Open

advertisement

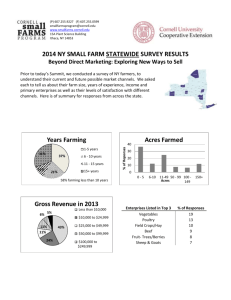

ANCWG/2015/009 ANC 2018 – PROJECT 4 - SUSTAINABLE FARMING SYSTEMS – UPDATE The aims of the project are to: 1. Define sustainable farming systems and describe spatial distribution of farming systems in Scotland. 2. Investigate questions around required levels of support for business viability. This needs to account for the economics of maintaining a viable enterprise on different land qualities under different farming systems (note: this analysis will focus on future need not past payment levels) 3. The importance of LFASS to farm business and farm household incomes could also be reviewed. Initial Findings There are several options for using existing typologies to define farming systems in Scotland: Census farm types; Farm Accounts Survey types; QMS enterprise types; Farm Management Handbook enterprise types; High Nature Value Farming; Crofting; Or a custom definition based on land mix. Research on Economic Sustainability: o Rising land values have seen the average net worth of Scotland’s farming double over the last seven years and the same pattern is reflected across farm types. o LFA farm types have the lowest levels of wealth, particularly specialist sheep farms o Comparing farm business incomes per FTE to the minimum wage identifies between 10 and 20 per cent of the industry are both short and long term non-viable. Non-viability is driven by lower size, the farm being a tenancy (rather than owned), upland based operations, and having high nature value farming status. o High and increasing asset values can help to explain why some farms that seem unviable on income measures are able to continue farming. o LFA farm types are almost exclusively dependent on subsidy for income. In relative terms LFASS is more important to farms in the Na h-Eileanan An Lar, Shetland Highland and Argyll and Bute regions. Research on Environmental Sustainability: o Several reports document the large decline in livestock numbers since decoupling, a report by SNH found the numbers and distribution of wild deer influence the extent to which livestock changes impact natural heritage. Anecdotal evidence and case studies suggest declines in livestock have negatively impacted natural heritage. o Evaluations of LFASS have identified both positive and negative environmental impacts. Research on Social Sustainability: o LFASS was found to safeguard jobs where it encouraged active land management o However, population decline in remote rural areas has a long and complex history so directly attributing changes to hill farming and livestock decline is difficult. 1 ANCWG/2015/009 Introduction This paper gives an overview of research on sustainable farming systems, covering: 1. Background 2. Defining Sustainable Farming Systems 3. Evidence on Sustainable Farming Systems in Scotland’s Less Favoured Area 3.1 Economic 3.2 Environmental 3.3 Social The evidence presented in this report covers the current economic, social and environmental situation in the Less Favoured Area. Work commissioned under the other projects will examine future distributions of payments. 1. Background The rationale for payments to ANCs is presented in the European Commission measure fiche: Payments in mountain areas or in other areas facing natural or other specific constraints (ANCs) aim at compensating farmers in total or partially for disadvantages to which the agricultural production is exposed due to natural or other specific constraints in their area of activity. Such compensation shall allow farmers to continue agricultural land management in order to prevent land abandonment as a precondition for maintaining the countryside and sustainable farming systems in the areas concerned.1 2. Defining Sustainable Farming Systems The term ‘sustainable farming systems’ can mean different things to different people. By definition, ‘sustainable’ means something can be maintained over time. The term invites linkage to the three dimensions of sustainable development: Environmental sustainability- natural capital is maintained or enhanced, for example soil and water resources are in good condition so future generations can continue to benefit from their use. Economic sustainability requires satisfactory returns to land, labour and capital in order to justify the continued use of these resources in farming. The EC rationale for ANC payments allows subsidies to supplement returns in cases where the agricultural production is limited by biophysical constraints. The temporal element of sustainability requires the physical capital stock is maintained over time (or substituted to other forms of productive capital). Social sustainability relates to maintaining the farm population, community or quality of life in farming. 1 Prior to the release of the new regulations debate in Scotland focused on the concept of vulnerable areas which are closely related to the sustainability issues related to biophysical constraints (Annex B has a brief summary) 2 ANCWG/2015/009 The European Commission measure fiche mentions “It is possible to have different levels of payments, expressing different degrees of constraints and different farming systems. The different levels of payments should be justified by calculations of income loss and additional costs.” The European Commission suggested we could use column 1 in the table in Annex 1 of Regulation 1242/2008 for a definition of farming systems. The categories are replicated in the table below for information. Table 1 - General Type of Farming 1. Specialist field crops 2. Specialist horticulture 3. Specialists permanent crops 4. Specialist grazing livestock 5. Specialist granivores 6. Mixed cropping 7. Mixed livestock holdings 8. Mixed crops – livestock 9. Non-classified holdings This classification does not give sufficient granularity to differentiate between farming systems in Scotland’s Area of Natural Constraint and we have had feedback from the Commission that we cannot use column 3 of Annex 1 of 1242/2008 which appears to rule out most useful definitions of farming systems in Scotland (definitions we had considered useful are included in the table below for reference). Table 2 - Scottish Farming Systems Description Categories Scottish farm Specialist Cereals; General Cropping; Specialist horticulture & permanent census categories crops; Specialist Pigs; Specialist Poultry; Specialist Dairy; LFA Cattle and Sheep; Non-LFA Cattle & Sheep; Mixed Holdings; General Cropping - Forage; Unclassified. Farm Accounts Specialist Sheep (LFA); Specialist Cattle (LFA); Other Cattle and Sheep Survey categories (LFA); Cereals; General Cropping; Dairy; Lowland Cattle and Sheep; Mixed. QMS Enterprise Cattle: LFA Hill Suckler; LFA Suckler; Lowground Suckler; Rearer finishers; Types Cattle Finishing; Cereal- Based Finishing; Forage-Based Finishing. Sheep: LFA Hill Ewes; LFA Upland Ewes; Lowground Breeding Flocks; Store Lamb Finishing. Farm Management There are around 75 crop/ livestock specific enterprise types. Beef Handbook enterprises include: Hill Suckler Cows; Enterprise Types Upland Suckler Cows; Lowground Suckler Cows. Sheep Enterprises include: Extensive Hill; Improved Hill; and various finishing types. High Nature Value Type 1 - high proportion of semi-natural vegetation Farming Type 2 - mosaic of low intensity agriculture and natural and structural elements (eg. walls, hedgerows) Type 3 – Supporting rare species Crofting Land designated as crofting land by the Crofting Commission. Use custom E.g. Hill Farming; Mixed Upland/ Hill Farming; Upland Farming, Non-ANC definition farming. Annex A presents maps of farm accounts survey types and of HNV farming systems. 3 ANCWG/2015/009 3. Sustainable Farming Systems in Scotland’s Less Favoured Area In the Scottish context there is a body of evidence covering issues related to the sustainability of farming and vulnerability in the Less Favoured Area. This paper does not seek to give a comprehensive account of this work but instead draws out relevant points from the key documents. This is organised under the three pillars of sustainable development: economic, environmental and social. 3.1 Economic This section examines three aspects of economic sustainability: the wealth of the sector; measures of income; and the importance of subsidy to income. 3.1.1 Wealth In the last seven years farmers have seen a doubling of average net worth driven largely by increases in land values. Figure 1 Large increases in net worth have occurred across all farm types but with farms predominant in lowland areas (cereals, dairy, mixed and cropping) seeing the biggest gains. The chart below shows that there are roughly three groupings, in 2013-14 average net worth: Cropping, Cereals, Dairy, Mixed average between £1.7m and £1.9m; Lowground Cattle & Sheep, Specialist Beef (LFA) and Other Cattle and Sheep (LFA) average around £1m and £1.1m Specialist sheep average just over £600k. 4 ANCWG/2015/009 Figure 2 Source: Farm Accounts Survey Unsurprisingly, there is variation by tenure with owner occupiers and mixed tenure farms seeing substantial increases in net wealth while tenanted farms have experienced more modest increases. Table 3 - Average Net Wealth by Tenure 2007-08 2013-14 Owner occupied £814,240 £1,643,100 Mixed tenure £719,598 £1,438,532 Tenanted £223,348 £291,568 Increase 102% 100% 31% Source: Farm Accounts Survey Owner occupied farms make up 68 per cent of Scotland’s farm businesses (with 66 per cent of the land), mixed tenure farms 8 per cent of businesses (with 20 per cent of the land) and tenanted 23 per cent of farm businesses (with 14 per cent of the land). High and increasing asset values set the context for examining farm incomes and can help explain why some farms that seem unviable on income measures are able to continue farming. 