Fulltext

advertisement

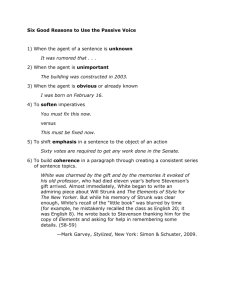

How Are George Orwell’s Writings a Precursor to Studies of Popular Culture? Abstract George Orwell is known as an acclaimed novelist, essayist, documentary writer, and journalist. But Orwell also wrote widely on a number of themes in and around popular culture. However, as During (2005) observes, even though Orwell’s writings might be considered as a precursor to some well-known themes in studies of popular culture his contribution to this area still remains relatively unacknowledged by others in the discipline. The aim of this paper is simply therefore to provide a basis to begin to rethink Orwell’s contribution to contemporary studies of popular culture. It does so by demonstrating some comparable insights on culture and society between those made by Orwell and those found in the work of Bakhtin, Bourdieu, and Deleuze. These insights are also related to four main areas of discussion: debates in contemporary cultural studies about the contested pleasures of popular culture and experiences; the relationship between language and culture; how social class needs to be defined not just economically but also culturally; and how one might escape cultural relativism when writing about popular culture. The paper concludes by suggesting that Orwell is a precursor to contemporary studies of popular culture insofar that some of the cultural themes he explores have become established parts of the discipline’s canon. Key words: George Orwell; language; nomad; pleasure; popular culture; social class Contact Information: John Michael Roberts, Department of Sociology and Communications, Brunel University, Uxbridge, Middlesex UB8 3PH, United Kingdom Email: John.Roberts@brunel.ac.uk Published in Journal for Cultural Research 2014, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 216-232, 1 Introduction It is sometimes said that George Orwell stands in the tradition of a peculiarly English conservative approach to studying popular culture, whose luminaries include writers such as F. R. Leavis. In this tradition ‘mass’ culture is criticised for duping people, justifying in the process the need for elite culture to overcome this herd mentality (Johnson 1979: 93-149). In his critical introduction to cultural studies, however, Simon During suggests that Orwell actually stands in a radical twentieth century cultural tradition that attempts to expose the manner in which certain social groups remain ‘invisible’ in dominant cultural beliefs and practices. Orwell for example tries to show how working class culture contains seeds of an alternative and often defiant belief system to that of dominant cultural mores of his day. During thus claims that Orwell, ‘produced work similar in some way to contemporary cultural studies but in different institutional settings and often with relatively little acknowledgment’ (During 2005: 35). Certainly some leading figures in the establishment of cultural studies hold both attitudes towards Orwell, seeing him as a conservative cultural commentator and as a precursor to a more sophisticated analysis of popular culture. Richard Hoggart for example chides Orwell for having a misty-eyed view of working class culture as seen through ‘the cosy fug of the Edwardian music-hall’ (Hoggart 1971: 17), but then later in the same book draws approvingly on Orwell’s description of working class attitudes to the ‘purposiveness of life’, particularly their popular beliefs on free will and the individual (Hoggart 1971: 95). Raymond Williams is arguably even more ambiguous in his attitude 2 towards Orwell. In Culture and Society, published originally in 1958, Williams praises Orwell as ‘a fine observer of detail’ (Williams 1983: 286) about popular culture, as somebody who uses language to further the cause of liberty and truth (Williams 1983: 288) and who does so through character traits of being ‘brave, generous, frank and good’ (Williams 1983: 294). Fast forward some years later and Williams is markedly more hostile towards Orwell. His ‘disgraceful attack’ on pacifists and revolutionaries during the Second World War causes Williams to declare that he can no longer read Orwell (Williams 1981: 385).1 Perhaps the ambiguous reception that Orwell has received in studies of popular culture is one reason why there have been few attempts to explore his contribution to themes in the discipline. Turner for instance devotes a chapter of his book to ‘the British tradition’ in cultural studies without once mentioning Orwell (Turner 1990: chapter 2), which is true also of a similar book by Barker (2008). Strinati (2004) mentions Orwell but only to suggest how he is principally worried by how ‘Americanisation’ violates English popular culture and working class communities, while Rojek (2007: 113) briefly alludes to Orwell in relation to cartoon animation but makes no further substantive observations about his numerous writings on popular culture. Some writers on culture and popular culture therefore take us tantalisingly close to explaining why Orwell might be considered to be an important forerunner to contemporary studies of popular culture although clearly they do not take us far enough, including During who only hints at Orwell’s achievements in this respect. But if it is the 3 case, as Hartley (2003: chapter 2) notes, that early- to mid-twentieth century British literary studies helped in the formation of contemporary cultural studies through works that took cultural questions seriously and which were printed in affordable books, it still remains a mystery exactly what Orwell’s contribution might be for a serious and scholarly consideration of popular culture, or why this famous writer might be said to be a forerunner to the investigation of popular culture. The purpose of this discussion is to take seriously During’s claim that Orwell’s work stands as a relatively unacknowledged precursor to later studies of popular culture by investigating this issue in more depth than is customary amongst scholars. This task will not however be carried out through a historical analysis, which has anyway already been partly accomplished in different ways by Bounds (2009) and Newsinger (2001). Instead the paper adopts a different approach. It takes three distinct but interrelated areas that have become established in scholarly accounts of popular culture and then seeks to map out how Orwell also explores these areas in his own unique manner. By proceeding in this way it becomes possible to examine whether Orwell’s analysis of culture finds unacknowledged parallels and similarities in contemporary studies of popular culture. The paper therefore has at least one original slant to it to the extent that there has not been a comprehensive discussion of Orwell’s contribution to some of the themes found in popular culture studies.2 In this respect the paper has three main sections. The first section outlines how Orwell’s approach to popular culture is similar to the idea presented by many cultural theorists that popular culture is complexly structured by 4 different social forces that in turn give rise to contested meanings in and around cultural objects. In particular, Orwell would without doubt agree with those theorists who argue the contested nature of popular culture is due in part to the pleasure popular culture gives to people to create their own meanings in society. This line of reasoning is continued in the second main section where Orwell’s views on language and culture are analysed. By drawing on the work of Mikhail Bakhtin and his theory of language as a dialogic process, we will see that for Orwell words are always mediated by conflicting ‘accents’ that refract and internalise various social processes. To stabilise these dialogic conflicts a hegemonic power aims to construct ‘monologic’ language forms; forms that Orwell is alert to and indeed seeks to expose. But far from reducing social life to language, the paper argues that for Orwell words and utterances are always mediated through non-discursive forms such as that of social class. This point takes us onto the third main section, which revolves around the relationship between social class and culture. Here, we see that Orwell explores social class as a cultural phenomenon in much the same way as is found in the work of some contemporary cultural and social theorists. In particular, Pierre Bourdieu’s work on the relationship between culture, the body and class will be especially relevant in fleshing out Orwell’s insights on similar issues. Indeed, this discussion will open up a space to show how other cultural and sociological categories apart from language, such as the body and space, are crucial elements to his analysis of social class. 