Reference list - Skin to Skin Contact

advertisement

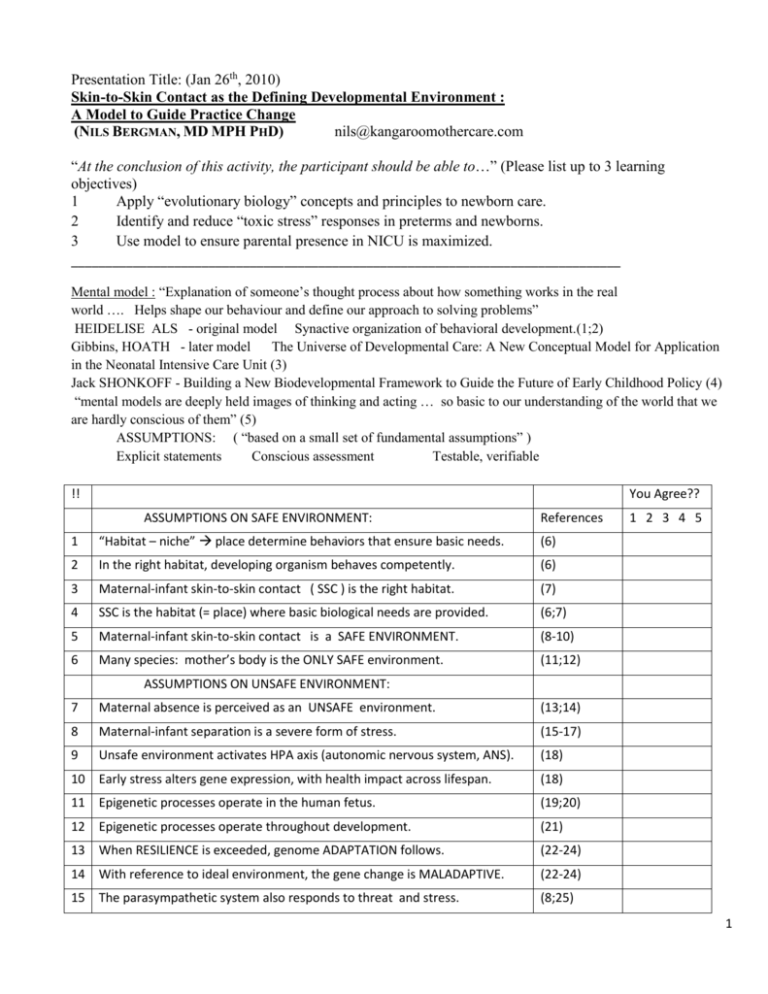

Presentation Title: (Jan 26th, 2010) Skin-to-Skin Contact as the Defining Developmental Environment : A Model to Guide Practice Change (NILS BERGMAN, MD MPH PHD) nils@kangaroomothercare.com “At the conclusion of this activity, the participant should be able to…” (Please list up to 3 learning objectives) 1 Apply “evolutionary biology” concepts and principles to newborn care. 2 Identify and reduce “toxic stress” responses in preterms and newborns. 3 Use model to ensure parental presence in NICU is maximized. ________________________________________________________________________________ Mental model : “Explanation of someone’s thought process about how something works in the real world …. Helps shape our behaviour and define our approach to solving problems” HEIDELISE ALS - original model Synactive organization of behavioral development.(1;2) Gibbins, HOATH - later model The Universe of Developmental Care: A New Conceptual Model for Application in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (3) Jack SHONKOFF - Building a New Biodevelopmental Framework to Guide the Future of Early Childhood Policy (4) “mental models are deeply held images of thinking and acting … so basic to our understanding of the world that we are hardly conscious of them” (5) ASSUMPTIONS: ( “based on a small set of fundamental assumptions” ) Explicit statements Conscious assessment Testable, verifiable !! You Agree?? ASSUMPTIONS ON SAFE ENVIRONMENT: References 1 “Habitat – niche” place determine behaviors that ensure basic needs. (6) 2 In the right habitat, developing organism behaves competently. (6) 3 Maternal-infant skin-to-skin contact ( SSC ) is the right habitat. (7) 4 SSC is the habitat (= place) where basic biological needs are provided. (6;7) 5 Maternal-infant skin-to-skin contact is a SAFE ENVIRONMENT. (8-10) 6 Many species: mother’s body is the ONLY SAFE environment. (11;12) 1 2 3 4 5 ASSUMPTIONS ON UNSAFE ENVIRONMENT: 7 Maternal absence is perceived as an UNSAFE environment. (13;14) 8 Maternal-infant separation is a severe form of stress. (15-17) 9 Unsafe environment activates HPA axis (autonomic nervous system, ANS). (18) 10 Early stress alters gene expression, with health impact across lifespan. (18) 11 Epigenetic processes operate in the human fetus. (19;20) 12 Epigenetic processes operate throughout development. (21) 13 When RESILIENCE is exceeded, genome ADAPTATION follows. (22-24) 14 With reference to ideal environment, the gene change is MALADAPTIVE. (22-24) 15 The parasympathetic system also responds to threat and stress. (8;25) 1 16 The ANS of a preterm or neonate differs from that of adults. (25) 17 The primary defense of a preterm or neonate is immobilization (25-27) 18 Threat response sequence: vigilance freeze dissociation (25;28) 19 Children are not “small immature adults” (25;28) 20 Newborns and infants are sensitive, and must still develop resilience. (25;28) 21 Sympathetic and parasympathetic hyper-activation harms the brain. (26;27) 22 Early toxic stress leads to neurological (mal)adaptation. (29) 23 Early adverse experience profoundly impacts resilience and development. (27;29) 24 Mother-Infant Interaction is the primary development determinant (30) PRELIMINARY CONCEPT: “PLACE MODEL” ASSUMPTIONS ON THE SKIN-TO-SKIN CONTACT ENVIRONMENT 25 The basic behavior choice depends on “Am I Safe?” (neuroception) (25;31) 26 SSC from birth STABILIZES, even low birth weight neonates. (31) 27 SEPARATION at birth leads to DYS-REGULATION in preterms. (31) 28 Skin-to-skin contact amygdala “frontal” PFOC APPROACH . (26;32;33) 29 SSC in neonates activates