Kyphosis

advertisement

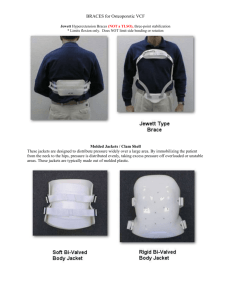

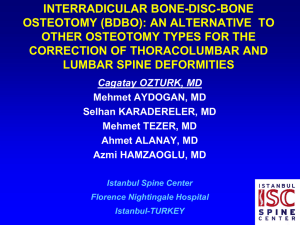

What Is Kyphosis? Kyphosis is a larger-than-normal forward bend in the spine, most commonly in the upper back. In adults, 3 forms of kyphosis are seen: Post-traumatic kyphosis is most commonly in the mid- to lower-back of affected patients, often found in patients who have fractured one or several of their vertebra due to a traumatic injury. It can also occur if there is severe ligament damage in the spine associated with a fracture. Age-associated kyphosis results from the aging process and, more specifically, conditions like osteoporosis, muscle weakness, degenerative disc disease, and spine fractures. Scheuremann’s kyphosis that developed in adolescence can progress into adulthood. A patient with this form of kyphosis has a spine that is stiff due to the abnormal shape of the vertebrae. Post-traumatic Kyphosis Post-traumatic kyphosis occurs most commonly in the mid- to lower-back. Kyphosis of this kind is typically found in patients with severe fractures and neurologic deficits such as quadriplegia or paraplegia. (See Figures 1A-1C) One example of kyphosis is post-laminectomy kyphosis. In rare instances, the spine will develop a forward bend after a common procedure (laminectomy) used to treat spinal stenosis (pinched nerves) in adults – especially if many levels are decompressed. Figure 1A-C. Post traumatic kyphosis can result from an injury going undetected or unrecognized. It can also result from inadequate surgical treatment. Symptoms Progressive kyphosis can develop when there is major spine injury. This type of kyphosis can result in chronic, disabling pain: • Spinal muscle fatigue • Chronic swelling • Progressive degeneration of the spine • Pinched nerve(s) • Problems with sitting balance with severe kyphosis • Skin alterations in paraplegic patients with severe kyphosis Evaluation/Diagnostics • X-ray detects fracture and helps determine the type of fracture. • MRI evaluates any pressure on the nerves that could cause neurologic and motor symptoms • CT scan provides enhanced imaging when x-ray is not sufficient and/or the physician identifies other reasons it is needed; commonly used to evaluate spinal fractures. • Biopsy can rule out tumors, infection or other conditions as the underlying cause of compression fracture. Treatment Nonoperative Treatment Goals of treatment for kyphosis includes curve correction, spine stabilization, pain alleviation, and improved neurologic function. The treatments shown below do not necessarily take into account the kyphosis patient who has osteoporosis. Numerous medications—e.g., Calcitonin, Forteo (teriparatide)—are now available; while they may decrease the pain, they cannot correct kyphosis. Current treatment options include: • Physical therapy • Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication. • Braces to support the spine and decrease muscle spasm Operative Treatment If these conservative measures do not help, surgery may be necessary to control pain and improve deformity or decompress nerve roots. Posterior spinal fusion and instrumentation alone is often used to treat more flexible deformities. Fixed deformities often require more complex surgery. Age-associated Hyperkyphosis Age-associated hyperkyphosis is a pronounced forward bend in the upper spine found in older adults. Sometimes called Dowager’s hump or gibbous deformity, this type of kyphosis makes mobility difficult and increases the risk of falls and fractures. Hyperkyphosis can stem from a number of spinal conditions, like osteoporosis, muscle weakness, degenerative disc disease, and vertebral fractures, or a combination of these. Symptoms • • • • Pain Difficulty with movement and performing activities of daily life Stiffness Reduced height Imaging Evaluation Standing x-rays are typically used to assess hyperkyphosis. Elderly patients, however, can be xrayed lying on their backs. Using the x-ray, the physician will measure the degree of the forward-bending angle to determine the severity of kyphosis. Treatment Options Nonoperative Treatment • Physical therapy • Targeted daily exercise, under the guidance of a physician and/or a physical therapist, can help to strengthen core muscles key to preventing further progression of kyphosis • Bracing and similar orthotic devices have shown some promise for age-associated kyphosis but have not been rigorously tested Operative Treatment If these conservative measures do not help, surgery may be necessary to control pain and improve deformity or decompress nerve roots. Scheurmann’s Kyphosis Figures 1 and 2. Magnified image of wedged vertebrae in Scheuremann’s kyphosis Scheuremann’s kyphosis is a structural kyphosis that typically develops during adolescence, causing the kyphotic spine to become rigid, and sometimes progresses into adulthood. In the spines of these patients, the front sections of the vertebrae grow more slowly than the back sections. Instead of normal and rectangular with ideal alignment, the vertebrae are wedge-shaped and cause misalignment (Figures 1 and 2). The abnormal kyphosis is best viewed from the side in the forward-bending position where a sharp, angular abnormal kyphosis is clearly visible. Figures 2 and 3. Lateral x-ray of a patient with Scheuremann's disease, and close-up x-ray demonstrating wedge-shaped vertebrae characteristic of Scheuremann’s disease. Symptoms & Imaging Evaluation • Symptoms include poor posture and back pain. • Standing x-rays are usually the best way to evaluate and monitor Scheuremann’s kyphosis. Treatment Options Nonoperative treatment • • Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) like ibuprofen or acetaminophen Physical therapy & exercise to strengthen muscles and ultimately help alleviate pain Operative treatment Spinal Fusion If kyphosis has become severe (greater than 80 - 90°) and causes frequent back pain, surgical treatment may be recommended. Surgery provides significant correction without the need for postoperative bracing. Pedicle screws are placed, 2 per vertebra, and connected with 2 rods. This process promotes gentle straightening of the spine. Most surgeries are performed from the back; however, some physicians recommend additional surgery on the front of the spine. Patients are usually able to return to normal daily activities within 4 to 6 months following surgery. Smith-Peterson Osteotomy Moderately flexible curves often straighten simply from lying face down; however, rigid curves may require surgical intervention. The Smith-Peterson osteotomy involves cutting the bone in the back of the spine that connect the facet joints. The removal of this bone and the joints allows the spine to move backwards into extension or more of an upright position. This type of osteotomy is commonly performed during the surgical treatment of Schuermann's kyphosis.