The Income Elasticity of Demand for Construction Services (CNSTN)

advertisement

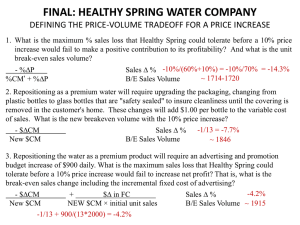

Price and Income Elasticity of Demand for Services in India: A Macro Analysis Satyanarayan Kishan Kothe Assistant Professor (Sr) Department of Economics University of Mumbai, Mumbai (INDIA) kothesk@gmail.com +91 9699200509 Abstract India has experienced phenomenal growth in recent period which is attributed by services revolution. India emerged as prominent service provider to the global consumers. Besides exports of services, Indian services are also consumed by domestic consumers. Domestic demand for services equally contributes in India’s services led growth paradigm. A systematic analysis of domestic demand for services is needed to understand services revolution in India. The paper estimates domestic demand for services. The attempt is made to estimate price and income elasticity of demand for services for 1951 to 2010. The Study endeavours to find structural changes in demand for services during pre and post liberalized period (1951 to 1990 and 1991 to 2010) through the most important determinants of demand for any product/service i.e. price and income. Keywords: Demand for Services, Price Elasticity of Demand, Income Elasticity of Demand, Consumption Expenditure and Elasticity of Demand for Services. Introduction: India’s services revolution and services led growth have raised various issues for discussion. The studies that have comprehend the sources of recent services revolution include Kothe and Kouthe (2009) entails role of exports of services in economic growth, the impact of FDI on services growth in India is discussed by Kothe and Sawant (2010), Kothe (2012a) endeavored to bring out the linkage of globalization and services revolution in India and Kothe (2012b) connoted that rise in demand for services with rise in per capita income induced more employment in services sector. Kothe (2013) also pronounced that increase in demand for services promoted capital formation in services sector in India. The standard export demand function for India’s services is estimated and theorized in Kothe (2014) that India’s services exports are highly income elastic and less immune to the changes in domestic prices. The discussion encourages the desire to find more insights of services revolution in the context of demand for services. Demand for services function can be as conventional as the demand for goods. Perhaps we find enough discussion about demand for goods functions, but not on demand for services. Engle’s Law (1857) is however more conventionalized by Clark (1951) that the employment in services sector increase with increase in income which implies that demand for services respond to the changes in income. Baumol (1967) explicitly modeled that the demand for services increases with the increase in income. Summers (1985) estimated price and income elasticities of demand for services classified under SNA for thirty four countries. And he also discussed service specific elasticities and their nature of response to price and income. Falvey and Gemmell (1991) stated that service income elasticities in aggregate tend to be statistically greater than, but numerically close to, unity. Further Falvey and Gemmell (1996) have been inclined to reject the hypothesis that income-elastic demand for overall services but found income elasticity estimates above and below unity for different types of services. Mahadevan and Kalirajan (2002) did find the income inelastic demand for services in Singapore. Hansda (2001) also remarked about the empirically found income elasticity of demand for services and also talked about the demand for services in India. Since there have not been attempts to find structural changes in the demand for services in India, the present study tries to discover the same if exist and compare the measures for pre and post liberalization period. Methodology and Data: As noted in Falvey and Gemmell (1996), Summers (1985) used following three equations for the estimation of income and price elasticity of demand for services. ln(𝐸𝑠 ⁄𝑌) = 𝛼1 + 𝛽1 ln 𝑅𝑌 + 𝑢𝑖 (1) ln(𝑅𝐸𝑠 ⁄𝑅𝑌) = 𝛼2 + 𝛽2 ln 𝑅𝑌 + 𝑢𝑖 (2) ln 𝑅𝐸𝑠 = 𝛼3 + 𝛽3 ln 𝑅𝑌 + 𝛾3 ln(𝑃𝑠 ⁄𝑃𝑔𝑑𝑝 ) + 𝑢𝑖 (3) Where 𝐸𝑠 is expenditure per capita on services and 𝑌 is GDP per capita, both converted to $ at nominal exchange rates; 𝑅𝐸𝑠 and 𝑅𝑌 are respectively “real” expenditure per capita on services and “real” GDP per capita (i.e. converted to $ using category specific PPP exchange rates). 