Center: Exit Wounds

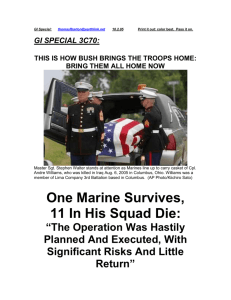

advertisement

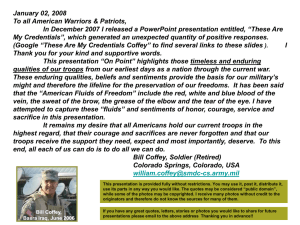

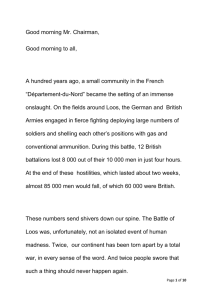

Exit Wounds: The Myth of Homecoming During The Battle of the Bulge, the bloodiest battle that U.S. forces experienced in World War II, a young American soldier stationed with his combat battalion in France, sickened from sleeping in wet and muddy foxholes next to the corpses of his friends and eating rancid food, determined he required a vacation. He left his regiment without orders or permission, and hiked into German occupied Nancy, France, where he rested and quietly swam in the municipal pool. A sign read, “Nur Offizier” (Officers Only). Two weeks later, the weary Battle of the Bulge survivor walked back through enemy territory to resume his position on the front lines. The soldier had been awarded three purple hearts and a bronze star, but his acts of courage did not sway his superiors from arresting the AWOL soldier, and after serving in combat for the remainder of the war, was later court martialed. This soldier was my father. As I was growing up, in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the stories he told were generic, and agreed with the choppy newsreels and movies I was raised on. His stories seemed to support the nobility of serving your country as a soldier and that it was right to fight in a war. When I approached eighteen in 1968, and the Vietnam War was raging, my dad was dead set against sending me to war. He said, “The one thing that I learned from volunteering into the Army was, never volunteer for anything.” I got enough subtle messages over the years that maybe war wasn't all it was cracked up to be. Before his death, more than sixty after the Battle of the Bulge, my father finally began sharing more intimate, painful wartime experiences, as we walked together around our North Portland neighborhood where we lived most of our lives. The walks were long even though the distances were short. His walker rattled and his feet barely cleared the cracks in the sidewalk as we ambled along. His memory ebbed and flowed, as past blurred with the present, and the new stories revealed a darker side of war. It's clear to me now the man who gave me everything he was capable of, did his best to spare me and everyone else the reality of war. After the war ended, his generation was told to "man-up," buy a house and pretend that nothing happened. Despite all he experienced, and the pain he was withholding, he was a loving, generous father. The war had always been with him privately, but at the end of his life he began to talk about what really happened at the Battle of the Bulge as we walked, as it faded into his fog of war. My father’s revelations gave me an idea about doing a soldiers' oral history of the current war in Iraq and Afghanistan. I feel that soldiers need to tell their stories and we need to hear them. The soldiers that I have been interviewing and photographing have been generous with their stories and intimate feelings. They have taught me what it is to descend into hell and then try to find their way home. Many of the details of my father’s experience are lost with him, but as I chronicle the lives of today’s young soldiers, their story is his story. I hope they can find their way out of the fog. Sixty years is way too long to keep a secret. --Jim lommasson "I wouldn't wish war on my worst enemy." – Marine John Fett to his mother. "Before we as a people send our youth into war, we have a responsibility and an obligation to fully understand the enormity of what it is we ask them to do. We are asking them to die. We are sending them into horrible situations in which they face horrible decisions and partake in horrible acts. To truly honor the warrior every patriotic American must bear witness to their stories and their pain." – Mary Geddry mother of twice deployed Marine John We find that we do not want to tell our stories to people who are incapable of hearing our stories with their heart. Please, do not ask us if we’ve killed anybody. This is the number one question posed to us and it reflects the morbid curiosity of those wanting to be entertained. We cannot, do not, and will not bring upon others the burdens that we’ve shouldered. It isn’t who we are. And were we to want to bridge that gap with a wife, a mother or father… how could we contaminate the hearts of our loved ones with such as we’ve known? How can we tell those that love us the things we’ve done, the choices we’ve made? And if we do not, how can we ask for simple acceptance if they know not what secrets we keep in our hearts? Listen to our stories with your heart. Allow us the right to weep as Achilles wept for Patroclus. Allow us our confusion and anger. Let us feel that we are part of your community… our community. It takes more than a yellow ribbon on a car. Next veteran you see, of any war, go up