5 ANCWG/2015/009 3.1.2 Income Measures The Farm Accounts Survey (FAS) is based on a sample of approximately 480 farms and is the most reliable source of information on businesses profit and income (including subsidy payments and diversified income). In recent years, average incomes have fallen for Scotland’s farmers. Figure 3 Source: Farm Accounts Survey The chart below demonstrates the fluctuation in income experienced by farm businesses. The sectors with the biggest variability are general cropping and cereals where businesses are generally more dependent on market returns and less dependent on subsidy for income. Figure 4 Farm Business Income by Farm Type £90,000 £80,000 £70,000 £60,000 £50,000 £40,000 £30,000 £20,000 £10,000 £0 Specialist Sheep (LFA) Specialist Cattle (LFA) Cattle & Sheep (LFA) Cereals General Cropping 2013/14 2012/13 2011/12 2010/11 2009/10 2008/09 Dairy Lowland Cattle and Sheep Mixed Source: Farm Accounts Survey The Farm Accounts Survey team analysed farm business income per full time equivalent (FBI/FTE) for each farm type, comparing the results with the agricultural 6 ANCWG/2015/009 minimum wage. There are caveats given that not all farm businesses seek to maximise income but the analysis is still a useful indicator of the economic sustainability of the farm business in terms of the returns to labour. They found a much higher proportion of LFA sheep farms had an FBI/ FTE below the minimum agricultural wage than the Scottish average. Around two thirds of LFA specialist sheep farms have a farm business income per worker below the agricultural minimum wage (a quarter of LFA sheep farms had negative incomes). Specialist Cattle farms in the LFA were closer to the Scottish average with around a third with incomes per worker below the minimum agricultural wage and just under a fifth experiencing losses. Mixed cattle and sheep LFA holdings had a much lower proportion reporting negative incomes per worker but still saw around half of all businesses with an income per worker below the minimum agricultural wage. The limitation of this analysis is that it examines the sustainability of farm business income and not the farm household income. To add context, off-farm income, diversification margins and average net worth are provided alongside the wage analysis. These additional sources of wealth or income can be used to crosssubsidise agricultural production or to maintain household income where the farm business yields low returns. Table 4 Average net worth: Tenanted: £209k Owned: £884k Diversification Margin: £3,519 Average off farm income: £9,436 Average net worth: Tenanted: £365k Owned: £1,208k Diversification Margin: £1,079 Average off farm income: £9,559 Average net worth: Tenanted: £252k Owned: £1,538k Diversification Margin: £1,047 Average off farm income: £9,371 Source: Economic Report on Scottish Agriculture 2015 Edition. Income measures can also be used to consider business viability. SRUC developed an index of viability of farm incomes in Scottish agriculture based on the Farm Accounts Survey2. Viability was assessed as being able to generate an hourly cash income greater than the agricultural minimum wage in the short term (a given year) or the long term (over a three year moving average). The research found that: “In 2000, just over 40% of all farms in the sample were both short- and long-term viable, compared to over 60% in 2010. If a farm is both short- and long-term viable in one year, it has a high probability of remaining in that state for the next year. 2 http://www.sruc.ac.uk/downloads/file/1537/2013_assessing_farm-level_viability_in_scotland 7 ANCWG/2015/009 Figure 5 Source: SRUC This research shows a steady increase in the number of viable farms over time relative to the other classes. In addition, those farms which are both short and long term non-viable (STNV LTNV) have fluctuated between 20 to 10% of the total proportion of the industry. Those in non-viable states have a 50:50 chance of staying non-viable the next year. Non-viability is driven by lower size, the farm being a tenancy (rather