12654393_DigitalDensities_paper_final

advertisement

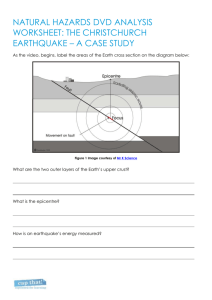

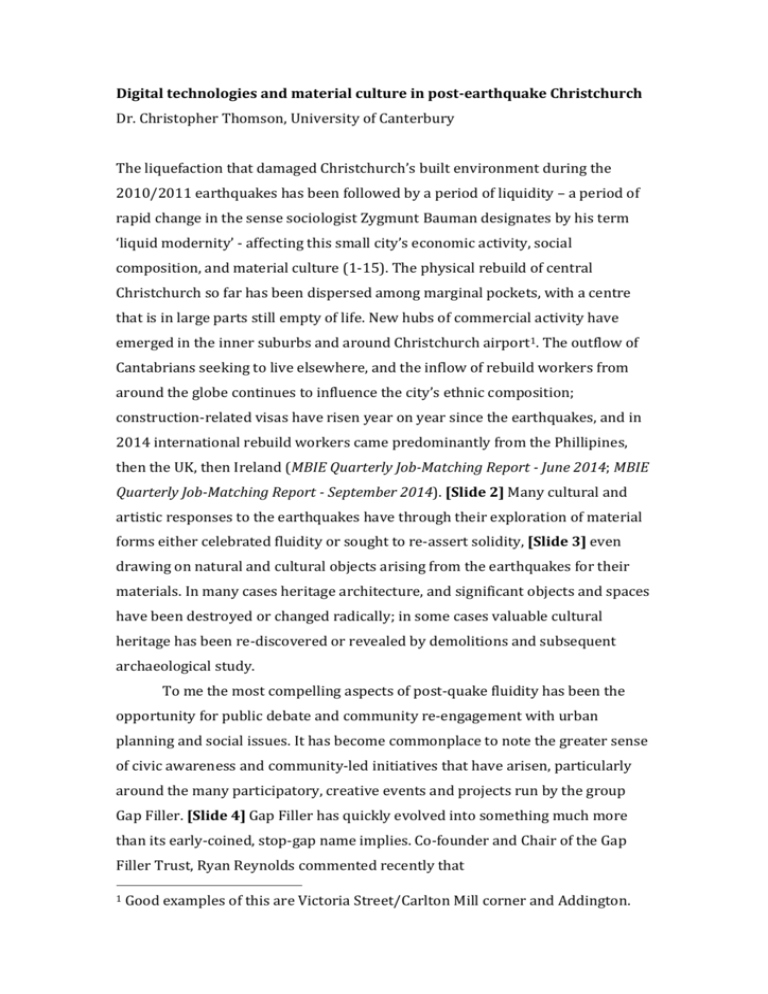

Digital technologies and material culture in post-earthquake Christchurch Dr. Christopher Thomson, University of Canterbury The liquefaction that damaged Christchurch’s built environment during the 2010/2011 earthquakes has been followed by a period of liquidity – a period of rapid change in the sense sociologist Zygmunt Bauman designates by his term ‘liquid modernity’ - affecting this small city’s economic activity, social composition, and material culture (1-15). The physical rebuild of central Christchurch so far has been dispersed among marginal pockets, with a centre that is in large parts still empty of life. New hubs of commercial activity have emerged in the inner suburbs and around Christchurch airport1. The outflow of Cantabrians seeking to live elsewhere, and the inflow of rebuild workers from around the globe continues to influence the city’s ethnic composition; construction-related visas have risen year on year since the earthquakes, and in 2014 international rebuild workers came predominantly from the Phillipines, then the UK, then Ireland (MBIE Quarterly Job-Matching Report - June 2014; MBIE Quarterly Job-Matching Report - September 2014). [Slide 2] Many cultural and artistic responses to the earthquakes have through their exploration of material forms either celebrated fluidity or sought to re-assert solidity, [Slide 3] even drawing on natural and cultural objects arising from the earthquakes for their materials. In many cases heritage architecture, and significant objects and spaces have been destroyed or changed radically; in some cases valuable cultural heritage has been re-discovered or revealed by demolitions and subsequent archaeological study. To me the most compelling aspects of post-quake fluidity has been the opportunity for public debate and community re-engagement with urban planning and social issues. It has become commonplace to note the greater sense of civic awareness and community-led initiatives that have arisen, particularly around the many participatory, creative events and projects run by the group Gap Filler. [Slide 4] Gap Filler has quickly evolved into something much more than its early-coined, stop-gap name implies. Co-founder and Chair of the Gap Filler Trust, Ryan Reynolds commented recently that 1 Good examples of this are Victoria Street/Carlton Mill corner and Addington. “With the massive and controlling city plan that’s underway, Christchurch is in some key respects an even more rule-bound society than previously, despite the chaos and disorder. This inflexibility makes something like the ‘transitional city’ movement both crucial and probable – the carving out of spaces and times where the little people are asserting creative impulses and self-determination.” (n.p.) Reynolds’s important point is that the urban planning for the rebuild has been characterized by a strong reaction against fluidity, and that perhaps the defining question for Christchurch continues to be how to balance the needs of government and commercial property developers with the evolving needs of people, community groups, and businesses. In exploring alternatives to the topdown approach, Gap Filler has developed “techniques to liberate space and engender fluidity” (n.p.); one of many such experiments is the cycle-powered cinema on screen, which was set up on the former site of an iconic bike shop and screened films about NZ’s cycling history, all powered by members of the audience on bicycles. This need for this type of approach has been registered in the IT sphere by Stephen Judd, when he commented on the government’s grand plans for a high-value, high rent central city ‘Innovation Precinct’. Although it adopted the language of startup tech innovation, it has failed to appeal to startups, or even medium-sized IT businesses because it was too expensive and seemingly failed to understand that the city needed to replace its low-rent, marginal spaces in order to attract the next wave of IT innovators (Judd). [Slide 5] Before moving to my main topic, I’d like to turn consider another Gap Filler project, this time an architectural example. The Arcades Project, a series of 6.3 metre high archways that together can form an open-air arcade, was a centerpiece of the 2013 Festival of Transitional Architecture (FESTA). It “was born from a desire for new ways to add movable infrastructure to empty sites for community and public