Sources, Normative Hierarchies and Legal Reasoning Giorgio Pino

advertisement

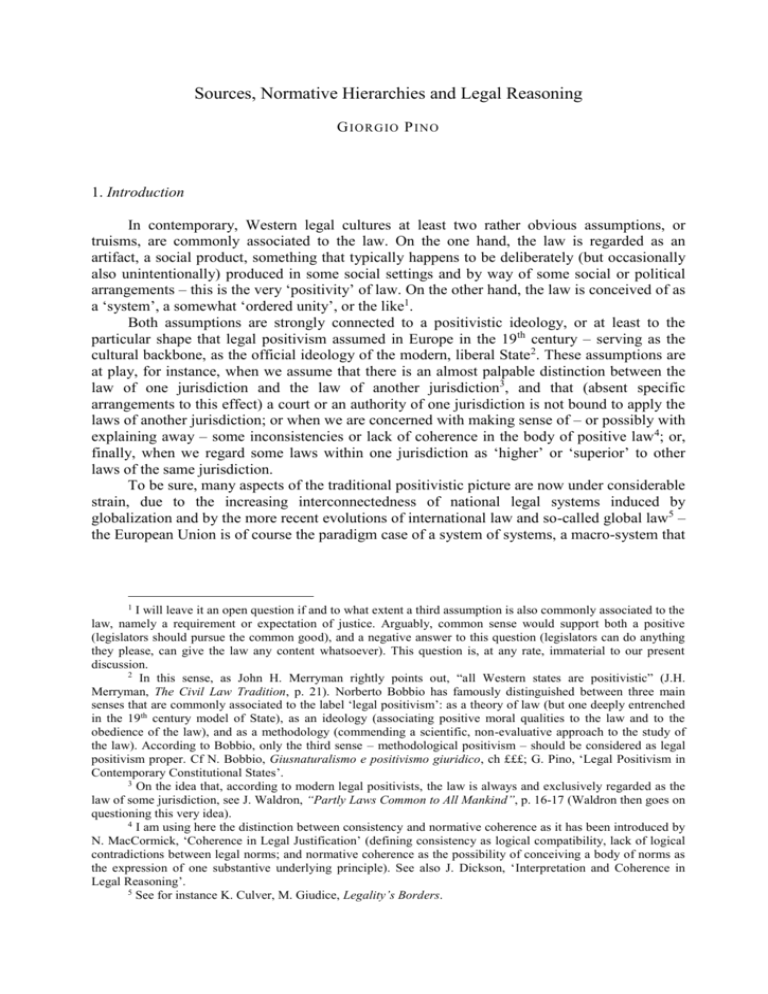

Sources, Normative Hierarchies and Legal Reasoning G IOR G IO P INO 1. Introduction In contemporary, Western legal cultures at least two rather obvious assumptions, or truisms, are commonly associated to the law. On the one hand, the law is regarded as an artifact, a social product, something that typically happens to be deliberately (but occasionally also unintentionally) produced in some social settings and by way of some social or political arrangements – this is the very ‘positivity’ of law. On the other hand, the law is conceived of as a ‘system’, a somewhat ‘ordered unity’, or the like1. Both assumptions are strongly connected to a positivistic ideology, or at least to the particular shape that legal positivism assumed in Europe in the 19th century – serving as the cultural backbone, as the official ideology of the modern, liberal State2. These assumptions are at play, for instance, when we assume that there is an almost palpable distinction between the law of one jurisdiction and the law of another jurisdiction3, and that (absent specific arrangements to this effect) a court or an authority of one jurisdiction is not bound to apply the laws of another jurisdiction; or when we are concerned with making sense of – or possibly with explaining away – some inconsistencies or lack of coherence in the body of positive law 4; or, finally, when we regard some laws within one jurisdiction as ‘higher’ or ‘superior’ to other laws of the same jurisdiction. To be sure, many aspects of the traditional positivistic picture are now under considerable strain, due to the increasing interconnectedness of national legal systems induced by globalization and by the more recent evolutions of international law and so-called global law5 – the European Union is of course the paradigm case of a system of systems, a macro-system that 1 I will leave it an open question if and to what extent a third assumption is also commonly associated to the law, namely a requirement or expectation of justice. Arguably, common sense would support both a positive (legislators should pursue the common good), and a negative answer to this question (legislators can do anything they please, can give the law any content whatsoever). This question is, at any rate, immaterial to our present discussion. 2 In this sense, as John H. Merryman rightly points out, “all Western states are positivistic” (J.H. Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition, p. 21). Norberto Bobbio has famously distinguished between three main senses that are commonly associated to the label ‘legal positivism’: as a theory of law (but one deeply entrenched in the 19th century model of State), as an ideology (associating positive moral qualities to the law and to the obedience of the law), and as a methodology (commending a scientific, non-evaluative approach to the study of the law). According to Bobbio, only the third sense – methodological positivism – should be considered as legal positivism proper. Cf N. Bobbio, Giusnaturalismo e positivismo giuridico, ch £££; G. Pino, ‘Legal Positivism in Contemporary Constitutional States’. 3 On the idea that, according to modern legal positivists, the law is always and exclusively regarded as the law of some jurisdiction, see J. Waldron, “Partly Laws Common to All Mankind”, p. 16-17 (Waldron then goes on questioning this very idea). 4 I am using here the distinction between consistency and normative coherence as it has been introduced by N. MacCormick, ‘Coherence in Legal Justification’ (defining consistency as logical compatibility, lack of logical contradictions between legal norms; and normative coherence as the possibility of conceiving a body of norms as the expression of one substantive underlying principle). See also J. Dickson, ‘Interpretation and Coherence in Legal Reasoning’. 5 See for instance K. Culver, M. Giudice, Legality’s Borders. cuts across the many individual systems it comprises6. Still, more than a grain of truth remains with the two basic assumptions above – that the law is deliberately produced by some social arrangement, and that the law is supposed to present itself in accordance to some ordering criteria. This is where the theory of legal sources steps in. As commonly understood, the positivity assumption requires that any law must be traceable back to a ‘source’; and the systematicity assumption requires that the sources of law must be ordered somehow, they must form a kind of hierarchy. Accordingly, a sort of ‘standard picture’ of adjudication emerges: adjudication, and legal interpretation generally, takes place within a framework of previously established legal sources, they actually presuppose some (hierarchically ordered) set of legal sources whose existence and hierarchical ordering is entirely independent from legal interpretation itself – it is established by the Constitution, or by political authorities, and by the very structure of the State7. Legal sources both bind and guide the interpreter in discharging her adjudicative role, that is, in the charge of applying the law as it is announced in general terms by the relevant legal sources. (Sometimes, the picture is even supplemented by some authoritative, legally mandated criteria of legal interpretation: thus, the interpreter is not only confronted with a closed and hierarchically ordered list of legal materials, but also with supposedly binding criteria to interpret them8.) According to the standard picture, then, legal sources and their hierarchy are a sort of objective element of legal reasoning, a datum that imposes itself on the interpreter. Interpretation works on previously and independently established legal sources9. Given this general background, the aim of this paper is two-fold. On the one hand (sec. 3), I will engage in some theoretical analysis of the concept of normative hierarchy, and to this regard I will try to show that in the law we should expect to find not just one concept of normative hierarchy at work, but many. Differently put, the concept of normative hierarchy is ambiguous, it can be used to describe different kinds of relations between legal norms, relations that can produce different effects, and so it is important to make it clear what concept of hierarchy is relevant in which context. (For instance, what is the actual concept of normative hierarchy at play when we say that some constitutional norms are ‘superior’ to other constitutional norms?) Before going to that, however, it will be useful to introduce some basic concepts and distinctions that, despite their importance, are sometimes overlooked in contemporary jurisprudential discussions (sec. 2): these concepts, it will emerge, will play a key role in our effort to provide a more nuanced and precise account of normative hierarchies in the law. On the other hand (sec. 4), I will try to underscore the role of legal interpretation and argumentation in both the working and the establishment of normative hierarchies in the law. See J. Dickson, ‘How Many Legal Systems? Some Puzzles Regarding the Identity Conditions of, and Relations between, Legal Systems in the European Union’, and ‘Towards a Theory of European Union Legal Systems’. 