Appendix B: Lyon historiography

advertisement

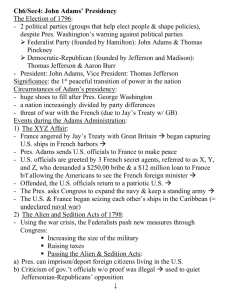

Scott Ackerman 10/20/10 John Adams in the Role of Joe McCarthy: Reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts in Historiography Writing in 1802, author John Wood offered a bold prediction for posterity. In his work The Suppressed History of the Adams Administration Wood wrote that “the prosecutions of Lyon and Callender, of Cooper and Holt were the best commentary on the sedition law” because “the names of these gentleman will be quoted in both support of liberty of the press, and of the tyranny of Mr. Adams.”1 The irony is amusing with hindsight. Adams is mostly remembered for his relentless defenses of liberty during the American Revolution, while Lyon, Callender, Cooper and Holt have been largely forgotten. Although Wood proved to be a poor prognosticator, in several crucial respects he proved to be an able chronicler. An unabashed Jefferson partisan, Wood’s narrative carefully detailed the larger political context of the Sedition laws in order to portray the Federalist as scheming political demagogues. Despite his partisan intent, or perhaps because of it, Wood’s narrative clearly reflected the larger political meanings of Alien and Sedition Acts. Unfortunately, until recently two major themes have proved remarkably persistent in the way historians have depicted popular reaction to the Alien and Sedition Act; a tendency to frame popular reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts as a debate over free speech and civil liberties, thus partially obscuring the larger context of 1790’s political culture, and a tendency to paint hagiographical portraits of the Republicans, and consequently rendering their overall depiction of reaction to the Alien and Sedition Act lopsided. The tendencies to both frame popular reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts as a debate over free speech and civil liberties, as well as treat the Republicans uncritically, originated most forcefully with John C. Miller’s Crisis of Freedom, The Alien and Sedition Acts (1951) and James Morton Smith’s Freedom’s Fetters, The Alien and Sedition Laws and American Civil Liberties (1956). 1 John Wood, The Suppressed History of the Adams Administration, (Philadelphia, Walker and Gills, 1846) 162 1 Written within the context of the Cold War and more specifically the rise of McCarthyism, both scholars acknowledged the impact of “modern parallels” on their work, and it is thus unsurprising that both authors viewed virtually every aspect of the acts passage and impact through the lenses of civil liberties.2 For example, although Miller’s work lacks both an overall thesis and analytical depth, he still manages to pointedly conclude that reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts underscores how “the issue, then and now, is the same,” that “without a doubt liberty of speech and of the press is at the heart of all liberty…in every society worthy to be called free there is an untrammeled play of public opinion; immunity from criticism is the privilege of no government officials; and the right of arguing about ideas is jealously guarded.”3 Echoing Miller’s preoccupation with modern concerns, James Morton Smith contested “it was not until the years 1798-1801, when the Sedition Act was debated and enforced, that liberty of speech and press became an issue which focused attention on the role of the First Amendment in a republican form of government.”4 Ergo, each author’s analysis left little room for grounding their narratives in the political culture of the 1790’s, and thus distorted both the passage and reaction to the Alien and Sedition Act from its proper context. Furthermore, because of the “modern parallels” acknowledged by each author, both authors make the Republicans the protagonists of their narrative.5 This inevitably makes their analysis of the Republicans tends toward hagiography. For example, Matthew Lyon, the Vermont Congressman who was first to be tried under the Sedition Act, is alternatively described as a “martyr to freedom of the press,” a “republican hero,” and a “political martyr.”6 Writing from his prison cell in Vermont, Lyon himself used similar terminology to describe his predicament.7 However, it should be noted that Miller and Smith’s desire to display the outrage the Alien and Sedition acts instigated (and by implication, 2 James Morton Smith, Freedom’s Fetters, The Alien and Sedition Acts and American Civil Liberties (Ithica, Cornell University Press, 1956) xviii 3 John C.Miller, Crisis in Freedom, The Alien and Sedition Acts, (Boston, Little, Brown and Co. 1951) 232. 4 Smith, Freedom’s Fetters, ix. 5 Smith, Freedom’s Fetters, xviii 6 Miller, Crisis in Freedom, 109, Smith Freedom’s Fetters 245. 