Syllabus - Filippo Rebessi

advertisement

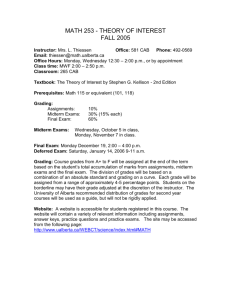

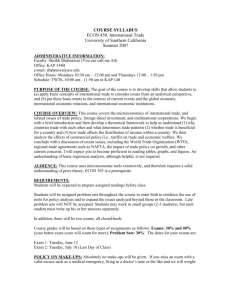

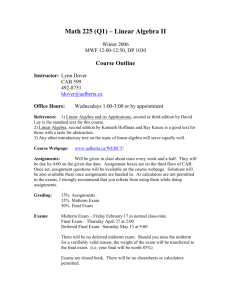

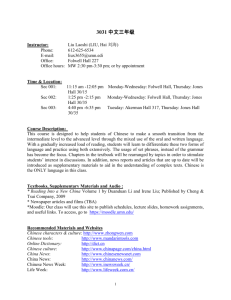

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA Spring 2014 ECONOMICS 4401: INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS INSTRUCTOR: Filippo Rebessi OFFICE: Hanson Hall 3-153 E-MAIL: rebes001@umn.edu CLASS TIME: M/W 4:00PM – 5:15PM ROOM: Blegen 245 OFFICE HRS: M/W 9:30AM-10:30AM CLASS WEBSITE: http://www.filipporebessi.com Econ 4401 satisfies the Global Perspectives Theme requirement of Liberal Education at the University of Minnesota. The course, and most or all of the material covered in the course, focuses on the world beyond the United States. Econ 4401 is a course on international economics. It is geared to economics non-majors; students from other disciplines who wish to have an understanding of the functioning of the world economy in terms of the movement of goods and capital across national boundaries. It includes theories and applications of international trade and international finance; as well as government policies to regulate this exchange. It is not a course devoted to studying U.S. trade and its international transfers of capital. Since the U.S. is the largest trader in the world, both in terms of goods as well as finance, it is important to understand its role in world international transactions. It is also important to bear in mind the role of other countries like U.K., Spain, Portugal, France, Holland, Japan, China, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Hong Kong, etc. who have been front runners in goods trade and worldwide financial flows, and have influenced economic indicators of many nations. The course is split into two parts: International Trade, which takes up the first half, and International Finance, which is studied in the second half (normally after the midterm exam). The first part of the course, International Trade, studies the theories of trade; the Mercantilist model, the Classical models, the Neo-Classical model, and the Modern theories including the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of trade. The origin of the theories deals with issues of concern in worldwide trade at the different time periods. The Mercantilist model, Classical models of trade by Adam Smith, David Hume, David Ricardo, and the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of trade will be examined. The course explains the theoretical underpinnings of trade restrictions like tariffs, quotas, subsidies, export taxes, and others. Countries have different reasons for imposing trade restrictions, and the course includes many case studies to see the causes and effects of trade restrictions in these countries. We specifically study the outcome of the US-Japan auto trade in the early 1980s with reference to effects of Japan’s Voluntary Export Restraint on cars exported to the U.S. Other case studies include the effects of import tariffs on Japanese trucks in the early 1980s, the protected computer industry in Brazil (from 1977-1990), agricultural subsidies under the Doha Round (for EU, US, China, Brazil, India, and others), sugar subsidies by the EU and effects on Brazil, various WTO disputes, the Boeing-Airbus ongoing dispute over subsidies received, trade liberalization in Mexico and New Zealand, a study of the effects of protection instruments on domestic prices in countries, etc.. The policies and efficacies of GATT and WTO in reducing trade restrictions are analyzed along with the debate on free trade. Arguments for and against protection are studied, and some case studies are presented. Other topics in trade include effects of labor and capital mobility across nations, effects of trade liberalization and movement towards free trade, and the ongoing phenomena of regional integration with increased formation of free trade areas. In this part of the course, students are exposed to the effects of labor migration and capital mobility across nations. The best way to explain the effects is to give examples of historical migrations and the effects on the recipient and parent countries. We discuss the labor migrations from European countries into the US in the 1700s and 1800s, the “Brain Drain” issue (and effects) of people migrating from less developed countries like India and China to the US and Europe, the effects of capital mobility as evidenced by the Asian financial crisis in late 1990s, the role of capital mobility in the formation of “Maquiladoras” in Mexico, and in examples like Toyota and Honda setting up manufacturing plants in the US to get around trade restrictions on cars from Japan. 