Homecoming Queen Gives Gift of Life WEST LIBERTY, W.Va

advertisement

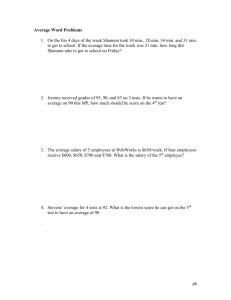

Homecoming Queen Gives Gift of Life WEST LIBERTY, W.Va. – West Liberty University’s 2008 Homecoming Queen did a remarkable thing in June. A little more than a month after graduating with her degree in Art Education, Shannon Baldauf made the 60-mile drive to a Pittsburgh hospital and gave away one of her kidneys to a person she had only met once. “A thousand things run through your mind when you get the call that they’ve found a living donor match,” said 32-year-old Jarred Lazear, who had been waiting two years for a compatible donor. “I was really curious to meet this person who was willing to go out and get tested for the purpose of giving up a perfectly healthy organ. “My folks had told me Shannon was an incredible person. When I finally got to meet her about a month before the surgery, it took me about a minute to think to myself, ‘Wow! I see what they mean.’ ” The decision to give up a kidney wasn’t something Shannon arrived at overnight. She first thought about becoming a kidney donor more than a decade ago. “When I was 12 years old,” she said, “I had a cousin who was born with only one kidney. At the time, doctors thought he might need a kidney transplant when he got older. I remember thinking, ‘Hey, I’ve got two kidneys. When the time comes, I’ll just give him one of mine.’ ” Shortly after arriving at West Liberty, Shannon was helping a fellow classmate with an internet search about organ donation and living donors. That search reminded Shannon of the commitment she had made to herself and to her young cousin several years earlier. “By then, my little cousin was doing great,” Shannon said, “so I figured if he wasn’t going to need one of my kidneys, someone else could have one. I sat down and made out a list of 15 to 20 things I wanted to do before I graduated from West Liberty. “The kidney transplant was on there but so were a bunch of other things like taking a walking tour of Pittsburgh, going to a musical, buying ice cream at the new Cold Stone Creamery at The Highlands and taking a trip to the zoo. I was 20 years old and I had never been to a zoo in my life.” The zoo trip and kidney transplant were the only items left on that list by the time Shannon marched to receive her diploma along with the rest of the University’s Class of 2009. The very next day, one of her softball teammates, Katelyn Kumm, pulled up to Shannon’s doorstep. A few hours later, Katelyn and Shannon were walking through the exhibits at the Pittsburgh Zoo. That trip to the zoo was just one example of the support Shannon received from her friends and teammates after they learned about her decision to become a living donor. “My teammates and Coach (Herb) Minch were so supportive through all of this,” Shannon said. “I found out Jarred and I were a match before Christmas break but I didn’t know when the surgery would be scheduled. “I told Coach I still wanted to play but there was a chance I might have to leave the team at some point during the season to donate my kidney. He told me to do whatever I needed to do and he’d find a way to work around it. I wound up missing a few practices with some of the testing but he was great about it. “My teammates thought it was really cool. Even though school had been out for a month by the time I had the surgery, several of them still texted me in the hospital to see how I was doing. They really mean a lot to me.” The journey that brought Shannon and Jarred together in a Pittsburgh hospital is the latest exhibit to be filed under the heading of “truth is stranger than fiction.” Although they had never met, both had been born and raised within 15 miles of the West Liberty campus and graduated from neighboring Brooke High School. In addition, their fathers – Greg Baldauf and Leonard Lazear – were friends and co-workers at WheelingPittsburgh Steel. Greg and Leonard are even part of a group of Wheeling-Pitt employees who meet for breakfast at a local restaurant several times a year. After graduating from high school, Jarred went on to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Marshall University. In June 2007, Jarred was working in Myrtle Beach, S.C. when his life was turned upside down. With no warning, his kidneys had simply stopped functioning. Jarred’s kidneys had been devastated by an exceptionally rare autoimmune disorder known as Goodpasture’s Syndrome. The natural antibodies produced by his body to defend against infection suddenly began attacking the lining of his kidneys. The illness strikes less than one of every two million people. To put that in perspective, a person is five times more likely to be struck by lightning (one in 400,000) than to contract Goodpasture’s Syndrome. “The doctors told me it usually starts in the lungs but with me it went after my kidneys,” Jarred said. “I had no idea anything was going on. My first symptom was total kidney failure.” Once his physicians confirmed the diagnosis, they were able to treat the disease but the kidney damage was irreversible. Without a transplant, Jarred now faced an intimidating laundry list of physical, dietary and liquid intake restrictions along with the prospect of spending four-hour stints hooked up to a dialysis machine every other day for the rest of his life. His name went on the national waiting list for a cadaver donor but Jarred and his family saw that option as Plan B from the start. “The prognosis for receiving a transplant from a living donor is so much better than a cadaver donor,” he said. “There’s about a 25 percent chance of finding a tissue and bloodtype match in your immediate family so that’s usually your best option.” Unfortunately for Jarred, the “best option” didn’t work out for him as none of his family members were matches. All he could do was endure the endless dialysis treatments and wait for his number to come up on the national transplant list while hoping for a miracle. Several months later, back in West Virginia, Shannon happened to tag along with her dad at one of his breakfast get-togethers with his friends from the mill. She overheard Jarred’s father talking about the family’s search for a kidney. The odds seemed astronomical but something told Shannon a chance to check the biggest item off her “university to-do list” had just dropped into her lap. She immediately volunteered to be tested. After a flurry of tests whipped back and forth between West Virginia and South Carolina over the next few weeks, doctors confirmed that Shannon’s kidney was indeed a match. “It’s mind-boggling when you think about it,” Jarred said. “Nobody in my family was a match for me and Shannon is totally unrelated to any of us. Yet, not only does Shannon turn out to be a match, she’s almost a 100 percent match. That’s incredible.” Shannon still had to go through extensive medical and psychological testing and counseling before the procedure could be scheduled but she passed with flying colors. The transplant took place June 24 at UPMC-Montefiore Hospital in Pittsburgh. Surgeons made three small holes in Shannon’s stomach for the laparascopic probes and a small 2-inch incision on her lower abdomen to remove the kidney. After coming out of the anesthesia, Shannon experienced some initial nausea from the pain medication but was resting comfortably by evening. The next morning, Shannon felt well enough to look in on Jarred and found him wide awake and sitting up in bed watching television. Less than 24 hours after transplant surgery, both patients were already well on the road to recovery. “The nurses told us we looked so good together they wouldn’t have known we were patients if it hadn’t been for the hospital gowns,” Shannon said. “They were really surprised at how well we were doing.” Three weeks later, Shannon was back at West Liberty and had already resumed her summer job helping repaint the lines on campus parking lots and traffic lanes. Shannon’s humanitarian ventures are far from over. She’s going to spend the next two years at West Liberty pursuing her master’s degree and is already looking forward to joining a chapter of Habitat for Humanity that will be forming on the campus in the fall. “The surgery didn’t hurt nearly as much as I thought it would,” she said. “I’m still not supposed to lift anything heavy for a couple more weeks but I think I could. I really feel back to normal.” Jarred moved back to the area from South Carolina this past winter after finding a job closer to home. Now a senior corporate trainer for Westinghouse Electric near Pittsburgh, he expects to be back at work full-time by the middle of August. “It’s still hard to put into words what a big change this has made in my life,” Jarred said. “I was going to the bathroom the other day and it struck me that, because of the dialysis, I hadn’t even stood in front of a urinal for two years. “We take so many things for granted when we’re healthy. I can eat a much wider selection of food now. If I want a snack, I can have one. If I’m thirsty, I don’t have to check my chart to make sure I can drink a glass of water. “But the biggest thing is I don’t have to drive back and forth to the doctor’s office every other day and get hooked up to that dialysis machine. That’s 15 hours of my life Shannon has given back to me every week. “You can’t put a price on that.”