5 But another important question still remains unanswered and one which has troubled critics. To what extent can Orwell escape cultural relativism in order to make critical observations of other social identities outside the confines of his own middle-class context? Certainly, Orwell has been accused of simply imposing his own middle-class sensibilities on those he writes about. By drawing on Deleuze and Guattari the fourth section of the paper argues that one possible answer to this dilemma is to see Orwell as a ‘nomad’ who manages to assemble some of the ‘molecules’ associated with other social identities into his own identity. The paper concludes by suggesting that Orwell is a precursor to contemporary studies of popular culture insofar some cultural themes he explores have become established parts of the discipline’s canon. The conclusion therefore also rejects a common criticism which states that Orwell’s view of culture and society is based in a naïve and simplistic empiricism. The Contested Pleasures of Popular Culture Storey (2012) observes that to find an agreed view about what constitutes popular culture is a fairly arduous task because different theories abound. For example, one view suggests that popular culture is that which is mass produced whereas high culture – opera, Shakespeare, and the like – is endowed with more creative and aesthetic qualities. On this reckoning, popular culture is deemed to be rather worthless next to the more superior aesthetic moral qualities of high culture. However, there is another critical take on popular culture which is arguably best represented by Fiske’s claim that popular 6 culture is the medium where the production of abstract materials of the culture industry are reinvested with new meanings taken from everyday life (Fiske 1989). People therefore have a great capacity to imagine culture in innovative ways through language, symbols, texts, and so on, and to generate new cultural meanings over and above that which is often the preferred dominant way of using culture (see also Lewis 2002: 13). One important attribute of popular culture is its ability to give people pleasure as they recreate new meanings for cultural objects. Popular culture is thus enjoyable and summons up different types of emotional encounters: love, excitement, anguish, laughter, joy, enthusiasm, tension, and so on. Such emotions and passions are important because they engender a fervent commitment towards cultural products by helping to arrange, express, and manage our everyday feelings (Grossberg 1992; Street 1997). Pleasure, in this respect, is often gained by people making consumer products functional in their daily lives. Whereas elite culture can afford to play no function whatsoever in daily life for those who follow it (think for example of ballet), popular culture, a typical example being football, becomes pleasurable to the extent that it is indeed part and parcel of everyday life (Fiske 1989: 57; see also Fiske 1993: 68). Orwell views popular culture along comparable lines. In The Lion and Unicorn he suggests for example that popular culture ‘is something that goes on beneath the surface, unofficially and more or less frowned on by the authorities’ (Orwell 1970a: 78). Like other cultural theorists discussed later in the paper, Orwell believes that part of the reason why authorities frown on popular culture rests in the pleasurable ‘unofficial’ subversion 7 that it hands to ordinary people. Seaside postcards, for example, contain bawdy humour and yet for Orwell they also mock conservative sentiments and make sure that ‘on the whole, human beings want to be good, but not too good, and not quite all the time’ (Orwell 1970a: 194). But there is more to Orwell’s view of popular culture than merely taking pleasure in everyday objects. Indeed, Orwell appreciates that popular culture operates in part through a complex semiotic process of negotiation between audience and text. Of course, the use of semiotics to analyse popular culture has a distinguished history in cultural studies. One approach maintains that a text emits a series of ‘connotative’ codes that frame the way the text is read by bringing together various meanings and certain preferred ways of reading images or narratives. For example, in her early work conducted during the 1970s and 1980s McRobbie (1991) found that British magazines for teenage girls embodied a variety of codes and messages for their respective readership. One such magazine, Jackie, embodies a code which stipulates that romance is far more relevant for girls than sexuality. Through this code, young women in Jackie are formed into three main types: the blonde, quiet, timid, loving, and trusting girl who either gets the boy in the end or is abandoned; the wild, fun-loving brunette who resorts to plotting and conniving so that she gets the man she wants; and lastly there is the non-character, the ‘ordinary’ girl (McRobbie 1991: 101). Like McRobbie, Orwell is similarly interested in how popular texts create specific codes how to ‘read’ them. But he is also fascinated by the way in which audiences actively ‘decode’ messages and reinvest them with alternative 8 meanings. Orwell’s approach on this matter is especially clear in his essay on boys’ weekly newspapers. Boys’ weeklies are categorised by Orwell into two classes. The first tells stories about public school life, while the second deals exclusively with tales of adventure. Although there remain obvious differences between the two, a couple of messages nevertheless recur with some regularity in both. ‘Nothing ever changes, and foreigners are funny’ (Orwell 1981: 484). In a 1939 weekly called Gem Frenchman are still ‘Froggies’ and Italians still ‘Dagoes’. Wun Lung, a Chinese boy, ‘is the nineteenth-century pantomime Chinaman with saucer-shaped hat, pigtail and pidgin-English’ (Orwell 1981: 484). The same is true for adventure stories. Once again Chinese characters are sinister pigtailed opium-smugglers – ‘no indication that things have been happening in China since 1912’ (Orwell 1981: 490). Codes therefore appear to transmit conservative themes. Importantly, though, these are not merely simple conservative messages – what Hall (2006: 171) terms the dominant-hegemonic viewpoint – but are on the contrary messages which become embedded in specific narratives and plotlines that boys recognise. A conservative bias is certainly conveyed, but ‘in a completely pre-1914 style, with no Fascist tinge’ (Orwell 1981: 484). Take patriotism. This ideal is evident in the papers, explains Orwell, although it has nothing to do with power politics or ideological warfare. Patriotism is, rather, embodied in other codes like ‘family’ that the boys can immediately identify with. This then is a subtle form of patriotism which is ‘more akin to family loyalty’. It is the type of patriotism which prompts people to expect ‘that what happens in foreign countries is none of their business’ (Orwell 1981: 485). 