Diet, weight loss and Cardiovascular disease (3)

advertisement

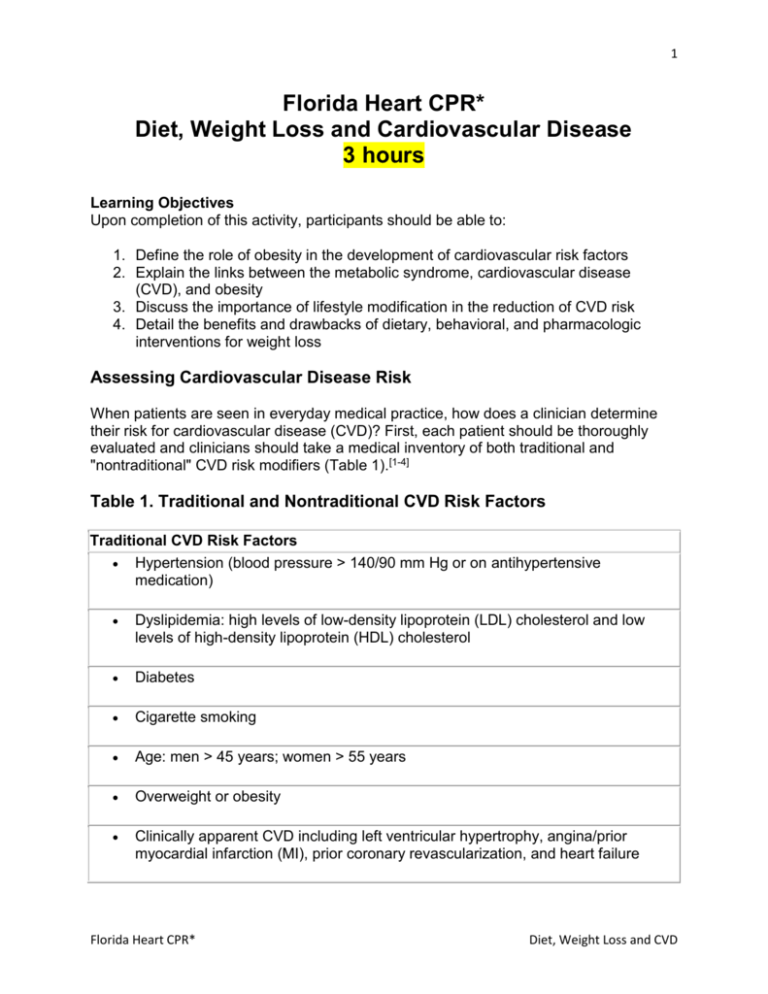

1 Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Disease 3 hours Learning Objectives Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to: 1. Define the role of obesity in the development of cardiovascular risk factors 2. Explain the links between the metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and obesity 3. Discuss the importance of lifestyle modification in the reduction of CVD risk 4. Detail the benefits and drawbacks of dietary, behavioral, and pharmacologic interventions for weight loss Assessing Cardiovascular Disease Risk When patients are seen in everyday medical practice, how does a clinician determine their risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD)? First, each patient should be thoroughly evaluated and clinicians should take a medical inventory of both traditional and "nontraditional" CVD risk modifiers (Table 1).[1-4] Table 1. Traditional and Nontraditional CVD Risk Factors Traditional CVD Risk Factors Hypertension (blood pressure > 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medication) Dyslipidemia: high levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol Diabetes Cigarette smoking Age: men > 45 years; women > 55 years Overweight or obesity Clinically apparent CVD including left ventricular hypertrophy, angina/prior myocardial infarction (MI), prior coronary revascularization, and heart failure Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 2 Family history of CVD Nontraditional CVD Risk Factors Elevated fasting insulin (impaired glucose tolerance) Elevated low apolipoprotein B Small dense LDL Microalbuminuria C-reactive protein Of course, no risk factor should be considered in isolation. The most recent publications from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) on managing high blood pressure and dyslipidemia emphasize the importance of considering multiple (> 2) risk factors in determining CVD risk.[1,2] Indeed, the recently released Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III [ATP III]) uses projections from the Framingham Heart Study of 10-year absolute coronary heart disease (CHD) risk (ie, the percent probability of having a CHD event in 10 years) to identify which patients with multiple risk factors require more intervention to prevent cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, for the first time, the ATP III has called specific attention to the importance of targeting the metabolic syndrome, a constellation of cardiovascular risk factors including abdominal obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, as a new method of risk-reduction therapy.[2] While each factor independently modifies the risk of CVD, they may not work just in additive fashion, but also synergistically to multiply a person's risk.[5] Thus, clinicians should determine a patient's CVD risk based on all potential risk modifiers. After all, CVD is a progression that begins and continues through a complex interaction between the environment and genetics. In time, more and more CVD risk factors are sure to emerge, thereby providing further targets for therapeutic intervention. Nevertheless, each and every risk factor should be viewed in relation to the others when deciding upon intervention. In summary, clinicians should view cardiovascular risk in a global way. From Hypertension to CVD Hypertension has a dramatic impact on CVD risk for people of all ages and both sexes.[5-7] A 36-year follow-up of individuals aged 35-64 years in the Framingham Heart Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 3 Study showed that hypertensive patients have an excess risk of CHD, stroke, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure compared with patients with normal blood pressure. Although numerous trials have shown that lowering blood pressure provides much benefit, CVD is not eliminated. One reason for this lack of elimination is that hypertension tends to cluster in patients with other cardiovascular risk factors, such as abnormalities of glucose, insulin, and lipoprotein metabolism.[8] Furthermore, hypertensive patients are more likely to be obese, to smoke cigarettes, and to have a family history of CVD compared with their normal counterparts.[5-7] Adding any one of these factors to a person's risk repertoire can double the CVD risk associated with hypertension.[3] In addition, taken separately, each factor is a population marker for CVD. Since these risk factors interact to promote heart disease, clinicians must consider each individual's collective risk when treating hypertension.[9] Interrupting the Cascade of CVD Before any clinically apparent disease, patients often show other evidence of diffuse vascular and organ damage, which ultimately progresses to morbid events. Ordinarily, the changes that occur early in the cardiovascular continuum are subtle and difficult to tease out. Discovering vascular endothelium dysfunction, changes in arterial compliance or elasticity, arterial wall thickness, and left ventricular hypertrophy all require imaging techniques. Microalbuminuria and vascular calcification are other important, usually clinically silent, CVD markers. Thus, the onus is on clinicians to probe for these markers of CVD. Identifying, modifying, and treating these risk factors may halt the development and progression of CVD. The Fattening of America and CVD Risk An estimated 61% of American adults are overweight, while 26% are obese, according to results of the 1999 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). [10] Statistics reveal an increase in prevalence of obesity and overweight for both sexes, all races/ethnicities, age groups, and educational levels in the United States since the NHANES III survey was completed in 1994, and all measures suggest continuing trends toward an ever-fatter America. From a global perspective, the increase in the prevalence of obesity is similarly alarming.[11] Indeed, both the NHLBI and the World Health Organization (WHO) have classified obesity as an epidemic. (The NHLBI defines overweight as a body mass index [BMI, in kg/m2] of 25.0-29.9 and obesity as a BMI of >/= 30.[12]) Overweight and obesity kill approximately 300,000 Americans annually, [13] taking an economic toll of $117 billion each year.[14] Overweight and obesity have been shown to sharply increase the risk of hypertension; stroke; endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon cancers; gallbladder disease; osteoarthritis; sleep apnea; respiratory problems; and CVD mortality. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 4 The burgeoning obesity epidemic has contributed to a concurrent explosion in the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.[15-18] An estimated 16 million Americans have diabetes, with type 2 diabetes accounting for up to 95% of these cases.[19] This number is expected to grow as the population at large is aging and becoming more obese and sedentary.[20,21] A host of studies have clearly established that overweight and obesity are among the most important risk factors for developing glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes.[15-23] Of interest, CVD accounts for 75% of diabetic mortality.[24] Metabolic Syndrome: A Less Recognized Obesity-Associated Epidemic Although a fasting glucose > 126 mg/dL is known to be associated with an elevated risk of CVD, there is a continuum of CVD risk from normal glucose tolerance all the way through to diabetes. It is somewhere in this range of CVD risk that the estimated 47 million Americans with the metabolic syndrome fall.[18] The metabolic syndrome, also known as impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) or the insulinresistant syndrome, has been defined in a variety of ways but is predominantly diagnosed by an insulin-resistant hyperinsulinemia in overweight individuals or in those with abdominal obesity. At its essence, the metabolic syndrome is a cluster of characteristics that together increase the risk of diabetes and CHD in addition to numerous other health problems. According to the ATP III,[2] individuals with 3 or more of the following characteristics have the metabolic syndrome: Abdominal obesity: waist circumference > 102 cm in men and > 88 cm in women Hypertriglyceridemia: >/= 150 mg/dL (1.69 mmol/L) Low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol: < 40 mg/dL (1.04 mmol/L) in men and < 50 mg/dL (1.29 mmol/L) in women High blood pressure: >/= 130/85 mm Hg High fasting glucose: 110 mg/dL (>/= 6.1 mmol/L) Using data from NHANES III, Ford and colleagues[18] at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated an age-adjusted prevalence of the metabolic syndrome of 23.7% in the United States. Thus, extrapolating out from 2000 census data, about 47 million US residents have the metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, since the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome increases with age, it is estimated to affect more than 40% of Americans over 60 years of age. Evaluating these data by ethnicity, Mexican Americans were at the highest risk for the metabolic syndrome, with an age-adjusted prevalence of almost 32%.[18] Overall, the age-adjusted prevalence was similar for men and women. African American women, however, had an approximate 57% higher prevalence than their male counterparts. Mexican American women also had a disproportionate risk, about 26% higher than Mexican American men. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 5 According to the WHO, at least 200 million people worldwide have IGT.[25] Over the course of 5 to 10 years, approximately 40% of these individuals will progress to diabetes; the remainder will revert to normal glucose tolerance or will persist with IGT. Obesity is Central to Mechanisms of the Metabolic Syndrome Insulin resistance, often the first clinical marker of the metabolic syndrome, involves an overproduction of glucose by the liver, impaired peripheral glucose utilization, and an increased breakdown of fat, or lipolysis, leading to elevated levels of free fatty acids. Abnormal fatty-acid metabolism and visceral adiposity are known to play important roles in the metabolic syndrome.[25-27] Visceral adipose tissue is defined as adipose tissue located in the deep region of the abdomen. Deep visceral adipose tissue is relatively insensitive to the action of insulin and therefore undergoes lipolysis, breaking down triglycerides to form free fatty acids. In the liver, these free fatty acids drive glucose production. In addition, free fatty acids are used in the liver to form triglycerides, thereby driving the production of very lowdensity lipoproteins (VLDLs). In addition, free fatty acids cause insulin resistance in pancreas and skeletal muscle.[26] Free fatty acid elevation thus mediates resistance to insulin at all 3 tissue sites. Indeed, studies show that obese individuals with high levels of visceral adipose tissue have a much greater insulin response to oral glucose tolerance tests compared with obese people who have little visceral adipose tissue.[28,29] Insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia are established features of obesity. In Pima Indians, insulin sensitivity has been shown to decline with increasing BMI.[30,31] While both genes and environment influence the development of insulin resistance, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle have been shown to be the primary causes of insulin resistance, IGT, and type 2 diabetes.[32,33] In general, normoglycemia progresses to IGT, primarily due to increasing insulin resistance.[34] Individuals adapt to increasing insulin resistance with increased beta-cell mass and increased insulin secretion.[35] Both obese and insulin-resistant individuals have been shown to have compensatory hyperinsulinemia in the fasting and postprandial state.[36] Progression to diabetes occurs when beta cells cannot secrete enough insulin to compensate for the insulin resistance.[35-40] As a result, postprandial and fasting glucose levels increase, leading to IGT and/or the metabolic syndrome, and eventually to full-blown diabetes. Gradations of Cardiovascular Risk in Insulin Resistance The dyslipidemia, hypertension, glucose intolerance, and hypercoagulability caused by insulin resistance predispose an individual not only to diabetes, but also to coronary artery disease, MI, and stroke. Haffner and colleagues[41] conducted a retrospective analysis of the data from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S), the first secondary prevention study showing that 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 6 CoA) reductase inhibitors (commonly known as statins) substantially reduce all-cause mortality as well as cardiovascular events and mortality. Data analysis revealed a clear gradation in risk of major CHD events depending upon levels of fasting glucose. The portion of major CHD events increased from 25% among individuals with normal fasting glucose to almost 50% for people with a known history of diabetes. Despres and colleagues[42] examined the relationship between fasting insulin levels and the risk of ischemic heart disease in men aged 45 to 76 who did not have diabetes. The fasting plasma insulin concentrations in 91 patients who had experienced an ischemic event were compared with concentration in 105 controls. At baseline, fasting plasma insulin concentrations were 18% higher in the case patients than in the controls (P < .001). In addition, fasting insulin concentration was directly associated with the risk of ischemic heart disease. The Honolulu Heart Study similarly demonstrated a direct relationship between increasing postchallenge glucose concentration and CHD.