UK HC Dublin transfer to Sweden

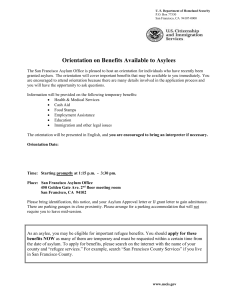

advertisement