events. Designed to be reconfigurable and relocatable, the structures have the potential to enliven vacant sites around Christchurch for the next 25 years . . . While the shape of the arches references Christchurch’s rich Gothic Revival architectural heritage, the design’s strippedback engineered timber frames hint at a possible architectural future for the city” (“FESTA - The Arcades Project”). The project’s name alludes to Walter Benjamin’s monumental, unfinished work of the same name, which was a study of the Parisian shopping arcades of the 19th century. Most interestingly from my perspective, is the connection between the fragmentary, collection-like structure of Benjamin’s study, and the implied purpose(s) of the Arcades Project to “enliven vacant sites”. The Arcades Project opens up questions about how we experience walking through the city, what kinds of activities can take place, and what kinds of authority govern these activities. The Gap Filler Arcades Project is about imagining possible experiences, about the substitution of many kinds of activities, about use and reuse. This is true literally because it is designed to enables events of different forms to take place: markets, speeches, music gigs, art works, and so on. It seems to me that it points to the importance of material connections with history, but refuses to be bound by them. It stands in stark contrast to Christchurch’s other homage to the Parisian arcades, the suburban shopping centre known as The Tannery [lower right in slide 5]. In short, I think the Arcades Project is suggestive of the ways digital media interacts with our sense of our physical environment. Writing about a digital photography, Michelle Henning asks, “What difference does it make if people encounter these technologies, not as the absolutely new but in the form of repetitions, continuities or revivals?” Referring to other writings by Benjamin, she explains his distinction “between two types of repetition or reworking: one which, in returning to a distant past, de-naturalises the present, reminds us of the unfulfilled promise of earlier times; the other which smooths over change, presenting the new in continuum with the old, as the heir to what went before” (223). Gap Filler’s Arcades Project represents a kind of challenges us to denaturalise the present, while the Tannery provides a smooth and pleasurable transition as it invites us to experience many of our old shops behind ‘brand new’ 19th century facades. The tensions Henning identifies, and which we see emerging in architectural forms are also visible in some of the most interesting digital media projects seen in Christchurch recently, to which I now turn. I’ve suggested that Christchurch is experiencing a sharper awareness of its historical present, but I will focus now on a specific aspect of this sense of historicity: I want to ask how are digital media and data-driven applications part of the response to the need for re-imagining and revitalising Christchurch’s urban centre? Is there a relationship between digital media and urbanism that would inform our understanding of the rebuild? How are such representations related to the physical transformations of the city and material experiences of its citizens? And is the distinction between material change as a primary cause and digital media as an immaterial representation or response too simplistic? There is a now a rich literature on the connections between digital media, networked computing, and the shaping of urban material cultures. Much less has addressed the post-disaster context, like we face in Christchurch, where it is more a case of re-build rather than re-new. In what follows I suggest that Lev Manovich’s well-known distinction between narrative and database as distinct but related cultural forms is a useful framework for thinking about the Christchurch rebuild, and perhaps urbanism more generally. In short, Manovich argues that distinct from narrative, which is the representation of events, the database is an exemplary cultural form, one that “represents the world as a list of items which it refuses to order” (85). Manovich argues that collections, encyclopaedias, dictionaries and spreadsheets are all instances of this ‘database form’, as are database-driven websites and apps. I suggest that the database form has been prominent in Christchurch because it is better suited to representing spatially dispersed, multiple, and emergent patterns of experience that have arisen in the fluid post-quake situation. [Slide 