𝑃𝑠 and 𝑃𝑔𝑑𝑝 are the (domestic) price of services and GDP respectively, and 𝑢𝑖 is a random error term. The nominal and real share of services rise with GDP per capita if 𝛽1 > 0 and 𝛽2 > 0 respectively, and services may be deemed to be income-elastic in demand if 𝛽3 > 0. Real expenditure (𝑅𝐸) here are equivalent to quantities - in national accounting terms - and thus equation (3) may be viewed as a simple demand function. It may attract objections that it omits ‘taste’ variable. Therefore a more complete specification is: ln 𝑅𝐸𝑠 = 𝛼4 + 𝛽4 ln 𝑅𝑌 + 𝛾4 ln 𝑃𝑠 + 𝛿4 ln 𝑃𝑐 + 𝜀4 𝑍 + 𝑢𝑖 (4) Where, Z is a vector of ‘test’ variables. It is to be noted that in (4) service and commodity prices (𝑃𝑠 and 𝑃𝑐 ) appear separately allowing testing of homogeneity condition 𝛿4 = −𝛾4 . Equations (3) and (4) can be used to estimate the income elasticities of aggregate or individual services with 𝑃𝑐 a ‘composite’ of commodity and other service prices in the later case. Therefore it is very much agreeable that equation (4) after omitting Z could be of help in estimation of price and income elasticity in our case. Z is a vector of ‘test’ variables that can be omitted to compare the results with that of Summers (1985). Though the above methodology does not accomplish the necessary data requirements are accepted by economists as general form of simple demand for services function. Hence for the computation of conventional demand function of goods/services one need to have the data on quantities of services, prices of services and GDP. There are few issues in defining quantities of services and prices of services. These issues have been sorted in the following discussion. As the quantities/units of services cannot be defined as structured as it is required and also are not readily available. Summers (1985) suggested that consumption expenditure are equivalent to quantities in national accounting terms, perhaps, as discussed above have estimated elasticity of demand for services with the help of consumption expenditure function for services. Prior to the estimation of demand for services, it is required to define the demand for services. But discussion by Hill (1999) makes it easier task to define the demand for services. The whole debate on conceptualization of services is carried out by Hill (1999) in which he discussed the issues in conceptualization of services and also about the tangibility and intangibility features of goods and services. In the deliberation he stated that services cannot exist independent of their producer, they consist of change brought about in the condition of one economic unit by the activities of another economic unit. Many services are capable of bringing material changes in persons or products. Since services are not entities, they cannot be stored at large. Therefore every unit of service is produced and consumed within a stipulated time. Many times the production and consumption of services is simultaneous. A very few services can be stored in physical nature. Having known this we can conclude the discussion about the storability characteristic of services and assume that every unit of service produced in the economy is consumed by either an individual as consumer service or an institution as producer service. In that sense, therefore, services GDP is same as the consumption expenditure on services. However the consumer expenditure on services does not interpret the demand for services truly. Though the consumer expenditure on services do not represent demand for services truly, the studies by Summers (1985), Falvey and Gemmell (1991) (1996) and Mahadevan and Kalirajan (2002) have considered the former as demand for services for the estimation of elasticities of demand for services. And also in the present study, elasticities are measured for demand for services function. Hence defining consumption expenditure on services in India is not that difficult though no official data is published on consumption of services. Having some arithmetic, we can get the data on consumption expenditure on services. The consumption expenditure on services would be equal to the services GDP (+/-) net services trade. In India, services price index is not measured, therefore it would not be appropriate to measure price elasticity using WPI or CPI both of which do not represent the changes in prices of services of which weights are too small and also do not cover all the services. The GDP deflator could be better measure in which prices of all the goods and services are approximated with their respective shares in GDP. Perhaps in the present study we have computed services output deflator i.e. the product of the ratio of nominal services output to real services output and hundred and considered that to be Services Price Index (Ps). Therefore the income and price elasticity of demand for services is measured by employing log linear regression of demand for services (CONSERi) on GDP (Yi) as income and Services Price Index (Ps) as price proxy for services. We have not only measured the price and income elasticity but also attempted to find structural changes, if any, in the aggregate demand for services function in pre and post liberalization period i.e. 1951 to 1990 and 1991 to 2010. Therefore unlike equation (3) equation (5) estimates price and income elasticity of demand for services for the entire sample period. In the present study relatively simple demand for services function, unlike Summers (1985), Falvey and Gemmell (1996) is estimated with the help of following equation. ln 𝐶𝑂𝑁𝑆𝐸𝑅𝑡 = 𝛼1 + 𝛽1 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝛽2 ln ( 𝑃𝑆𝑡 𝑃𝑅𝑆𝑡 ) + 𝑢𝑡 (5) Where 𝐶𝑂𝑁𝑆𝐸𝑅 is the demand for services, 𝑌 represents the GDP at constant prices, 𝑃𝑠 is the Services Price Index and 𝑃𝑅𝑆 is the Price Index of Rest of the Services GDP, further and t represent time. And t =1951 to 2010. Perhaps, to