9 For Orwell, these narratives demonstrate that the publishers of such weeklies always have to react to the everyday lives of their readership – they have to engage in a negotiated process with their audience. Orwell notes for example that boys’ weeklies contain traces of alternative readings that move beyond a small ‘c’ conservatism. After all, the magazines encourage their readers to connect with different characters and this gives readers a space to transgress distinctive moral codes embodied in single characters in the magazines. Instead readers enjoy the potential to rework a number of traits from a number of characters in new ways. This contested pleasurable experience implies that the publishers cannot necessarily expect boys to read the conservative messages as intended. It therefore appears to be the case that Orwell is aware that texts and language provide resources for ordinary people to create their own oppositional codes that reject dominant narratives (see also Hall 2006: 173). Bounds goes as far as to suggest that Orwell believes popular cultural objects like boys’ weeklies are dialogical and polysemic (Bounds 2009: 69). However, we have still yet to demonstrate this latter point in enough detail. The next section therefore turns to the work of Mikhail Bakhtin to address this issue. Bakhtin’s ideas seem especially pertinent in this respect. As Fowler (1995) indicates, Bakhtin’s argument that language is not an impartial abstract linguistic structure but is instead comprised by a living and breathing collision of popular experiences and ideological utterances chimes well with Orwell’s view of language. Moreover, Bakhtin’s work on popular culture and language has been an important reference point for many contemporary cultural theorists in making sense of everyday lived experiences (see 10 McGuigan 1992) and they therefore provide another extremely useful perspective on how some of Orwell’s writings fit into the canon of cultural studies. Language, Culture and Power One of Bakhtin’s key insights is that language is inherently dialogical, heteroglossic, and multiaccentual. In practice, this means that everyday language use is contradictory in scope to the extent that it refracts different points of views, different social classes, different ideologies, different identities, and so on. And so working class speech utterances, obviously, may not hold the same understanding of a specific word as their middle class counter-part. ‘As a result’, claims a colleague of Bakhtin’s, Voloshinov, ‘differently orientated accents intersect in every ideological sign’ (Voloshinov 1973: 23). For Bakhtin, this also implies that utterances exist in a structured reality and as such obtain a specific identity at different levels of ‘stratification’ (see Bakhtin 1981: 288292). For example: Actual social life and historical becoming create within an abstractly unified national language a multitude of concrete worlds, a multitude of bounded verbalideological and social belief systems (Bakhtin 1981: 288; see also Bakhtin 1984a: 30). Dialogue therefore operates for Bakhtin in real socially-mediated contexts alive to spoken language and different ‘accents’, rather than in the confines of asocial linguistic sentence structures that can be repeated ‘in completely identical form’ (Bakhtin 1986: 108). 11 Orwell makes a comparable distinction between written and spoken language. In his essay ‘Propaganda and Demotic Speech’ Orwell goes as far as to note that while the English language has a huge array of words used in writing, many of these actually ‘have no real currency in speech’ (Orwell 1970b: 165). His thinking on this matter is part of his wider belief that one potential of language is to simplify our everyday practices and experiences. Words have the capacity to streamline the complex nature of our motives and thoughts which are derived from our everyday practices (see Orwell 1970a: 17). But this point carries a further implication for Orwell. A group whose goal is to gain hegemonic dominance will also endeavour to ‘streamline’ everyday practice through its own language-forms. In more Bakhtinian terms, a group striving for hegemony must try to ‘accent’ the dialogical nature of key utterances in a way that favour its own social and political agenda. This ‘monoglossic’ dominant practice therefore attempts to articulate a type of linguistic unification in and against the lived experience and heteroglossic utterances of centrifugal local forces (Bakhtin 1981: 270; see also Voloshinov 1973: 23). By so doing, monoglossic utterances make sure that their uniaccentual meaning conceal and gloss over meaning alive to conflict, contradiction, and social struggle. Even though Orwell obviously never uses the term ‘monoglossia’, an illustration of such language forms which is extremely close to Bakhtin’s meaning can be found in his famous essay, ‘Politics and the English Language’. Here, Orwell ruminates on the relationship between politics, power and language. At one point he says: 12 (P)olitical language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging, and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenceless villages are bombarded from the air, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called ‘pacification’ (Orwell 1981: 741). So, the word rebuked by Orwell – ‘pacification’ – is an ideological construct which deceives and misinforms, and whose surface appearance helps to mask a deeper social reality. ‘Pacification’ in this instance is a uniaccentual word devoid of heteroglossic diversity insofar that as it seeks to ensure that people repeat its uniaccentual meaning without critical reflection. Linguistically, one common way that monoglossia occurs is by transforming verbs into nouns to create nominalizations so that a sentence or statement is left naked in terms of truth-value or tense. Nominalizations are therefore far more likely to render a process as a ‘neutral’ object or product, leading to its uniaccentual status (see also Hodge and Fowler 1979 for similar observations). Orwell explains it thus: The keynote is the elimination of simple verbs. Instead of being a single word, such as break, stop, spoil, mend, kill, a verb becomes a phrase, made up of a noun or adjective tacked on to some general-purposes verb such as prove, serve, form, play, render. In addition, the passive voice is wherever possible used in preference to the active, and noun constructions are used instead of gerunds (by examination of instead of by examining) (Orwell 1981: 738; original emphasis). For Orwell, nominalizations are highly ideological. They tend to elicit ways of thinking and writing that bracket out real social processes and so engender a belief that language 13 can be studied as an independent realm at some distance from its use in everyday and ordinary social contexts. Just as Marx and Engels once said that language becomes an ideological construct in the service of power when words are seen to exist as an independent realm ‘in which thoughts in the form of words have their own content’ (Marx and Engels 1998: 472-3; see also Cook 1982), so Orwell similarly believes that a language form which admits to no social or historical mediations ‘bears the same relation to writing real English as doing a jigsaw puzzle bears to painting a picture’ (Orwell 1970b: 135). Orwell also clearly