than owned), upland based operations, and having higher nature value farming status”. The latest year of the analysis (2012/13) shows the sectors with the highest proportion of non-viable farms are Lowland Cattle and Sheep, LFA Specialist Sheep, and LFA Specialist Cattle. Cereals, General Cropping and Dairy farms have a very low proportion of non-viable businesses. On average, over the last three years: 29% of the sampled businesses in the LFA Specialist Sheep sector were unviable in the short or long term; compared to 22% for the LFA specialist beef sector; and 11% for (mixed) LFA cattle and sheep farms. This links to evidence shown in Section 3.1.3 below that shows LFA livestock sectors are most dependent on subsidy for their viability. The question of how to provide support to maintain viability is difficult because of the differences between the top and bottom performing businesses in each sector. Work has been commissioned to examine the effect of future pillar 1 payments on farm business incomes and viability. A report on “Alternative payment approaches for non-economic farming systems delivering environmental public goods”3 examined payment mechanisms to provide support for agri-environmental management and farming systems that deliver environmental public goods. Non-economic farming systems were defined as those “60% below the median farm business income over the years 2005 to 2008” and can be characterised as upland 3 http://www.snh.gov.uk/docs/A931062.pdf 8 ANCWG/2015/009 or hill farming operations dependent on livestock with low income, extensive systems that have high portions of rough or common grazing. These systems tend to coincide with high nature value farming areas. The report argues that for agri-environment payments income forgone and additional cost calculations are irrelevant where there are very low levels of profitability as they only perpetuate the problem of low profits. Indeed where farms are operating at a loss the authors argue: “There is therefore no income to forego and the economically realistic alternative is abandonment. Therefore the full cost of farming that land is an 'additional cost’ in itself”. The report tests three formulas that bring farm incomes to sustainable levels, with different treatment of the fixed and opportunity costs of farming. When tested, the formulas resulted in payments much higher than present agri-environmental and LFA support. Average payment per ha under the formulas: Table 5 The farm accounts survey on which the analysis above is based does not cover traditional crofting businesses. The report on the Economic Condition of Crofting 2011-20144 reviewed statistics on population, businesses, housing, labour, agricultural production, and surveyed crofters asking questions about incomes, business running costs and plans for the future. Crofting, as a social system, is designed to keep people on the land and sustain rural communities rather than provide a sole source of income for a family. Survey data outlined in the report and from the Schucksmith Report showed that crofts only provide a relatively small proportion of a crofter’s income, with most crofters receiving the majority of their income from non-crofting related sources. Crofting households spent an average of 11.7 hours per week on crofting-related activities over the last twelve months and received an average revenue of £4,900 for this work. The average business running cost was £3,900 (excluding any land and housing liabilities) meaning average income from on-croft activity as £1,000. Whilst agricultural activities represented the vast majority of crofting related output, businesses who have chosen to diversify receive a significant proportion of their income from other activities (B&B facilities were the most common form of diversification). For those households with at least one person engaged in non-crofting employment or self-employment, combined average earnings from these activities over the last twelve months was £27,500 from an average of 49 hours worked per week. 4 http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0047/00473575.pdf 9 ANCWG/2015/009 On the wider contribution of LFASS farming, the economic analysis in the “Less Favoured Area Support Scheme in Scotland: Review of the Evidence and Appraisal of Options for the Scheme Post 20105” report found agricultural sectors had strong linkages with animal feeds, manufacturing and other services sectors and the meat processing sector. LFA farm types were found to have output multipliers around 1.7 meaning £1 additional demand generates around £0.70 in the wider economy (this ranked between 9th and 11th of the 24 other sectors). 