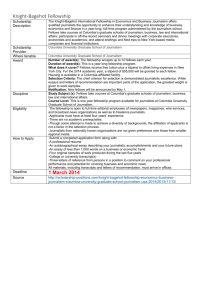

2014 World Press Institute Fellowship Final Report

advertisement

US Studies Centre – WPI final report Shalailah Medhora The World Press Institute Fellowship gives a group of mid-career journalists the chance to visit iconic, well-regarded and successful media outlets while immersing themselves in the American culture and way of life. This year, I was chosen as one of nine journalists from around the world to undertake this inspiring program. Eight other countries had representatives, apart from Australia: Bulgaria, Denmark, India, The Netherlands, Pakistan, Russia, South Africa and Venezuela. The other participants were journalists, editors, reporters and producers. We visited nearly a dozen different cities and towns and the names listed in chronological order at the bottom of this report. The Fellowship took place between August and October, after I had resigned from my role as a producer/reporter at SBS TV News, and before I’d started my new role as a political reporter at The Guardian. I filed stories for The Guardian based on news gathered while on the Fellowship. The links to those articles are scattered through this report. My particular area of interest, and the main reason I applied for the Fellowship in the first place, was to try and understand how the American industry is adapting to the changing media landscape. 2014 has been a year of great turmoil in the domestic and international media industries. The harbingers of doom have been wringing their hands, surmising that the digital revolution means the end of traditional media as we know it, and to an extent they are right. Social media has further entrenched its influence in news making and news gathering. In-depth investigative pieces in mainstream media are being passed over in favour of more cost-effective short reads that can be syndicated and replayed or reused. Public broadcasters are fighting for funding, trying to convince financiallystretched governments that their existence is vital for the functioning of democracy. Journalists around the world are losing their jobs, particularly in foreign bureaux, as the appetite for costly international news wanes. Given the challenges, it’s easy to understand why journalists, editors, producers, presenters and reporters are deeply concerned about what the future will bring for them and for the industry to which they’ve dedicated their lives. I undertook the WPI Fellowship with these issues in mind, looking at this tumultuous time in the industry as an opportunity for growth and diversification, rather than as the slow, spluttering end of an era. I tried to see how each of the organisations we visited was navigating the choppy waters of change, eager to apply this to my own professional life. Established media One of the greatest parts of this program was that we Fellows had phenomenal access to senior editors at large, well-established media organizations. All were 1 incredibly generous with their time and patient with our seemingly unending questions. Bashful WPI fellows meet pre-eminent NYT opinion writer, Thomas Friedman. Our first real taste of this was in Washington DC, when we visited James Fallows from Atlantic Monthly, Thomas Friedman from the New York Times, as well as editorial staff at The Washington Post and Wall Street Journal. Later in the trip we visited the NY Times headquarters, CNN, The Guardian and The Miami Herald. By and large, America’s most popular newspapers, radio stations and television networks have been the slowest to adapt to the changing media landscape. Some, because of the mistaken belief that their reputation and standing will keep them on top; others because change is slow and difficult to implement. But they ignore the digital revolution at their peril. That’s a conclusion that Spanish-language broadcaster Univision arrived at only recently. Univision is one of the most-viewed news networks in the US. It has the Hispanic TV market cornered, and because of this, saw no reason to change its business model. But, as American demographics changed, it realised that it had to change too. Borja Echevarria, the deputy digital news director at Univision, said eliciting change in the organisation was difficult as older television journalists bucked against producing stories for online audiences. “Audiences change before the business models. Always. Just looking at our kids, we know what is going to happen. Kids want the news online and right away,” Echevarria said. “Big media companies are slow and to move then takes a lot of time, so you have to start moving before its too late.” 2 On the other hand, the Fellows visited a number of smaller and newer companies and news outlets that were much more adaptable to change. For example, I was very interested in the way both The Texas Tribune in Austin, and MinnPost in Minnesota use and incorporate data journalism credibly under their mastheads. The Texas Tribune has a mini website on how much politicians and public officials are being paid. The data lets users to explore and compare salaries, and is taken entirely from public records. The MinnPost has a section that auto-updates crime figures by location, using data from Minnesota’s police department. These innovative uses of technology allow and encourage interactivity, and recognise that staid, traditional forms of storytelling are not always the most suitable in the modern media landscape. I was also impressed with the way Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) integrated multimedia journalism into the way it presented its biggest scoop ever. MPR was given documents detailing the cover-up of sex abuse in the state’s Catholic church system. The documents led to a months-long investigation that unearthed even more allegations. The radio station decided to make online part of the roll out of its coverage on the issue, and kept a database of the whereabouts of the priests and officials accused of abuse. Likewise, we saw the hugely popular Politico make the decision not to print a hardcopy outside of Washington DC, citing the cost and coverage benefits of an online-only publication. Politico poured its scant early resources into building an intuitive website and hiring political journalists whose focus would be to break news stories. The American version of The Guardian made the same decision, believing that there was no real benefit in printing a hardcopy. 3 The capability for smaller companies to innovate should not be underestimated. While mainstream media rests on its laurels, smaller outlets are catching up in ratings, and more importantly, capturing new audiences. That’s not to say that larger, better-established news outlets are ignoring the multimedia space all together. Indeed, when the Fellows visited the NY Times headquarters, we sat in on the morning editorial meeting. The purpose was to nut out the layout of the following day’s newspaper, including the front page. But more time was spent on determining the layout of the website. The editors there realized that much of the paper’s audience read the online site regularly. Some are ex-pats who don’t have access to hardcopy versions of the paper; others simply log in for the most updated version of a story throughout the day. They were still trying to work out the best way to monetise these eager eyeballs, but they recognized the vital importance of having an online presence. Newsroom trends There were two seemingly divergent and opposing trends emerging in the newsrooms we visited. On the one hand, journalists are choosing or being forced to choose to diversify their skills to fit a new multimedia model. Radio journalists at MPR were learning how to write for online and use content management systems to post their articles onto the station’s website. So too were CNN correspondents. Journalists at the Texas Tribune would lead panel discussions at community fundraising events and others would engage in public relations exercises. 4 But at the same time, news organizations were shrinking their operations, closing foreign bureaux and taking syndicated material that was cheaper and easier to reproduce. A few industrious news outlets that we visited decided to cash in on this as best they could, by selling content or giving it away for free for the exposure. Philanthropic news outlets are the most likely to try this method, with both ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting producing investigative pieces for dual-publication on other sites. New sources themselves are seeing the value of providing scoops for a number of outlets. For example, Edward Snowden offered his astounding cache of siphoned documents to journalists from both The Guardian and The Washington Post, prompting competition, but also forcing the outlets to work together. Though the American media industry is evolving and adapting, as outlined above, in some ways it is still behind the Australian industry. Given the size of the US news industry, the inevitability of multi-skilling is still a way off. Unlike in Australia, news outlets in the US can survive financially by finding their niches and doing what they do best. The US population can sustain this trajectory for sometime to come, though it’s certainly not a successful long-term business model. I was surprised at how few TV, print and radio journalists in America provided online content for their own stories. The Australian media industry is small and has serious problems with revenue, ownership and political influence, but it is miles ahead of the American system when it comes to multi-skilling its journalists. Australian journalists know that if we don’t keep up with the times, we’ll be redundant. Necessity teaches us to adapt. I saw little of this in America, despite companies’ attempts to move in that direction. Philanthropic outlets Many of the news outlets we visited were solely funded by philanthropic grants and donations. Some, like the MinnPost, are majority-funded from its own readership; a dedicated audience that values having a local voice and is willing to open their wallets to secure its existence. Others, like the Center for Investigative Reporting, are funded by large corporate or philanthropic donations, with seemingly little interference from sponsors in the day-to-day editorial decisions. While Australia has community radio stations that run entirely on money gathered from listeners, there are very few philanthropic-run news outlets of note here. Having spent several years working in community radio, I understand first-hand how difficult it is to get Aussie news consumers to part with their money. I think that’s largely because Australians feel like they are already paying for broadcasters with their tax dollars. Their hard-earned cash is going to producing high quality journalism already, so why shell out for more? The American philanthropic model is a unique one. I noticed that Americans really feel a sense of personal responsibility in funding the arts, charity and yes, even media. Its government funded media outlets are, with a few exceptions, small and not very popular. So the onus is on the listener/viewer/reader to keep paying for a product that they love. And they do – in their millions. 5 Particularly noteworthy is the rise of hyper-local philanthropic news outlets like MinnPost. Sensing a gap in the market for high-quality local news, these organisations sprung up from humble beginnings to quickly become fixtures in their communities. The Texas Tribune began in the same way, but soon took in state-wide politics and news. The fact that these organisations have thrived in a competitive news environment is testament to the strength of the philanthropic model in American society. Posing before heading up Chicago’s Willis Tower. American society Around the world America is a sheriff, an ally, an antagonist or an enemy. But for 316 million who call themselves American, the US is simply home. We were incredibly privileged to be exposed to several different communities and ways of life within the US. We interacted with diverse and engaging people around the country – from Minnesotan farmers and Brooklyn schoolteachers, to Federal Court judges and Harvard alumni. These people helped mould our image of Americans as generous, pluralistic, engaging people. The two themes of this year’s WPI Fellowship – global health and surveillance and data privacy – opened us up to meeting a range of interesting people with passions quite different from our own. In Washington, we had an eye-opening off the record chat with former deputy head of the National Security Agency, Chris Ingles, who shared with us why data gathering was vital to western governments. That argument was countered by Snowden’s New York-based lawyer Ben Wizner. He put forward his case as to why widespread surveillance was detrimental to civil liberties. I asked Wizner what he thought about 6 the Australia data retention proposal, and his answer formed the basis of an article I wrote later for The Guardian, which ran on both Australian and international versions of the site. The Fellows and I met with several tech experts in Silicon Valley, from Berkley, Symantec and the Electronic Frontiers Foundation, all of whom had insights and different perspectives on data retention. The subject of global health was very timely, as our visit coincided with the first case of Ebola being detected in the US. We had visited the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just days before the case was confirmed, where we had a thorough conversation with some of world’s best immunologists and Ebola specialists. I was able to write another article for the Guardian’s global website from the information received from the health agency. The Fellowship also provided an important reminder of the underreported but deadly diseases affecting the world. Talking to NGOs like the Gates Foundation in Seattle, the Carter Center in Atlanta and the McArthur Foundation in Chicago, alerted us to the work that these organizations do behind the scenes to stamp out diseases that don’t have the same level of public interest as Ebola. Walking into the mosquito room at Seattle Biomedical Research Center, where they study malaria-carrying vectors, was a particularly unique experience. While I found it fascinating, I won’t necessarily be volunteering to do it again. The value of journalists One of the most surprising elements of the trip for me was just how much I learnt about the people who make up my profession. I never realised before just how much of a “breed” journalists are. Personality-wise, the nine of us Fellows are all extremely different. But we are observant to our surroundings, curious, expressive and intrepid. We share a love of storytelling and of language and communication. We saw these qualities over and over again in the successful journalists we were honoured to meet during this Fellowship. The Atlantic Monthly’s James Fallows was candid about his struggles in adapting to online news. The Star Tribune’s investigative reporter Paul McEnroe moved us to tears in sharing his stories of covering the first Gulf War. Three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Thomas Friedman took us through his creative process, shooing away his secretary who had come to rescue him from a group of wide-eyed Fellows. And warm-hearted WPI alumni Bruno Lopez won us over with a table of Peruvian food and tales of what the Fellowship was like in the old days. I was humbled by what some of the other Fellows on the trip with me have to go through when reporting stories, and I was inspired by their courage and their dedication. They taught me a great deal and reminded me why I wanted to become a journalist in the first place. Being able to reignite my passion for my career is the greatest gift the Fellowship gave me. The best thing the media industry has going for it is its people. The ability of an organisation to adapt to change is entirely dependent on its workforce. It is young journalists, by and large, who are looking at the way their audience is evolving and seeking out the skills to be able to evolve along with them. Journalists love social media. We’re prolific on Twitter and don’t shy away from using Facebook to help us secure sources. Young journalists like myself are at the forefront of change, and we’re not baulking from the immense challenges faced by the industry. 7 So, yes, it’s a deeply challenging time for the media industry. Job losses will continue. The tussle between long and short reads will intensify. The number of international bureaux will shrink. But as long as there are journalists, the industry will survive. I’m quite sure of that. Not the set of ‘Friends’. I want to thank David McDonald, Doug Stone and the rest of the World Press Institute, as well as Nina Fudala, Bates Gill and the wonderful team at the US Studies Centre for giving me this once-in-a-lifetime chance to take stock and observe my own industry, while simultaneously discovering a whole new country. These opportunities seldom arise, and I feel privileged to have experienced it. They say that sailors have a lover in every port. I think WPI Fellows have a friend in every port. I’m proud to have been part of the Class of 2014, and of the wider WPI family. Links to blog posts During the Fellowship, I filed blogs for the WPI website. A compile of the blogs can be found here: http://worldpressinstitute.org/wpi-reports/blogs/shalailah-medhora I also filed for the US Studies Centre. Links to the blogs can be found here: http://ussc.edu.au/blogs/people/shalailah-medhora 8 WPI 2014 schedule Minneapolis/St Paul Ely, Minnesota Tracy, Minnesota Washington DC New York Miami Atlanta Austin San Francisco Seattle Chicago Minneapolis/St Paul 9