7 See for instance H. Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition, pp. 25-26 (the traditional theory of sources of law represents “the basic truth”, “it is a part of his [scil., the average Continental lawyer’s] ideology”); T. Spaak, ‘Legal Positivism and the Objectivity of Law’. 8 This is the case, for instance, with the Italian legal system, which provides both a list of sources (apparently ordered according to an order of priority), and a few criteria for their interpretation (literal meaning and intention of legislator); see artt. 1 and 12 of the so-called ‘Preleggi’ (general provisions on law, inserted at the beginning of the Civil Code) respectively. See J.H. Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition, p. ; 9 The standard picture is obviously disavowed by legal realists (as well as by other anti-formalistic movements, such as the Critical Legal Studies), according to whom there are no such things as binding sources of law, let alone a binding and definite hierarchy of sources of law. In the legal realist picture of adjudication, legal reasoning is influenced by all kind of factors (policy arguments, cultural factors, individual sense of justice), and the hierarchy of legal sources may act only as an ideological a posteriori rationalization, a window-dressing in fact, of the judicial decision. See A. Ross, ‘Review of H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law’, and On Law and Justice, £££. LEITER??? 6 My working hypothesis here is that legal interpretation, and the one performed by courts in the first place, is the place where normative hierarchies are in fact established. Sometimes, indeed, and contrary to the standard picture of the relation between sources and interpretation hinted at above, interpretation precedes, and may even establish, legal sources themselves, rather than the other way round. I will then conclude with some general remarks on the scope of freedom and constraint in legal argumentation (sec. 5). Unfashionably, in this paper I will be mainly concerned with the viewpoint of national, municipal legal systems, and of the legal actors operating therein. Accordingly, I will not deal with the issue of the legal sources and their hierarchies in international law, or with the sources associated to the emerging body of global law and global constitutionalism. This limitation in the scope of my analysis is not meant to convey the impression that the question of the hierarchy of sources in international law is not practically important or not worth theoretical investigation – far from it10. In fact, the reason for the limitation of the scope of my analysis is that by situating my argument to the context of national legal systems I intend to make my point – that legal sources and their hierarchies entertain a bidirectional relation with legal interpretation – more visible and striking. On the contrary, in non-state institutional contexts it is indeed almost obvious that interpreters enjoy a wide margin of appreciation in determining the respective strength and hierarchical position of the various legal sources11. 2. Some preliminary definitions and distinctions Generally speaking, the topic of legal sources as such is normally neglected in contemporary legal theory12. This is unfortunate since, as we have seen in sec. 1 above, the topic of the sources of law is intrinsically related to the positivity requirement of the law, which is central to our common understanding of the law, and even crucial for a positivist theory of law – the whole point of legal positivism being that of conceiving of the law just as ‘positive law’. Indeed, it is essential to any positivist understanding of the law a) that the law is conceptually distinct and distinguishable from other normative phenomena – from morality in the first place; and b) that the law has boundaries, it has a ‘limited domain’13. It is easy to see how these two positivistic requirements are related to the ‘positivity assumption’ introduced above (sec. 1), and in turn to the topic of the sources of law. While morality is not deliberately 10 Recent work on this topic, with remarkable jurisprudential implications, include M. Koskenniemi, ‘Hierarchy in International Law: A Sketch’; J.J.H. Weiler, A. Paulus, ‘The Structure of Change in International Law or Is There a Hierarchy of Norms in International Law?’; S. Besson, ‘Theorizing the Sources of International Law’. 11 See A.M. Slaughter, A Global Community of Courts; S. Cassese, I tribunali di Babele; J. Allard, A. Garapon, Les juges dans la mondialisation. The alleged absence of a rule of recognition (i.e. the rule that lists and orders the criteria of validity and so the very sources of the law) in international law is what prompted H.L.A. Hart to regarding international law as a borderline case of law. See H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, ch X; J. Waldron, ‘International Law: “A Relatively Small and Unimportant” Part of Jurisprudence?’. 12 Notable exceptions include: A. Peczenik, On Law and Reason; R. Guastini, ‘Fragments of a Theory of Legal Sources’; J. Gardner, ‘Some Types of Law’; R. Shiner, £££. The concept of source plays a crucial role in the version of legal positivism elaborated by Joseph Raz (the ‘sources thesis’), but it should be noted that Raz’s notion of a legal source is rather technical and admittedly different from the one prevalent in the common usage of lawyers; see J. Raz, ‘Legal Positivism and the Sources of Law’, pp. 47-48, and ‘Legal Reasons, Sources and Gaps’, p. 63. On the other hand, some very interesting research on the topic of legal sources is currently done by some international lawyers and comparative lawyers. 