3.1.3 Importance of Subsidy to Farm Business Income The “Farm Business Income” (FBI) statistic is made up of the farm’s profit (or loss) plus subsidy payments (and diversified income)6. The FBI statistics show that many farm businesses in Scotland are dependent on subsidy payments for their long run survival. The commercial sector in Scotland is heavily reliant on subsidy payments to realise a profit. The chart below illustrates that on average over the last 5 years only 27 per cent of businesses in the Farm Accounts Survey sample have a positive farm business income in the absence of subsidy. Only 6 per cent make more than half their income from farming operations rather than subsidy. Figure 6 Source: Farm Accounts Survey This illustrates that a large proportion of the industry, even relatively health businesses, are dependent on subsidy payments for their business income. However, the chart above also illustrates that because subsidies support farm incomes, 93 per cent of businesses have a positive farm business income. There are clear differences across farm types in terms of dependence on subsidy support. 5 http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/171377/0047934.pdf 6 FBI can be considered the ‘return’ for the farmer and his/ her partners on their unpaid labour and capital invested in the farm. 10 ANCWG/2015/009 Figure 7 Source: Farm Accounts Survey LFA farm types are almost exclusively dependent on subsidy for their farm business income while farm types predominant in the lowlands (Dairy, General Cropping, Cereals, Mixed) see a much higher proportion of businesses able to make a profit in the absence of subsidy. The chart below shows livestock farms five year average FBI alongside the subsidy payments that contribute to FBI. For the three LFA farm types it is clear that on average businesses make a loss without subsidy (i.e. subsidy payments, which are included in FBI, are higher than total FBI). Figure 8 Table 6 - 5yr averages - subsidy as a % of FBI Specialist 146% Sheep (LFA) Specialist 152% Cattle (LFA) Cattle & 174% Sheep (LFA) Dairy 56% Single Farm Payment was, on average, the most important contributor to FBI. 11 ANCWG/2015/009 For farms receiving LFASS around 17 per cent are more reliant on LFASS than SFP. It is worth noting the variation across Scotland in terms of the importance of subsidy types by business. Figure 9 The figure below shows LFASS as a proportion of the main subsidies (SFP, LFASS and SBCS) paid to a region in 2013. Figure 10 12 ANCWG/2015/009 3.2 Environment The EC recommend that rural development policy should be used to preserve and develop HNV farming and forestry systems. HNV systems are characterised by semi-natural features, diversity of features and support species of conservation concern. HNV farming may be more likely to take place on certain types of land; in Scotland the majority of HNV farming activity tends to take place in LFA areas but there are also HNV farms on other land types. A typology of HNV Farming was developed with Type 1: Land with a high proportion of semi-natural vegetation. Type 2: Land with a mosaic of low intensity agriculture and natural and structural elements (field margins, hedgerows, stone walls, patches of woodland or scrub, small rivers etc). Type 3: Land supporting rare species or a high proportion of European or world populations Baseline indicators of HNV farming were generated for farming systems (e.g. sheep systems, beef cattle systems) using JAC and IACS data. A high proportion of rough grazing (>70%) and low stocking density (<0.5LU/ha) were used as an indicator of the semi-natural habitat likely to support HNV farming. The analysis was validated using Farmland Biodiversity Analysis (land cover OS mapping, species data, topographic data on field margins) and while this identified a larger area of HNV farming it was less suitable for annual EC reporting purposes. Based on the indicator the area estimated as being under HNV farming has ranged between 2.3 and 2.4 million hectares of agricultural land between 2009 and 2013. This equates to a range of between 41 per cent and 44 per cent of the UAA. Geographically, the Highlands made up the largest area of HNV farming in Scotland (43 per cent of HNV area being in Highland), followed by Argyll (11 per cent) and Tayside (10 per cent). The areas covered by mapping of potential area are much higher at approximately 4 million hectares (see map in Annex A). Appropriate levels of grazing are important to the environmental sustainability of the constrained area. ‘Retreat from the Hills’ 7 