DOC - Researching Multilingually

advertisement

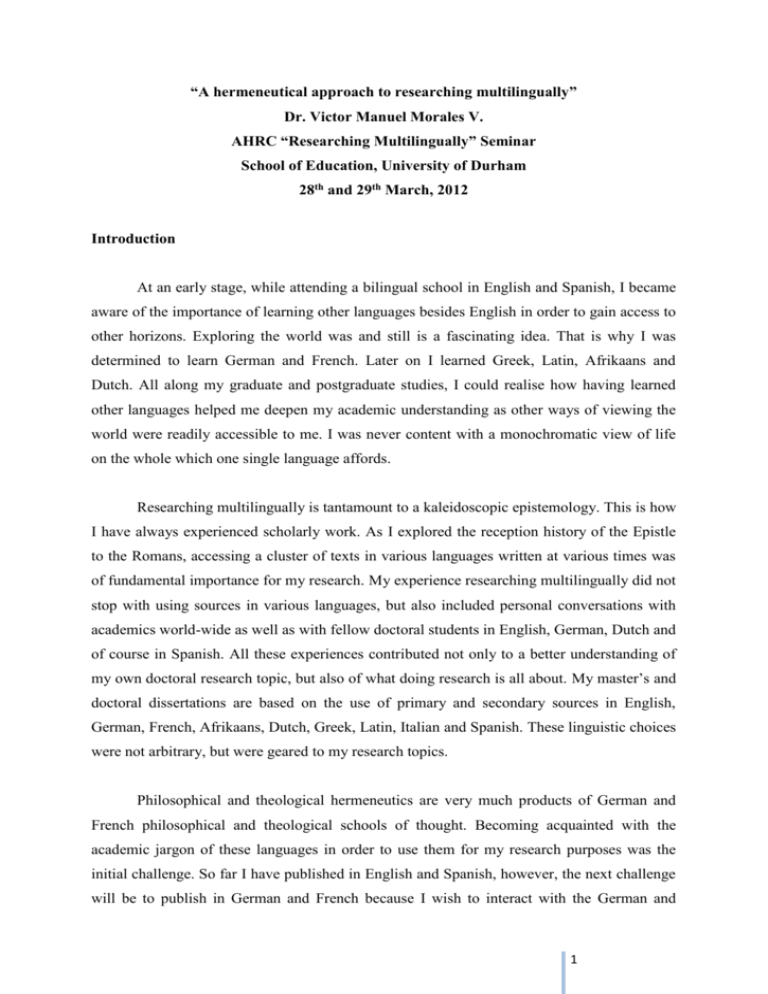

“A hermeneutical approach to researching multilingually” Dr. Victor Manuel Morales V. AHRC “Researching Multilingually” Seminar School of Education, University of Durham 28th and 29th March, 2012 Introduction At an early stage, while attending a bilingual school in English and Spanish, I became aware of the importance of learning other languages besides English in order to gain access to other horizons. Exploring the world was and still is a fascinating idea. That is why I was determined to learn German and French. Later on I learned Greek, Latin, Afrikaans and Dutch. All along my graduate and postgraduate studies, I could realise how having learned other languages helped me deepen my academic understanding as other ways of viewing the world were readily accessible to me. I was never content with a monochromatic view of life on the whole which one single language affords. Researching multilingually is tantamount to a kaleidoscopic epistemology. This is how I have always experienced scholarly work. As I explored the reception history of the Epistle to the Romans, accessing a cluster of texts in various languages written at various times was of fundamental importance for my research. My experience researching multilingually did not stop with using sources in various languages, but also included personal conversations with academics world-wide as well as with fellow doctoral students in English, German, Dutch and of course in Spanish. All these experiences contributed not only to a better understanding of my own doctoral research topic, but also of what doing research is all about. My master’s and doctoral dissertations are based on the use of primary and secondary sources in English, German, French, Afrikaans, Dutch, Greek, Latin, Italian and Spanish. These linguistic choices were not arbitrary, but were geared to my research topics. Philosophical and theological hermeneutics are very much products of German and French philosophical and theological schools of thought. Becoming acquainted with the academic jargon of these languages in order to use them for my research purposes was the initial challenge. So far I have published in English and Spanish, however, the next challenge will be to publish in German and French because I wish to interact with the German and 1 French academic community. Such an opportunity will arrive once I start writing my Habilitation. I am thoroughly convinced that global concerns cutting across cultural horizons demand interdisciplinary as well as multilingual (interlingual) approaches to doing research. A. Intercultural and interdisciplinary communication in research and between researchers as the horizon of multilingualism I am particularly interested in exploring the multilingual aspect of doing research in the areas of reception studies and hermeneutics. Let me share this afternoon some initial thoughts. I shall start with some fundamental reflections on the nature of language and history as two basic constituents of understanding human experience, which is the Gegenstand, that is, the object of enquiry of the humanities and social sciences. I give an account of my own experience of researching multilingually, in the hope that my thoughts can contribute to the philosophical foundations of this academic aspect. Broadly speaking, hermeneutics concerns itself ultimately with the problem of understanding. The insights of Wilhelm Dilthey, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur, Hans Robert Jauss and Jürgen Habermas have opened up a new area of research by working out the implications of the interface between language and history in relation to understanding. This is particularly important for the humanities and the social sciences since their objects of enquiry are precisely the product of human actions which always display meaning and call for interpretation From this angle, language is not conceived of anymore as a tool at our disposal. It is rather the framework within which we come to understand the multiplicity of experiences life present us with including those of the academic sort. There are never worldless words nor wordless worlds. Language is part and parcel of who we are. It shapes our self, providing us with a bundle of perspectives from which we can constantly gain knowledge of the world. In fact, it is the way through which we are epistemologically linked to the world and to others. Metaphorically, Gadamer describes this lingual relationship to the world and to others as the horizons of human experience. A horizon depicts the specific place at a given time where a partial view of the whole is afforded. 