1 Trade liberalization and Regional Integration are examined; this includes the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and the formation of the European Economic Community. We study the formation of the EU in its various stages and the subsequent trade liberalization. Other agreements like NAFTA, ASEAN, SACU, MERCOSUR, CER between Australia and New Zealand, and others are discussed in order to see the benefits and disadvantages to people of these countries. The second part of the course, International Finance, covers basic concepts, tools and facts needed to understand the functioning of the global economy and international financial markets. It includes studies of all aspects of international finance and financial policy; it highlights balance of payments; international financial markets; exchange rate determination; international monetary system; international investment and capital flows; financial management of multinational firms and open economy macroeconomic policy. The workings of the foreign exchange markets are explained where residents of different countries interact by trading money and goods with each other for current and future delivery. Interdependencies in the world are shown by highlighting linkages between countries’ exchange rates, policies, and world events. Foreign exchange markets today exhibit effects of government policies- exchange rate policies, monetary and fiscal policies, trade agreements and talks, political systems of countries, and a host of other events. Balance of payments accounts provide a summary of a nation's trade with the rest of the world. The theories of the balance of payments explain why some countries run deficits and others run surpluses, and why currencies appreciate and depreciate. Prices, interest rates and exchange rates explain that exchange rates are dependent on prevailing and expected world and country prices and on current and expected foreign and domestic interest rates. Various theories and empirical results are discussed to show the relationships. International monetary systems study arrangements existing between countries regarding exchange rates and money flows. This includes a study of the gold standard, the inter-war period, the Bretton-Woods system, the transition years, and the current regime of floating exchange rates. The workings of the IMF and the World Bank are analyzed in the context of world relationships. This section on international finance emphasizes monetary and financial interrelationships in the world by showing that any action taken by one country with respect to its international position affects other trading partners as well; who in turn, base their policies on current and expected policies of other nations. Every topic in the course is illustrated by some global event and its effects. Case studies may include: Doha Round of Trade Talks; role of agricultural subsidies World trade in oil; oil prices; major suppliers and buyers of oil Regional Integration and effect on members and non-members Effects of NAFTA; EU; others Piracy, terrorism, and world trade Argentina’s economic crisis in 2002 following the collapse of the fixed exchange rate. U.S. trade deficit over the years and its effects, including a discussion of whether it is “good” or “bad”; and the discussion of China’s current trade surplus Role of China (and its undervalued currency) in current global imbalances, and a call for revaluation of the yuan Dollarization in Ecuador and its effects International capital mobility (cuurent) and its role in affecting exchange rates Mexico’s peso crisis of 1994 Hyperinflations in Germany (1923), Hungary (1946), Argentina (1983), Zimbabwe (2001, 2003, 2005) Consequences of Foreign Reserve accumulation in emerging markets (2008 onwards) Effects of a currency union- the case of the EU and the Euro Sovereign default- example of Iceland in 2008-09 and Greece 2010 (and its bailout) Current economic slowdown and its effect on world trade Current world trading patterns compared to patterns 20 years ago The course either (1) focuses in depth upon a particular country, culture, or region or some aspect thereof; (2) addresses a particular issue, problem, or phenomenon with respect to two or more countries, cultures, or regions; or (3) examines global affairs through a comparative framework. 2 The principal objective of the course is to study the international economic interdependencies in the world today. The course does not focus on any specific country or region. It does however address several issues that involve trade among nations, including free trade, trade restrictions, protection, regional integration, formation of free trade areas, mobility of labor and capital, and linkages arising from exchange rate movements, balance of payments scenarios, and various monetary standards. All these issues are discussed with reference to specific countries and country groups, but the focus is on the issue and its effects on all concerned. Trade restrictions are very prevalent in most countries and lead to problems in the imposing countries as well as in their trading and non-trading partners. For example, EU policy on banana trade has vast implications for the banana producers in the Caribbean and Latin America. Another example is the Factor Price Equalization theorem, which states that free trade between countries leads to equality of wages in both countries. We study the case of outsourcing and wages in US and India in the service sector, and the wages in China and other Southeast Asian nations in the textile sector. In other cases, wage equalization may not happen due to government intervention in the labor market, as is the case in France and Spain. We also study the international economic interdependencies in the world today relating to the effects of international capital mobility. We study the costs and benefits of financial globalization, major policy