believes that language is dialogic and heteroglossic and thus represents an important point of struggle over how the world is represented and encoded through particular words in different social contexts. This is graphically illustrated during Orwell’s time fighting for the Spanish Republic against Franco’s fascists. When he joins the Republican militia in December 1936 Orwell soon detects the embryo of a community in which a classless society might emerge – a society where ‘the word “comrade” stood for comradeship and not, as in most countries, for humbug’ (Orwell 1989a: 83). The word – ‘comrade’ – when used as an utterance at real dialogic events in Spain during this period subsequently reveals something truly remarkable about social class distinctions: people fighting for freedom and the Spanish Republic no longer have to endure ‘privilege and boot-licking’. Servile forms of speech are now reprimanded together with other social inequalities such as unemployment and high living costs. At last Orwell discovers a living example of socialism in practice: ‘human beings were trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine’ (Orwell 14 1989a: 4). ‘Comrade’ is a heteroglossic utterance at this particular event because it exposes real contradictions and class struggles evident in Spanish society during this point in time. ‘Comrade’ is also illustrative of how utterances embody evaluative expressions that establish hierarchical relationships and social divisions as well as relationships of solidarity between and within social groups and social classes. So, dialogue and utterances are not only concerned with disputes over the ‘correct’ use of language but also convey a number of cultural and social issues such as bodily appearance, intonation, the use of public space, social taste, and so on. Bakhtin and Voloshinov recognised as much, which is one reason why they believed that the battle over hegemony and power was not just a struggle over language but also part of wider struggle between classes (see for example Bakhtin 1984b: chapter 5; Voloshinov 1973: 23). This is also the view of Pierre Bourdieu who shares some notable similarities with Bakhtin on these issues. He too says that language not only embodies codified authoritative commands based on deeply engrained binary oppositions (e.g. some in society are categorised as ‘strong’, others as ‘weak), but that language expresses social divisions through factors such as intonation (Bourdieu 1984: 191 and 472). Furthermore, Bakhtin and Bourdieu tell us that even though language is an inherently social phenomenon it is still only one albeit important element of social life. For example, and as Fiske (1989: 52-4) observes, Bakhtin and Bourdieu share a commitment to revealing the potential of bodily excess in and against dominant power relations; for instance how 15 sporting events or public carnivals enable people to momentarily engage in physical and public acts of popular celebration and inversions of governing mores which draw on but also go beyond convetional language forms (see Bakhtin 1984b; Bourdieu 1984). Orwell is similarly concerned not to simply reduce the complexities of social life to language alone. Without doubt, investigating how language operates in everyday life to create specific identities is important to any critical analysis of society, but one must equally grasp how hegemony moves through many other cultural and social forms. One particular set of social relations Orwell dwells upon in this respect is that of social class. While Bakhtin similarly explores social class, it is in fact Bourdieu who of course devotes a considerable amount of his research time to investigating the relationship between culture and class. This is why we now turn to see how Bourdieu and Orwell examine the relationship between social class and culture. Social Class and Cultural Identity Recent years have witnessed a growing trend for sociologists to examine social class in terms of culture. While not denying the importance of other sociological definitions, such as Weberian accounts (see Erikson and Goldthorpe 1993) that define social class in terms of the difference between employment conditions (e.g. promotional prospects) and employment relations (e.g. the control one experiences at work), social and cultural theorists have started to enquire into the cultural significance of class. For instance, they 16 suggest that class divisions often operate along lines of cultural distinctions like lifestyle and taste. Collectivities around social class thereby give way to cultural and symbolic markers of difference, as in difference of taste. Indeed, according to Skeggs (2003), this often leads working class people to ‘dis-identify’ with belonging to the working class. Skeggs finds in her own study that the working class women she interviewed frequently internalise the cultural marker of middle class ‘respectability’. By doing so these very same women reject working-class cultural categories for themselves because they feel these stigmatise them as not being respectable (see also Bottero 2004; Hebson 2009; Savage 2000). In order to draw out the cultural attributes of class relations many theorists have turned to the work of Bourdieu. Especially useful here is Bourdieu’s concept of ‘habitus’. According to Bourdieu, the habitus ‘enables an intelligible and necessary relation to be established between practices and a situation, the meaning of which is produced by the habitus through categories of perception and appreciation that are themselves produced by an observable social condition’ (Bourdieu 1984: 101). A habitus comprises a set of embodied behaviours and tendencies that teach us over time how to act and react in particular social fields (e.g. an artistic field, an economic field, an educational field, or a religious field). Each social field offers up objective constraints and resources for people to use and to struggle over. These resources range from economic capital (e.g. wealth), cultural capital (e.g. qualifications), symbolic capital (e.g. prestige), and social capital (e.g. social networks). The habitus is therefore both a ‘structuring structure’ that arranges practices and perception of practices, and a ‘structured structure’ which internalises and 17 reproduces social constraints, divisions, and opportunities from different social fields (Bourdieu 1984: 166). While Orwell’s writings on social class pose some difficulties, not least his eagerness to focus on the industrial working class to the detriment of other working class groups and identities (see Clarke 2007: 55-62), it is nevertheless true to say that he also engages in a cultural analysis of social class that makes some interesting connections with Bourdieu’s work. One illustration can be located in The Road to Wigan Pier where Orwell observes: Economically, no doubt, there are only two classes, the rich and the poor, but socially there is a whole hierarchy of classes, and the manners and traditions learned by each class in childhood are not only very different but – this is the essential point – generally persist from birth to death...; you find millionaires who cannot pronounce their aiches; you find petty shopkeepers whose income is far lower than that of the bricklayer and who, nevertheless, consider themselves (and are considered) the bricklayer’s social superiors; you find public-school boys ruling Indian provinces and public-school men touting vacuum cleaners (Orwell 1989b: 208-209). This passage demonstrates that for Orwell social class is a complex mixture of economic, social, and cultural capital which combine in distinctive ways in specific contexts, or fields. They gain their unique identity only in relationship with one another and it makes no sense to analyse them separately. As Orwell indicates, a working class person might be a millionaire and therefore officially belong to the upper echelon of society and yet still retain working-class cultural capital in how they speak in particular social fields and 18 sub-fields. They will therefore struggle to gain middle-class symbolic capital in these fields. ‘Having a million’, Bourdieu informs us, ‘does not in itself make one a millionaire’ (Bourdieu 1984: 374). Orwell, like Bourdieu, therefore focuses on the vast and multiple practices employed by ordinary people that equip them to negotiate paths around and through complex social processes. Orwell makes five further points on these issues. First, he is aware that ordinary people experience social class through a phenomenological experience of something akin to a habitus (although of course Orwell does not use this exact term). Second, he highlights how resources help people to creatively develop their own embodied class identity in and against dominant power relations. Third, Orwell also wants to draw attention to the way in which specific resources enable ordinary people to spatially negotiate their way through power relations surrounding social class that become entrenched in empirical places within specific social fields. Fourth, he is keen to stress that these processes are contradictory and dialogic. While resources might provide members of the working class to resist power relations, for example, they might also encourage the very same people to accept hegemonic power relations. Finally, he is sensitive to the ways in which resources of class (cultural capital, for example) impact on how one is reflexive about one’s own ideological viewpoint and social position. Arguably, these five points taken together make Orwell’s observations on social class distinctive in cultural studies, and, indeed, sociology, because it is rare to find them being discussed in concert by a sole author. They will now be expanded upon. 19 If we turn to the first point, Orwell suggests that social class is based in part on a practical feel for a social context that is both conscious and unconscious. Orwell draws on a popular expression of his day – ‘to make the best of things on a fish-and-chip standard’ – to describe these processes. For Orwell this expression sums up for him the ability of working-class members to ‘make do’ with resources at hand in order to retain a sense of self-worth in the face of social and economic inequalities and injustices. The long trek to Wigan Pier shows Orwell that although their lives are on no account desirable, the workers he met have made the best that they could in the circumstances. The Wigan workers, Orwell announces, ‘have neither turned revolutionary nor lost their self-respect; merely they have kept their tempers and settled down to make the best of things on a fishand-chip standard’ (Orwell: 1989b: 83). Orwell’s observations are reminiscent of what Bourdieu suggests are some of the main characteristics of the habitus. Over time the habitus internalises the objective constraints and resources in different social fields while generating structured dispositions for individuals to occupy in particular fields. A habitus thereby creates ‘classifiable practices and works, and the capacity to differentiate and appreciate these practices and products (taste), that the represented social world, i.e., the space of life-styles, is constituted’ (Bourdieu 1984: 166). A ‘fish-and-chip standard’ can be seen as representing a habitus for Wigan workers. It denotes a set of relatively durable and structured dispositions that these workers have settled into over a period of time and which enable them to make sense of their surrounding circumstances and their own identity. And because the workers 20 have made the best they can in their circumstances they have also adapted objective structural patterns over time to fit their own lived experiences. As Bourdieu notes elsewhere, a habitus is constantly open to daily experiences and ‘therefore constantly affected by them in a way that either reinforces or modifies its structures’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 133). People subsequently display signs of reasonable behaviour in as much that they are not ‘fools’ or ‘deluded’ but gain a practical feel of what ‘unquestionably imposes itself as that which “has” to be done or said’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 130). Once people gain this practical feel of both their objective circumstances and internal dispositions they will then engage in strategic actions about how to anticipate and shape their present and future circumstances. For example, Orwell observes that the widely held ‘fish-and-chip standard’ amongst Wigan workers carries with it traces of ‘vague’ socialist ideals – ‘justice and common decency’ – mixed in with popular culture. In this socialist vision the worst abuses are left out but life generally carries on much the same as before, ‘centring around...family life, the pub, football and local politics’ (Orwell: 1989b: 164). Here, then, we see the workers being ‘reasonable’ in adapting and shaping their habitus to suit their own lived experience within the constraints of objective relations. Following this, and second, if we agree with Bourdieu that cultural markers of social class are inscribed on the body, indeed they ‘help to shape the class body’ (Bourdieu 1984: 188), it is equally true to say that Orwell’s own analysis of social class takes account of this point in graphic form. The Road to Wigan Pier is littered with discussions 21 about how social class and popular experiences are played out on the body. The most well-known one sees Orwell on a train in Wigan. Looking out of the window he notices a young woman kneeling on the stones poking a stick up a wooden leaden waste pipe in an attempt to unblock it. As the train goes by the young woman glances up in the direction of Orwell and catches his eye. The sight of her body hands Orwell the information he requires to momentarily comprehend her experience: ‘She had a round pale face, the usual exhausted face of a slum girl who is twenty-five and looks forty, thanks to miscarriages and drudgery; and it wore for the second in which I saw it, the most desolate, hopeless expression I have ever seen’ (Orwell 1989b: 15). Destitution adorns her body, and conscious destitution at that for she ‘knew well enough what was happening to her’. In an oppressive atmosphere the body and its dispositions sums up a network of unequal class relations. Third, place, space, and power are an extremely important way of thinking about the relationship between class and cultural identity. As some contemporary geographers and sociologists suggest (e.g. Edensor and Millington 2009), place is often a significant cultural sign of class taste and class distinction. Middle class residents in a particular locality might for instance resort to certain utterances (e.g. ‘we’ live in a ‘nice’ area compared to the ‘rough’ estate down the road) in order to symbolically mark themselves off from other more working class localities (see Dowling 2009; Watt 2009). For Bourdieu place is indeed a vital point of analysis in this respect but so too is social space. Indeed, social space arguably presents a more insidious way to distribute power between individuals because it is less visible than empirical symbolic markers of place. Social 22 spaces, or ‘schemes of action’, are expressed in the social and cultural tastes experienced in the habitus and which then connect groups of people together in an actual