discover the structural changes in demand for services, existing methods suggest the use of Chow test (1960) on priory basis. Two different regressions could have been run and applying Chow test (1960), useful to examine the structural stability of a regression model, which would help in deciding whether the two periods give two different demand functions or there is no need to do so. And also is possible to find structural change if any in two different periods. But Chow test has its own limitations, as it is powerless to provide reasons for the structural change if any. Such a structural change is due to difference in slopes or intercept or both from each of the regressions of a model. But instead of that we have used dummy variable approach by Gujarati (1970) that is more capable of providing specification of any such difference. However after reviewing the available methodologies the final call is taken on to use the following function form of the model. Therefore equation (6) attempts to find structural changes in demand for services during pre and post liberalized period through the most important determinants of demand for any product/service i.e. price and income. 𝑃𝑆𝑡 ln 𝐶𝑂𝑁𝑆𝐸𝑅𝑡 = 𝛼1 + 𝛼1 𝐷1𝑡 + 𝛽1 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝐷1𝑡 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝛽2 ln ( 𝑃𝑅𝑆𝑡 ) + 𝐷1𝑡 ln ( 𝑃𝑆𝑡 𝑃𝑅𝑆𝑡 ) + 𝑢𝑡 (6) And t =1951 to 2010. 𝐷1 = 1 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑡 = 1951 𝑡𝑜 1990 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝐷1 = 0 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑡 = 1991 𝑡𝑜 2010 Where 𝐶𝑂𝑁𝑆𝐸𝑅 is the demand for services, 𝑌 represents the GDP at constant, 𝑃𝑠 is the Services Price Index and 𝑃𝑅𝑆 is the Price Index of Rest of the Services GDP, further t 𝑃 represents time. 𝐷1 is dummy variable associated with 𝑌 and (𝑃 𝑆𝑡 ) which define 𝐷1 = 1 for 𝑅𝑆𝑡 pre and 𝐷1 = 0 for post liberalization period respectively. Similar way for the sub-sectors in services, demand functions are estimated and price and income elasticities are measured. India’s national accounting system facilitate the disaggregation of output of services into four categories, that are 1) Construction, (CNSTN) 2) Trade, Hotel, Transportation and Communication, (THTC) 3) Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Business Services (FIRB) and 4) Community, Social and Personal Services (CSPS). For this purpose equation (5) and (6) are formed as base equations and the following generalized form of equations are used to estimate the price and income elasticities of demand for group of services stated above. 𝑃 ln 𝐶𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼1 + 𝛽1 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝛽2 ln (𝑃 𝑖𝑡 ) + 𝑢𝑡 (7) 𝑅𝑖𝑡 where 𝐶𝑖 is consumption expenditure in i sub service, 𝑌 is the GDP, and 𝑃𝑖 is the Services Price Index of ith sub service and 𝑃𝑅𝑖 is the Price index of rest of the sub services GDP and lastly t represents time. And t = 1951 to 2010. And to evaluate the structural changes in demand for sub services as earlier the following equation is used. 𝑃 𝑃 ln 𝐶𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼1 + 𝛼1 𝐷1𝑡 + 𝛽1 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝐷1𝑡 ln 𝑌𝑡 + 𝛽2 ln (𝑃 𝑖𝑡 ) + 𝐷1𝑡 ln (𝑃 𝑖𝑡 ) + 𝑢𝑡 𝑅𝑖𝑡 𝑅𝑖𝑡 (8) And t =1951 to 2010. where 𝐶𝑖 is consumption expenditure in i sub service i.e. CNSTN, THTC, FIRB and CSPS, 𝑌 is the GDP, 𝑃𝑖 is the Services Price Index of i sub service i.e. 𝑃𝑐𝑛𝑠𝑡𝑛 , 𝑃𝑡ℎ𝑡𝑐 , 𝑃𝑓𝑖𝑟𝑏 and 𝑃𝑐𝑠𝑝𝑠 and 𝑃𝑅𝑖 is the Price index of output of rest of the i sub services, further t represents time. 𝐷1 is dummy variable associated with 𝑌 and 𝑃𝑖𝑡 𝑃𝑅𝑖𝑡 which define 𝐷1 = 1 for pre and 𝐷1 = 0 for post liberalization period respectively. All the variables at level i.e. the demand for services (𝐶𝑂𝑁𝑆𝐸𝑅) demand for CNSTN, demand for THTC, demand for FIRB and demand for CSPS, GDP (𝑌), ratio of the Price 𝑃 𝑃 Indices (𝑃 𝑆 ) and (𝑃 𝑖 ), dummy variable (D1) and its product with GDP (D1𝑌) and ratio of 𝑅𝑆 𝑅𝑖 𝑃 𝑃 Services Price Indices 𝐷1 ln (𝑃 𝑆 ) and all 𝐷1 ln (𝑃 𝑖 )s are tested for stationarity, as the 𝑅𝑆 𝑅𝑖 variables form time series, with the help of augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) (1979) and Phillips-Perron (1988) test for unit root. And both the tests confirmed that all the variables found to be non-stationary at level. According to Granger (1986), if variables are individually non-stationary and are I(1), that is, they have stochastic trends, their linear combination is I(0). The linear combination cancels out the stochastic trends in the two series. As a result, a regression of such non-stationary variables at level would be meaningful (i.e., not spurious). It is said that the two variables are cointegrated. Economically speaking, two variables will be cointegrated if they have a longterm, or equilibrium, relationship between them. Here the meaning of equilibrium is not as same as it is used in economic theories. Hence, equation (5) and (6) are tested with the help of Engle-Granger test (1987) for a cointegrating regression and also observed that these regressions are not spurious, even though individually the two variables are non-stationary. Therefore