issues like fixed versus flexible exchange rates, role of government monetary or fiscal policies in manipulating these exchange rates, role of online foreign exchange services, common currencies, and the causes and effects of financial crises. The course does not focus on any specific country or region. It does however, address several issues that involve capital mobility among nations. All issues and effects are examined from multiple viewpoints- from the points of view of domestic and foreign consumers, producers, governments, institutions; we also study the effects of free and restricted capital mobility on interest rates, foreign direct investment, balance of payments, prices, wages, employment, production, growth, volume of trade and composition of trade, and international debt. COUNTRY REPORT Students are required to write a paper on a country of their choice (Not the U.S.). This is to encourage students to delve into international affairs of a particular country, find out the trade issues and how the country deals with them; how the country deals with issues of international capital mobility, and how it responds to changes in world issues. Details further on. Students discuss and reflect on the implications of issues raised by the course material for the international community, the United States, and/or for their own lives. The course material emphasizes the implications of trade in goods and financial globalization on all affected parties in all countries, including on the students themselves. Particular emphasis is placed on the fact that trade and capital mobility leads to winners and losers, and these groups may be in the same or different country. For example, a tariff will lead to higher prices for imports, adversely affecting domestic consumers and foreign producers and exporters, but favorably affecting domestic producers and the domestic government who collects the tariff revenue. A devaluation of a currency will lead to relatively cheaper exports, which in turn may lead to rising exports or falling exports (depending on demand from trading partners). An influx of capital through Foreign Direct Investment can have a myriad of effects- a fall in interest rates, increased growth in the sectors using the additional capital, the transfer of technology, but it may lead to losses if the capital is withdrawn (as happened in the Asian crisis). These effects can impact consumers and domestic producers adversely or favorably depending on a host of factors including how the capital was used, what industry it was used in, profits being repatriated or being re-invested, and so on. Students are asked to explicitly detail the outcome of all international transactions on various groups (in class activities, homework assignments, and exams) – on domestic and foreign consumers, producers, governments, institutions; and on economic variables like prices, wages, employment, volume of trade, composition of trade, trading partners, exchange rates, balance of payments, capital mobility, and on income distribution across nations. We supplement this course by sharing current international trade and financial events with you, the students. These articles are from the New York Times, the Economist, Foreign Policy, Foreign Affairs, various Federal Reserve Bank publications, World Bank and IMF publications, etc…We want you to understand that course topics are applicable to real-life events. We are convinced that you should be familiar with trade and financial events as they occur in the world around us. ************************************************************************************************************ 3 TEXTBOOK: INTERNATIONAL ECONOMICS by Steven Husted and Michael Melvin, 9th Edition READINGS: I will assign course readings every week and post them on the class webpage. We cover the readings in class and you are expected to do the reading before that. Readings will be selected from economic reviews, journals and news. PREREQUISITES: Econ 1101 and Econ 1102. This class is for solely for students who are not majoring in economics COURSE TOPICS: International Trade (Weeks 1-7) 1. Introduction to International Trade and Trade Facts (Chapter 1) 2. Tools of Analysis for International Trade Models (Chapter 2) 3. Classical Model of International Trade (Chapter 3) 4. Heckscher-Ohlin Model (Chapter 4) 5. Tests of Trade Models (Chapter 5) 6. Trade Restrictions and Protection (Chapters 6, 7) 7. Commercial Policy: History and Practice (Chapter 8) 8. Preferential Trade Arrangements (Chapter 9) International Finance (Weeks 8-15) 9. The Balance of Payments (Chapter 11) 10. Foreign-Exchange Market (Chapters 12) 11. International Monetary Systems (Chapter 13) 12. Exchange Rates in the Short Run (Chapter 14) 13. Exchange Rates in the Long Run (Chapter 15) 14. Theories of the Current Account (Chapters 16) 15 Open-Economy Macroeconomics (Chapter 17) 16. International Banking, Debt and Risk (Chapter 19) HOMEWORK ASSIGNMENTS: There will be 4 homework assignments; the tentative due dates are outlined below, official due dates when the homework is posted online on the class webpage. Written answers to homework assignments must be typed; this is in accordance with departmental policy. Graphs and numerical computations need not be typed, but should be legible. You may