LIN 5301 Final - Question 2

advertisement

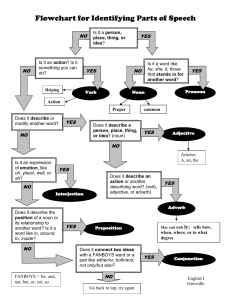

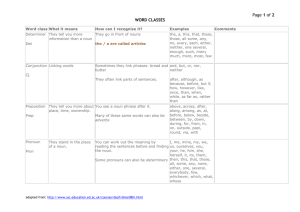

2.1. Morpheme vs. Allomorph: Similarities and Dissimilarities. A morpheme is the smallest unit of language that carries information about meaning or function. The word builder, for example, consists of two morphemes: build (with the meaning ‘construct’) and –er (which indicates that the entire word functions as a noun with the meaning ‘one who builds’). Some words consist of a single morpheme. For example, the word think cannot be divided into smaller parts that carry information about its meaning or function. Such words are said to be simple words and are distinguished from complex words, which contain two or more morphemes examples of each are couples, made up of the morpheme couple and the plural ‘s’, and workers, made up of the morpheme work, suffix –er, and the plural ‘s’. Allomorphs, on the other hand, are variant forms of a morpheme. For example, the morpheme used to express indefiniteness in English has two allomorphs — an before a word that begins with a vowel sound and a before a word that begins with a consonant sound. An would be used in front of a word like orange, but the allomorph a would be used in front of a word like car. Other examples of allomorphs include the pronunciation of the plural –s at the end of the words cats, dogs, and judges, where it is pronounced /s/ in the first case, /z/ in the second case, and /əz/ in the third. Morpheme and allomorph are similar in that they are both the smallest unit of language that carries information about meaning or function. However, they are different in the sense that an allomorph is a variant of a morpheme. In other words, one morpheme can result in two allomorphs but not vice versa. Also, a morpheme can be either free or bound, whereas an allomorph can only be bound. The morpheme student, for example, is free because it can be used as a word on its own; plural –s, on the other hand, is bound. The phonological variants of the plural –s in the above mentioned examples, which are allomorphs, are also bound since they cannot be used as words on their own. 2.2. Affixation and Subcategories Thereof. Affixation is the process of adding an affix to a word to produce an inflected or derived form. Unlike roots, affixes do not belong to a lexical category and are always bound morphemes. For example, the affix –er is a bound morpheme that combines with a verb such as teach, to create teacher, giving a noun with the meaning ‘one who teaches’. Affixes can be divided into three categories: prefixes, suffixes, and infixes. Prefixation is the process of attaching an affix to the front of its base. An example of prefixation is the attachment of the prefix re- to the base play, giving the word replay. Suffixation, on the other hand, is the process of attaching an affix to the end of its base. For example, the word faithful is the result of attaching the suffix ful to the end of the base faith. Both types of affixation occur in English. Far less common in English is the third category of affixation which is infixation: affixation that occurs within another morpheme. Plenty of examples of this type can be found in Arabic language where a base, typically made of three consonants, is inflected by adding vowel infixes, including some between the consonants, to express various grammatical contrasts. For example, the Arabic root drs is used to express various meanings, including tense, gender, and number, by the process of infixation where vowels are added to make words ‘darasa’ he studied, ‘adrus’ I study, ‘darasu’ they studied, etc. Derivational affixes are used to create new words from pre-existing forms. They can be divided into two categories. Class 1 derivations cause a change from the original to the new form. For example, the addition of the suffix –al, which converts the noun nation into the adjective national, causes the pronunciation of the first syllable to change from [nej] to [næ]. Another class 1 change is a shift in the stressed syllable of a word, as in the change from the noun pro'duct to the adjective produc'tive. Unlike class 1 derivations, class 2 derivations do not cause a change in the new form. ‘Gold’ still sounds like [gowld] when –ish is added to make ‘goldish’, for example. Finally, some words can have both class 1 and class 2 derivational changes, as in the word ‘derivational.’ The root ‘derive’ undergoes a class 1 change when it becomes ‘derivation,’ which then undergoes a class 2 change to become ‘derivational.’ 2.3. Root vs. Base: Similarities and Dissimilarities. The root is the core of a word and carries the major component of that word’s meaning. Roots typically belong to a lexical category, such as noun, adjective, verb, adverb, or preposition. Unlike simple words which are made of only roots, complex words typically consist of a root morpheme and one or more affixes. An example of a root is the verb teach in the word teacher. A base, on the other hand, is the form to which an affix is added. Both roots and bases are similar in that (a) they both take affixes, and (b) the base, in many cases, is also the root. In the example teacher, teach is both a root and a base having the affix –er suffixed to it. However, the root and base are different in that the base can be larger than a root, which is always just a single morpheme. This happens in words such as whitened, in which the past tense affix –ed is added to the verbal base whiten — a unit consisting of the root morpheme white and the suffix –en. In this example, white is not only the root for the entire word but also the base for –en. The unit white, on the other hand, is simply the base for –ed. Since roots are morphemes, they can be free or bound. The above examples of teacher and whitened contain free morphemes as their base, but in some English words, the affix(es) cannot be removed. The word unkempt, for example, was originally created by adding the prefix –un to the word kempt, which meant ‘tidy.’ Over time, kempt has fallen out of usage since there are several other words with similar meaning, so unkempt can no longer be split into un + kempt. The original root ‘kempt’ is now a bound morpheme, just like its prefix ‘un.’ Other examples include receive and inept because their roots are no longer used as words in English. 2.4 Ablaut vs. Reduplication Ablaut is the term used to refer to the inflectional internal change that substitutes one nonmorphemic segment for another to mark a grammatical contrast. For example, the verb drink forms its past tense by changing the vowel ‘i’ to ‘a’ to become drank. A similar change occurs in the inflectional change in ‘come’ when it is changed to the past tense, ‘came.’ An ablaut is also present in the change from some singular to plural forms, as in man → men and woman → women. Reduplication, on the other hand, is the morphological process which marks a grammatical or semantic contrast by repeating all or part of the base to which it applies. Full reduplication repeats the entire form. For example, the Turkish word for ‘prettily’ is gyzel, which is reduplicated as gyzel gyzel when the speaker/author means ‘very prettily.’ Partial reduplication copies only part of the base, as in the English phrase ‘itty bitty.’ Some languages make great use of full and/or partial reduplication, but it is rare in English, which tends to use other morphological changes to create new words. 2.5. Suppletion vs. Cliticization Suppletion is the morphological process that replaces one morpheme with an entirely different morpheme in order to indicate a grammatical contrast. Examples of this phenomenon in English include the use of went as the past tense form of the verb go and was and were as the past tense forms of be. Some linguists use the term partial suppletion to refer to what is considered to be an extreme form of internal change, where it is difficult to distinguish between suppletion and internal change. For example, is the past tense of think (thought) or teach (taught) an instance of suppletion or internal change? Cliticization refers to the morphological process that attaches certain elements that cannot stand alone to their preceding word (known as a host). These elements that cannot stand alone are in fact morphemes that behave like words in terms of their meaning and function, but are unable to stand alone as independent forms for phonological reasons. Clitics in English are the reduced variants of certain verb forms such as ’m for am and ’s for is. These variants cannot stand alone because they no longer constitute a syllable. Clitics can be subcategorized into two categories: enclitics and proclitics. Enclitics attach to the end of their host as in the English examples I’m and he’s. Proclitics attach to the beginning of their host. These are rare in English, but the Southern use of y’all to mean ‘you all’ (2nd person plural) is an example of a proclitic. The effects of cliticization can bear a superficial resemblance to affixation because in both cases, an element that can’t stand alone is attached to a base. The key difference is that unlike affixes, clitics are members of a lexical category such as verb, noun (or pronoun), or preposition. 2.6. Conversion vs. Deliberate Coinage Conversion is a process that assigns an already existing word to a new syntactic category. Even though it does not add an affix, conversion is often considered to be a type of derivation because of the change in category and meaning that it brings about. For this reason, it is sometimes called zero derivation. The three most common types of conversion in English are (1) a verb derived from a noun as in ship (the package), (2) a noun derived from a verb as in (a long) run, and (3) a verb derived from an adjective as in empty (the box). Less common types of conversion can yield a noun from an adjective as in the poor, and even a verb from a preposition as in up the price. Conversion is usually restricted to words containing a single morpheme, although there are some exceptions such as referee (noun to verb) and dirty (adjective to verb). Conversion in two-syllable words is often accompanied by stress shift in English. Usually the verb has the stress on the final syllable as in the verb recórd, whereas the noun has the stress on the first syllable as in the récord. Deliberate coinage is the process of creating words from scratch. Also known as word manufacture, deliberate coinage is especially common in the case of product names, such as Kodak, Dacron, and Teflon. New words can also sometimes be created from names, particularly from scientists or inventors. For example, watt is derived from James Watt, and Fahrenheit from Gabriel Fahrenheit. In some cases, brand names can become so widely known that they are accepted as generic terms for the product with which they are associated. The words Kleenex for ‘facial tissue’ and Xerox for ‘photocopy’ are two obvious examples of this phenomenon. A more recent example is the use of ‘Google’ or ‘google’ to mean ‘search for information, usually on the Internet.’ 