place (Bourdieu 1984: 168). These social spaces often remain implicit but they nevertheless delineate specific social positions; ‘all the distinct and distinctive lifestyles which are always defined objectively and sometimes subjectively in and through their mutual relationships’ (Bourdieu 1984: 95). Orwell likewise observes that class and power operate through place and space (Tyner 2004), and that this produces a specific cultural identity. In one episode in Down and Out in Paris and London free tea and buns are handed out to homeless men in the place of a small tin-roofed shed in a side-street. But a price has to be paid. The men are expected to listen patiently to religious sermons from charity helpers, including kneeling down and praying. They therefore not only sit in a particular place but are also momentarily inhabiting a religious social field. At the same time different groups in this place occupy different social spaces which are in turn dependent on their respective habitus. A middle class lady in charge takes on a surveillance role and makes sure that all are active in the ritual. Less than willing to comply, the homeless men, in small ways, contravene although never totally escape these disciplining techniques. Often they resort to grinning and winking at each other when the lady looks away and bawdy jokes are muttered in hushed tones. Finally, when the prayers are eventually over, Orwell hears one of the men announce: ‘Well the troubles over. I thought them f___ prayers was never goin’ to end…you don’t get give much for nothing. They can’t even give you a two penny cup of tea without you go down on your f___ knees for it’ (Orwell 1989b: 143). The men are 23 quite conscious that even charity demands rules to be obeyed, duties to be performed, and social spaces to be occupied in spatial confines. Fourth, Orwell recognises that the complexity of these processes implies that while members of the working classes use the resources at hand to ‘resist’ power relations they also often internalise and reproduce power relations. Indeed, Orwell accepts that social identity is fluid so that individuals can adopt the outlook of a hegemonic power at one moment in time while ‘resisting’ it at another moment. To give just one illustration, many of the homeless in Down and Out in Paris and London often slipped into the discourse operated by the power-bloc. One homeless man, Paddy, admonished Orwell fairly severely when the latter criticised food wastage in the workhouse kitchen. ‘They have to do it’, he said. ‘If they made these places too comfortable, you’d have all the scum of the country flocking to them. It’s only the bad food as keeps all that scum away. These here tramps are too lazy to work, that’s all that’s wrong with them. They’re scum’ (Orwell 1989c: 200). Some of the workers he encountered likewise agreed with severl bourgeois convictions. Constitutionalism and legality were respected, ‘the belief in “the law” as something above the State and above the individual...’ (Orwell 1970a: 81). Again, such sentiments demonstrate how the habitus is a complex mechanism. On the one hand it operates to provide resources in order to shape and sometimes ‘resist’ one’s objective circumstances, while on the other hand it can adapt one’s dispositions to accommodate and submit to these objective circumstances (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992: 24). 24 Finally, Orwell is attentive to the way in which social class offers up specific resources which at the same time impact on how one reflects on the world. In particular, cultural and symbolic resources reproduce and reinforce class differences. In The Road to Wigan Pier Orwell asks his readers: ‘[I]s it ever possible to be really intimate with the workingclass?’ (Orwell 1989b: 106). He replies that it is not possible. ‘I do know that you can learn a great deal in a working-class home, if you can get there. The essential point is that your middle-class ideals and prejudices are tested by contact with others which are not necessarily better but are certainly different’ (Orwell 1989b: 106). Part of the reason why intimacy cannot be fully achieved is that class differences are bound up with distinct cultural and symbolic attributes which are hard to shake off – they are part of one’s social identity (Orwell 1989b: 149). Achieving full class intimacy inexorably demands suppressing one’s own habits and traits – or habitus in Bourdieu’s language – which is extremely demanding, if not impossible. But if this is the case how can the middle class Orwell possibly convey to readers the lived experiences of the working-class if he occupies a different class habitus to them? Or, more broadly, how can Orwell escape his own habitus to make meaningful analytical contact with any other social identities different to his own? Certainly it is a question that has also preoccupied other writers, most notably Raymond Williams, who in the end thought Orwell belittled the working-class a little too much for his liking (Williams 1981). It is to this question we now turn. 25 Beyond Cultural Relativism and Towards Nomadism In Cinema 1, Gilles Deleuze makes a favourable allusion to Bakhtin’s theory of the utterance. According to Deleuze, Bakhtin correctly states that language does not operate through two fully constituted subjects of enunciation of the reporter and the reported. It is rather a case of an assemblage of enunciation, carrying out two inseparable acts of subjectivation simultaneously, one of which constitutes a character in the first person, but the other of which is present at his birth and brings him onto the scene. There is no mixture or average of two subjects, each belonging to the system, but a differentiation of two correlative subjects in a system which is itself heterogeneous (Deleuze 1995: 75). This quote is noteworthy for two main reasons. First, it demonstrates a theoretical continuity between the work of Bakhtin and that of Deleuze. Both reject the idea that language is a ready-made abstract structure which is simply appropriated by an allknowing subject. They believe a more accurate description is one that highlights the nonsignificatory expressive potentials of utterances. Language exists as part of an assemblage between at least two individuals and therefore is always in a process of expressive becoming because it refracts the social relations surrounding and embedded in this assemblage. These social relations include social divisions, solidarity, and relationships of power. Second, the quote can be taken as an apt illustration of how Orwell manages to write about the lives of others without falling into cultural relativism. When discussing the 26 daily experiences of being homeless, working-class, a soldier in Spain, and so forth, Orwell momentarily merges his own embodied encounters and events with those he talks about. That is to say, he creates ‘a differentiation of two correlative subjects in a system which is itself heterogeneous’. He speaks about their lives through his own experiences of their lives in the persona of ‘George Orwell’. We now explore this point in more depth through Deleuze and Guattari’s writings. According to Deleuze and Guattari molar formations are assemblages that assume wellknown and relatively stable functions such as being a ‘woman’ or being ‘working class’ or social systems such as ‘capitalism’ or ‘the state’ (Delueze and Guattari 1988: 304-15). In this respect a molar formation might be said to encompass the habitus and social fields, a relatively stable set of engrained dispositions and distributions of constraints and resources Molecular particles, on the other hand, refer to heterogeneous expressive elements that when assembled together help to maintain a consistent identity for a molar formation (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 357). Molecules are expressive because they communicate to others how a molar formation is becoming in its identity. Molecules frequently alter their relationship with one another through ‘movement and rest, speed and slowness’ in a manner that is ‘closet to what one is becoming, and through which one becomes’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1988: 300). At the same time molecules engage in a process of ‘deterritorialisation’ going on here as an assemblage seeks out new molecules to link up to within the remit of a particular molar formation, or molecules break away from a molar formation to create a new assemblage. All of these processes lead to further relations of in/consistency. 