THW Ban Animal Testing - Propostition

advertisement

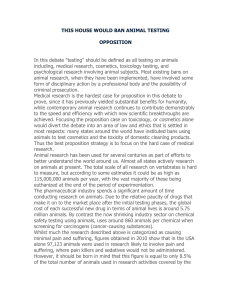

THIS HOUSE WOULD BAN ANIMAL TESTING PROPOSITION In this debate "testing" should be defined as all testing on animals including, medical research, cosmetics, toxicology testing, and psychological research involving animal subjects. Most existing bans on animal research, when they have been implemented, have involved some form of disciplinary action by a professional body and the possibility of criminal prosecution. Medical research is the hardest case for proposition in this debate to prove, since it has previously yielded substantial benefits for humanity, while contemporary animal research continues to contribute demonstrably to the speed and efficiency with which new scientific breakthroughs are achieved. Focusing the proposition case on toxicology, or cosmetics alone would divert the debate into an area of law and ethics that is settled in most respects: many states around the world have instituted bans using animals to test cosmetics and the toxicity of domestic cleaning products. Thus the best proposition strategy is to focus on the hard case of medical research. Animal research has been used for several centuries as part of efforts to better understand the world around us. Almost all states actively research on animals at present. The total scale of all research on vertebrates is hard to measure, but according to some estimates it could be as high as 115,000,000 animals per year, with the vast majority of these being euthanized at the end of the period of experimentation. The pharmaceutical industry spends a significant amount of time conducting research on animals. Due to the relative paucity of drugs that make it on to the market place after the initial testing phases, the global cost of each successful new drug in terms of animal lives is around 5.75 million animals. By contrast the now shrinking industry sector on chemical safety testing using animals, uses around 860 animals per chemical when screening for carcinogens (cancer-causing substances). Whilst much the research described above is categorized as causing minimal pain and suffering, figures obtained in 2010 show that in the USA alone 97,123 animals were used in research likely to involve pain and suffering, where pain killers and sedatives would not be administered. However, it should be born in mind that this figure is equal to only 8.5% of the total number of animals used in research activities covered by the US Animal Welfare Act - but the act does not cover mice, rats, birds or fish. The differences between us and other vertebrates are a matter of degree rather than kind. Not only do they closely resemble us anatomically and physiologically, but so too do they behave in ways which seem to convey meaning. They recoil from pain, appear to express fear of a tormentor, and appear to take pleasure in activities; a point clear to anyone who has observed the behavior of a pet dog on hearing the word “walk”. Our reasons for believing that our fellow humans are capable of experiencing feelings like ourselves can surely only be that they resemble us both in appearance and behavior (we cannot read their minds). Thus any animal sharing our anatomical, physiological, and behavioral characteristics is surely likely to have feelings like us. If we accept as true for sake of argument, that all humans have a right not to be harmed, simply by virtue of existing as a being of moral worth, then we must ask what makes animals so different. If animals can feel what we feel, and suffer as we suffer, then to discriminate merely on the arbitrary difference of belonging to a different species, is analogous to discriminating on the basis of any other morally arbitrary characteristic, such as race or sex. If sexual and racial moral discrimination is wrong, then so too is specieism. Animal research, by its very nature necessitates harm to the animals. Even if they are not made to suffer as part of the experiment, the vast majority of animals used, must be killed at the conclusion of the experiment. With 115 million animals being used in the status quo this is no small issue. Even if we were to vastly reduce animal experimentation, releasing domesticated animals into the wild, would be a death sentence, and it hardly seems realistic to think that many behaviorally abnormal animals, often mice or rats, might be readily moveable into the pet trade. It is prima fasciae obvious, that it is not in the interest of the animals involved to be killed, or harmed to such an extent that such killing might seem merciful. Even if the opposition counterargument, that animals lack the capacity to truly suffer, is believed, research should nonetheless be banned in order to prevent the death of millions of animals. As experimenting on animals is immoral we should stop using animals for experiments. But apart from it being morally wrong practically we will never know how much we will be able to advance without animal experimentation if we never stop experimenting on animals. Animal research has been the historical gold standard, and in the case of some chemical screening tests, was for many years, by many western states, required by law before a compound could be released on sale. Science and technology has moved faster than research protocols however, and so there is no longer a need for animals to be experimented on. We now know the chemical properties of most substances, and powerful computers allow us to predict the outcome of chemical interactions. Experimenting on live tissue culture also allows us to gain insight as to how living cells react when exposed to different substances, with no animals required. Even human skin leftover from operations provides an effective medium for experimentation, and being human, provides a more reliable guide to the likely impact on a human subject. The previous necessity of the use of animals is no longer a good excuse for continued use of animals for research. We would still retain all the benefits that previous animal research has brought us but should not engage in any more. Thus modern research has no excuse for using animals. It is possible to conceive of human persons almost totally lacking in a capacity for suffering, or indeed a capacity to develop and possess interests. Take for example a person in a persistent vegetative state, or a person born with the most severe of cognitive impairments. We can take three possible stances toward such persons within this debate. Firstly we could experiment on animals, but not such persons. This would be a morally inconsistent and specieist stance to adopt, and as such unsatisfactory. We could be morally consistent, and experiment on both animals and such persons. Common morality suggests that it would be abhorrent to conduct potentially painful medical research on the severely disabled, and so this stance seems equally unsatisfactory. Finally we could maintain moral consistency and avoid experimenting on the disabled, by adopting the stance of experimenting on neither group, thus prohibiting experimentation upon animals. Most countries have laws restricting the ways in which animals can be treated. These would ordinarily prohibit treating animals in the manner that animal research laboratories claim is necessary for their research. Thus legal exceptions such as the 1986 Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act in the UK exist to protect these organizations, from what would otherwise be a criminal offense. This creates a clear moral tension, as one group within society is able to inflect what to any other group would be illegal suffering and cruelty toward animals. If states are serious about persuading people against cock fighting, dancing bears, and the simple maltreatment of pets and farm animals, then such goals would be enhanced by a more consistent legal position about the treatment of animals by everyone in society.