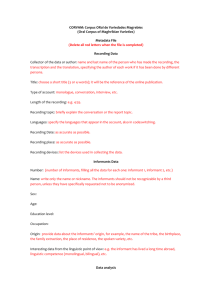

Ethnography

advertisement