we run log linear regression to find the demand for services function which ultimately estimates the income and price elasticity of demand for services. Such a regression may be called the static or long run demand for services function and interprets its parameters as long run parameters. Therefore the parameters represent long run income and price elasticity of demand for services. The present study also attempts to find the change in elasticity are due to structural change, if any, between pre and post liberalized period by including dummy variable to distinguish the period. Results and Observations We estimated the above equations (5) and (6) to measure the response in demand for services due to changes in price and income. We obtain three estimates from above equation (5) and (6) that are summarized in the table (1). Table 1: Income and Price elasticity of Demand for Services Income Elasticity of Demand Price Elasticity of Demand 𝜷𝟏 = 𝜺𝑬𝑿𝑷/𝒀 𝜷𝟐 = 𝜺𝑬𝑿𝑷/𝑷𝒔 1951 to 2010 1.169 -0.29 1951 to 1990 1.218 -0.219 1991 to 2010 1.125 0.683 Summers (1985)** 0.977 -0.06 Falvey and Gemmell (1996)** 0.979 -0.32 Period * All the measures are significant at 5 per cent level of significance Source: Author’s estimation and ** are from Summers (1985) and Falvey and Gemmell (1996) Income Elasticity of Demand for Services (Total) The income elasticity of demand for services (Total) is obtained from regression equations (5) and (6). Results reported in Table (1) were obtained using ordinary least squares (OLS) method. Our long run estimate of income elasticity of demand for the period of 1951 to 2010 found to be 1.169 which suggests that demand for services is elastic in response to change in income. Therefore the empirical hypothesis that services are always supposed to be income-elastic in demand is accepted. The results also suggest that services were more income elastic in pre liberalized period in comparison to post liberalization. Decline in income elasticity of demand for services in the post liberalized period suggests that service that were once luxurious now tend to become comparatively less luxurious. Therefore that is the change occurred in the behavior of the consumers in post liberalized period that services once were luxuries have tend to become relatively normal good but it remained luxurious by and large. Perhaps, it would be more appealing if we disaggregate the services and see how the behavior of income elasticity of demand is found to be for the group of services for the entire sample period and in also pre and post liberalization period. The reason for that is services are heterogeneous and the need for services also differs from group to group. Though not comparable with that of Summers (1985) and Falvey and Gemmell (1996) our estimated results in long run are greater than that of from these two studies imply that services in India are luxurious in total and found to income elastic in nature. The national database does not classify each service separately rather it groups the services. Therefore eventually our analysis limits ourselves to the group of services rather than each service. But still with the given limitations our estimates provide enough substance to elaborate broader perspective about income elasticity of demand for group of services. We estimated the equations (7) and (8) to measure the response in demand for services, for each group separately, due to changes in price and income. We obtain one estimate from above equation (7) and two from equation (8) that are summarized in the table (2). The Income Elasticity of Demand for Construction Services (CNSTN) The general definition of demand for construction services include demand for housing, demand for commercial and industrial buildings, demand for infrastructure such as roads, hospitals, schools, bridges, ports, airports, dams, etc., demand for repair and maintenance. With increase in income the need for all such demand for construction services also rise. That indicates that income elasticity of demand for construction always is greater than 1. Table 2: Group wise Price and Income Elasticity of Demand for Services Price and Income Elasticity of Demand for group of Sub Services Period Construction (CNSTN) Trade, Hotel, Transportation and Communication (THTC) Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Business Services (FIRB) Community, Social and Personal Services (CSPS) Income Price Income Price Income Price Income Price 1951 to 2010 1.378 -1.108 1.325 -0.279 1.042 -0.604 1.093 -0.735 1951 to 1990 1.478 -1.207 1.398 -0.388 0.962 -0.499 1.174 -0.497 1991 to 2010 0.956 0.660 1.402 0.141 0.958 -0.136 0.922 1.193 * All the measures are significant at 5 per cent level of significance Source: Author’s estimation The long run income elasticity of demand for construction services has been found to be 1.378 which is significantly greater than 1. It seems that construction services in India have been more income elastic and classify themselves as luxury services. Its importance in the economy is narrated in the Report of Working Group on Construction (2011) that construction industry is the second largest employer after agriculture, and an