[43] More than 6000 nondiabetic men aged 45-70 years were followed for 12 years. The rate of fatal CHD and total CHD (defined as total CHD and nonfatal MI) increased directly with postchallenge glucose concentration. Men in the fourth quintile of postchallenge glucose (157-189 mg/dL) had twice the age-adjusted risk of fatal CHD compared with those in the lowest quintile (40-115 mg/dL). Reducing CVD Events in the Metabolic Syndrome The well-established link between obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and CVD make intervention in this population crucial to improving public health. Treatment of 3 main disorders has been proven to reduce cardiovascular events in this high-risk group: hypertension, dyslipidemia, and hypercoagulability. In addition, because obesity, particularly central obesity, is at the fulcrum of the metabolic syndrome, any successful approach in this population must effectively deal with the issue of obesity. As a result, all pharmacologic interventions should be complemented with lifestyle approaches to promote weight loss. Hypertension Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) of > /= 140 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of >/= 90 mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensive drugs. [1] The relationship between SBP and DBP and cardiovascular risk is well established: Increases in DBP and SBP have been shown to be directly and continuously associated with increases in CVD risk.[44,45] Hypertensive individuals with 1 or more major CVD risk factors make up the bulk of the hypertensive population.[46] Specifically, hypertension is prevalent among people with the metabolic syndrome. Exercise and weight loss measures are no longer recommended for 6 to 9 months before treating with antihypertensive medications in these high-risk patients. Rather, guidelines now advise clinicians to consider Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 7 hypertensive drugs as primary therapy.[1] Indeed, while concomitant lifestyle modifications should be strongly recommended, their implementation should not delay the initiation of pharmacologic therapy. A number of large studies in diabetic persons with hypertension show important benefits in CVD outcomes from lowering blood pressure.[47-49] In the UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group, tight blood pressure control resulted in considerable clinical benefits for diabetic patients.[47] Patients assigned to the tight blood control group (mean, 144/82 mm Hg) had a 24% reduction in any diabetes-related end point, a 56% reduction in heart failure, and a 32% reduction in diabetes-related deaths compared with patients assigned to less the aggressive blood pressure control group (mean, 154/87 mm Hg) The percent risk reduction was similar in patients treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or a beta-blocker.[47] The Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) trial[48] examined the effects of blood pressure lowering on more than 18,000 hypertensive patients, 1501 with diabetes. Study results showed that aggressive DBP lowering to levels < 85 and 80 mm Hg was associated with a 51% reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular events (P = .005) and a 43% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular mortality (P = .016). Most patients required a combination of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (DCCBs) plus ACEinhibitors or beta-blockers to achieve these DBP levels. The HOPE Study investigators examined the effects of ACE inhibitors on cardiovascular and renal disease in a diabetic subpopulation of 3577 individuals.[49] Compared with patients taking placebo, subjects assigned to ACE inhibitor therapy experienced a 24% risk reduction in total mortality, a 37% risk reduction in cardiovascular death, and a 22% risk reduction in MI. Some evidence suggests that treatment with angiotensin II receptor antagonists results in a greater cardiovascular risk reduction in hypertensive patients compared with betablocker therapy.[50-52] Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension Study (LIFE) investigators randomized 9193 hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) to receive the angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker losartan or the beta-blocker atenolol.[51] While the drugs were equally effective in reducing SBP and DBP, they had significantly different effects on CVD outcome measures. After an average clinical follow-up of 4.8 years, patients in the losartan group were afforded a 13%reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke (P = .021) and ; the risk reduction in fatal/nonfatal stroke in the losartan group vs the atenolol group was 25% (P = .001). Of interest, losartan therapy was associated with a 25% risk reduction in the development of newonset diabetes compared with atenolol therapy (P = .001) In addition, patients in the losartan group experienced approximately a 2-fold greater ECG-LVH regression compared with those in the atenolol group. In a subset of 1195 patients with diabetes, there was a 39% risk reduction in all-cause mortality (P = .02) compared with patients treated with atenolol.[52] Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 8 Lifestyle modifications (Table 2) have also been shown to be effective methods of reducing blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors.[53] Even when lifestyle changes are not sufficient to adequately control hypertension, patients who adopt these changes may require fewer and lower doses of antihypertensive medications. [44,45] In addition, these healthy habits may actually prevent hypertension in the normotensive population.