13 J. Raz, ‘Legal Principles and the Limits of Law’; F. Schauer, ‘The Limited Domain of Law’; L. Alexander, F. Schauer, ‘Law’s Limited Domain Confronts Morality’s Universal Empire’; F. Schauer, V. Wise, ‘Legal Positivism as Legal Information’. created in social settings, law is typically created therein; and if the law is the product of socially contingent acts of law-making, then the law of a jurisdiction is coextensive with the sum total of the recognized acts of law-making – i.e., the law of a jurisdiction is what is identifiable through the sources of the law that are in place in that jurisdiction. H.L.A. Hart’s doctrine of the rule of recognition (a social rule that lists the finite set of criteria of validity – the sources of law – in place within a certain social setting) compounds nicely all these positivistic theoretical requirements14. Once it has been duly recognized the central place of the concept of legal sources for any understanding of the law, and with particular magnitude for a positivistic theory of law, a survey of some useful theoretical concepts is in order, to be in a better position to understand what a source is, and how it works. The four following subsections will briefly introduce some important definitions and distinctions to this effect. 2.1. Legal Acts, Legal Texts, Legal Norms The first distinction to be drawn is between acts, texts and norms. By a legal act I mean the procedure that has to be followed by a duly empowered body or institution in order to achieve the result of changing the law, by way of creation of new law, or derogation, modification, or abrogation of existing law – in short, the law-making process. In contemporary legal systems, the law-making process is normally and heavily regulated by the law itself: by (secondary) rules of change, or norms of competence15. The legal regulation of the law-making process usually includes: the identification of a body, or more accurately of a set of bodies that are empowered to take that part in the law-making process (i.e., to exercise law-making power), and their respective roles therein; the procedures to be followed in order to properly achieve the result of creating new law, or of derogating, modifying, or abrogating existing law; sometimes, the material limits to the proper exercise of the law-making power. By legal text, or legal document, I mean the normal outcome of a law-making process – in contemporary legal systems, the law-making process typically results in an official legal document16. By legal norm I mean the content of meaning that is normally expressed by a legal text – or more accurately, by specific portions of it17. Legal interpretation, or textual interpretation, is the process of ascertaining the meaning of a legal text. Accordingly, legal norms are identified by way of legal interpretation. As we have seen (sec. 1 above), the process of legal 14 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, ch . For recent critical discussion on the concept of rule of recognition, see the various essays in M. Adler, K. Himma (eds.), The Rule of Recognition and the U.S. Constitution; G. Pino, ‘Farewell to the Rule of Recognition?’ 15 On rules of change, see H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, ch £££; on norms of competence, see T. Spaak, The Concept of Legal Competence, and ‘Explicating the Concept of Legal Competence’; on the idea that the law regulates its own creation, H. Kelsen, General Theory of Law and State, £££. Norms of competence are sometimes included in the general class of ‘meta-norms’. Still, as should appear clear from the discussion in this subsection, defining norms of competence as meta-norms is mistaken, since norms of competence do not refer to norms proper, but to legal acts. 16 The obvious exception here is custom, whose production does not necessarily – and not even typically – result in a formal document. The role of custom as a source of law in contemporary legal systems is notoriously a marginal one. 17 The distinction between legal texts and their meanings (the norms they convey) is reminiscent of von Wright’s distinction between a norm and a norm-formulation (see G.H. von Wright, Norm and Action, pp. 93-95); this distinction is not always duly acknowledged in contemporary analytical legal theory. For some notable exceptions, see R. Guastini, ‘Rule-Scepticism Restated’, p. 147; D. Priel, ‘Trouble For Legal Positivism?’; see also F. Schauer, Playing by the Rules, pp. 62-64 (acknowledging that the distinction between the rule and the ruleformulation is important, but adding that “the implications of that lesson are limited, and likely to be exaggerated”, at 64). interpretation is sometimes regulated by the law itself; but normally the various methods or ‘canons’ of legal interpretation, and their respective order of priority, are in actual fact the product of the relevant legal culture. In the definition of legal norm provided at the beginning of this paragraph, I have said that a legal norm is ‘normally’ expressed by a legal text. By this I mean that legal norms may be established also by way of an argument that does not have the form of textual interpretation – one that does not present itself has the ascription of meaning to a legal text. This is the case of legal norms established by analogical reasoning, and of some legal unstated legal principles18. In such cases we may use the label ‘unstated norms’, to mark the difference with (and the different role played by the interpreter in the case of) the other, textually stated legal norms. Now, with this distinctions in mind, we can see that sometimes the concept of ‘source’ is referred to the law-making act, and sometimes it is referred to the documents that are typically created by way of those law-making acts. This ambiguity is rather innocuous. Nonetheless, and unless stated otherwise, in the following of this paper I will use ‘source’ only in the second sense, as a document duly produced as the result of a law-making process, and typically subject to legal interpretation in order to ascertain its meaning (i.e., the norms it expresses). 2.2. Type-Sources and Token-Sources Legal sources present themselves, typically, in the form of documents enacted as the outcome of a certain – legally regulated – procedure. Now, to this regard it is possible to further distinguish between a kind of legal source (a type-source), and a specific instance of a legal source (a token-source). Accordingly, it is possible to talk of legislation as a source of law (in the ‘type’ sense of source), as well as of a single statute as a source of law (now in the ‘token’ sense of source). Much on the same footing, it makes perfect sense to say that while legislation is a source of law (in the ‘type’ sense of source) in a certain jurisdiction J, a specific statute is disallowed to serve as a source of law (in the ‘token’ sense of source), due to some fatal defects in the procedure of enactment, or to the fact that it has been repealed by subsequent legislation. 2.3. Formal Validity, Material Validity, Existence As we have already seen (sec. 1 above), legal sources are what determines the distinction between law and non-law – something can count as law only if it is traceable back to a legal source. And in jurisprudential jargon there is a specific, magic word that is used to refer to what belongs to law (to a legal system) – validity. So it would seem natural indeed to relate directly legal sources (the basis of legality) to legal validity (the property of being legally existent). Things are somewhat more complicated than this, though. For one thing, contemporary legal systems usually resort to both ‘formal’ and ‘material’ criteria of legal validity (borrowing from Kelsen’s terminology, legal systems usually combine both ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ criteria of legal validity19). Accordingly, we should conveniently distinguish between a formal and a material dimension of legal validity. 18 See N. MacCormick, Legal Reasoning and Legal Theory, £££. The idea that legal principles lack ‘pedigree’ – i.e., are not formally enacted – is stressed by R. Dworkin, ‘The Model of Rules I’; but Dworkin patently overstates the case here, since of course there may be – and there often are – legal principles expressly formulated in legal documents. 19 For the static/dynamic distinction, see H. Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law, £££, and General Theory of Law and State, £££. Formal validity obtains when a legal act is enacted in accordance to all the procedural requirements that surround that specific kind of law-making activity; when this is the case, then the relevant legal act, and the legal document produced thereby, are formally valid. Material validity obtains when a legal norm is compatible (i.e., it lacks logical contradictions to and is substantially coherent, in the sense introduce above, fn 4) with another, ‘superior’ norm20. Accordingly, material validity is not source-based, but content-based. Its ascertainment requires the comparison of its content with the content of another norm. As a consequence of the definitions above, formal validity is a quality of legal sources, whereas material validity is a quality of norms. (Since formal validity and material validity are distinct properties, it is possible to introduce even a third concept, such as ‘full validity’, that would obtain when a legal norm is both materially valid and is expressed by a legal source that is formally valid21.) The importance of separating the two faces of legal validity lies not only in the fact that they are different from a conceptual point of view (one pertains to procedures, the other to meanings), but also in some aspects of legal practice. For instance, in jurisdictions where a judicial review of legislation is in place, it can happen that a statute is challenged either on formal or on material grounds; or it can happen that a constitutional challenge targets only a single allegedly materially invalid norm, among the many alternative norms that can be derived by means of interpretation by a single statute. Moreover, if we recall the possibility (hinted at above, sec. 2.1) that some legal norms cannot be considered as the meaning of a legal text, such as in the case of analogy and of some legal principles, then we have legal norms that are not evaluable in terms of the formal validity of their sources. Moreover, formal and material validity do not seem to exhaust all the possible ways in which a source or a norm can have effect in a legal system 22. Indeed, it can happen that a legal source or a legal norm is actually used by the legal actors of a legal system despite the fact that that source is formally invalid, or the fact that that norm is materially invalid. This can happen in two ways. On the one hand, it can happen that a legal source or legal norm is actually invalid, but some actors of the system do not have the power to declare its invalidity; or it can happen that its invalidity has been mistakenly ignored by the competent legal actor. In such cases, there can be an obligation on some legal actors to give effect to a legal source or norm that is actually invalid. On the other hand, it can be the case that a legal source is formally invalid, but legal actors decide that the relevant fault is indeed irrelevant, a minor one, and so they decide to treat that source as actually formally valid. So there seem to be cases in which an invalid source or norm is actually treated as valid: the fact that the procedure for the production of a legal document (formal validity) has not been perfectly complied with, or that the content of the legal norms derived by a source is not perfectly compatible with a higher norm, do not necessarily prevent legal actors from using and giving legal effect to the formally invalid source or to the materially invalid norm. In order to describe such cases, we cannot resort to the concept of validity: we need a different concept – ‘existence’23. From the point of view of legal theory, two interesting lessons can be drawn from what has been said in this subsection. I qualify ‘superior’ with inverted commas here, because I want to stress that as far as this definition is concerned we do not still have any criterion whatsoever in order to ascertain the ‘superiority’ of one norm over another. This point will be specifically taken up at sec. 3.2 below. 21 R. Guastini, ‘Invalidity’, p. 224; Wil Waluchow uses a similar concept, ‘systemic validity’, to refer to ‘full validity’ plus the fact that the fully valid norm is accepted and treated by the relevant legal actors as a valid norms: W. Waluchow, ‘Four Concepts of Validity’, p. 140 (Waluchow’s notion of ‘systemic validity’ is in turn borrowed and adapted from J. Raz, ‘Legal Validity’). 22 I am here ignoring the case of foreign norms whose operation in a legal system may be required by those system’s private international law provisions. This case is immaterial to my present concerns. 23 R. Guastini, ‘Invalidity’, p. 224; W. Waluchow, ‘Four Concepts of Validity’, p. 140. 20 First, both formal and material validity are a matter of interpretation, and as such they can be a matter of substantial disagreement between lawyers; likewise, treating an invalid item as nonetheless ‘existent’ is entirely an interpreter’s decision (on both points we will return shortly, see sec. 4 below). Second, any legal system is populated by various legal norms that somehow ‘belong’ to that system without being valid according to the criteria of validity of that legal system; this is so because legal actors will routinely use (treat as valid) certain laws that are not really valid, and because some norms of the legal system are not validated by other, ‘superior’ norms of that legal system, and so they are neither valid nor invalid – typically, this is the status of constitutional norms24. Accordingly, it is not true (actually, it cannot be true) that the legal system is the sum total of all the laws that are valid according to the criteria set by that legal system. 2.4. Institutionalized and Non-Institutionalized Sources; Binding and Permissive Sources I have defined a ‘source’ as, typically, a document duly produced as the result of a lawmaking process (see sec. 2.1 above). This, in fact, can be considered as the definition of an ‘institutionalized source’, i.e. a source whose production is regulated, with variable degrees of intensity, by other norms of the legal system. But ‘source of law’ is sometimes used in a different, more loose way, to refer to all the possible factors that determine or influence the decision of a legal actor – typically a judge. These factors could be any number of things: sense of justice, equity, cultural and political orientation, policy arguments, judicial precedents (in civil law countries), legislative intentions and preparatory materials, foreign legal materials, and so on. We can call all these ‘non-institutionalized sources’25. The distinction between ‘institutionalized’ and ‘non-institutionalized’ sources is ‘structural’ in character: it pertains to what a certain source is, and how it is produced (an aspect on which I will have more to say shortly, sec. 3 below). And this structural distinction should not be confused with a distinction pertaining a ‘functional’ aspect – what certain sources do, or can typically be expected to do. With reference to this aspect, the function of legal sources is to guide and determine decisions that are to be assumed by legal actors (legal actors are supposed to act on reasons provided by legal sources, with exclusion of those other reasons that have been excluded or not allowed by legal sources). More precisely, sources of law are expected to determine a legal decision (i.e., a judge is bound to apply a certain statute, as a legal source, even if she does not agree with the content of the source) – once they have been duly interpreted of course. So, a legal source is expected to provide legal actors with a place where to look for the legal norms that will then ground a legal decision26. Now, as far as the functional dimension of legal sources is concerned, it is possible to distinguish between ‘binding’ sources and ‘permissive’ sources27. Binding sources are those sources that the legal actor is bound to apply – if a legal actor disregards a binding source, his decision will be legally wrong (the decision will be invalid; or it will be considered as a reason to impose some kind of fine or liability on that legal actor; and so on). Permissive sources, on R. Guastini, ‘On Legal Order: Some Criticism of the Received View’. See A. Ross, On Law and Justice, pp. 75-78 (‘completely objectivated’, partially objectivated’, ‘nonobjectivated’ sources); A. Peczenik, On Law and Reason, p. 257 (‘substantive reasons’ v. ‘authority reasons’); R. Shiner, Legal Institutions and the Sources of Law, p. 3; R. Guastini, ‘On the Theory of Legal Sources. A Continental Point of View’, p. 305 (but note that Shiner and Guastini do not define the relevant distinction in exactly the same way). 26 See supra, fn 9 and accompanying text. 27 Various ways to present this distinction are provided by H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 294; A. Peczenick, On Law and Reason, pp. 261-264; L. Green, ‘Law and the causes of Judicial Decisions’, § 3. 24 25 the other hand, have lesser, and variable, weight: they can be disregarded without affecting the validity of the relevant legal decision (or without producing otherwise adverse consequences for the legal actor in question); their use is permitted, and it can improve the degree of persuasiveness, acceptability to the relevant legal decision. I will return to the distinction between binding and permissive sources shortly (sec. 4 above). What I mean to stress here is that the ‘institutionalized’/‘non-institutionalized’ distinction and the ‘binding’/’permissive’ one are not symmetric. A certain institutionalized source may be (perceived as) merely permissive, and a non-institutionalized legal source may (be perceived as) binding by the relevant legal actors. 3. Normative Hierarchies in the Law As noted at the beginning of sec. 3, the general interest to the topic in contemporary jurisprudential discussion has been rather scarce; and, as a matter of fact, the interest in a theoretical analysis of normative hierarchies in the law has been even more meager28. Sociologically, this may probably be related to the conjunction of two circumstances: the fact that the since the last few decades the agenda of contemporary debates in legal theory is mainly dictated by the Anglo-Saxon academe, and the fact that – due exceptions allowed – in the common perception of the average Anglo-Saxon legal scholar the hierarchy of legal sources does not really seem to be an issue worth exploring (this, in turn, is probably due to some perceived lack of ‘verticality’ in the structure of common law legal systems, as opposed to the pyramidal structure of civil law systems29). Be that as it may, I believe that there is some important theoretical work to be done on the concept of normative hierarchy, and that this work may produce useful tools for both civil and common law countries. And, at any rate, it is now almost a commonplace to note the ever increasing convergence between the civil law and common law traditions. I will begin with a brief exploration of the ways in which the concept of normative hierarchy appears – albeit not always under this label – in some landmark work in contemporary legal philosophy (sec. 3.1). Then I will try to elaborate and defend a possible taxonomy of different senses of normative hierarchy that are relevant to the law (sec. 3.2). 3.1. Normative Hierarchies in Legal Theory The topic of normative hierarchies appears prominently in Hans Kelsen’s legal theory. According to Kelsen, the legal system is characteristically structured in a hierarchical fashion (Stufenbau)30. This is so, because each valid norm of the legal system, N1, derives its validity from another (valid) norm N2, which prescribes the mode of production of N1. By mode of production, Kelsen basically means the forms and procedures to be adopted by the competent body in order to validly enact N1; to some extent, N2 may also predetermine the content of N1. Apart from the few ‘classics’ that I will present shortly, some recent investigations in the topic of normative hierarchies have been provided by R. Guastini, M. Troper, O. Pfersmann, G. Pino, J. Ferrer, J. Rodriguez. 29 In a recent book devoted to the theory of legal sources, written by a Canadian scholar but intended for an international audience, the topic of normative hierarchies is hardly noticed: see R. Shiner, Legal Institutions and the Sources of Law. Significantly, this absence has been immediately recorded by two European Continental reviewers of that book: J. Wolenski, R. Guastini, ‘On the Theory of Legal Sources. A Continental Point of View’. See also J.H. Merryman, The Civil Law Tradition, p. 26 (stating that in common law countries “there is no systematic, hierarchical theory of sources of law”). 30 H. Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law, ch V; General Theory of Law and State. 28 Accordingly, “the relation between the norm that regulates the creation of another norm and the norm created in conformity with the former can be metaphorically presented as a relation of super- and subordination. The norm which regulates the creation of another norm is the higher, the norm created in conformity with the former is the lower one”31. H.L.A. Hart has deployed some conceptual tools that make room for two, or maybe three, different kinds of normative hierarchies in modern, municipal legal systems. On the one hand, there is the fact that such legal systems comprise two kinds of rules, primary rules and secondary rules; primary rules are rules of obligation, secondary rules are rules that regulate the creation and modification (rules of change), individuation (rule of recognition), and application (rule of adjudication) of the primary rules. Accordingly, between secondary rules and primary rules a certain kind of relation is in place, and this relation can be usefully defined as a certain kind of normative hierarchy: primary rules are the object of secondary rules; secondary rules are meta-norms that refer to primary rules32. On the other hand, Hart associates the topic of sources and legal validity to the concept of the rule of recognition, and states that a rule of recognition can provide either a) an order of priority between the various sources it refers to33, or b) a principle of derivation of validity, such that one rule derives its validity from another rule, in hierarchical order34. Hart describes these last two hypotheses as cases of “a complex rule of recognition with [a] hierarchical ordering of distinct criteria”35. But indeed here we seem to have two separate instances of hierarchical ordering of norms or of sources, as Hart himself is ready do admit: a relation of derivation, and a relation of subordination36. 3.2. Towards a Taxonomy of Normative Hierarchies in the Law It is high time to propose a more-fine grained account of normative hierarchies in the law, one that takes into account the several important legal concepts and distinctions that we have introduced in precedent sections (legal sources, norms, formal validity, material validity). Following the lead of some recent work on the concept of normative hierarchy in the law37, I will propose a distinction between several relevant senses in which a hierarchical relation may obtain in the law. (I will deal mainly with hierarchies of sources and hierarchies of norms; I will leave out of direct consideration here the topic of hierarchies of organs and institutions.) H. Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law, p. 221. Hence, Kelsen adds, “the legal order is […] a hierarchy of different levels of legal norms”. Kelsen is here indebted to Adolf Merkl’s ‘gradualistic’ approach to law. But note that Merkl’s approach to normative hierarchies was more nuanced than Kelsen’s, comprising both the kind of hierarchies envisaged also by Kelsen, and hierarchies related to ‘legal strength’ – if a norm N1 can derogate to a norm N2, then N1 is hierarchically superior to N2 (see A. Merkl, ‘Prolegomena einer Theorie des rechtlichen Stufenbaues’). 32 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, £££. For a critical appraisal of this point, see D. Gerber, ‘Levels of Rules and Hart’s Concept of Law’. 33 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 101. 34 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 107: “if the question is raised whether some suggested rule is legally valid, we must, in order to answer the question, use a criterion of validity provided by some other rule”. 35 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 101. On the hierarchical structure of the criteria of validity enlisted in the rule of recognition, see M. Kramer, Where Law and Morality Meet, £££. Other Hartian scholars prefer to talk of different, hierarchically ordered rules of recognition: see J. Raz, ‘Legal Validity’, pp. 150-151; F. Schauer, £££. 36 H.L.A. Hart, The Concept of Law, p. 101. In much the same vein, see also R. Shiner, Legal Institutions and the Sources of Law, p. 38 (subordination ‘by derivation’, and subordination ‘by power of abrogation’). 37 Most notably the work of R. Guastini, ‘Fragments of a Theory of Legal Sources’, and ‘On Legal Order: Some Criticism of the Received View’. My account is not entirely identical to the one provided by Guastini, though. 31 A structural, or formal, hierarchy obtains when a norm, or more likely a set of norm, N1, regulates the production of a certain source (i.e., of a type-source). As a consequence, in order to count as a valid source, a given token-source S1 must have been enacted in conformity to the formal and procedural requirements set forth by norm N1. Clearly enough, this concept of normative hierarchy is directly related to the concept of formal validity (see sec. 2.3 above). A norm N1 is structurally or formally superior to a source S1, if it regulates the production of S1, or in other words if it is condition for the formal validity of S138. Differently put, a structural hierarchy obtains between a norm of competence (power-conferring norms, rules of change), and the legal sources that are produced as the effect of the correct exercise of that legal competence of power39. A material hierarchy obtains when a norm N1 cannot be incompatible with another norm (or set of norms) N2; if it is the case that N1 is in actual fact incompatible with N2, then N1 is materially invalid40. So in this case there is a relation of material hierarchy between N1 and N2, such that N2 is superior, in the specified sense, to N1; N2 is thus condition of material validity of N1. The obvious problem, here, is to make sense of the status of N2: when is it the case that N2 is actually superior, in the relevant sense, to N1? The most obvious answer – that N2 is superior to N1 if the former is condition of material validity of the latter – is, of course, questionbegging: indeed, being a condition of validity means being superior. We need a way out of the circle, and this can only be another norm, N3, that provides the required hierarchical ordering of N1 and N2. This will typically be done when N3 provides for a mechanism for the removal of N1 in case it conflicts with N2 (for instance, a system of judicial review of legislation). Accordingly, a material hierarchy between N1 and N2 obtains when a third norm (or set of norms) N3 states that in cases of conflict between N1 and N2, N1 shall be declared null and void. So, it is a norm of the kind of N3 that allows to – actually, it is N3 that establishes the material hierarchy between N1 and N2: absent N3, there would be no criterion whatsoever to the effect that N2 is superior to N1. In the terms of the example above, it is the existence of a system of judicial review of legislation that allows to claim that the constitution is hierarchically superior, in this sense, to legislation. Absent such a system, there would not be a relation of material hierarchy between legislation and the constitution – but there still could be a structural hierarchical relation, if it is the case that the conditions of valid enactment of statutes are regulated by the constitution. A logical hierarchy obtains when a norm (or set of norms) N1 has the function of regulating the application of other norms N2. For instance, a norm N1 that expressly abrogates or derogates to a norm N2, is hierarchically superior, in this sense, to N2. A semantic hierarchy obtains when a norm regulates the interpretation of some sources41. An axiological hierarchy obtains when one norm (or set of norms), is deemed more important in respect to another norm (or set of norms). For instance, legal principles are usually deemed more important than detailed rules (principles can make rules defeasible). Normally, and absent a material hierarchy to the same effect, the operation of an axiological hierarchy will consist in a judgment of preference or of applicability between the norms involved. So, if N 1 is considered superior, in this sense, to N2, the consequence will be the application of N1, without In a similar vein, M. Adler, M. Dorf, ‘Constitutional Existence Conditions and the Constitution’, talk of ‘existence conditions’ provided by the constitution to infra-constitutional sources (i.e., the constitution states the conditions in accordance to which infra-constitutional sources can count as valid instances of the relevant typesource). 39 Cf W. Waluchow, ‘Four Concepts of Validity’, p. 137: “failure to observe a condition for the valid exercise of a Hohfeldian power of law creation must, as a sheer conceptual matter, be a nullity”. 40 According to M. Adler, M. Dorf, ‘Constitutional Existence Conditions and the Constitution’, in this case N2 acts as a ‘application condition’ of N1. 41 On ‘secondary rules of interpretation’, see W. Waluchow, Inclusive Legal Positivism. 38 resorting to a declaration of invalidity of N2. N2 will be just ‘set aside’ for the instant case, but it will still be in force in the legal system, and potentially applicable in another case in which it does not conflict with N142. An axiological hierarchy can coexist with a material hierarchy to the same effect – this is the normal way to understand the relation between a rigid constitution and legislation in a system with judicial review. In this case, legal actors may be confronted with the decision of giving effect to the material hierarchy (= declaration of invalidity of the inferior norm that conflicts with the superior one), or to the axiological hierarchy (= giving effect to the superior norm and setting aside the inferior one, with a declaration of invalidity). But sometimes an axiological hierarchy can be established absent a material hierarchy to the same effect – indeed, it can be established between norms that have the same status as far as the material hierarchy is concerned (more on this below, sec. 4). 