7 Smith, Freedom’s Fetters, 237 2 perhaps instigate some of their own against McCarthy) produced one unusual side effect: it lead both to include an amount of popular reaction unusual for the top-down history that characterized much of the historical scholarship in the 1950’s. Yet this incidental benefit, because it stems from the author’s preoccupation with civil liberties, actually serves to deepen their distortion of the 1790’s political context. Thus, we see not only how the overarching context of McCarthyism influenced Miller and Smith’s depiction of reaction to the Alien and Sedition Act, but how that overarching context also helped lead to a hagiographical depiction of Republicans. The overriding concern with free speech and civil liberties established by Miller and Smith continued with Leonard W. Levy’s Emergence of a Free Press. Although Levy’s work did not appear until 1985, it was published as an expanded and revised version of Levy’s 1960’s work Legacy of Suppression: Freedom of Speech and Press in Early American History, and Levy’s overall focus on the legal implications of the Alien and Sedition Act remained unchanged. A legal historian, Levy was much more concerned then Miller and Smith with the legal nuances of the Alien and Sedition Acts, and believed that the overall importance of the reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts was that “it provoked American libertarians to formulate a broad definition of the meaning and scope of liberty of expression for the first time in our history.”8 Slightly removed from McCarthyism, but still operating under the overarching context of the Cold War, Levy’s narrative reads like an analysis of American triumphal march to legal egalitarianism, and one almost senses that Levy wanted to invite an implicit comparison with Communism. Additionally, although Levy has shifted the focus slightly from Miller and Smith, his preoccupation with the legal implications of the Alien and Sedition Acts leaves his narrative with the same lack of 1790’s political context. Levy also continues the hagiographical depiction of Republicans, albeit in a slightly less pronounced manner the Miller and Smith. For example, both weaknesses are evident when Levy discusses the reaction of 8 Leonard W. Levy, The Emergence of A Free Press (New York, Oxford University Press, 1985) 282. 3 what he terms the “American libertarians” to the Alien and Sedition Acts.9 It is clear from his narrative that when Levy uses the term, he is mainly referring to George Hay, a Republican colleague of Jefferson and Madison; and his pinnacle example of “libertarianism” is his work An Essay of Liberty of the Press. Respectfully Inscribed to Republican Printers Throughout the United States (1799). Levy argues the pamphlet advanced American legal theory by advocating an “absolutist” notion of free speech, but generally fails to provide any adequate contextual discussion of their immediate implications for American political culture.10 Hay was writing partially as a result of the political fallout from the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves, but Levy’s analysis eschews Hay the politician for Hay the erudite legal theorist. In this manner, Levy can also be seen as depicting Republicans uncritically. Ergo, we see how Levy’s top down history continues the trend of robbing the Alien and Sedition Acts of their proper political context by focusing exclusively on their legal implication while simultaneously leading to an uncritical portrait of Republicans. The first rebuttal to scholars who viewed the importance of the Alien and Sedition Acts in terms of various legal implications came in Donald Stewarts 1969 work The Opposition Press of The Federalist Period. Stewart overall argument that “the skillful use and presentation of propaganda” was the main reason for the Jeffersonian victory in 1800 recognized that “however crucial were the principles of democracy, they did not develop, nor continue to exist in a political vacuum.”11 Although Stewart’s work was a revised and greatly expanded version of his 1950 doctoral dissertation, Opposition Press of the Federalist Period shows some of the influence of the “bottom up” focus of social history by extensively chronicling the reactions of ordinary Americans (or at least literate white males) to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Stewart’s prodigious research however, was 9 Levy, Free Press, pg. 282 Levy uses Hay’s words to describe what he means by an absolutist concept of free speech: “ ‘A man may say every thing his passions suggest; he may employ all his time, and all his talents, if he is wicked enough to do so, in speaking against the government matters that are false scandalous and malicious’ without being subject to prosecution.” Levy, Free Press, pg. 313. 