2.7. Blending vs. Back-formation Blending is the process of creating words from non-morphemic parts of two already existing items, usually the first part of one and the second part of the other. The created words are called blends. Commonly used examples include brunch from breakfast and lunch, smog from smoke and fog, and motel from motor and hotel. Blending is also used to create names for crossbred animals as in liger from lion and tiger. Sometimes word formation is on the borderline between compounding and blending since larger parts of words are combined: electronic mail → e-mail, permanent press → perma-press. Back-formation is a process that creates a new world by removing a real or supposed affix from another word in the language. An example of this phenomenon is the creation of the verb resurrect, which was originally formed from the noun resurrection. Sometimes, backformation involves an incorrect assumption about a word’s form. For example, the word pea was derived from the singular noun pease, whose final /z/ was incorrectly interpreted as the plural suffix. Words that end in –or or –er have proven very susceptible to backformation in English. Because hundreds of existing nouns are the result of verb + –er affixation (runner, walker, singer, etc.) any word with this shape is likely to be perceived as a verb + –er combination. The words editor, peddler, and swindler were analyzed in this way, resulting in the creation of the verbs edit, peddle, and swindle. 2.8. Merge Operation vs. Move Operation: Definitions, Functions, Ordering Within Structures Merge and Move operations are two mechanisms used to analyze sentences and are part of the computational system of syntax. The process of forming a syntactic structure by Merge and/or Move is derivation, which always involves two distinct levels of syntactic structure: a deep structure (Dstructure) formed by Merge and a surface structure (S-structure) formed by Move and/or other operations. The Merge operation is a phrasal-level operation whereby two elements combine and form a phrase. This phrase has further combinations leading up to ever larger syntactic units. For example, the determiner ‘the’ can be combined with a noun to create a noun phrase, as in ‘the car.’ The noun phrase ‘the car’ can then be combined with a preposition to create the prepositional phrase ‘in the car.’ Since the Merge operation happens at the phrasal-level, it occurs before any Move operations. The Move operation is a sentence-level, structure-building operation causing a syntactic unit to move from its initial position in a sentence to a new one. Inversion is a type of Move operation that changes the position of the elements in the sentence; it does not affect sentence meaning. The Move operation is one of the tests used to determine phrase structure. If the sequence of words can be moved to a different part of the sentence and still retain its meaning, then it’s a phrase. The sentence, ‘On Tuesdays, they go to the mall,’ can easily be rearranged as, ‘They go to the mall on Tuesdays.’ Since the words ‘on Tuesdays’ can be moved, they are part of a phrase. There is a slight differentiation of meaning, though, in that the first example tends to emphasize the action of the verb (what they are doing), and the second example tends to emphasize the time the action of the verb occurs (when they are doing the action). 2.9. Clauses: Main vs. Subordinate Clauses are grammatical constructions that contain both a subject and a finite verb – a verb form (present or past tense) that can enter into a subject-verb agreement with the subject. A main or independent clause can stand alone as an independent sentence. For example, ‘We studied for hours to prepare for this exam,’ is a clause in itself, but it also contains a shorter clause, ‘We studied,’ which can be a complete sentence on its own. A subordinate or dependent clause must always be attached to a main clause and can be function as either an adjective, noun, or adverb. In the sentence, ‘The car that is parked in the garage belongs to him,’ the clause ‘that is parked in the garage’ functions as an adjective because it further explains which car (a noun). The clause ‘what you did’ functions as a noun in the sentence, ‘I know what you did.’ The third function is as adverb, as in the underlined clause in the sentence, ‘I know what you did when you were there last summer.’ 2.10. Complement vs. Complementizer A complement is a phrase or clause that relates back to the subject or another part of a sentence. Complements help complete the meaning of the phrase head. All languages tend to allow sentence-like complementation expressed as clauses. In English, some verbs allow multiple types of complement while others only accept one type. Some examples of the type of complement accepted by verbs include: Ø Mary is sleeping. (intransitive) NP Mary is buying presents. AP Mary looks upset. PPto Mary is talking to the neighbors. NP NP Mary enjoys buying her children Christmas presents. NP PPto Mary sometimes gives money to charities. NP PPfor Mary is buying presents for her children. NP PPloc Mary is setting the baby in the playpen. PPto PPabout Mary is talking to the clerk about the purchase she is making. A variety of complement options is also common with English nouns, adjectives, and prepositions. For example, the noun ‘present’ can occur without a complement or with prepositional phrases: ‘present for the boy,’ ‘present for the boy about to graduate.’ Likewise, adjectives can appear without complements or with prepositional phrases: ‘excited to go shopping,’ ‘worried about spiders.’ Clausal complementation has two parts: (1) the matrix or main/independent clause and (2) the complement or subordinate clause. These are joined together by a complementizer, which usually serves as the bridge between the matrix and the complement clauses. For example: Matrix Complementizer Complement Santa Claus didn’t know if Tonya had been good this year. whether that why 2.11. Questions: Yes/No vs. WhYes/no questions in English use the Move operation to shift the auxiliary verb from its original position (right of the subject and before the main verb) to the sentence-initial position. For example, the statement, ‘The workers should go on strike,’ becomes the yes/no question, ‘Should the workers go on strike?’ However, not all auxiliary verbs are operators – the verb form that moves to sentence-initial position in questions. At times, inversion is the only transformation needed when forming yes/no questions, but not all sentences have an operator, so adding an auxiliary (usually ‘do’) is required. There are three steps to converting a statement to a yes/no question in English. First, use the Merge operation to create an operator-lacking deep structure (D-structure) such as, ‘Girls like shopping.’ Second, use the insertion operation to fix an operator-lacking structure by adding ‘do,’ as in, ‘Girls do like shopping.’ Third, use the Move operation to relocate the operator ‘do’ to sentence-initial position: ‘Do girls like shopping?’ This is a question that can easily be answered with yes or no. Special questions are called wh- questions in English because of the words they use to ask questions that require more than a yes/no response: who, what, where, when, why, which, whom, whose, and how. In wh- questions, the wh- element is assumed to have already undergone a Move operation (wh- element relocation). The question, ‘What is Santa Claus bringing this year?’ is the surface structure (S-structure) that has the following statement as its D-structure: ‘Santa Claus is bringing what this year.’ The relocation of the wh- element is accounted for by another Move operation, namely operator relocation. The example sentence above will first shift ‘is’ to become the yes/no question, ‘Is Santa Claus bringing what this year?’ Next, the wh- element will be relocated to the sentence-initial position to create the wh- question, ‘What is Santa Claus bringing this year?’ Therefore, wh- questions can be said to undergo a two-step process to change from statements to questions: (1) Merge operation and (2) inversion and wh- movement. 2.12. Voice: Active vs. Passive Voice is the grammatical concept that shows whether the subject of a sentence is doing the action or having the action done to it. A sentence is called active if the subject of the sentence denotes the ‘agent’ or ‘instigator’ of the action denoted by the verb. The sentence ‘A thief stole the painting.’ is an active sentence since the subject ‘thief’ denotes the agent of the action denoted by the verb ‘stole’. In the passive voice, the subject is the recipient of the action. There are three properties of the passive voice. First, the importance of the agent (the logical subject and doer of the action) is greatly reduced or even completely omitted. Even when present, the agent assumes the syntactic function of a complement of a preposition, and the PP it occurs in is placed near or in sentence-final position. Compare, for example, ‘The dog has bitten the boy,’ which is in the active voice, and ‘The boy was bitten by the dog,’ which is in the passive voice. In the first example, it is clear that the dog is important and is the agent of the verb. The second example makes ‘dog’ the Oprep and shifts the importance of the sentence to ‘the boy.’ The second feature of the passive voice is that the function of the grammatical subject of a passive structure is typically carried out by a NP fulfilling the role of Od. For example, the active voice sentence, ‘The Grinch had stolen the presents,’ has ‘the presents’ as direct object. When changed to passive voice, the Od is now the subject: ‘The presents had been stolen by the Grinch.’ It’s also possible that an Oi could be used as the subject of a passive structure. The active voice sentence, ‘The Grinch gave the Whos their presents,’ for example, can be converted to the passive example, ‘The Whos were given their presents by the Grinch,’ with the indirect object ‘the Whos’ now functioning as subject. Finally, the passive voice has one major constraint on the type of verbs that can be changed from active to passive. Verbs that do not accept NPs as Od or Oprep cannot be converted to the passive voice. Sentences without a NPs as Od or Oprep do not have a structure that functions nominally, so the sentence doesn’t have a component that could become the subject. Even some sentences that do have NPs as Oprep cannot be changed from active to passive. For example, the active sentence, ‘Santa arrived on Christmas Eve,’ cannot be made into a passive construction: *‘On Christmas Eve was arrived by Santa.’