discuss homework with classmates but you must write up your answers in your own words. Identical answers are not acceptable. Some homework assignments will require you to use a spreadsheet (like MS Excel) to analyze data. Assignments are due at the beginning of the class on the due date. If you cannot make it to class, make sure the assignment reaches me on time (on time means lecture time on the due date). No late assignment will be accepted. Only documented special circumstances (e.g. illness, family emergency) will exempt you from this rule. COUNTRY STUDY: Each group of students must choose a country and complete a 7 pages minimum report on that country (typed in Times New Roman, 12pt, double spaced, 1 inch margin). Countries will be assigned in class after we form groups. Objective: To present clear and concise information about important aspects and features of international trade and finance of your chosen country. You should organize your Report around the following questions: 1) What is the major international trade/finance issue related to this country’s current (or past) economic situation? 2) What change in policy would you recommend to this country’s government to improve the situation? Why? Your report should start with a concise answer to both these questions. (max length: 0.5 page) You should then have an introduction in which you document the level of this country’s institutional and economic development and the importance of international trade/finance in this country over time. The World Bank and IMF’s Databases are a good source of data for this section. We will talk more extensively about sources for data and information 4 for your report in class. (min length: 2.5 pages) You will then offer a detailed description of the issue you have chosen to analyze; you are expected to bring economic arguments and data to motivate why this issue is an important one for the country’s economy. (min length: 2.5 pages) Finally, you will present your policy recommendation and defend it (min length: 1.5 pages) You can and are encouraged to use tables, charts and graphs in your Report. Cite every source you use; a good (and easily accessible) bibliography format is the one used by the Journal of Political Economy. Examples of Country studies from Fall 2013 will be posted on the class webpage. Each group HAS to turn in a Country Study Proposal by Wednesday, February 19 th, in class. The proposal includes: the chosen Country, a brief description of the International Economics issue of the Country and an informal motivationyou’re your choice. For the presentations, you are required to prepare slides that synthesize and convince the audience of the key points of your Report. This is worth 1/3 of the Country Study’s grade: I expect your presentation to be professional; please don’t exceed the time you are given and be ready to answer questions from the audience. Your presentation should include one initial slide with your country issue and a preview of your policy answer. You should then have one slide with some key economic facts for the Country you studied and about two slides that illustrate the importance of the selected issue. Finally, one or two slides should be dedicated to your suggested policy and its consequences. We will talk more about the presentation format in class. Examples of Country studies’ presentations from Fall 2013 will be posted on the class webpage EXAMS: MIDTERM EXAM FINAL EXAM (not cumulative) A short review may be given before the midterm and final exams. Both the midterm and the final are closed book exams. GRADING POLICY: The final grade is determined as follows: Homework Country Study Paper Presentation TOTAL Midterm Final 20% (5% each) (20%) (10%) 30% 25% 25% The numerical course grade will be converted to a letter grade according to the following scale 92-100 90-91 88-89 82-87 80-81 78-79 72-77 70-71 68-69 60-67 59 and below A AB+ B BC+ C CD+ D F RULES: 1. Make up’s are not allowed for the midterm exam under any circumstances, except in medical emergencies, where a doctor’s note is required. 5 2. Make up’s are possible for the final exam only if the student has another exam scheduled at the same time, or has three exams within a 16 hour period. This should be pre-arranged with the instructor. We can discuss an alternative exam time. 3. Incomplete grade: A low class standing is not a valid reason for an I grade. An I grade is given only in exceptional circumstances like hospitalization or family emergencies; and an arrangement must be worked out between the student and instructor before the final exam. Written proof of emergencies is required. Generally, an I grade can be given before the midterm exam. You have one year to make up an I; and must repeat the course in its entirety. IMPORTANT INFORMATION: This syllabus and other additional material (homework assignments, resource links, announcements etc...) will be available on the class website. Link(s) will be provided in class TENTATIVE SCHEDULE Week1 – (lecture: 1/22): Classes begin; Groups for the Country Study are formed Week2 – (lecture: 1/27 & 1/29): HW I posted on class webpage Week3 – (lecture: 2/3 & 2/5): Week4 – (lecture: 2/10 & 2/12): 2/12: HW I due; HW II posted on class webpage Week5 – (lecture: 2/17 & 2/19): 2/19: Country Study Proposal Due Week6 – (lecture: 