2 Social relationships take place within language and history. In one way or another, human beings are always involved in processes introducing changes in the world they inhabit. By and large, human actions always display meaning in the sense that they always occur within a given context where they become relevant or irrelevant. In other words, they are inscribed in social networks always mediated by language and history. To be sure, these become part and parcel of communicative processes which stand at the basis of any social exchange whose end product is the transformation of our world and, most importantly, of ourselves. As South Africans put it, “Umntu ngumntu ngabantu” (we find our humanity in community). Individuals and their actions can only be fully understood in the light of their various social relationships. Becoming who we are is a long learning process of becoming acquainted with the world as displayed by the language or languages we are given and by the ways of being brought forth by the communities surrounding us. Regarding scientific knowledge, following the example of Kant’s critique of pure reason, a milestone in the realm of the natural sciences, Dilthey concerned himself with laying the epistemological foundation for those disciplines studying human experience and its historical objects which are per se unique and at odds with any generalisation in the form of laws. As Jean Grondin explains: “Wenn die Hermeneutik sich den Regeln und Methoden der Verstehenswissenschaften widmet, so erscheint sie berufen, als methodisches Fundament aller Geisteswissenschaften (Literaturwissenschaft, Geschichte, Theologie, Philosophie und der heute so genannten „Sozialwissenschaften“) zu dienen” (Grondin, Hermeneutik, 10). (If hermeneutics concerns itself with rules and methods in the sciences of understanding, it seems then to be called to serve as the methodological foundation for the sciences of the spirit (literary studies, history, theology, philosophy, and the so called social sciences)) He claimed that these products of the human spirit must be understood in their uniqueness. In other words, what is their significance? Since their meaning was a matter of interpretation, devising an appropriate methodology became a central problem for him. Language held the key to solve the riddle. From a German perspective, research in the humanities and the social sciences rely heavily on the role language plays. But what is language? From the hermeneutical tradition, language is communication. We address others and others address us. This communicative aspect of the Lebenswelt (lifeworld) of the academic communities underpins the relevance of researching multilingually. 3 Researchers communicate with their contemporary peers as well as with a host of forerunners and their works through which new avenues of research are laid open. At this juncture, the Jauss’ concept of reception plays such a key role since it highlights not only the interconnections and discontinuities between the insights of fellow researchers, past and present, but also between disciplines. This state of affairs can either be depicted either as a constant fusion of horizons occurring at different levels (Gadamer) or as conflicting paradigms (Jauss and Kuhn). However, what is evident here is that researchers and their object of enquiry are intrinsically bound. The same applies to the relationship between academic disciplines, where locating points of intersection can spark scholarly imagination and the ensuing development of science. To put it differently, it is only through an interplay of questions and answers , that is, by means of dialogues, arguments and disagreements among scientific communities occurring in space and time that our understanding of the subject matter can be widened. But how can this ongoing interplay of questions and answers happen in academic communities across the globe? This is a chief concern regarding academic communication and interlingual scholarship. In relation to this, to my mind, first of all, it is imperative that each academic community play an active part in securing for a given language a place at the scholarly table. The formation of an academic tradition for a given language is the responsibility of its users who should sponsor local research culture. It goes without saying that it is only through written language, that is, texts, that such a