documented the dramatic decline in sheep numbers between 1999 and 2007, particular in the North West where some parishes experienced declines of between 35 and 60 per cent. Average numbers of sheep per unit declined over the period and to a lesser extent there were declines in the number of holdings with sheep. Cattle numbers also declined but not to the same extent and not in the same areas. Declines in livestock numbers accelerated after the introduction of the Single Farm Payment and decoupling of livestock numbers from payments. ‘Response from the Hills’8 updated the analysis to include the period between 2007 and 2010 characterised by rising beef and sheep prices, input inflation and 7 https://www.sruc.ac.uk/downloads/download/18/2008_farming_s_retreat_from_the_hills 8 http://www.sruc.ac.uk/downloads/file/57/response_from_the_hills_business_as_usual_or_a_turning_point 13 ANCWG/2015/009 favourable exchange rates. The report found more stability in regional suckler herds (with the exception of Angus and Lochaber with declines of 12 per cent and Borders with a decline of 6 per cent). In High Nature Value Farming areas in the North West the proportion of holdings with suckler cows increased. Trends in sheep numbers were reported to have continued on a downwards trend though the numbers of holdings with sheep stabilised with only a marginal decline over the period. The report highlighted the scale of change: “between 1997 and 2010 Dumfries and Galloway lost over 200,000 ewes (34.8% reduction), Lochaber, Skye & Lochalsh and Argyll and the Islands have 175,000 fewer ewes (37.1% reduction) and nearly half the ewes in the Western Isles have been removed”. The SNH report, “An Analysis of the Impact on the Natural Heritage of the Decline in Hill Farming in Scotland9” examined the impacts of the decline in the national cattle herd and sheep flock in hill farming areas in Scotland. The project related ‘on the ground’ changes in management and livestock numbers to impacts on natural heritage and rural communities. The report found that “Changes in the numbers and distribution of deer, and any future deer management, are key factors that will affect the extent to which future livestock declines impact on the natural heritage”. Three detailed case studies were also conducted (South Skye, West Borders and North Highlands). Between 1998 and 2008 ewe numbers per hectare of grazing land dropped from 1.41 to 1.11 in the West Borders, from 0.64 to 0.39 in South Skye and from 0.31 to 0.18 in North Highlands. The number of holdings with breeding ewes declined in all three areas and similar patterns were seen when examining the declines in the cattle herd. Qualitative and anecdotal evidence was compiled, with the main findings being the recognition of declining livestock numbers as a significant issue with negative social, economic and natural heritage impacts. The number of recognised natural heritage impacts was higher in South Skye and North Highlands. However, the report noted a lack of quantitative evidence on how livestock changes impacted on natural heritage. The environmental assessment in the “Less Favoured Area Support Scheme in Scotland: Review of the Evidence and Appraisal of Options for the Scheme Post 201010” found the scheme’s incentives to maintain livestock, a mix of cattle and sheep and to encourage good farming practice were environmentally positive but not necessarily targeted at priorities. In some intensive areas LFASS maintained employment but was linked to damaging stocking levels and input use. Findings from the “Ex Ante Evaluation of Scotland’s Rural Development Programme 2014-202011” on LFASS relate mostly to environmental impacts. A causal chain analysis identified positive and negative environmental impacts associated with LFASS. Where managed LFA land is maintained in lower intensity, mixed livestock grazing areas it is found to link to three potentially positive impacts: (1) retention and protection of diverse habitat mosaics; (2) Greater habitat opportunities for priority species; and (3) Reduced soil compaction and increased infiltration capacity reduces 9 http://www.snh.org.uk/pdfs/publications/commissioned_reports/454.pdf 10 http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/171377/0047934.pdf 11 http://www.gov.scot/Topics/farmingrural/SRDP/SRDP20142012/SRDP20142020ExAnteEvaluationSEA 14 ANCWG/2015/009 runoff at source. In extensive management low inputs or stocking densities had mixed impacts including reductions in soil erosion and preservation of organic matter but also some positive and some negative impacts on habitats supporting farmland