[54-58] Table 2. Recommended Lifestyle Modifications Lose weight if overweight Limit alcohol intake to no more than 1 oz ethanol (eg, 24 oz beer, 10 oz wine, or 2 oz of 100-proof whiskey) per day, or 0.5 oz ethanol per day for women and lighter-weight people Increase aerobic physical activity to 30-45 minutes per day, most days of the week Reduce sodium intake to no more than 100 mmol per day (2.4 g sodium or 6 g sodium chloride) Maintain adequate intake of dietary potassium at a level of approximately 90 mmol per day Maintain adequate intake of dietary calcium and magnesium Stop smoking Reduce intake of dietary saturated fat and cholesterol Modified from: Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. NIH Publication No. 98-4080, November 1997. Excess body weight is an important modifiable risk factor in hypertension. Body mass index values >/= 27 and waist circumferences >/= 34 inches in females or >/= 39 inches in males are all associated with increased risk of hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and CHD mortality.[59] Weight reduction of as little as 10 pounds (4.5 kg) has been shown to reduce blood pressure in a large percentage of overweight people with hypertension. [59-64] Furthermore, weight loss can boost the effect of concurrent antihypertensive agents and reduce concomitant CVD risk factors.[62] As a result, guidelines recommend that every overweight hypertensive patient be placed on a custom weight-loss program.[1] Aerobic activity coupled with a low-fat, low-cholesterol hypocaloric diet with restricted sodium is integral to any weight loss plan. Dyslipidemia The link between increasing LDL cholesterol and CHD risk is well established. In addition, clinical trials clearly show that LDL-lowering therapy reduces the risk for CHD. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 9 ATP III places increased importance on primary prevention of dyslipidemia in patients without established CHD who have multiple CVD risk factors.[2] The characteristic CVD risk factors of the metabolic syndrome combine to enhance risk for CHD at any given LDL cholesterol level.[18] Thus, after appropriate control of LDL cholesterol, ATP III recommends therapeutic lifestyle changes, including dietary changes combined with regular exercise and weight management, as first-line therapies for all risk factors associated with the metabolic syndrome. The guidelines recommend a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol. Individuals with significantly elevated LDL levels are advised to increase their fiber intake and to add plant sterol or stanol to their diet. Sedentary lifestyle is a major risk factor for CVD that boosts the risk of the lipid and nonlipid risk factors in the metabolic syndrome. Regular physical activity reduces VLDL levels, raises HDL cholesterol, and in some persons, lowers LDL levels.[61] As a result, regular physical activity should be a standard part of any cholesterol management program. In addition to LDL-cholesterol levels, ATP III recommends that clinicians consider the specifics of metabolic syndrome-associated dyslipidemia (ie, elevated triglycerides and low HDL-cholesterol levels) when constructing lipid-lowering treatment plans. Recent analyses indicate that triglycerides are an independent risk factor for CHD. [65-68] In practice, elevated serum triglycerides are most often observed in persons with the metabolic syndrome. Since they are the most accessible indicator of atherogenic lipoproteins, clinicians can monitor VLDL cholesterol levels during intervention. Thus, VLDL cholesterol can be a target of cholesterol-lowering therapy. According to ATP III, the sum of LDL+VLDL cholesterol is a secondary target of therapy in persons with high triglycerides. Analysis of data from 4S indicates that patients with impaired fasting glucose levels and those with diabetes can benefit from cholesterol-lowering drugs. Haffner and colleagues[41] retrospectively analyzed the effect of simvastatin therapy on CHD in patients with normal fasting glucose (n = 3237), impaired fasting glucose (IFG; n = 678), and diabetes mellitus (n = 483). Patients with IFG and diabetes treated with simvastatin experienced significant reductions in the risk of major coronary events, revascularizations, and total coronary mortality. Treatment strategies for hypertriglyceridemia vary depending upon the cause and severity. For high-risk patients, drug therapy is indicated to reduce elevated triglycerides. Weight loss and increased physical activity are considered essential components of achieving all non-HDL cholesterol goals. Low HDL cholesterol, defined by ATP III as < 40 mg/dL, has also been shown to be a strong independent predictor of CHD.[69-73] Some evidence suggests that lipid-lowering drugs such as fibrates can reduce the risk of stroke in patients with coronary heart disease and low levels of HDL cholesterol. For example, in the Veterans Affairs HDL Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 10 Intervention Trial (VA-HIT), more than 2500 men were randomized to gemfibrozil or placebo and were followed up for 5 years.[69,70] There was a high prevalence of the metabolic syndrome (obesity, type 2 diabetes, and hyperinsulinemia) in the study group. Patients in the gemfibrozil group experienced a relative risk reduction of 31% (95% CI, 2% to 52%, P =.036). However, due to insufficient evidence, the ATP III does not specify a goal for boosting HDL levels. Thus, in patients with the metabolic syndrome, the primary target of therapy is LDL cholesterol. Once appropriate LDL cholesterol levels have been achieved, weight reduction and increased exercise should be strongly recommended. Fibrates or nicotinic acid to increase HDL can be considered in patients with low HDL in combination with elevated triglycerides. Hypercoagulability Insulin-resistant patients have been shown to have high levels of circulating plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1), a protein that inhibits fibrinolysis.