status can be achieved. The academic potential of a given language must be cultivated. Surely, the success of a research project depends on how well its relevance as well as its findings can be communicated. However, at this point, we are faced with another dilemma: global audiences presuppose multiple cultural horizons, which can never be fully accounted for given the limitations entailed by any communication process. Here again, decisions regarding the most effective way of communicating the research results to a wider community or communities are inevitable. Academic communities should not only engage in sponsoring interdisciplinary research projects, but also interlingual approaches to the various research fields. And, in the same way that formulating appropriate questions, and fixing the boundaries to our object of enquiry are two equally important decisions, on which a whole research project hinges, its interlingual context will presuppose making decisions as to what languages are relevant at a given moment. 4 Normally, we tend to think that objectivity, as the fundamental premise under which natural sciences operate, can only be effectively communicated with the use of a single language stripped off any reference to personal experiences. In this case, language is nothing but a tool or medium to communicate measurable results and their validity to all the members of the scientific community, leaving no room for potential misunderstanding. Mathematics has traditionally fulfilled such a role. But what can be said regarding the humanities and social sciences? Does the quest for a perfect language actually do justice to the particularities of the field? Do intercultural research communities necessarily presuppose interlingual cooperation? As said, human experience is plural, dynamic and unpredictable. However, should scholarly communication reflect this plurality? As for Western civilization, Greek, Latin, French, and English have all been historical frameworks for scholarly communication not only due to political and economic reasons, but also to its extensive use by scientific communities for communication purposes. Consequently, this situation has led to the monopoly of monolingual research communication. En passant, the monopoly of a given language in scientific circles also corresponds to its predominance in other cultural spheres, say, entertainment. However, these various dominating languages have also contributed to the formation of the legacy of scientific terminology. If research culture ought to become not only interdisciplinary but also interlingual, what are the tasks to be accomplished in order to enable it? How can this interlingual research culture be effective sponsored? Certainly, all these questions are philosophically framed by the age-old problem between universal forms and particular cases. Some postmodern philosophers believe in the impossibility of real communication between communities since, arguably, one language is incommensurable with another. “The language games take place in local communities; they are heterogeneous and incommensurable. Highly refined expressions in one language, such as poetry, cannot be translated into another without change of meaning. There exists no universal metalanguage, no universal commensurability” (Kvale, Truth, 22). Universal linguistic incompatibility between communities is problematic to any attempt of researching multilingually. I shall not deal with this issue here. However, the hermeneutical view I have advanced here represents a constructive position. As argued, at least for the humanities and social sciences the historical limitation of human knowledge underpins their research endeavours and results. The open-ended character of human knowledge can only be epistemologically accounted for by what Ricoeur termed the 5 hermeneutic arch, that is, the continual shifts between explanation and interpretation which can never reach a definitive end. Such an image depicts the constant sides in dynamic processes present in any communicative action. “La hermenéutica sigue siendo el acto de discernir el discurso en la obra. Pero esto (sic) discurso no es dado en otra parte que en y a través de las estructuras de la obra” (Bengoa, De Heidegger a Habermas, 108) (Hermeneutics still is the act of understanding the discourse in the work. But this discourse is only given in and by the structures of the work) Given the complexities of today’s cultural life, the scholarly panorama of 21st century resembles more a puzzle whose connecting pieces fail