Organization of Thesis

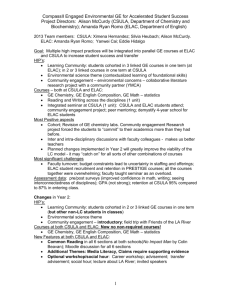

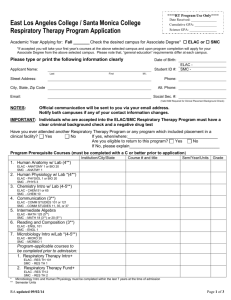

advertisement