to him or her and offer a hug or a handshake. It takes a nation to send troops off to war. It takes a nation to bring them back. "What will haunt me for the rest of my life is when we took POW’s (prisoners of war). I had so much hatred for them. I didn’t care if they lived or died. I will not go into details on what was done for fear of the law, but things still haunt me. I remember pulling guard on an insurgent that was about to be turned over to the local war lords. He was flex cuffed and shaking so bad, I gave him a smoke and started small talk. At one point I did a little hand gesture to tell him that he was about to get his head cut off, then I took the smoke from him and said something hateful. Things like that still bother me." "I did not like fighting in Iraq, I did not believe in why we where there. I went because I felt like I owed my friends that were killed over there. They had everything to live for; family, wife, kids. I had none of that, so why didn’t God take me?" – Arturo Franco "I have five gold stars tattooed on my shoulder. That’s five bothers of mine who were killed by these people. It’s been a pretty messed up period in my life lately. My brigade is shipping out to Iraq again and it’s tearing me up. It’s killing me, being stuck here and not going, knowing that my friends are going to face the hell of war and I won’t be there wit them. Sometimes being left behind is a fate worse than bearing the scars that war produces on the body and soul. I pray to God I don’t have to tattoo any more stars." – Miah Washburn "So, I just had a conversation with the Bank about my college loan. I explained my situation and my hardship being a disabled combat veteran and finding a job and paying back my loan. I asked them if there were any options of getting a deferment or forbearance. They explained to me that, they do not offer such privileges to anyone. They told me I have 16 days to make a payment or my account will be handed over to a collecting agency. Then I asked them what would be a way to make sure that my parents don't end up stock with my debt, they did not have an answer, so, I asked them what would happen if I blew my brains out, only then they said that my loan would be forgiven. So, Veterans, thank you for your sacrifice and thanks for the bailouts that the has been receiving from our tax money and the only way we can help you, only if you blow your brains out!!!!!” “And I'm proud to be an American, where at least I know I'm free, AND I WONT FORGET THE MEN WHO DIED WHO GAVE THEIR LIFE FOR ME AND I GLADLY STAND UP............" – Sergio “The convoy killed a girl and two goats. I went out with Civil Affairs and we paid off the family. The going rate for the goat was twice that of the daughter. I think they got $2000 for the whole package. It was horrible.” – Ash Woolson "If armed dudes from a foreign country walked through the park blocks, we would be scared and offended, too. We know the realities of clearing house-to-house and taking people’s weapons away. We would never allow this in the US." – Shawn McKenzie. “I think [vets] need to tell what hell guys go through over there, I don't think they really understand how horrible it it is. You might just have to talk to somebody like Shawn and they might tell you what it's really like. It isn't published enough. It might scare us, but it might make people get mad and demand something be done.” – Shawn's grandmother Violet "Being thanked for doing something for America feels very awkward. I never felt that I was doing anything for America. I was doing it for the people that I was there with. I will happily accept thanks for the job that I did for the soldiers. I want people to know most returning veterans don't always feel good about what they were involved in. Vets don't always feel good about what they've done. Not everyone wants to be regarded as a hero, or welcomed home as if there achieved something. Or that they should be thanked when they've experienced things that should not have happened. If we are going to commit ourselves to a conflict, we need to commit ourselves to the consequence. People need to share that burden, and listen to the vets." – Myla "Growing up, my dream was to be in the Army. All I ever wanted to do was to be in the Army and lead men into combat. I got 30 seconds of my dream, I'd give my other leg to live it again." – Lucas Wilson "“People look at the Nazi concentration camps and wonder, how can you do something like that? It’s really easy. It’s a simple thing. You make one wrong decision and you spend the rest of your life explaining that decision. I’ve barely made any choices in my life, and then I ended up working in a concentration camp. You wake up every day, put your boots on and go to work at the concentration camp.” – Christopher Arendt former Guantanamo guard Photos taken by service members during deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan.