here

advertisement

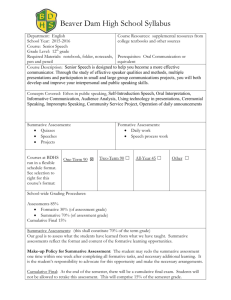

Summary provided by Robert Pulvermacher III in NIU’s Office of Assessment Types of Assessment Formative. Formative assessments are on-going assessments, reviews, and observations in a classroom. Teachers use formative assessment to improve instructional methods and student feedback through teaching and learning processes (William & Black, 1996). One way of conceptualizing formative assessments are as “practice.” Students are not held accountable in terms of grades with formative assessment, but rather receive information about their learning progress as a means to self-assess their level of understanding. Examples of formative assessment include criteria and goal setting, observations, questioning strategies, self and peer assessment, and student record keeping (Garrison & Ehringhuas, 2007). Practical examples include asking students to submit one or two sentences identifying the main point of a lecture, having students submit an outline for a paper, and early course evaluations (Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence, 2012). Formative assessment is dependent on student involvement. Students must be involved as both assessors of their own and other student’s learning. Teachers act as participants in the learning process via identifying learning goals, setting clear criteria for success, and designing assessment tasks (Garrison & Ehrnhaus, 2007). Summative. Summative assessments are given to assess what students do and do not know about a particular learning topic. They measure the level of success or proficiency that has been obtained at the end of an instructional unit. Examples include final exams, state assessments, end-of-unit chapter tests, and benchmark assessments. Summative assessments are vital to gauging students understanding of learning topics, but because they happen after the learning process, are less useful in providing information at the classroom level to make instructional adjustments and interventions. In short, formative assessments tell “where we are now,” while summative assessments tell “how well the course went.” Course-Embedded Techniques Course-Embedded Assessment involves the assessment of the actual work produced by students in our courses. Student work in used to measure the achievement of course learning objectives. Assessments are conducted not to grade (or further grade) the student but to assess the learning outcomes of the course. Course-Embedded Assessment can have a variety of advantages, including purposeful reexamination of course objectives, sequencing, and content and feedback that allows instructors to redesign assignments and give clearer direction to students about what is expected. Course-Embedded Techniques Applied to Formative and Summative Assessment Course-embedded assessments may be formative as well as summative. They can be used to evaluate the development of student skills and provide feedback (formative) and they can be summative as well (evaluating final student product (MSU.edu, 2012)). For example, one could use the sentences that students wrote to sum up a lecture (formative) or a final graded essay (summative) as units of a course-embedded assessment. References Ayala, C., & Shavelson, R. From Formal Embedded Assessments to Reflective Lessons: The Development of Formative Assessment Suites. Applied Measurement in Education, 21(4), 315-334. Colwell, J. L., Whittington, J., & Higley, J. B. (2004). Tools for Using Course-Embedded Assessment to Validate Program Outcomes and Course Objectives. In asee.org. Retrieved July 30, 2012 Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence. (n.d.). Formative vs Summative Assessment. In cmu.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2012 Garrison, C., & Ehringhaus, M. (2007). Formative and Summative Assessments in the Classroom. In amle.org. Retrieved July 30, 2012 Missouri State University Assessment. (n.d.). Chapter 2: Couse-Embedded Assessment. In missouristate.edu. Retrieved July 30, 2012 William, D., & Black, P. (1996). Meanings and Consequences: a basis for distinguishing formative and summative functions of assessment? British Educational Research Journal, 22(5), 537-548.