4. Sources, Normative Hierarchies, and Legal Interpretation Now that we have shed some theoretical light (or so the author hopes) on some important jurisprudential concepts, as well as on the various sense and types of normative hierarchies that operate in legal systems, we are in a better position to grasp the many ways in which legal interpretation (or legal reasoning more generally) actually shapes, or concurs in shaping, the relevant legal sources and the hierarchical relations – the other main aim of this paper. Recall that the backdrop of this discussion will be the widespread cultural and ideological assumption that legal sources and their hierarchies are the objective starting point of legal interpretation, something on which the interpreter has no say, no decisive power – quite to the contrary, legal sources and their hierarchical ordering is a given, an objective constraint for the interpreters. We have referred to this as the ‘standard picture’ of adjudication (see sec. 1 above). I will make to kind of remarks, here: one pertaining to the relation between sources as such and interpretation, the other pertaining to the relation between normative hierarchies and interpretation. (I will separate the two kinds of remarks for convenience’s sake, but they are actually interrelated on many accounts.) The first remark is, generally put, that the relation between legal sources and legal interpretation is not ‘unidirectional’, as it were, but indeed ‘bidirectional’. A unidirectional account is exactly the one that is assumed by the standard picture of adjudication: the interpreter merely acknowledges, as a matter of objective fact, the existence of some sources, and then proceeds to interpret it (the only margin of discretion for the interpreter, if such a margin indeed there is, lies with the choice and the operation of the various canons of interpretation). On the contrary, I will stress here the case for a bidirectional account of the relation between legal sources and legal interpretation: it is not the case that legal interpretation takes place not only on independently established legal sources. To begin with, some amount of legal interpretation is actually required already at that stage of legal reasoning where the interpreter ‘finds’ and selects the legal sources that are relevant for his argument43. Indeed, since (as we have seen above, sec. 2) a legal source is normally a document enacted as the outcome of a certain procedure, and since this procedure is normally regulated by several legal norms, the judgment that the item S1 is a valid legal source will normally presuppose a) having interpreted the relevant power-conferring norms (i.e., the relevant norms that provide the conditions of formal validity for the source in question – the 42 The establishment of an axiological hierarchy is an apt description of what happens, for instance, when a court resorts to ‘ad hoc balancing’ between competing constitutional principles. 43 Dworkin, Troper (una teoria realista), norms that superior from the point of view of the relevant structural hierarchy); b) having ascertained that the item in question actually fulfils the relevant conditions of formal validity44. Individuazione di disposizioni:; il combinato disposto Establishing type-sources Establishing token-sources ; l’abrogazione tacita; azzeramento del valore precettivo di un certo testo (qualificazione del testo come ‘non-fonte’, sua incapacità di esprimere norme, di produrre effetti giuridici) Binding and persuasive sources Distinzione tra fonti vincolanti e permissive (sfumata e graduale): J. BELL, Comparing Precedent, pp. 1254-1255; F. SCHAUER, Thinking Like a Lawyer, p. 80. So, theoretical and interpretive disagreement about legal sources may involve either the status of something as a legal source in the sense of a token-source, or – even more radically – its status as a type-source45. But indeed, legal interpretation may not only establish legal sources as such, but may also establish normative hierarchies as well. Establishing axiological hierarchies Establishing material hierarchies Formal and material constitution Rules and principles Principi costituzionali supremi, unconstitutional amandments Diritto interno diritto EU in Italia 5. Conclusions: Freedom and Constraint in Legal Argumentation 44 Adler-Dorf I understand in this second sense Ronald Dworkin’s challenge to legal positivism based on the pervasiveness of theoretical disagreements in law (see R. Dworkin, Law’s Empire): I take Dworkin as pointing here not merely to interpretive disagreements on the meaning and validity of specific legal sources, but on the status itself of certain things as sources of the law – for instance, principles and other moral arguments. On this, see A. Dolcetti, G.B. Ratti, ‘Legal Disagreements and the Dual Nature of the Law’. 45 Bibliography Besson S., ‘Theorizing the Sources of International Law’ Bobbio N., Giusnaturalismo e positivismo giuridico, Culver K., Giudice M., Legality’s Borders. An Essay in General Jurisprudence, OUP, Oxford, 2010. Dickson J., ‘Interpretation and Coherence in Legal Reasoning’, in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2001 (revised version 2010). --, ‘How Many Legal Systems? Some Puzzles Regarding the Identity Conditions of, and Relations between, Legal Systems in the European Union’, Problema. Anuario de Filosofia y Teoría del Derecho, 2, 2008, pp. 9-50. --, ‘Towards a Theory of European Union Legal Systems’, in J. Dickson and P. Eleftheriadis (eds.), Philosophical Foundations of European Union Law, OUP, Oxford, 2012, pp. 25-53. Hart H.L.A., The Concept of Law Koskenniemi M., ‘Hierarchy in International Law: A Sketch’, European Journal of International Law, 8, 1997, pp. 566-582. MacCormick N., ‘Coherence in Legal Justification’, in A. Peczenik (ed.), Theory of Legal Science, Reidel, Dordrecht, 1984, pp. 235-251. Merryman J.H., The Civil Law Tradition, Pino G., ‘Legal Positivism in Contemporary Constitutional States’ Raz J., ‘Legal Positivism and the Sources of Law’, --, ‘Legal Reasons, Sources and Gaps’, Spaak T., The Concept of Legal Competence. An Essay in Conceptual Analysis, Dartmouth, London, 1994. --, ‘Explicating the Concept of Legal Competence’, in J.C. Hage, D. von der Pfordten (eds.), Concepts in Law, Springer, Dordrecht, 2009, pp. 67-80. --, ‘Legal Positivism and the Objectivity of Law’, Analisi e diritto, 2004, pp. 253-268. Waldron J., “Partly Laws Common to All Mankind”, --, ‘International Law: “A Relatively Small and Unimportant” Part of Jurisprudence?’, Weiler J.H.H., Paulus A., ‘The Structure of Change in International Law or Is There a Hierarchy of Norms in International Law?’, European Journal of International Law, 8, 1997, pp. 545-565. von Wright G.H., Norm and Action,