approach, separation leads to avoid orientation (34-36) 30 Separated neonates experience disturbances of sleep cycling. (37-40) 31 Separation causes ANS response patterns consistent with threat. Bergman ASSUMPTIONS ON DEVELOPMENTAL ENVIRONMENT 32 SSC promotes better sleep, brain maturation and neuro-protection. (41;42) 33 Newborns have all their senses developed, open and receptive. (Lind) 34 Maternal sensory environment “fires and wires” brain development. (15;43-46) 35 Skin-to-skin contact activate “safe” maternal-infant ANS exchanges (26;43;44) 36 Skin-to-skin is the foundation for physiological REGULATION. (26;43;44) 37 Skin-to-skin contact signals “emotional safety” brain develops. (26) 38 SSC SAFE ANS exchanges communication ATTACHMENT. (47;48) 39 Skin-to-skin contact INITIATES dual coding physical & mental health (47) 40 Infants need the “buffering protection of adult support”. (49) 41 “Relationships are the active ingredients of early experience.” (49) 42 Critical “needed neural processes” are wired from birth & onwards. (48;50-55) 43 SSC fired “needed neural processes” operate in the maternal brain also. (48;5254;56;57) (30) 44 Neurodevelopment requires the presence of mother (or parent). DEVELOPMENTAL ENVIRONMENTS MODEL IMPLICATIONS (4) Comment: references as above may not state the assumption formulated, but have been used to derive it. 2 “Approach to solving problems: 3. Uncompromising Mother’s (parental) presence is ABSOLUTE requirement. 4. Threatening Maternal-infant separation is primary cause of HARM. Reference List (1) Als H. Toward a Synactive Theory of Development: Promise for the Assessment and Support of Infant Individuality. Infant Mental health 1982;3(4):229-43. (2) Als H, Butler S. Newborn individualized developmental care and assessment program (NIDCAP) . Changing the furtue fior infants and families in intensive care nurseries. Early Childhood Services 2008;2(1):1-20. (3) Gibbins S, Hoath SB, Coughlin M, Gibbins A, Franck L. The universe of developmental care: a new conceptual model for application in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care 2008 June;8(3):141-7. (4) Shonkoff JP. Building a new biodevelopmental framework to guide the future of early childhood policy. Child Dev 2010 January;81(1):357-67. 3 (5) Kuhn TS. The structure of scientific resolutions. International Encyclopedia of unified science 2008. (6) Alberts JR. Learning as adaptation of the infant. Acta Paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992) Supplement 1994 June;397:77-85. (7) Bergman NJ, Jurisoo LA. The 'kangaroo-method' for treating low birth weight babies in a developing country. Trop Doct 1994 April;24(2):57-60. (8) Porges SW. Love: an emergent property of the mammalian autonomic nervous system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998 November;23(8):837-61. (9) Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. Int J Psychophysiol 2001 October;42(2):123-46. (10) Rey ES, Martinez HB. Manejo rational de nino premature. Curso de medicina fetal y neonatal, Bogota, Colombia 1983;(17 March):137-51. (11) Panksepp J. Affective neuroscience. Oxford Univarsity Press; 1998. (12) Nelson EE, Panksepp J. Brain Substrates of infant-mother attachment: Contributions of opioids, oxytocin and norepinephrine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1998;22(3):437-52. (13) Harlow HF, Suomi SJ. Social Recovery by Isolation-Reared Monkeys. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1971 July 1;68(7):1534-8. (14) Ziabreva I, Poeggel G, Schnabel R, Braun K. Separation-induced receptor changes in the hippocampus and amygdala of Octodon degus: influence of maternal vocalizations. J Neurosci 2003 June 15;23(12):5329-36. (15) Hofer MA. Early relationships as regulators of infant physiology and behaviour. Acta Paediatr 1994;Suppl 397:9-18. (16) Poletto R, Siegford JM, Steibel JP, Coussens PM, Zanella AJ. Investigation of changes in global gene expression in the frontal cortex of early-weaned abd socially isolated piglets using microarray and quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Brain Res 2006;1068:7-15. (17) Rosenblum LA, Andrews MW. Influences of environmental demand on maternal behaviour and infant development. Acta Paediatr 1994;Suppl 397:57-63. (18) Meaney MJ, Szyf M. Maternal care as a model for experience-dependent chromatin plasticity? Trends in Neurosciences 2005;28(9):456-63. (19) Barker DJ. In utero programming of chronic disease. Clinical Science (London, England: 1979) 1998 August;95(2):115-28. (20) Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsen T, Osmond C. Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol 2002 December;31(6):1235-9. (21) Gluckman P, Hanson M. The Fetal Matrix Evolution, Development and Disease. The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge; 2005. (22) Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: and evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Dev 1991 August;62(4):647-70. (23) Ganzel BL, Morris PA, Wethington E. Allostasis and the human brain: Integrating models of stress from the social and life sciences. Psychological Review 2010 January;117(1):134-74. (24) Lozoff B, Brittenham GM, Trause MA, Kennell JH, Klaus MH. The mother-newborn relationship: limits of adaptability. J Pediatr 1977 July;91(1):1-12. 4 (25) Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biological Psychology 2007 February;74(2):116-43. (26) Schore AN. Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal 2001;22(1-2):7-66. (27) Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal 2001;22(1-2):201-69. (28) Perry BD, Pollard RA, Blakely TL, Baker WL, Vigilante D. Childhood trauma, the neurobiology of adaptation and "usedependent" development of the brain. How"states" become "traits". Infant Mental health 1995;16(4):271-91. (29) Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP. Developmental neurobiology of childhood stress and trauma. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2002 June;25(2):397-426. (30) Swain JE, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Strathearn L. Brain basis of early parentinfant interactions: psychology, physiology, and in vivo functional neuroimaging studies. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry 2007 March;48(3/4):262-87. (31) Bergman NJ, Linley LL, Fawcus SR. Randomized controlled trial of skin-to-skin contact from birth versus conventional incubator for physiological stabilization in 1200- to 2199-gram newborns. Acta Paediatr 2004 June;93(6):779-85. (32) Amodio DM, Master SL, Yee CM, Taylor SE. Neurocognitive components of the behavioral inhibition and activation systems: Implications for theories of self-regulation. Psychophysiology 2008;45:11-1. (33) Schore AN. Attachment and the regulation of the right brain. Attach Hum Dev 2000 April;2(1):23-47. (34) Coan JA. A capability model of individual differences in frontal EEG asymmetry. Biological Psychology 2005;72(2):198207. (35) Jones NA, McFall BA, Diego MA. Patterns of brain electrical activity in infants of depressed mothers who breastfeed and bottle feed: the mediating role of infant temperament. Biological Psychology 2004 October;67(1/2):103-24. (36) Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS, Kim S. Depression, anxiety, and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: a meta-analytic review. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology 2006 November;115(4):715-29. (37) Kinkead R, Montandon G, Bairam A, Lajeunesse Y, Horner R. Neonatal maternal separation disrupts regulation of sleep and breathing in adult male rats. Sleep 2009 December 1;32(12):1611-20. (38) Ludington-Hoe Sm. Preterm skin contact effects on electrophysiologic sleep. Research ShowCASE [4 April], 192. 2003. Ref Type: Abstract (39) Mosko S, McKenna J, Dickel M, Hunt L. Parent-infant cosleeping: the appropriate context for the study of infant sleep and implications for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) research. Journal Of Behavioral Medicine 1993 December;16(6):589-610. (40) Peirano P, Algarin C, Uauy R. Sleep-wake states and their regulatory mechanisms throughout early human development. Journal of Pediatrics 2003 October 2;143(4):S70-S79. (41) Ludington-Hoe Sm, Johnson MW, Morgan K, Lewis T, Gutman J, Wilson D et al. Neurophysiologic assessment of neonatal sleep organization: Preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contant with preterm infants. Pediatrics 2006 May;112(5):e909-e923. (42) Scher MS, Ludington-Hoe S, Kaffashi F, Johnson MW, Holditch_davis D, Loparo KA. Neurophysiologic assessment of brain maturation after an 8-week trail of skin-to-skin contact on preterm infants. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120(10):1812-8. (43) Hofer MA. Motherless child. Sciences 1992 July;32(4):12. 5 (44) Hofer MA. The psychobiology of early attachment. Clinical Neuroscience Research 2005;15(2):84-7. (45) Shatz CJ. The developing brain. Sci Am 1992 September;267(3):60-7. (46) White RD. Mothers' arms--the past and future locus of neonatal care? Clin Perinatol 2004 June;31(2):383-7, ix. (47) Greenspan SI, Shanker SG, Phil D. The First Idea: How symbols, language, and intelligence evolved from our primate ancestors to modern humans. 1st ed. Cambridge: Da Capo Press; 2006. (48) Lenzi D, Trentini C, Pantano P, Macaluso E, Iacoboni M, Lenzi GL et al. Neural basis of maternal communication and emotional expression processing during infant preverbal stage. Cerebral Cortex (New York, N Y : 1991) 2009 May 11;19(5):1124-33. (49) National Research Council Institute of medicine. From Neurons to Neighborhoods. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2000. (50) Leng G, Meddle SL, Douglas AJ. Oxytocin and the maternal brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008 December;8(6):731-4. (51) Bosch OJ, Meddle SL, Beiderbeck DI, Douglas AJ, Neumann ID. Brain oxytocin correlates with maternal aggression: link to anxiety. J Neurosci 2005 July;%20;25(29):6807-15. (52) Browne JV. Early relationship environments: physiology of skin-to-skin contact for parents and their preterm infants. Clin Perinatol 2004 June;31(2):287-98, vii. (53) Graven SN. Early neurosensory visual development of the fetus and newborn. Clin Perinatol 2004 June;31(2):199-216, v. (54) McNeilly AS, Robinson ICAF, Houston MJ, Howie PW. Release of oxytocin and prolactin in response to suckling. British Medical Journal (Clin Res Ed) 1983 January 22;286(6361):257. (55) Uvnas-Moberg K, Widstrom AM, Marchini G, Winberg J. Release of GI hormones in mother and infant by sensory stimulation. Acta Paediatr Scand 1987 November;76(6):851-60. (56) Ross HE, Young LJ. Oxytocin and the neural mechanisms regulating social cognition and affiliative behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol 2009 October;30(4):534-47. (57) Bigelow AE, Littlejohn M, Bergman N, McDonald C. The relation between early mother-infant skin-to-skin contact and later maternal sensitivity in South African mothers of low birth weight infants. Infant Mental Health Journal 2010 May;31(3):358-77. 6