6] CityViewAR is an augmented reality app created by the Human Interface Technology Lab at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch. Its initial purpose was to enable users to explore Christchurch after the earthquakes. Using a mobile phone or tablet, users could see 3D models of damaged or demolished heritage buildings overlaid on the real landscape rendered by their device’s camera. The platform was subsequently adapted for a heritage project entitled High Street Stories, which provides a curated collection of images, video, histories, vignettes and interviews that explore the uses of the High Street district over time. The CityViewAR platform has also been adapted for use on the (now not to be publicly released) Google Glass platform(“Augmented Reality For Glass » CityViewAR for Glass”); and for a prototype called ‘BuildAR’, which, although not fully realized yet, aims to help planners and architects visualize building projects by providing the possibility of multiple 3D models of the same space. This would mean multiple architectural models for a site (such as alternate future designs) could be simulated. High Street Stories is the fullest application of the platform so far, and gives access to content that can be explored either via the AR mobile app or through the project’s website (“High Street Stories”). What interests me about High Street Stories is the combination of a database driven, collection-like structure, and its explicit focus on stories as the content within that structure. The history of the High Street area is told through a variety of narratives focusing on industrial history, stories about retail, cultural uses such as art galleries and music venues, personal memoir, and stories about illicit practices like prostitution and the drugs trade. Is this de-naturalising the present, or smoothing it over? My initial sense of the intention behind the design of AR interfaces is that they aim to create a continuous experience, despite mobile network limitations that might sometimes slow them down. Their intention is usually to smooth over change, to become invisible. There are two important issues I will consider in relation to this. First, there is a shift in the agency of the user-subject of AR media in the sense that AR supplies a way to modify our experience of urban space, albeit in a rather limited way. We are offered the ability to return to a view of pre-quake Christchurch at any time. The platform allows us to reinstate an image of the old built environment in three dimensions on a screen while positioned in real space. In this way, it gives the sense that we can continue to engage with the place and its history, despite its physical absence. High Street Stories’ AR interface encourages users to experience urban space as part of what J. MacGregor Wise terms the ‘clickable world’ of new media, that “responsive and information-filled” world (159) that is constantly vying for our attention, and which tends to re-shape the relationship between agency and forms of control through the ever-increasing demands of networked communication. In short, having lost much of our city, we are offered a measure of control to re-live or reimagine it via the clickable world, but that control operates within the affordances and limitations of mobile and network technologies, and thus also imposes demands upon the user’s attention and upon their capacity to act in ways contrary to those pushed by the user’s device. To the extent that High Street Stories prioritises our interaction with content as an array of choices within given user interfaces, it supports Manovich’s claim that in new media often the “database … is given material existence, while narrative … is dematerialized” (89). A second, related issue, is the way in which High Street Stories flattens historical and temporal differences amongst the narratives it holds. Both the AR interface and the website situate the diverse histories it tells in a continuous virtual space. The interface tends to obscure the historical relationships between the many micro-narratives that make up the project, since it emphasizes their ‘equivalence’ as stories for the user to choose from and explore, as dots on a map and as database records that can be retrieved and displayed in a variety of ways. This again emphasises the capacity of database forms to offer different ways to access and interact with content (particularly the content’s spatial distribution), rather than emphasizing their historical specificity. As