economic entity causing and generating large multiplier effect, value added employment potential, construction can add substantially to the growth and substance of the national economy. Construction sector has two key segments: (i) Residential and Non-Residential Buildings (Residential, commercial, institutional, industrial); and (ii) Infrastructure. Infrastructure contributes roughly 50 per cent to the construction sector and the remaining is through residential and non-residential building industry. We may find bi-directional causal relationship between infrastructure and growth. However, post liberalized two decades have recorded income elasticity of demand for construction around 0.96 though it is greater than zero and approaches to 1 but compare to pre liberalization period (1.48) it is declined by 50 per cent. The reason for that is surely the steep rise in the prices in the industry in the post reforms period that are related to the prices of inputs and also the rising demand for construction products in the later period. The change in the income elasticity can be inferred in the context of the change in the nature of the services to consumers. In the pre liberalized period construction services were highly luxurious now in the later period tend to become the normal luxury commodity. The Income Elasticity of Demand for Trade, Hotel, Transportation and Communication (THTC) The income elasticity of demand for THTC services in the long run is observed to be 1.325 which implies that Trade, Hotel, Transportation and Communication services have been income elastic and formed themselves as luxurious services. The study does not find significant difference between the income elasticity of demand for services in pre and post liberalized periods. They have maintained their luxury status intact since last sixty years. Further disaggregation may lead to have significant differences in the elasticity estimate during the same periods. It can be proved with the help of taking the growth indicators and elasticity estimates form a dominantly growing sector among THTC. DOT, India while highlighting the telecom sector necessitates a world class telecommunication infrastructure is the key to rapid economic growth and to bring social change. Indian telecommunication sector has undergone a major process of transformation through significant policy reforms, particularly beginning with the announcement of NTP 1994 and was subsequently re-emphasized and carried forward under NTP 1999. Driven by various policy initiatives, the sector witnessed a complete transformation in the last decade. It has achieved a phenomenal growth during the last few years and is poised to take a big leap in the future also. The growth of the sector in the recent past averaged annually around 45 per cent. Such a rapid growth in the communication sector has become necessary for further modernization of Indian economy through rapid development in IT. Hence growth indicators and income elasticity in THTC contradict in some way. Unless you have approximately 32 per cent growth in the economy, you cannot have income elasticity of 1.4 per cent. Therefore, undoubtedly disaggregation of the THTC would lead to significant differences in the estimates. The similar stories could be observed in trade, hotel and transport sectors. The Income Elasticity of Demand for Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Business Services (FIRB) The income elasticity of demand for FIRB services in the long run is 1.04 which implies that Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Business Services have been income elastic and appeared to be luxurious services. The study does not find significant difference between the income elasticity of demand for services in pre and post liberalized periods, but has been less than one in both periods. They have been considered to be luxurious since last sixty years. The stability of the estimate in the long run is associated with the decline in the relative prices in these sectors. The business services sector includes the ICT sector that has been key sector in the recent services revolution occurred in the economy. But a separate estimate of income elasticity of demand for services could provide the cushion for the arguments to discuss the amicable estimates of elasticity of demand for business services. The Income Elasticity of Demand for Community, Social and Personal Services (CSPS) The income elasticity of demand for CSPS services in the long run is registered around 1.1 which indicates that the community, social and personal services are income elastic. The luxury nature of the service is not found to be same in pre and post reform period. CSPS services were relatively more luxurious in pre reforms period compare to the later. There has been significant change in the elasticity of demand for CSPS in pre and post liberalized period that have been 1.17 and 0.92 respectively. These differences are associated with the role of the government as most of the services include have public good characteristic in pre reform period and the services become later either private-public or government reduced expenditure significantly that includes