[74-77] Along with increases of Factor VII, a coagulation factor found in hypertriglyceridemic patients, PAI-1 is thought to play an important role in the hypercoagulability state so often observed in patients with the metabolic syndrome. In addition, some studies show that PAI-1 levels are associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease. Recently, Festa and colleagues[75] examined the concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and PAI-1 in 1047 nondiabetic subjects. The 144 patients who had developed diabetes at follow-up had higher initial levels of fibrinogen and PAI-1 than did subjects who remained diabetes-free. After adjusting for BMI and insulin, only PAI-1 remained significantly related to incident type 2 diabetes (P = .002). Thus, PAI-1 level may be helpful in determining the risk of diabetes and, by extension, the risk of CHD, in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Antiplatelet therapy has been shown in numerous multicenter interventional trials to reduce the rate of cardiovascular events in both nondiabetic and diabetic patients. [78-82] In 1994, results of the first publication of the Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration showed a risk reduction of 15% to 20% of MI in diabetic patients.[80] Results of the HOT trial showed aspirin therapy similarly reduced the risk of MI.[8,48] Other antiplatelet therapies such as glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors, fibrinogen, and adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonists have also proven effective at reducing the risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Impaired endothelial function is thought to play an integral role in the increased risk of CVD associated with insulin resistance. Studies show that patients with insulin resistance have abnormal nitric oxide-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and elevated plasma levels of PAI-1 and endothelin 1, as well as monocyte adhesiveness.[83] Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 11 Stühlinger and colleagues[84] recently studied the relationship between tissue insulin sensitivity and plasma levels of the nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), whose elevated levels had previously been shown to be associated with an increased risk of CVD.[85] Sixty-four healthy individuals without diabetes (48 with normal blood pressure and 16 with hypertension) were enrolled in the cross-sectional study. Seven insulin-resistant hypertensive patients were studied before and after administration of the insulin-sensitizing agent rosiglitazone. Plasma ADMA concentrations were positively associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic, normotensive subjects (P < .001). In addition, ADMA levels were positively correlated with fasting triglyceride levels, but not with LDL cholesterol levels. Of interest, plasma ADMA concentrations increased in insulin-resistant subjects independent of hypertension. Rosiglitazone treatment improved insulin and significantly reduced mean plasma ADMA concentrations in the 7 patients studied. Lifestyle Modification: The Key to Weight Loss Thanks in part to a greater understanding and awareness of the pivotal role obesity plays in CVD and in the metabolic syndrome, interventions have shifted away from weight management alone to a comprehensive program of lifestyle modification.[12,86] It is now recognized that overweight and obesity are the result of intricate interactions between social, behavioral, cultural, physiologic, metabolic, and genetic factors in association with a sedentary lifestyle and high-fat, energy-dense diet. Thus, lifestyle modification involving changes in dietary intake, physical activity, and behavior must all be part of the therapy regimen. The current gold standard for treating obesity involves an individualized combination of all of these components, with the addition of medication in some cases. Successful weight loss promotion in clinical practice is often challenging, if not frustrating. Recent clinical trials, nevertheless, show that modest yet meaningful and sustainable weight losses of 5% to 10% of basal body weight are achievable. In addition, a growing body of research supports the value of identifying and treating obesity in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Identifying High-Risk Patients According to the NHLBI, overweight is defined as a BMI of 25.0-29.9 kg/m2, while obesity is defined as a BMI of >/= 30.[12] Individuals with a BMI of 25-30 kg/m2 and comorbidities of obesity should be treated with diet, exercise, and behavior therapy. [12] For cases in which diet, exercise, and behavior therapy fail to achieve desired goals, medication can be considered. Pharmacotherapy is indicated in patients with a BMI of 30 kg/m2 or a patient with a BMI of 27-30 kg/m2 with comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, sleep apnea, or arthritis. Diabetes Prevention via Weight Loss Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 12 The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) was the first major clinical trial to show that diet and exercise delay the development of type 2 diabetes in a cohort of overweight patients with IGT.[87-91] Subjects were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 treatment groups: patients in 1 group were treated with intensive lifestyle intervention including diet and exercise, with the remaining patients divided into 2 masked medication treatment groups combining either metformin or placebo with standard diet and exercise recommendations. Subjects in the intensive-lifestyle group achieved a 58% reduction in their risk of developing type 2 diabetes. These subjects engaged in 30 minutes per day of moderate exercise and achieved a modest 7% average weight loss in the first year; they maintained an average 5% weight loss for the duration of the trial. Participants randomized to metformin therapy and given instruction on diet and exercise reduced their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 31%. Further analysis of DPP data will look at the effect of these interventions on risk factors for CVD. The Da Qing Study and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study had similar outcomes. [9295] Both groups studied the role of intensive lifestyle modification in preventing the progression from IGT to type 2 diabetes. Finnish researchers randomly assigned 523 overweight subjects with IGT to the intervention or control group. The goals of the intervention were a weight reduction of >/= 5%, a total fat intake of < 30% of total energy, saturated fat intake of < 10% of energy intake, a fiber intake of > 15 g per 1000 calories, and moderate exercise of >/= 30 minutes per day. The mean weight loss at the end of the first and second years was significantly greater in the lifestyle intervention group compared with the control group. By the end of year 2, the intervention group had lost a mean of 3.4 kg vs 0.8 kg in the control group. The risk of diabetes was reduced by 58% in the intervention group compared with the control group. These and a host of earlier studies show that a modest weight loss of 5% to 10% of basal body weight is associated with significant reductions in blood pressure, lipid levels, and mortality.