11 Donald Stewart, The Opposition Press of the Federalist Period (Albany, State University of New York Press, 1969) ix, 449. 10 4 offset by his works lack of analytical depth or explanation. Throughout his narrative, quotes are simply piled on top of one another and left to stand on their own without any analysis from the author. Additionally, though Stewart claims that he is not an “apologist” and that “there is also a Federalist version” of history, his uncritical depiction of Republicans bear a resemblance to the descriptions of party loyalists. Thus, although Stewart’s work is noteworthy for it’s attempt to restore the Alien and Sedition Acts to their proper context, this attempt falls short because of a lack of analytical depth, and his unabashedly Republican perspective continues the hagiography of that party begun by previous historians. More recently, historians have finally begun to build on Stewart’s work, endeavoring to analyze the Alien and Sedition act within the context of the developing political culture of the early Republic, but only hesitantly starting to treat Republicans critically. A major reason behind this shift is undoubtedly the historiographic turn towards cultural history. The emphasis on words and their underlying meaning as espoused by the linguistic turn has lead historians to examine the impact of the printed word American political culture, and subsequently reposition reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts within that larger framework. Furthermore, the lasting impact of social history has left historians attentive to those left on the periphery of the master narrative. Historians Jeffry Pasley, in his work Tyranny of the Printers, Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic, and Marcus Daniel, in his work Scandal and Civility, Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy, contest that previous historians “remarkably tenacious” emphasis on the various legal implications of the reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts is insufficient because their work “does not deal extensively with what the law aimed to, and failed, to control: the political behavior of the journalists.” 12 Both Pasley and Daniel thus place the popular reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts within the context of “the central role of newspapers in nineteenth century politics” with newspaper editors “rescued from 12 Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility, Journalism and the Birth of American Democracy, (New York, Oxford University Press, 2009) 371-372 n.7, and Jeffry Pasley, The Tyranny of the Printers, Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic, (Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press 2001), 128. 5 the condescension of their own time and posterity” and reintroduced as “the most pivotal and characteristic political figures of the era.”13 Each historian identifies the Alien and Sedition Act as “one of the pivotal moments in the partisan battle” because instead of silencing the Republican press, the backlash produced proved to be an incubator for Republican opposition, mainly through an explosion in the number of Republican editors.14 However, although Daniels concurs with Pasley in identifying the Alien and Sedition Acts as a critical turning point, he also argues that overall Pasley employs a “rather conventional and celebratory approach to the rise of Jeffersonian democracy.”15 Although Daniel’s stops short of calling Pasley’s work hagiographical, he points out that Pasley’s work is overwhelmingly told from the Republican point of view, noting that only one chapter is specifically devoted to Federalist editors. Thus, although Daniels is retreading much of the same ground as Pasley by endeavoring to restore the journalist to center of American political culture, he differs from Pasley by allotting Federalist and Republican editors nearly equal space in the narrative. Furthermore, Daniels also points out critical facts that he believes Pasley and other historians have papered over. For example, Daniels emphasizes how “Federalists policies of press regulation and immigration restriction were popular, reflecting a very modern intolerance for political dissent and an equally modern commitment to the ideas of ethnic and racial nationalism.”16 Thus we see how, through the combined efforts of Pasley and Daniels, historians have at least begun to restore the Alien and Sedition Acts to their proper political context and simultaneously begun to treat Republicans slightly more critically. 13 Pasley, Tyranny of the Printers, 13, and Daniel, Scandal and Civility, pg. 6. Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 277. 15 Marcus Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 289, n.10. 16 Daniel, Scandal and Civility, 277. 14 6