to provide us with the full image, simply because such an image remains under construction. An appropriate scientific language for humanities and social sciences must reflect such a state of affairs. The historical dimension of research entails shifting perspectives, more like variations on one theme. From a hermeneutical point of view, meaning is never settled once and for all, but is always the result of the interaction of interpreters and their objects of knowledge within a given context. In this respect, a plurality of languages implies a plurality of perspectives and approaches pointing out the limitations of any attempt of ever reaching absolute knowledge of anything at all, including self-knowledge. Researchers can never distance themselves from their objects of enquiry because of the effects language (or languages), and history (traditions) have on their own understanding and on the research questions they formulate. Definitely, interlingual research projects resonate with the open possibilities of any human enterprise and experience. B. Reception studies and multilingualism The concept of reception was central to my doctoral dissertation. I set out to research the historical semantic growth of a controversial text such as chapter 13 of the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Romans. There the Apostle Paul dealt broadly with the issue of civil obedience in the context of the early churches in Rome. This text however played a key role in the formation of Christian political thought before the dawn of Modern Age, and after the Second World War. Reception studies amount to exploring the processes and outcomes of scholarly fusions of horizons and paradigm changes, whereby previous perspectives on a particular issue and concerns are linked to one another producing new vantage points from which a deepened knowledge and a heightened awareness of a subject matter can be gained. In the 6 case of my dissertation, the main task was to chart the historical journey of Paul’s instructions as understood by latter readers in new settings in order to grasp their meaning in a much fuller scope for its appropriation by present readers. That implied working multilingually with a plurality of contexts. On the whole, reception studies are grounded in the recognition of the historical growth of the meaning of any cultural product or event. By extension, theories and methodologies count as cultural academic products. Hence, the concept of reception can have a wider application across the social sciences beyond literary studies, philosophy, theology and art history. I believe that researching their historical and actual appropriation in various cultural contexts has to be conducted multilingually and interlingually. For instance, in which ways Piaget’s theory on intelligence has been understood and applied in Latin America in the past decades? Are there further developments the in Spanish and Portuguese worlds inspired by his views? The various interpretations, appropriations and criticisms represent the global legacy of his views on intelligence. Conclusion Every language entails world-views, stories, presuppositions, agreements and discontinuities which are part and parcel of the way we come to understand the world and ourselves. If this is true, researching multilingually is not only a valuable methodological asset to any research programme but the fundamental condition for scholarship in global and intercultural contexts. From the hermeneutical tradition, interlingual scholarship is tantamount to a research paradigm most suitable for the interests and goals of the humanities and social sciences which are per se interpretative sciences. It is a fundamental skill which ought to be fostered born out of the need to engage with others in an ongoing conversation across the globe stretching out to long past worlds, while keeping an eye on the future. Many thanks. 7 Bibliography cited: Anderson, W.T. (ed.), The Truth about the Truth: De-confusing and Re-constructing the Postmodern World (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/ Putnam, 1995) Bengoa Ruiz de Azúa, J., De Heidegger a Habermas: Hermenéutica y fundamentación última en la filosofía contemporánea (Barcelona: Herder, 2002) Grondin, J., Hermeneutik (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009) Kvale, S., “Themes of Postmodernity” in The Truth about the Truth: De-confusing and Reconstructing the Postmodern World (W.T. Anderson (ed.); New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/ Putnam, 1995) pp.18-25 8