[95-100] The benefits of weight loss include improved lipid profile, reduced blood pressure, better glycemic control, reduced left ventricular mass, and an overall improvement in CVD risk profile.[95-102] Thus, clinicians and patients should make efforts to embrace this achievable weight loss goal. Which Diets Work? While popular "fad" diets such as high-protein or low-carbohydrate diets often focus on manipulating specific food groups, healthy sustained weight loss is, in theory, much simpler. Body weight is determined by the relationship between calories consumed and calories expended. Thus, depending on an individual's weight, subtracting 500 to 1000 kcal/day from the diet is an integral part of any weight-loss program (Table 3).[12] Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 13 The quality, not just the quantity, of calories is important in weight loss and disease prevention. Fat intake, particularly saturated fat, should comprise < /= 30% of total calories. Patients should be counseled that reducing the percentage of dietary fat alone would not produce weight loss unless total calories are also reduced. Frequent followup and communication with the patients helps promote weight loss and maintenance. Physicians should also consider referring patients to registered dieticians for care and to organizations such as the American Heart Association (AHA) for further information and support. A more structured diet may be appropriate and effective for some patients. During the course of 1 week, a patient must face 21 breakfasts, 21 lunches, and 21 dinners. For some individuals, relying on liquid meal replacements or strict meals may help in weight loss and weight maintenance. Patients in the DPP were encouraged to refer to the Food Guide Pyramid and the National Cholesterol Education Program Step 1 diet in order to adhere to a low-calorie, low-fat diet.[87,103,104] Exercise: How Much? What Type? How much and what kind of exercise is needed? The Surgeon General, CDC, and AHA recommend a regular program of moderate-to-vigorous intense physical activity for an accumulated time of >/= 30 minutes a day.[61] Resistance training for 20-30 minutes twice a week is also strongly recommended, particularly for women, as it can aid in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. It is important to stress that reaping the benefits of exercise does not require a personal trainer or marathon running. Lifestyle activities such as taking the stairs instead of the elevator, raking leaves, doing housework, and brisk walking are all modes of physical activity that should be encouraged. A busy person need not exercise for 30 minutes at a time -- accruing three 10-minute segments is also beneficial. Can Physicians Really Help to Modify Behavior? One of the greatest challenges in treating overweight and obese patients is helping them set realistic, yet clinically meaningful weight loss goals of a 5% to 10% reduction in initial weight.[105-109] By focusing on clinical outcomes such as improved cholesterol levels, blood pressure, or self-esteem, clinicians can reinforce the importance of even modest weight losses. Furthermore, by making it clear to patients at the outset that they can expect to lose an average of 10% of their initial weight after 6 months will help temper lofty and unlikely weight-loss goals. The successful lifestyle intervention program employed in the DPP[87] relied on individualized one-on-one counseling detailing the basics of diet, exercise, and behavior modification. Guidelines recommended that case managers meet with study participants weekly for 20 of 24 weeks, since studies show that more frequent patient contact promotes weight loss. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 14 Physicians should expect patients to falter in their efforts to employ lifestyle modifications. Encouraging individuals to set specific, realistic goals for positive change can help promote adherence. Close monitoring of patient weight-loss goals is also important. In addition, referring patients to weight control or wellness clinics as well as to dieticians and nutritionists can help promote adherence to lifestyle modification. Pharmacotherapy: When Diet and Exercise Aren't Enough When adequate weight reduction is not achieved by lifestyle changes, weight-loss drugs can be considered. Even when pharmacologic intervention is deemed appropriate, lifestyle modification can improve the efficacy of available agents.[110,111] Weight-loss drugs are recommended in individuals with a BMI >/= 30 kg/m 2 and no concomitant obesity-related factors or disease.[111] Patients who have serious risk factors and diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, CHD, type 2 diabetes, or sleep apnea should be considered for pharmacotherapy at a BMI of 27-29.9 kg/m2. Currently, 2 drugs are approved for long-term treatment of obesity: orlistat and sibutramine. Orlistat Individuals who need help in keeping dietary fat intake to 30% of calories may benefit from the lipase inhibitor orlistat. Orlistat inhibits the action of intestinal lipase, thus reducing dietary fat absorption by up to 30%. In clinical trials, it produces approximately 5% to 10% loss of initial body weight.[112,113] When prescribed in combination with a weight-maintenance diet, orlistat results in better maintenance of weight loss compared with placebo.[113] Because orlistat reduces absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (especially vitamin D) and beta-carotene, vitamin supplementation is recommended during therapy. The adverse effects of orlistat are primarily gastrointestinal and are intensified by consumption of high-fat foods. In obese people with the metabolic syndrome, orlistat therapy resulted in weight loss associated with a reduction in plasma insulin and CHD risk factors.[114-116] Pooled data from 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials showed that orlistat combined with dietary interventions led to a greater rate of glycemic normalization compared with the placebo group.[115] Sibutramine For patients who seem to be having trouble with satiety, sibutramine might help promote weight loss. Sibutramine can help reduce appetite and lessen the preoccupation with food, giving patients a better chance at complying with dietary guidelines. The most frequently reported adverse effects include dry mouth, anorexia, headache, insomnia, and constipation. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 15 Sibutramine inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, and, to a lesser extent, dopamine. In clinical trials, it produces a dose-dependent 5% to 10% decrease in body weight. Treatment with sibutramine accompanied by dietary guidance has been shown to result in significantly greater weight loss than dietary advice alone.[117] Weight loss with sibutramine has also been shown to be associated with favorable changes in CVD risk factors, including plasma lipids, uric acid, and glucose.[118-123] James and colleagues[124] conducted a multicenter, double-blind trial on the effectiveness of sibutramine in maintaining weight loss over 2 years. In the first step of the study, 605 obese patients were randomized to a hypocaloric diet plus 10 mg/day sibutramine or to diet plus placebo. Next, the 467 patients who had lost more than 5% of their basal body weight were randomized to 10 mg/day sibutramine or placebo for an additional 18months. Forty-two percent of the sibutramine group and 50% of the placebo group dropped out of the study. Of those who remained, 43% of sibutramine-treated individuals maintained >/= 80% of their original weight loss over 2 years compared with 16% of the placebo group (P < .001). Patients had substantial decreases in the levels of triglycerides, VLDL cholesterol, insulin, C peptide, and uric acid. Only patients in the sibutramine group sustained these changes over 2 years. In addition, HDL cholesterol concentrations rose significantly more in the second year in the sibutramine group (20.7%) compared with the placebo group (11.7%). In this and other studies, sibutramine treatment was associated with small mean increases in blood pressure and heart rate. Thus, it is recommended that blood pressure and heart rate be assessed before prescribing or increasing the dose of sibutramine. Phentermine While it is only approved for 3-month usage, phentermine remains the most popular weight loss drug. Clinical trials have shown that treatment with phentermine results in a 5% to 15% weight loss in 60% of patients if given daily or intermittently.[125-127] Phentermine is cheaper than sibutramine and orlistat. Its biggest drawbacks are that it is indicated only for short-term treatment and tolerance often develops. Like all noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, phentermine's side effects include dry mouth, constipation, sleep disturbance, and increased blood pressure. When taken in conjunction with a hypocaloric diet, more weight loss is seen. Putting It All Together for the Best Results Clinicians should prescribe weight-loss-promoting drugs in concert with diet, exercise, and behavior modification. A recent study demonstrates the efficacy of this approach. Wadden and colleagues[111] compared the effects of 3 approaches to weight loss. Fiftythree women were randomized to 1 of 3 groups: sibutramine alone; sibutramine and Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 16 lifestyle modification including a 1200-1500 kcal/day diet (drug-lifestyle); or sibutramine, lifestyle modification, and a portion-controlled diet (1000 kcal/day) diet for the first 4 months (drug-lifestyle-diet). At month 12, patients treated with the drug alone lost a mean of 4.1% of their initial body weight; patients in the drug-lifestyle group lost a mean of 10.8% of their initial body weight; and patients in the drug-lifestyle-diet group lost a mean of 16.5% of their initial body weight. Women in both lifestyle intervention groups achieved a greater percentage of their expected weight loss than those in the drug-alone group (P < .05). Significant reductions in triglyceride and LDL levels were also observed at 12 months. Thus, the addition of group lifestyle modification to the pharmacologic management of obesity significantly improved weight loss. Surgical Interventions for Weight Loss Bariatric surgery can be considered in patients with morbid obesity, defined as a BMI of >/= 40 kg/m2, or in individuals who exceed their ideal body weight by >/= 100 pounds.[118,119,128] Patients with a BMI between 35 and 40, or those who exceed their ideal body weight by >/= 85 pounds must have associated comorbidities to warrant the risk associated with bariatric surgery. The 2 widest classifications of bariatric surgery include vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG) and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (GBP).[119,120] Studies show that VBG results in a weight loss of 25% to 50% in 50% to 80% of patients 5 years after surgery.[121,122] GBP, the most widely performed procedure, is considered the "gold standard" in bariatric surgery. It achieves a more sustained weight loss compared with that resulting from VBG: a 40% to 85% decrease in excess body weight in > 90% of patients.[123,129] In most cases, weight loss is maintained.[130,131] Cardiovascular Disease Trials: Where Are the Data on Obesity? Over the last 3 decades, vast numbers of clinical trials have led to an explosion of knowledge affecting the way cardiovascular disease is treated and prevented. The increasing use of ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, and statins in ever healthier patient populations are excellent examples of the cumulative effect of small and large trials on clinical practice.[132-140] This research has identified strategies to prolong survival, reduce morbidity, and improve QOL in patients with CVD. Small clinical trials are useful for examining physiologic mechanisms and determining the effects of drugs on cardiovascular symptoms. These trials demonstrate beneficial effects on surrogate outcomes such as changes in exercise time or changes in symptoms. Yet it is always important to keep in mind that surrogate outcomes are just that -- surrogate. Thus, beneficial effects on surrogate outcomes don't necessarily translate into beneficial effects on clinical events or reductions in mortality and morbidity. Nevertheless, data from small clinical trials are vital to the process of designing larger trials to assess drug effects on clinical events. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 17 Large clinical trials typically examine mortality and morbidity events. Because of the large sample size, these trials can detect even moderate treatment effects. It is important to note that the progression of CVD involves a complex set of interrelated factors all contributing to the clinical condition. Thus, even when a therapy has been shown to positively affect clinical outcomes, the nature of the disease process limits the impact of the therapy. As such, any particular therapy can only be expected to have a moderate effect on the clinical picture of disease. Obesity and CVD: Surrogate Data vs Cardiovascular Clinical Outcomes The relationship between increasing body mass index and CVD risk factors has been well established. For example, a 10-kg weight gain produces an approximate 3-mm rise in systolic blood pressure and a 2-mm rise in diastolic blood pressure, and increases the risk of CHD and stroke. Obesity is also an independent predictor of CHD, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Furthermore, obesity significantly and independently correlates with increases in LV mass. Indeed, surrogate data show that weight loss leads to improvements in dyslipidemia, hypertension, insulin resistance, and abdominal obesity and LV mass.[141-146] These improvements suggest that weight loss should also beneficially affect clinical outcomes. Unfortunately, surrogate outcomes don't always predict clinical outcomes. To date, there have been no large, prospective, randomized, controlled trials looking at the effects of weight loss on cardiovascular clinical outcomes. There are, in fact, some observational studies or meta-analyses suggesting that weight loss or fluctuations may actually increase cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.[147-149] Only large, long-term, randomized trials will answer this important question. References 1. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The Sixth Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National High Blood Pressure Education Program. NIH Publication No. 98-4080; November 1997. 2. Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). National Cholesterol Education Program. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Institutes of Health. NIH Publication No. 01-3670; May 2001. 3. Lamarche B, Tchernof A, Mauriege P, et al. Fasting insulin and apolipoprotein B levels and low-density lipoprotein particle size as risk factors for ischemic heart disease. JAMA. 1998;279:1955-1961. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 18 4. Lamarche B, Tchernof A, Moorjani S, et al. Small, dense low-density lipoprotein particles as a predictor of the risk of ischemic heart disease in men. Prospective results from the Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Circulation. 1997;95:69-75. 5. Kannel WB. Potency of vascular risk factors as the basis for antihypertensive therapy. Eur Heart J. 1992;13(suppl G):34-42. 6. Kannel WB. Blood pressure as a cardiovascular risk factor. JAMA. 1996;275:1571-1576. 7. Neaton JD, Wentworth D, for the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Serum cholesterol, blood pressure, cigarette smoking, and death from coronary heart disease. Overall findings and differences by age for 316 099 white men. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:56-64. 8. Reaven GM, Lithell H, Landsberg L. Hypertension and associated metabolic abnormalities -- the role of insulin resistance and the sympathoadrenal system. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:374-381. 9. Cohn JN. Arteries, myocardium, blood pressure and cardiovascular risk: towards a revised definition of hypertension. J Hypertens. 1998;16(12 pt 2):2117-2124. 10. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults: United States. Hyattsville, Md; 1999. 11. World Health Organization. Definition, Diagnosis, and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Department of Noncommunicable Diseases. Geneva, Switzerland; 1999. 12. National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: The Evidence Report. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, NIH, NHLBI; 1998. 13. United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. 14. Wolf A, Colditz G. Current estimates of the economic cost of obesity in the United States. Obes Res. 1998;6:97-106. 15. Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight change and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:214-222. Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 19 Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD Assessment 1. Traditional CVD risk factors include: a. Hypertension b. Dyslipidemia c. Cigarette smoking d. All of the above 2. CVD is a progression that begins and continues through a complex interaction between ______. a. Genetics and diet b. Genetics and the environment c. Exercise and the environment d. Diet and exercise 3. _____ tends to cluster in patients with other cardiovascular risk factors, such as abnormalities of glucose, insulin, and lipoprotein metabolism. a. Hypotension b. Hypertension c. Obesity d. Diabetes 4. _______ patients are more likely to be obese, to smoke cigarettes, and to have a family history of CVD compared with their normal counterparts. a. Elderly b. Overweight c. Hypertensive d. All 5. At its essence, the ______ is a cluster of characteristics that together increase the risk of diabetes and CHD in addition to numerous other health problems. a. Insulin syndrome b. Digestion syndrome c. Metabolic syndrome d. Dyslipidemia syndrome 6. _______, often the first clinical marker of the metabolic syndrome, involves an overproduction of glucose by the liver, impaired peripheral glucose utilization, and an increased breakdown of fat, or lipolysis, leading to elevated levels of free fatty acids. a. Glucose resistance b. Insulin resistance c. Lipid resistance Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD 20 d. Glucagon resistance 7. Hypertension is defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) of > /= ___ mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of >/= ____ mm Hg, or the use of antihypertensive drugs. a. 150; 90 b. 140; 90 c. 130; 80 d. 130; 90 8. _______ in DBP and SBP have been shown to be directly and continuously associated with increases in CVD risk. a. Increases b. Decreases c. Rapid changes d. Any of the above 9. ________ reduces VLDL levels, raises HDL cholesterol, and in some persons, lowers LDL levels.[61] As a result, it should be a standard part of any cholesterol management program. a. Eating less b. Regular dieting c. Regular physical activity d. Prescription drug use 10. Impaired ________ function is thought to play an integral role in the increased risk of CVD associated with insulin resistance. a. Epithelial b. Endothelial c. Tunica media d. Tunica externa Florida Heart CPR* Diet, Weight Loss and CVD