general administration and have privatized or private players are allowed to provide services mainly in health and education sectors. Hence it can be concluded that the long run estimate of income elasticity of demand for all the group of services for the period of 1951 to 2010 found to be greater than one which suggests that the demand for services are highly income elastic. Therefore the empirical hypothesis that services are always supposed to be income-elastic is accepted. The income elasticity estimates corresponding to CNSTN, FIRB and CSPS are found to be 0.96, 0.96 and 0.92 respectively for the period 1991-2010 which implies that during post reforms period CNSTN, FIRB and CSPS were elastic in response to income. But THTC have maintained its nature of income elasticity of demand even after reforms. Therefore, in real sense THTC have been luxurious services since last sixty years. Price Elasticity of Demand for Services (Total) The price elasticity of demand for services (Total) is obtained from regression equations (5) and (6). Results reported in Table (1) were obtained using ordinary least squares (OLS) method. We discovered long run estimate of price elasticity of demand for the period of 1951 to 2010 i.e. -0.219 which suggests that demand for services is inelastic in response to change in price. The price elasticity of demand for services is computed using equation (5), unlike summers (1985) in which he used the ratio of services price to prices of GDP, where we have made some rectification, as suggested by Falvey and Gemmell (1996) to use price of ‘composite’, and used the ratio of prices of services to prices of rest of the services output in the economy. Therefore our elasticity estimate of price is quite different than that of Summers (1985) and Falvey and Gemmell (1996). Therefore the empirical hypothesis that the estimate of price elasticity for goods/services for the period of 1961-2010 is expected to be negative (less than zero) is accepted. The results from equation (6) also suggest that services were price inelastic in pre liberalized period. Perhaps the same is not true in post reforms period. The structure of demand for services in response to price is changed in the post reform period. A one per cent increase in prices of services compare to prices of other goods/services in the economy increases the demand for services by 0.68 per cent. Perhaps, it would be more appealing if we disaggregate the services and see how the behavior of price elasticity of demand is found to be for the group of services for the entire sample period and also in pre and post liberalization period. We estimated the equations (7) and (8) to measure the response in demand for services, for each group separately, due to changes in price and income as stated above. Price Elasticity of Demand for Construction (CNSTN) The construction sector is highly price sensitive sector in the economy, though it is one of the basic needs. It is not only housing but all sorts of construction either for individual household or industry also fulfills the criteria of a basic need. As housing is necessity for households, buildings are essential for industries, hospitals are necessary part of each individual, and roads are required for all the stakeholders in the economy. Therefore output of construction industry holds the property of basic needs. The empirical studies suggest that price elasticity of demand for necessary goods/services as also for construction must be zero. Perhaps our estimate contradicts the expected price elasticity of demand for construction. The long run price elasticity of demand for construction services in the economy for the period 1961 to 2010 found to be -1.1. It implies that with 1 per cent increase in prices of construction there is decrease in demand for construction services by 1.1 per cent. Therefore the demand for construction services is more elastic. But in pre reforms period, demand for services found to be more elastic (-) whereas the post reforms period records positive elasticity of demand for construction services. Perhaps price elasticity of demand for construction services in post reforms period suggests that prices of construction services rise by 1 per cent, the demand for construction services rise by 0.66 per cent. It is evident from the prices of housing, and all sorts of construction that rose three fold due to rise in the input prices in last two decades, but the demand for consumption services have been persistently rising in post liberalized period. The rapid growth of the Indian economy has had a cascading effect on demand for commercial property to help meet the needs of business, such as modern offices, warehouses, hotels and retail shopping centers. Price Elasticity of Demand for Trade, Hotel, Transportation and Communication (THTC) The long run price elasticity of THTC services is registered to -0.28 for the period of 1951 to 2010. It shows that THTC have been price inelastic since 1951. But same is recorded around -0.39 for the period of 1951 to 1990, indicates that degree of elasticity is higher during the later period. Perhaps 1991 to 2010 is the period in which we get price