File - Austin Stutts

advertisement

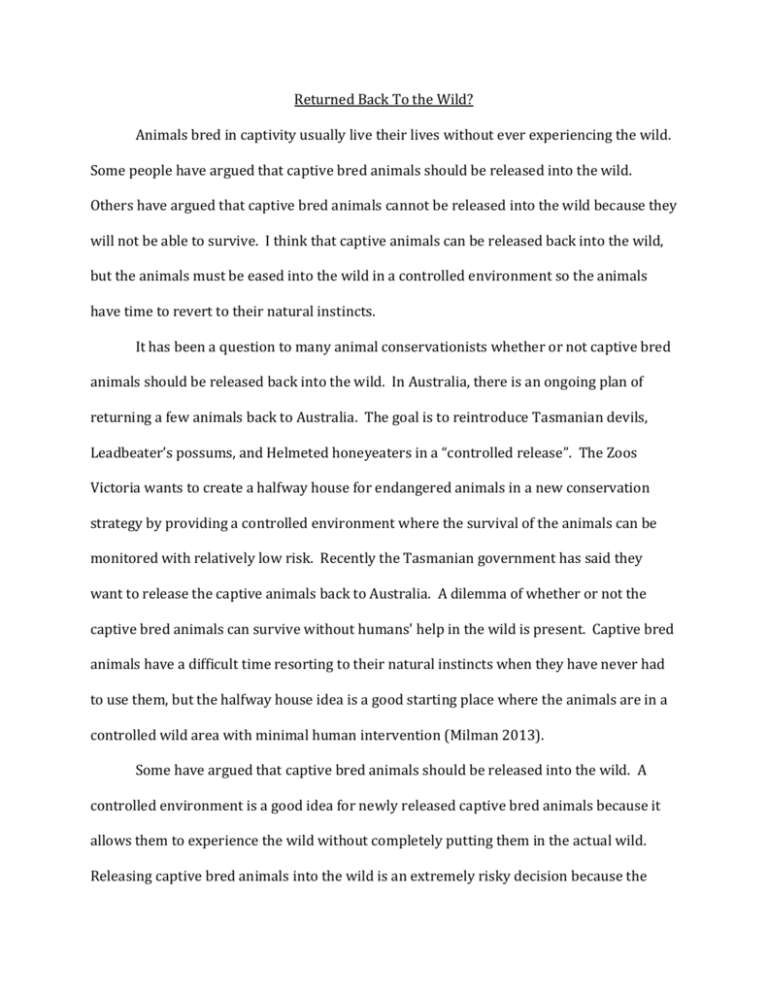

Returned Back To the Wild? Animals bred in captivity usually live their lives without ever experiencing the wild. Some people have argued that captive bred animals should be released into the wild. Others have argued that captive bred animals cannot be released into the wild because they will not be able to survive. I think that captive animals can be released back into the wild, but the animals must be eased into the wild in a controlled environment so the animals have time to revert to their natural instincts. It has been a question to many animal conservationists whether or not captive bred animals should be released back into the wild. In Australia, there is an ongoing plan of returning a few animals back to Australia. The goal is to reintroduce Tasmanian devils, Leadbeater’s possums, and Helmeted honeyeaters in a “controlled release”. The Zoos Victoria wants to create a halfway house for endangered animals in a new conservation strategy by providing a controlled environment where the survival of the animals can be monitored with relatively low risk. Recently the Tasmanian government has said they want to release the captive animals back to Australia. A dilemma of whether or not the captive bred animals can survive without humans' help in the wild is present. Captive bred animals have a difficult time resorting to their natural instincts when they have never had to use them, but the halfway house idea is a good starting place where the animals are in a controlled wild area with minimal human intervention (Milman 2013). Some have argued that captive bred animals should be released into the wild. A controlled environment is a good idea for newly released captive bred animals because it allows them to experience the wild without completely putting them in the actual wild. Releasing captive bred animals into the wild is an extremely risky decision because the animals has never had to fend for themselves in the wild and always had humans to provide for them. Captive bred animals are usually used to reinforcement programs for food and are generally less likely to survive than wild conspecifics. These reinforcement programs usually consist of being fed by humans in exchange for their good behavior in captivity. The good behavior is when the animals decides not to follow their natural instincts on what to eat and how to act. However the halfway house idea is a good start to how to go about releasing captive bred animals back into the wild. The idea allows the captive animals to start providing their own food and protection from their predators in an enclosed wild area, all the while humans can monitor how well they are surviving and provide assistance when needed. The question of whether or not captive bred animals should be released needs to be researched and more data need to be collected to make the correct decision. Further support of releasing captive bred animals can be seen shown by Mitchell’s (2011) research. Mitchell (2011) states that more captive bred burrowing owls survived being released into the wild with a soft-release rather than a hard release. The soft release consisted of releasing the owls in pairs, and providing above ground enclosures for shelter at first. This approach yielded better survival rates rather than a hard-release where the owls are given nothing. Some have argued that captive bred animals should not be released into the wild because they are not capable of surviving by themselves without humans’ support as well as the wild animals can. There have been several studies of how well captive bred animals have faired after being released into the wild, and generally the result is that survival is lower for captive bred animals released into the wild than the same animals that is wild born. Champagon (2012) studied the survival of captive bred Mallards being released into the wild and found a change in Mallard physiology and behaviors. The study included three groups: control captive bred Mallards, captive bred Mallards that were released into the wild, and wild Mallards. After a year of being released the gizzard weights were lower in the control Mallard group and the released Mallards showed more preference than the wild Mallards to eat anthropogenic foods. This resulted in a lower survival for the released Mallards when food provisioning was not available during harsh winter conditions. The released Mallards were not able to change their lifestyles to survive as well as the wild Mallards (Champagon 2012). With the research that has already been completed on the survival of released captive bred animals, the data indicate that it is not a good idea to release them straight into the wild. The captive bred animals are too accustomed to human assistance and are unable to provide their own food or protection from predators. Most of the released animals preferred to eat food that was produced by humans or humans’ food byproducts, which leads to a significant decrease in their ability to survive because they are dependent on humans. However the halfway house idea could produce some better results because the animals are being placed in an environment that could allow the animals to become independent of humans. Work Cited Champagon, J., M. Guillemain, J. Elmberg, G. Massez, F. Cavallo and M. Gauthier-Clerc. 2012. Low survival after release into the wild: assessing “the burden of captivity” on Mallard physiology and behaviour. European Journal of Wildlife Research 58: 255267. Milman, O. 2013. Tasmanian devils to be released back on to main land. Online: Http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/aug/23/tasmanian-devilsrelease-onto-mainland. Accessed September 2013. Mitchell, A.M., T.I. Wellicome, D. Brodie, and K.M. Cheng. 2011. Captive-reared burrowing owls show higher site-affinity, survival, and reproductive performance when reintroduced using a soft-release. Biological Conservation 144: 1382-1391.