2/24 & 2/26): 2/26: HW II due Week7 – (lecture: 3/3 & 3/5): Week8 – (lecture: 3/10 & 3/12): 3/10: Midterm Exam (during class time) Week9 – (no lecture): Spring Break Week10 – (lecture: 3/24 & 3/26): HW III posted on class webpage Week11 – (lecture: 3/31 & 4/2): Week12 – (lecture: 4/7 & 4/9): 4/9: HW III due; HW IV posted on class webpage Week13 – (lecture: 4/11 & 4/16): Week14: – (lecture: 4/18 & 4/23): 4/23: Country Study Report due Week15: – (lecture: 4/28 & 4/30): 4/30: HW IV due Week16: - (lecture: 5/5 & 5/7): Country Study Presentations Week 17: - (exams week): 5/12: Final Exam (4:00 PM) ************************************************************************************************************ IMPORTANT DATES MIDTERM EXAM: 4:00 PM, Wednesday, March 12th FINAL EXAM: 4:00 PM, Monday, May 12th (see also http://onestop.umn.edu/calendars/final_exams/) 6 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS -- PROCEDURES AND POLICIES 2013-2014 4-101 Hanson Hall (612-625-6353) CLASS ASSIGNMENTS: Written answers to homework assignments must be typed; Graphs and numerical work need not be typed, but should be legible. COURSE PREREQUISITES: Students are expected to have successfully completed all prerequisites prior to taking an Economics course. DISABLED STUDENTS: Reasonable accommodations will be provided for all students with documented disabilities (by the OSD). Contact the instructor at the beginning of the semester to work out details. This information will be kept confidential. DROPPING A CLASS: Termination of attendance alone is not sufficient to drop a class. You must notify the Registrar’s office. Please contact your academic (college) adviser for details on this process and pay attention to University deadlines for add/drop. INCOMPLETE GRADE: Low class standing is not a valid reason for an Incomplete grade. An I is given only in exceptional circumstances like family emergencies or hospitalization; arrangements must be worked out between the student and instructor before the final exam. We require written proof of emergencies. Details about I grades and how to make it up -in the Economics Undergraduate Handbook. MAKE-UP EXAMS: Make up exams are possible for the final exam only if the student has another exam scheduled at the same time, or has three exams within a 16 hour period. This should be pre-arranged with the instructor at least three weeks before the final exam. Make up final exams may also be possible for documented medical emergencies. SCHOLASTIC DISHONESTY: "The College of Liberal Arts defines scholastic dishonesty broadly as any act by a student that misrepresents the student's own academic work or that compromises the academic work of another. Examples include cheating on assignments or exams, plagiarizing (misrepresenting as one's own anything done by another), unauthorized collaboration on assignments or exams, or sabotaging another student's work". The University Student Conduct Code defines scholastic dishonesty as “Submission of false records of academic achievement; cheating on assignments or examinations; plagiarizing; altering, forging, or misusing a University academic record; taking, acquiring, or using text materials without faculty permission; acting alone or in cooperation with another to falsify records or to obtain dishonestly grades, honors, awards, or professional endorsement.” Penalties for scholastic dishonesty of any kind in any course will entail an "F" for the particular assignment/exam or the course. Please check this website for information on Student Academic Misconduct -http://www1.umn.edu/oscai/integrity/student/index.html STUDENT CONDUCT AND CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR: Students are expected to contribute to a calm, productive, and learning environment. Please check this website for information on student classroom behavior issues: http://www1.umn.edu/regents/policies/academic/Student_Conduct_Code.html .Check the Student Conduct Code to find out what is expected of you. STUDY ABROAD IN ECONOMICS: The Department encourages you to undertake Study Abroad. There are many courses in foreign countries that can satisfy some economics major, minor, or Liberal Education requirements. For more information, please contact our Undergraduate Advisor, Ms. Madhu Bhat, or the University’s Learning Abroad Center at http://www.umabroad.umn.edu/ UNDERGRADUATE ADVISER: Contact the Undergraduate Adviser if you wish to sign up for an Economics major or minor or to get information about institutions of higher study. Your APAS form will list your progress toward an Economics degree. Adviser: Ms. Madhu Bhat ( econugra@econ.umn.edu ) Office: 4-100 Hanson Hall (office hours are posted on the door) Phone number: 612-625-5893 UNDERGRADUATE HANDBOOK: Available on the Internet at: http://www.econ.umn.edu/ Click on Undergraduate Programs. Registration policies are listed in the University Course Schedules and College Bulletins. COMPLAINTS OR CONCERNS ABOUT COURSES: All course grades are subject to department review. Please contact your instructor or TA if you have any complaints/concerns about the course. If your concerns are not resolved after talking with your instructor, you can contact: Professor Simran Sahi, Director of Undergraduate Studies (Phone): 612-625-6353 and E-mail: ssahi@umn.edu . 7