elasticity around 0.14 that indicates that demand responded positively to the rise in price though less proportionately. We find here structural change in the shape of demand curve of THTC services. The degree of price elasticity proposes that THTC services have been comparatively necessary services. More or less comparable results are ascribed by Deb and Filippini (2013) that the price elasticity of demand for transport is around -0.35 and he also stated that the low elasticity values indicate that the public transport in India is a necessity. Though the results in the present study are not comparable truly with that of Deb and Filippini (2013) but depict the macro scenario of the THTC which also includes transportation. Therefore it provokes to state that the trade, hotel, transportation and communication have become necessary services in the post liberalized period and the rising prices do not affect the demand for these services. Moreover the price elasticity estimate suggests that increasing prices do not cause for decline in the demand but increase the demand for these services. Price Elasticity of Demand for Finance, Insurance, Real Estate and Business Services (FIRB) Cole, Sampson and Zia (2010) rightly stated that increased demand by households for financial services may improve risk-sharing, reduce economic volatility, improve intermediation, and speed overall financial development. This in turn could facilitate competition in the financial services sector and, ultimately, more efficient allocation of capital within society. The consumption of financial services facilitate benefits to individuals i.e. individuals may save more, and better manage risk, by purchasing insurance contracts. Therefore a competitive financial and insurance sector is always well demanded by the society and same is equally true for demand for real estate and business services. India’s FIRB sectors show less elastic demand in response to prices. In the long run, the elasticity of demand for FIRB services found to be -0.6 which indicates that during 1951 to 2010 the FIRB services were less elastic. The aggregate behavior of the consumer for FIRB services in pre liberalized period recorded -0.499 and that in post reforms period it is -0.136, the difference in the estimate in these two period indicate the change in the behavior of the individuals in relation to demand for FIRB services in response to the price variable. It also suffices to confirm that the FIRB services tend to be necessary services in the post reforms period. Price Elasticity of Demand for Community, Social and Personal Services (CSPS) Education and health constitute an important part of the community, social and personal services. The long run price elasticity of demand for CSPS shows that CSPS have been less elastic, recorded price elasticity of demand (-0.735). That indicates that during 1951 to 2010 the price elasticity of demand for CSPS services was less than one. But we found some unusual estimates in pre and post reforms period as far as the price elasticity of demand for CSPS are concerned. We found that the former period estimate is negative (-0.497) whereas the late period recorded positive (1.19) elasticity of demand for CSPS services. As it is accepted that demand for education and health is very high in developed countries as also in developing country like India. The increase in price may not affect the demand for these services, either government subsidizes or individuals spent from their valets. Papola and Sahu (2012) have rightly described that an increase in per capita income raises the demand for personal services at an unprecedented rate. Media and entertainment services and security services have shown enormous growth. Services towards household management and personal care are also emerging fast, particularly in urban areas. Many of these services at present are provided by semi-skilled and low-paid workers on an unorganized basis. Their increasing demand warrants that appropriate institutional and organizational mechanisms are developed to ensure services of reasonable standard to the consumers, on the one hand, and reasonable earnings to those rendering these services, on the other. Existence of such mechanisms is likely to increase demand for these services. The above explanation by Papola and Sahu (2012) subscribe to our estimates that even if the price changes by 1 per cent there would be increase in demand for CSPS by more than 1 per cent. Conclusion: Our long run estimate of income elasticity of demand for the period of 1951 to 2010 found to be 1.169 which suggests that demand for services is elastic in response to change in income. The results also suggest that services were more income elastic in pre liberalized period in comparison to post liberalization. Decline in income elasticity of demand for some services in the post liberalized period suggests that service that were once luxurious now tend to become comparatively less luxurious. Therefore that is the change occurred in the behavior of the consumers in post liberalized period that the services once were luxuries have tend to become relatively normal luxury services. Therefore the services