Wise comments, “Augmented reality systems seek to overlay the world with information attached to people, places, and objects. Though the goal is to add to experience, the danger is that the information itself stands in for the object (just as data selves take priority over physical selves)” (161). [Slide 7] Another somewhat similar project that has been developed more recently is Sound Sky, a “contributory art project” based on the Roundware software developed by US sound artist Halsey Burgund and others. Sound Sky is presented on its website as “an invisible layer of memories, stories, secrets and discoverable futures within Christchurch”. It enables location-based recording and playback of audio, some of which may be narratives, but many of which, from what I’ve listened to, are fragments, conversations, and recordings of noise. It is a wonderful project precisely because it is sound-based, and because it uses the listener’s location to determine the stories recorded nearby that will be played back, and, insofar as it is possible with two channels, the ‘direction’ of the story. A multichannel installation played Sound Sky, with more precise spatial reproduction and an algorithmic selection of recordings, at the Auricle Sonic Arts Gallery in October 2014. The key difference here is that users are not given a selection from a list or a search function to listen to stories, as this is determined by location. In this sense, groups of stories will tend to build up around locations, becoming denser as more stories are added. Story and place are correlated. Nonetheless, like CityViewAR and High Street Stories, while Sound Sky provides unique experience and insight into the interaction between place and sound, it tends to flatten the temporal element of the recordings. Lastly, I’d like to consider a rather different type of project, one that brings together a number of contributing databases containing text narratives, images, video and other media relating to the earthquakes. This project is the CEISMIC Canterbury Earthquakes Digital Archive (“UC CEISMIC Canterbury Earthquake Digital Archive”), which I have been personally involved in since 2012, a few months after it began. I will not go into much of the background to the project, but will touch on the points most relevant to the present discussion of narrative and database forms in the context of a digital archive. Unlike the High Street Stories or Sound Sky, CEISMIC is comprised of many sub-projects of varying natures. The CEISMIC website, therefore, is essentially a search index that brings together metadata about this variety of earthquakerelated resources. This search function is enabled by DigitalNZ, a unit within the National Library of New Zealand, who are another key partner in CEISMIC. In this sense, CEISMIC is an index of multiple databases of content, and in general it displays the metadata that was most easily extracted and combined. As you may know, crosswalking multiple datasets is often very difficult and although CEISMIC does this successfully in many areas, there are also gaps and issues that haven’t been overcome. The implications of this are that while CEISMIC provides fantastic assistance for finding content across more than 90,000 records, the activity of searching and filtering via search facets is relatively distant from the full text content itself. There is a strong focus on stories, but as far as I know they are all stored in databases of one form or another, and, to varying degrees can be explored via interfaces that either emphasise their ‘narrative’ or their ‘database’ aspects. I’ll give one example: QuakeStories, created by our Ministry for Culture and Heritage, is one key sub-project contributing to CEISMIC. It has collected stories of people’s earthquake experiences, and in many cases images too. Although there are both narrative aspects and database aspects involved, as with High Street Stories we are presented with many stories to explore. However, a key difference is that QuakeStories employs little of the usual database-type ways of accessing content. Users do have the ability to browse and search, but this functionality is de-emphasised in favour of simply browsing page by page through stories, starting with whichever one is profiled on the home page. Although the majority of stories are geo-located, maps are only used on each individual story page, rather than by providing a distant overview of the spatial distribution of all stories. Among Manovich’s conclusions about the