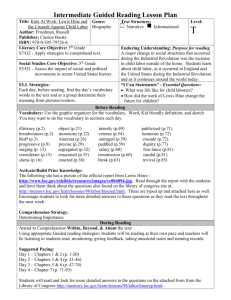

The Power of Man – Lewis Hine

advertisement

The turn of the century and the early 1900s were filled with various types of photography and photographical practices. The debate about whether photography was an art form was being fought, with Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz pushing full force. On the other hand, spearheaded by Jacob Riis, photography was also being used as a documentary tool, recording pitiable conditions among the poor and immigrant populations. After World War I, and during the Great Depression of the 1930s, photographers such as Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans worked with the government and the FSA to document how the country was dealing with its hard times. Lewis Wickes Hine stepped out of the box and didn’t fit into any specific photographic group. His artistically composed works portray the lives of the lower class, and many depict America during the depression, yet even still, Hine doesn’t limit himself to one category. Professor Peter Seixas states, “while [Hine’s] photographic themes and purposes maintained a considerable consistency over the course of his life, the uses to which his photographs were put changed dramatically.”1 Steelworker Standing on Beam, Touching the Tip of the Chrysler Building (1931), a photograph from Lewis Hine’s Empire State Building series substantiates Seixas’s statement, and shows how Hine’s work deviates from all other photographers at the time. Introduced to the medium of photography while working at the Ethical Culture School, Hine’s first subjects were immigrants entering the United States from Ellis Island. His images of the poor differed greatly from photographers such as Jacob Riis in that his images convey “that hardship was the result of neither Seixas, Peter. "From "Social" to "Interpretive" Photographer." American Quarterly. no. 3 (1987): 381. 1 incompetence nor lack of assiduity, and that poverty did not necessarily presuppose moral dubiousness.”2 He didn’t add any moral implications to the people and scenes he was photographing. Lewis Hine had two goals, and the images of the poor, immigrants, and child laborers brought his first aim to fruition: “I wanted to show the things that had to be corrected.” The biggest discrepancy between Lewis Hine and his contemporaries was his attitude towards the growing city and the relationship between man and machine. Stieglitz, Strand, Atget, and Abbot were all photographers working around the same time as Hine, but they focused more on infrastructure than on the man behind it. Paul Strand’s Wall Street (1916) minimizes the city dweller or worker by placing him in front of an ominous and overpowering architectural backdrop. Stieglitz, Atget, and Abbot remove man altogether, simply showing what may be left over when man is gone. Lewis Hine’s Empire State Building series is a complete turn around from the styles of the above-mentioned artists. Man is the prime subject of each and every photograph, and instead of cowering away from tall buildings and strong infrastructure he towers over it. Hine’s second goal was “to show the things that had to be appreciated.” After World War I, he “first perceived expressions of honor, strength, and courage”2 in the faces of Europeans. This later inspired him to search for the same countenance in the workers in America. Steelworker Standing on Beam, Touching the Tip of the Chrysler Building encompasses both of Lewis Hine’s goals in one perfectly composed photograph. Two thick cables, running diagonally from the bottom to the top of the composition, Freddy Langer, The Empire State Building, (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 1998), chap. Introduction. 2 frame the main subject matter of the piece: a worker and the distant Chrysler Building. The man stands precariously on a steel beam, one foot barely giving him any support. The casual stance at such a height gives the illusion of lightness and airiness. The worker’s left arm is outstretched, with seemingly no effort and no fear, ending with his index finger gently touching the tip of the Chrysler Building’s spire. By placing the man on such a high level, Hine is able to convey that the “worker is not a lower form of life.”2 The composition in itself depicts Hine’s second goal: to show the things that had to be appreciated. The man is the object in the photograph that is in most focus while the building is in the background under a foggy haze. Unlike other photographers, Lewis Hine is obviously not concerned with the architecture and beauty of the building, but the hardworking individual who built it. The worker’s pose is also reminiscent of Renaissance painting, specifically Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam (1508-1510). In Hine’s composition, it is the worker’s finger that is outstretched in the same fashion that God reaches towards Adam in the ceiling fresco. Jonathan L. Doherty describes the moment perfectly when he says, “Hine showed the relationship between the men and their machines – that it is the men who are controlling the machines... They are not dwarfed by the construction of a giant turbine or a railroad car or a great skyscraper, for they are the ones who have built them.”3 This greatly contrasts with Paul Strand’s Wall Street mentioned earlier. Jonathan L. Doherty, Men At Work, (Rochester, New York: Dover Publications, Inc and International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, 1977), chap. Introduction. 3 Many of Hine’s Empire State Building photographs show heroic images of man conquering the laws of nature – mainly gravity. This image stands out from the rest and shows the other side of the coin as well – the strain on the worker. It is here that Lewis Hine succeeds in his first goal: to show the things that had to be corrected. Unlike images entitled Skyboy and A Connector on the Move, the worker in this particular image doesn’t carry a strong posture required of a superhero. His upper body slightly slouches, his eyebrows are brooding, and there is no sign of a smile on his face. If anything, the image emphasizes a long and sad countenance. His downturned head brings his pupils to the top of his eye sockets, emphasizing the tired nature of the worker. This contrasts greatly with the other work by Hine in this series, as many of the other workers stare stoically up and beyond. This particular series was constructed and compiled over a six-month period from 1930 to 1931.2 At the completion of the series, he wrote to his mentor Florence Kellog stating that “even skyscrapers have their basements and skyscraping has its rebounds and depressions.” Though Freddy Langer writes that Lewis Hine still held a positive attitude about man and machine up until 1933, this excerpt from a personal letter shows that Hine still saw the downside to industrialization and mechanization, and saw the necessity of reform. With Steelworker Standing on Beam, Touching the Tip of the Chrysler Building perhaps Lewis Hine was trying to convey this darker emotion that he was feeling. He continued to follow this train of thought. While earlier Hine would proclaim that “cities do not build themselves, machines cannot make machines, unless at the back of them all are the brains and toil of men… [And that] the more machines we use the more do we need real men to make and direct them,” working for the FSA and the government after completing his Empire State Building works, confirmed to him that “the human being seemed to have become a slave to the machine.”2 The worker depicted in the featured image of this essay, though positioned as a god, holds a darker message and look in his eyes. Agreeing with Seixas’s statement, used in the form of advertising for the building, Lewis Hine deviated from his usual social reform audience. Though the audience may have shifted, Hine’s work doesn’t lack the same meaning and purpose that it always has. The goals of his earlier works are still prevalent in Steelworker Standing on Beam, Touching the Tip of the Chrysler Building. In this one photograph, Hine is able to combine artistic composition, social reform messages, documentary style, and architectural awe, superseding the simple photographic categories placed before him. The Power and Vulnerability of Man: Lewis Hine and Workers of the Empire State Building Marina Nebro Art History 258: History of Photography Professor Suchma