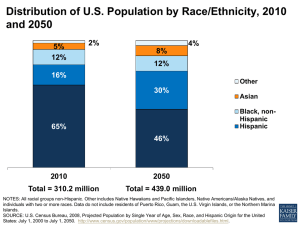

AP Human Geography Unit III: Cultural Patterns and Processes

advertisement