daß in einem extremen Fall

Konflikte mit ihm möglish sind, die weder durch eine im voraus getroffene generelle

Normierung, noch durch den Spruch eines

‘unbeteiligten’ und daher, ‘unparteischen’

Dritten entschieden werden können – D.B.P., p.26).

“In its absolute form the state of exception is in force only when it is necessary to foster the situation within which the legal prescriptions can be valid. Each general norm requires a condition of normality as regards behavior so that its content can be enforced…” (In seiner absoluten Gestalt ist der Ausnahmefall dann eingetreten, wenn erst die Situation geschaffen werden muß, in der Rechtssätze gelten können. Jede generelle Norm verlangt eine normale Gestaltung der

Lebensverhältnisse, auf welche sie tatbestandmäßig Anwendung finden soll… -

P.T., p.19)

“The sovereign […] decides not only whether there is a situation of necessity, but also what shall happen in order to end it. He is outside the normally valid legal order and nevertheless is part of it, insofar as he is responsible for the decision whether the constitution can be suspended in toto

”(der

Souverän […] entscheidet sowohl darüber, ob der extreme Notfall vorliegt, als auch darüber, was geschehen soll, um ihn zu beseitigen. Er steht außerhalb der normal geltenden Rechtsordnung und gehört doch zu ihr, denn er ist zuständig für die

Entscheidung, ob die Verfassung in toto suspendiert werden kann – P.T., p.14)

References

ARISTOTLE (1894). Ethica Nicomachea . Edited by I.Bywater. Oxford Classical Texts.

________ (1957). Politica . Edited by W.D.Ross. Oxford Classical Texts.

SCHMITT, Carl (1932). Der Begriff des Politischen . Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

________ (1922). Politische Theologie: vier Kapitel zur Lehre von Souveränität . Berlin:

Duncker & Humblot.

STRAUSS, Leo (1953). Natural Right and History . The University of Chicago Press.

________ (1983). Studies in Platonic Political Philosophy . The University of Chicago Press.

________ (1964). The City and Man . The University of Chicago Press.

________ (1968). Liberalism Ancient and Modern . The University of Chicago Press.

________ (1996). Notes on Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political . Translated by Harvey

Lomax in SCHMITT, Carl. The Concept of the Political . The University of Chicago Press.

THOMAS AQUINAS (2005).

Suma Teológica

. Vol IV and VI. Latin-portuguese text. São

Paulo: Edições Loyola.