revolution observed in India in recent period, that generated more per capita income, have impacted demand for services. We discovered long run estimate of price elasticity of demand for the period of 1951 to 2010 i.e. -0.219 which suggests that demand for services is inelastic in response to change in price. Estimates also suggest that services were price inelastic in pre liberalized period. Perhaps the same is not true in post reforms period. If the prices of services increase by 1 per cent that uncommonly increases the demand for services by 0.68 per cent. Therefore we found structural change in demand for services in response to price in the post reform period compare to the earlier. Hence the change in prices of services also have significant impact on demand for services in the post liberalized period which is characterized by services revolution in India. The rising demand for services is caused by the dissemination of information and knowledge through latest communication and IT technology. With the increase in income, any increase in demand for services like, health, education, telecommunication, transportation and IT and ITES would enhance productivity of households. Recognizing the role of communication and IT and ITES in boosting the productivity, the Govt. of India and private firms in India have initiated the IT education and training to enhance the skills of workforce in the country. That would further generate more income from services and help the economy to sustain the services led growth. References: Baumol, W. (1967). Macroeconomics of Unbalanced Growth: the Anatomy of Urban Crisis. American Economic Review, 57(4): 415-426. Chow, G. C. (1960). Tests of Equality between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions. Econometrica, 28(3): 591-605. Clark, C. (1957). The Conditions of Economic Progress. London: MacMillan. Cole, S., Sampson, T. & Zia, B. (2011). Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets? The Journal of Finance, (66): 1933–1967. Deb, K. & Filippini, M. (2013). Public Bus Transport Demand Elasticities in India. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 47(3): 419-436. Dickey, D. A. & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, (74): 427-431. Engle, R. F. & Granger, C. W. J. (1987). Co-integration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation and Testing. Econometrica, (55): 251-276. Falvey, R. E. & Gemmell, N. (1991). Explaining Service Price Differences in International Comparisons. American Economic Review, (81): 1295-1309. Falvey, R. E. & Gemmell, N. (1996). Are Services Income-Elastic? Some New Evidence. Review of Income and Wealth, (42): 257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4991.1996.tb00182.x Granger, C. W. J. (1986). Developments in the Study of Co-Integrated Economic Variables. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, (48): 226. Gujarati, D. (1970). Use of Dummy Variables in Testing for Equality between Sets of Coefficients in Two Linear Regressions: A Generalization. American Statistician, 24(5): 1821. Hansda, S. K. (2001). Sustainability of Services-led Growth: An Input-Output Analysis of Indian Economy, RBI Occasional Working Paper, 22(1, 2 and 3). Hill, P. (1999). Tangibles, Intangibles and Services: a New Taxonomy for the Classification of Output. Canadian Journal of Economics, 32(2): 426-447. Kothe, S. K. (2012a). Globalization and Services Revolution in India. Research Volume Jagtikikarananantarchi Bhartiya Arthvyavasthetil Sthityantare by The Annual Conference of Marathwada Arthshastra Parishad, February 2012, 197-202. ISBN 978-81-908303-2-4. Kothe, S. K. (2012b). Inter-Sectoral Shifts in Employment and Employment Elasticity in Service Sector in India. International Journal of Development Studies and Research, 1(1): 159-167. Kothe, S. K. (2014). Standard Export Demand Function for India’s Services. International Journal of Trade & Global Business Perspectives. 3(1): Kothe, S. K. & Kouthe, P. K. (2009). Services Exports and Economic Growth: Is there any Causality? A Case Study of India at National Seminar on ‘Development Issues in the Changing Scenario’ organized by Birla College, Kalyan on 28th and 29th March 2009. Kothe, S. K. & Sawant, A. (2010). Global Financial Crisis and FDI in Services Sector in India. In Baskaran, A. & Soundararaj, J. J. (Eds.), The Impact of Foreign Direct Investment on Indian Economy. Excel Books, May 2010. pp. 259-268. Mahadevan, R. & Kalirajan, K. P. (2002). How Income Elastic Is The Consumers Demand For Services In Singapore? International Economic Journal, 16(1): 95-104. Papola, T. S. & Sahu, P. P. (2012). Growth and Structure of Employment in India -LongTerm and Post-Reform Performance and the Emerging Challenge. Retrieved from http://isidev.nic.in/pdf/ICSSR_TSP_PPS.pdf Phillips, P. C. B. & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series Regression. Biometrika, (75): 335-346. Report of Working Group on Construction (2011). Planning Commission, India. Summers, R. (1985). Services in the International Economy. In R. P. Inman (Ed.), Managing the Service Economy. Problems and Prospects, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1985.