birds. Intensive LFA land management with high inputs and stocking densities had the potential for grazing pressure to contribute to soil erosion, runoff and habitat degradation. The authors summarise findings as follows: “In summary, the LFASS causal chain analysis highlights the importance of balanced investment to ensure that Scotland’s LFA is kept in appropriate land management i.e. an appropriate balance of intensive versus extensive management. Where such a balance is struck, sustained investment in LFASS has the potential to contribute to a range of primarily beneficial environmental outcomes. In the absence of a new SRDP therefore, investment in an LFASS type scheme (e.g. through RDR Article 32 on payments to areas facing natural or other specific constraints) would not continue, posing a substantial risk of land abandonment in the LFA as hill farming becomes less tenable. In consequence, open grassland and moorland in the LFA would eventually follow a natural succession through scrub to woodland (below the tree line). This could be seen as potentially beneficial for biodiversity, but could also reduce the mosaic structure of the landscape which currently promotes biodiversity”. 3.3 Social The “Retreat from the Hills” report highlighted the uneconomic nature of hill farming which is reflected in negative net margins. With prices often below the cost of production, hill farming is often dependent on subsidy to continue. The report examined trends and Highlands and Islands saw the biggest reduction in full time occupiers and spouses. Availability of labour was also identified as an issue with declines in employees in many areas of Scotland. To investigate social sustainability a survey of LFASS recipients was issued as part of the “Less Favoured Area Support Scheme in Scotland: Review of the Evidence and Appraisal of Options for the Scheme Post 2010” project. This found that LFASS was relatively unimportant to household income (see table below). The Scottish Borders stood out as the region most dependent on LFASS for household income but this is perhaps partly a reflection of the Borders region receiving the highest payments at the time (according to the SRDP mid-term evaluation). Table 7 15 ANCWG/2015/009 The Economic Condition of Crofting report showed a mixed picture in terms of population change between 2010 and 2013 in crofting counties with Argyll and Bute, Eilian Siar, and North Ayrshire seeing small reductions in population while the remaining crofting counties saw increases in population. The report found that the adult age profile of crofting households is considerably older than the age profile of the crofting counties or Scotland as a whole. The SNH “Analysis of the Impact on the Natural Heritage of the Decline in Hill Farming in Scotland” project reviewed the literature on social impacts of the decline in livestock in the hills but found there was limited Scotland specific work and that population decline in remote rural areas has a long and complex history so directly attributing changes to hill farming decline is problematic. The mid-term evaluation of the SRDP 12included a section on LFASS. Economic benefits were judged to be dependent upon the continuation of active farming/ land management as it is these activities that stimulate the use of labour and capital that safeguards and creates jobs. The report estimated 9,650 net jobs were created/safeguarded and £365.1m net GVA was created/safeguarded per annum. The significant majority of farms (8090%) perceived LFASS helped improve efficiency, the quality of product produced, the value of outputs produced and to increased total outputs. In terms of jobs and social impacts the review found a small majority thought LFASS encouraged family members to stay on the farm, whilst almost three quarters of respondents thought the scheme made jobs more sustainable in the long run. Figure 11 Source: SRDP Mid-Term Evaluation 12 http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2011/03/21113609/44 16 ANCWG/2015/009 Annex A – Mapping of Scotland’s Farming Systems 17 ANCWG/2015/009 18 ANCWG/2015/009 Annex B – Vulnerable Areas Research Pack Inquiry The Inquiry recommendations for LFASS were intended to complement the approach taken to redistributing Pillar 1 payments (i.e. a combination of area payments, top ups and headage payments based around the LFA/ Non-LFA boundary) so cannot be seen as standalone recommendations for LFASS; it is however still worth summarising some of the relevant points. The Inquiry recommended that around two thirds of the LFASS budget should be transferred to Pillar 1 to increase top