relationship between database and narrative is the suggestion that we want to bridge this gap, we want a kind of “new media narrative” that can “take into account the fact that its elements are organized in a database” (94). While Manovich argues the answer is to follow the example of avant-garde film, Katherine Hayles has considered this question in the context of object-oriented databases that can model events more sensitively than relational databases (Hayles, in Packer and Wiley 20). The University of Canterbury’s particular contribution to the CEISMIC project is QuakeStudies, an earthquake research repository that uses just such a ‘object-oriented’ database, and employs a data ontology that includes events, people, and places. Although it goes some way to try and model events in time, it is limited, not least because of the unending amount of work that generating such metadata creates for curators or administrators. Nonetheless, object-oriented models and semantic web technologies do offer data structures that we might consider more similar to narrative and that allow better expression of complex or nuanced relationships such as the relationship between a person and an event. In all these examples, a common thread is the suitability of database forms for presenting space, and narrative for presenting time. This is not at all a new observation, but I think it has interesting implications for the post-earthquake environment in Christchurch at present. The key difference is that unlike narratives, databases do not need represent a single point of view, or a limited number of point of views to be coherent objects of their type. [Slide 10] Given the need to re-imagine urban space and the way in which spaces are keenly involved in the production of social relations, I conclude that we’re seeing lots of interesting digital projects because database as cultural form appears better suited to communicate in certain ways in this situation. In particular, digital media has been prominent in PR for the Central City Blueprint and for particular building developments. However, I think digital media and the database form are still potentially very problematic in terms of their influence on user agency and their tendency to become a substitute for material interactions in some instances. I also speculate whether, in the post-disaster context, database forms appeal ideologically and politically precisely because they can simply aggregate multiple points of view, or adopt points of view like the ‘fly through’ or ‘fly over’, that doesn’t correspond to a mundane human perspective. This is a possibility that remains for me to investigate via comparison with other types of natural disaster or social upheaval. [Final slide] Works Cited “Augmented Reality For Glass » CityViewAR for Glass.” n.d. Web. Bauman, Zygmunt. Liquid Modernity. Cambridge : Malden, MA: Polity Press ; Blackwell, 2000. Print. “FESTA - The Arcades Project.” n.d. Web. < http://festa.org.nz/arcades/> Henning, Michelle. “Digital Encounters: Mythical Pasts and Electronic Presence.” The Photographic Image in Digital Culture. Ed. Martin Lister. London ; New York: Routledge, 1995. Print. “High Street Stories.” n.d. Web. < http://www.highstreetstories.co.nz/> Judd, Stephen. “The Enervation Precinct.” Once in a Lifetime: City-Building after Disaster in Christchurch. Christchurch: Freerange Press, 2014. 98–99. Print. Manovich, Lev. “Database as Symbolic Form.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 5.2 (1999): 80–99. Web. MBIE Quarterly Job-Matching Report - June 2014. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2014. Web. MBIE Quarterly Job-Matching Report - September 2014. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2014. Web. Packer, Jeremy, and Stephen B. Crofts Wiley, eds. Communication Matters: Materialist Approaches to Media, Mobility and Networks. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2012. Print. Reynolds, Ryan. “Desire for the Gap.” Axon Journal 5.1 (2015): n. pag. Web. “UC CEISMIC Canterbury Earthquake Digital Archive.” n.d. Web. <http://www.ceismic.org.nz/> Wise, J. MacGregor. “Attention and Assemblage in the Clickable World.” Communication Matters: Materialist Approaches to Media, Mobility and Networks. Ed. Jeremy Packer and Stephen B. Crofts Wiley. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2012. Print.

![You can the presentation here [Powerpoint, 1.01MB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005417570_1-0810139cfc2485ebcaf952e0ae8bb49a-300x300.png)