ESPGHAN/ESPID Guidelines for the Management of AGE in

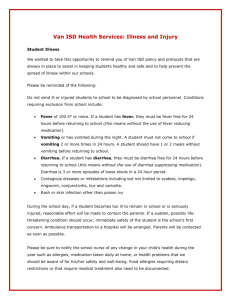

advertisement