27 But deterritorialisation also raises the possibility that molecules have somewhat of a ‘nomadic’ existence. Far from travelling in a straight line nomads instead travel across a number of boundaries and occupy a number of spaces. Indeed, nomads blur the boundaries between spaces by often being in two spaces at once. [Nomads are] without property, enclosure or measure. Here, there is no longer a division of that which is distributed but rather a division among those who distribute themselves in an open space – a space which is unlimited, or at least without precise limits (Deleuze 1994: 46). It is not too far off the mark to suggest that while Orwell believes that social class is inscribed and embodied in what might be termed as a class habitus, he also recognises that social identities are comprised by assemblages of different ‘molecules’. Indeed, it is this recognition that arguably allows Orwell to escape the spectre of cultural relativism. In Wigan Pier for example Orwell readily admits that as a middle class writer his identity is clearly different to the working class people he has met. As he says of his daily encounters with ‘the proles’: ‘However much you like them, however interesting you find their conversation, there is always that accursed itch of class-difference, like the pea under the princess’s mattress. It is not a question of dislike or distaste, only of difference, but it is enough to make real intimacy impossible’ (Orwell 1989b: 145). For Orwell, then, social class is an assemblage of ‘difference’ embodied in: 28 my taste in books and food and clothes, my sense of honour, my table manners, my turns of speech, my accent, even the characteristic movements of my body… (Orwell 1989b: 149). It is these ‘molecules’ of identity which imply that for a member of the middle class to pretend to share solidarity with the working class without at the same time addressing their different molecular assemblages simply creates a fictitious degree of sympathy. Nonetheless Orwell also recognises that it is different molecules that go to help create specific social identities break apart and momentarily become merged with other ‘molecules’ of social identity. Molecules that reproduce the molar formation of middle class identity can for instance break off and momentarily connect up with molecules of working class molar identities. What is interesting about Orwell is that he would seem to embrace and welcome this ‘deterritorialisation’ of his social identity. In fact, it is possible to say that Orwell paints a picture of himself as a nomad, as a traveller embarking on new journeys. Whether he is down and out amongst the homeless, in the trenches of Spain, or down a mine, Orwell deliberately sets out to disturb and unsettle his own middle class identity and to enter other strange landscapes. He thus allows his own molecular habits to be rearranged into a new assemblage. Thus the body is not merely an object upon which molar power relations are played out, but also represents a site where negotiations for new molecular bodily assemblages can be brought into being. This nomadic existence can be seen at greater length through an essay written in 1929 entitled ‘How the Poor Die’. Orwell recalls a stay in a Paris hospital for treatment to his 29 ‘bronchial rattle’. As he is not paying for his treatment he is reduced to the status of a ‘poor patient’ and thereby assembled by the molar formation of medical staff as a ‘specimen’. ‘It was my first experience of doctors who handle you without speaking to you, or, in a human sense, taking any notice of you’ (Orwell 1984: 394). Similarly as the gaze of the student doctors glide across his body Orwell observes: ‘It was a queer feeling – queer, I mean, because of their intense interest in learning their job, together with a seeming lack of any perception that the patients were human beings…’ (Orwell 1984: 395). But far from accepting their status as a medical object, Orwell concludes that the majority of the poor on the ward know the hospital is ‘a lousy place’ to visit. The attitude of the majority is, however, one of critical acceptance. ‘If you are seriously ill, and if you are too poor to go be treated in your own home, then you must go into hospital, and once there you must put up with harshness and discomfort, just as you would in an army’ (Orwell 1984: 399). Importantly, Orwell reaches his critical understanding of hospital treatment of the poor by talking about a personal and embodied event in his life and then reassembling this into a public issue. Orwell achieves this by situating his own embodiment within the distinct habits, repetitions and events he encounters within the hospital. This is Orwell the nomadic writer, entering a space that is different to his own middle class life. As such he leaves the ‘normal’ territory of his middle-class body and opens up his embodiment to that of the poor and to the medical profession. ‘Molecules’ of his embodied identity momentarily merge with some of the molecules evident in the sights, sounds, tastes, and 30 smells of the hospital and, in the process, ‘reterritorialises’ the assemblage of ‘George Orwell’, the critical socialist writer. Conclusion At the beginning of the paper it was noted that some see Orwell as a rather conservative social and cultural commentator whose traditional beliefs ultimately lead him to embrace a conformist rather than critical attitude. Wilkin for example suggests that Orwell’s dedication towards democratic socialism is tempered by his support for English Tory values like ‘decency, common sense and respect for custom, tradition and heritage’ (Wilkin 2012: 201). This cultural outlook is encapsulated in Orwell’s yearning for a return to the English countryside of 1910 where social classes are no longer at war with one another but exist in an amenable relationship. It is an image of an always in-the-past England rather than an image of what England has actually become (Wilkin 2010: 1048). Like many conservative writers Orwell therefore adopts an empiricist ‘urgency and need for directness about the truth of the world around him’ which is seen most readily in his ‘plain, transparent and simple literary style’ that merely skims the surface appearance of social relations (Wilkin 2012: 202; see also Norris 1984; Williams 1981). This article has argued to the contrary that Orwell in fact presents a more critical, sophisticated and less conservative exploration of culture and society. As Rae (1999) similarly notes one of Orwell’s aims is indeed to penetrate ‘surface-truths to uncover the 31 grim realities hidden beneath’ (Rae 1999: 85). Appearances might suggest for example that British society is one in which workers simply accept their lot in life. Beyond these appearances, observes Orwell, lies a deeper reality, one where the