up payments in the LFA area with the remaining third of the budget to be directed to the areas at greatest risk of land abandonment to be defined as a vulnerable area. The next section details the work undertaken by the JHI to define a vulnerable area. Other points worth reciting, are the report’s acknowledgment of the enormous variation of the degree of disadvantage faced within the existing LFA area and that the Fragile and Very Fragile Areas deliver a disproportionate amount of public goods. There is also evidence to support the need for more detailed categorisation of farming systems than the Commission propose: “Given that the LFA is dominated by permanent grass and rough grazing where the only choices are which ruminant to use and how many, and given the well documented low profitability of farming in the LFA (in particular single suckled calf production), the outcome of a pure area based payment for this class of land is easy to predict. A simple area based payment system would decimate our productive upland and hill units. The risk of land abandonment with this class of land is high with the consequential loss of food production capacity, amenities and the negative impact on rural communities”. JHI Vulnerable Areas Report The Pack recommendation to define a vulnerable area including all of the current Very Fragile Area and some of the Fragile Area was taken forward by the James Hutton Institute. The criteria included socio-economic indicators (remoteness, transport costs, distance to markets etc); biophysical criteria based on the eight (low temperature, heat stress, soil drainage, soil texture and stoniness, soil rooting depth, soil chemical properties, soil moisture balance and slope) proposed by the EU to define Areas of Natural Constraint (ANC) and Land Capability for Agriculture (LCA). A satisfactory measurement of fragmented areas could not be developed and was dropped as a measure. The report concluded it was very challenging to produce a Vulnerable Area based on biophysical criteria and which has the relationship with the current fragility classification as described in the Pack Report. A Vulnerable Area defined by the inclusion of LCA classes 4-7 or 5-7 far exceeded the recommended by the Pack 19 ANCWG/2015/009 Report. It would include much of the current Standard Area as well as virtually all of the Fragile and Very fragile areas. As with the Rural Analysis Associates work the use of the socio-economic criteria of remoteness and transport costs would exclude this work being used to inform payment zones within the ANC scheme. Defining the Vulnerable Areas of Scotland, Rural Analysis Associates13 This report from 2011 argues that Vulnerable Farming Areas recommended by the Pack Inquiry should be based on use of both Article 18 ‘Mountain’ and Article 20 ‘Specific Handicaps’ designations. Under Article 18 the report recommends delimitation on the basis of slope, elevation, exposure (wind speed indicator) and/or more than 800m from a metalled road. The Article 20 area recommendation is being 2 hours’ drive time from a major town and with a high level of vulnerability judged against the following indicators: type 1 High Nature Value Farming land (i.e. high proportion of semi natural grassland and low stocking density) selected designated sites and national scenic areas; density of bird species that could be negatively affected by changes in grazing regime; significant declines (>20%) in livestock between 2005 and 2010; low average stocking density (<0.5LSU/ha); and a declining labour source measured by Standard Labour Requirements. The report was originally drafted to offer a definition of vulnerable areas that could be used for delimitation purposes and while the mapping is useful as a measure of vulnerability, the reliance on remoteness as a factor excludes the use of this exact categorisation for within-ANC payment zones. The report goes on to highlight the limitations placed on livestock farmers by biophysical constraint and poor infrastructure with many farms making a net loss when subsidy payments are deducted. Fragility is also expressed at a landscape level with knock on effects for remaining producers when one farm goes out of business, this can manifest in landscape level change and, with an aging population of land managers, a risk of depopulation. The importance of continuing farming in remote areas is emphasised in terms of the provision of public goods, maintenance of biodiversity and in providing high health status store animals to Scotland’s stratified livestock production systems. 13 http://www.gov.scot/Resource/Doc/278281/0123051.pdf 20