Business Case - Department for International Development

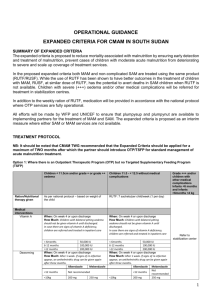

advertisement