exterior of what seems to be an acceptance of their lot by workers is entwined with the deeper reality of having to endure hard undesirable work. This more critical approach is also noticeable in his work on culture. Orwell appreciates that the surface appearances of popular culture are also bound up with a deeper reality which includes his own everyday experiences (see also Roberts 2010). Orwell wants to convey to his readers how popular emotional experiences operate at different societal levels, which also impact on his own experiences and perceptions of the world. Orwell therefore wishes to create a circle of meaning between himself and his readers by turning his own political and social writing into an ‘art form’ (Orwell 1981: 753). He does this in part by speaking about the world through his own contradictory and dialogical embodiment. Orwell does not claim to speak for others, but claims, instead, to speak from his own embodied experience within which he momentarily experiences the embodied experience of others. Orwell not only therefore explores themes in cultural studies that have since become established parts of the discipline’s canon he also shows how cultural and social commentators might transform their own embodied experiences into matters of public concern. Bibliography 32 Bakhtin, M.M. (1981) The Dialogic Imagination, ed. by M. Holquist, trans. by C. Emerson and M. Holquist, Austin: University of Texas Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1984a) The Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, ed. and trans. by C. Emerson, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1984b) Rabelais and His World, trans. by H. Iswolsky, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1986) Speech Genres and Other Late Essays, trans. by V. W. McGee, ed. by C.Emerson and M. Holquist, Austin: University of Texas. Barker, C. (2008) Cultural Studies, third edition, London: Sage. Bottero, W. (2004) ‘Class Identity and the Identity of Class’, Sociology 38(5): 985-1003. Bounds, P. (2009) Orwell and Marxism, London: I.B. Tauris. Bourdieu, P. (1984) Distinction, London: Routledge. Bourdieu, P. and Wacquant, L. (1992) An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Clarke, B. (2007) Orwell in Context, London: Palgrave. Coleman, J. (1972) ‘The Critic of Popular Culture’ in M. Gross (ed.) The World of George Orwell, London: Weidenfield and Nicolson. Cook, D. J. (1982) ‘Marx’s Critique of Philosophical Language’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 42(4): 530-554. Deleuze, G. (1994) Difference and Repetition, trans. P. Patton, London: Althone. Deleuze, G. (2005) Cinema 1: The Movement Image, trans. H. Tomlinson and B. Habberjam, London: Continuum. Deleuze, G. and Félix G. (1984) Anti-Oedipus, trans. R. Hurley, M. Seem and H. R. 33 Lane, London: Athlone Press. Deleuze, G. and Félix G. (1988) A Thousand Plateaus, trans. B. Massumi, London: Althone Press. Dowling, R. (2009) ‘Geographies of Identity: Landscapes of Class’, Progress in Human Geography 33(6): 833-839. During, S. (2005) Cultural Studies: A Critical Introduction, London: Routledge. Edensor, T. and Millington, S. (2009) ‘Illuminations, Class Identities and the Contested Landscapes of Christmas’, Sociology 43(1): 103-121. Erikson, R. and Goldthorpe, J. (1993) The Constant Flux, New York: Oxford University Press. Fiske, J. (1989) Understanding Popular Culture, London: Unwin Hyman. Fiske, J. (1993) Power Plays, Power Works, London: Verso. Fowler, R. (1995) The Language of George Orwell, London: Palgrave. Grossberg, L. (1992) We Gotta Get Out of this Place, London: Routledge. Hall, S. (2006) ‘Encoding/Decoding’ in M. G. Durham and D. M. Kellner (eds), Media and Cultural Studies: Keyworks, revised edition, Oxford: Blackwell. Hartley, J. (2003) A Short History of Cultural Studies, London: Sage. Hebson, G. (2009) ‘Renewing Class Analysis in Studies of the Workplace: A Comparison of Working-class and Middle-class Women’s Aspirations and Identities’, Sociology 43(1): 27-44. Hodge, B. and Fowler, R. (1979) ‘Orwellian Linguistics’ in R. Fowler, B. Hodge, G. Kress and T. Trew (eds), Language and Control, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 34 Hoggart, R. (1971) The Uses of Literacy, London: Chatto and Windus. Lewis, J. (2002) Cultural Studies: The Basics, London: Sage. Marx, K. and Engels, F. (1998) The German Ideology, New York: Prometheus Books. McGuigan, J. (1992) Cultural Populism, London: Routledge. Newsinger, J. (2001) Orwell’s Politics, London: Palgrave. Norris, C. (1984) ‘Language, Truth and Ideology: Orwell and the Post-War Left’ in C. Norris (ed.), Inside the Myth: Orwell: Views from the Left, London: Lawrence and Wishart. McRobbie, A. (1991) Feminism and Youth Culture, London: Macmillan. Orwell, G. (1970a) The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters, Vol. 2, ed. S. Orwell and I. Angus, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1970b) The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters, Vol. 3, ed. S. Orwell and I. Angus, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1981) George Orwell: Complete and Unabridged, London: Book Club Associates. Orwell, G. (1983) The Penguin Complete Novels of George Orwell, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1984) The Penguin Essays of George Orwell, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1989a) Homage to Catalonia, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1989b) The Road to Wigan Pier, London: Penguin. Orwell, G. (1989c) Down and Out in Paris and London, London: Penguin. Johnson, L. (1979) The Cultural Critics, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Rae, P. (1999) ‘Orwell’s Heart of Darkness: The Road to Wigan Pier as Modernist Anthropology’, Prose Studies 22(2): 71-102. 35 Roberts, J. M. (2010) ‘Reading Orwell through Deleuze’, Deleuze Studies 4(3): 356-380. Rojek, C. (2007) Cultural Studies, Cambridge: Polity. Thompson, E. P. (1974) ‘Inside Which Whale?’ in R. Williams (ed.), George Orwell: A Collection of Critical Essays, London: Prentice Hall. Savage, M. (2000) Class Analysis and Social Transformation, Open University Press. Skeggs, B. (2003) Class, Self, Culture, London: Routledge. Storey, J. (2012) Cultural Theory and Popular Culture, sixth edition, Harlow, Essex: Pearson. Strinati, D. (2004) An Introduction to Theories of Popular Culture, second edition, London: Routledge. Street, J. (1997) Politics and Popular Culture, Cambridge: Polity Press. Turner, G. (1990) British Cultural Studies, London: Routledge. Tyner, J. A. (2004) ‘Self and Space, Resistance and Discipline: A Foucauldian Reading of George Orwell’s 1984’, Social and Cultural Geography 5(1): 129-149. Voloshinov, V. N. (1973) Marxism and the Philosophy of Language, translated by L. Matejka and I.R. Titunik, London: Seminar Press. Watt, P. (2009) ‘Living in an Oasis: Middle-Class Disaffiliation and Selective Belonging in an English Suburb’, Environment and Planning A 41: 2874-2892. Wilkin, P. (2010) Tory Anarchism: A Very Peculiar Practice, London: Libri Publishing. Wilkin, P. (2012) ‘George Orwell: The English Dissident as Tory Anarchist’, Political Studies 61(9): 197-214. Williams, R. (1971) Orwell, London: Fontana Modern Masters. Williams, R. (1981) Politics and Letters, London: Verso. 36 Williams, R. (1983) Culture and Society 1780-1950, New York: Columbia University Press. 1 There’s an echo in these criticisms of E. P. Thompson’s accusation that Orwell constantly snipes at the radical Left (Thompson 1974: 84-6). Coleman (1972) does take Orwell’s writings on popular culture seriously, but his original paper was published before the advent of contemporary studies of popular culture. 2 37