Cyclone Nargis, Myanmar, 2008: A critique of how

advertisement

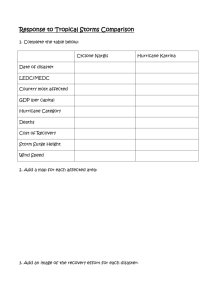

TM5563: Public Health Leadership and Crisis Management Cyclone Nargis, Myanmar, 2008: A critique of how the government managed the crisis. Assignment Two Samantha Leggett 11/10/2011 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 Contents 1: Introduction 3 2: Literature search methodology 4 3: A critique of the how the government managed the crisis 3.1 Leadership in the immediate aftermath of the cyclone 4-6 3.2 Media and communications management during the crisis 6-8 3.3 Management challenges during mass fatality/casualty events 8-9 3.4 Psychological challenges during public health crises 9-10 3.5 Ethical issues arising during the government’s crisis management 10-11 3.6 Legal aspects of public health crisis management 11 3.7 Deployment of international aid staff 12 4: Conclusion 13 5: Appendix A- Maps. Before and after 14-15 6: Appendix B- A snapshot of the aid situation in Myanmar immediately following cyclone Nargis 16-17 7: Appendix C- Immediate disaster response measures implemented by the Myanmar government following cyclone Nargis as reported by the Tripartite Core Group (2008) 18-19 8: Appendix D- Examples of how the Myanmar government’s actions may contravene international laws, humanitarian agreements and guidance 20-21 9: References 22-24 2 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 TM5563 Public Health Leadership and Crisis Management Assignment Two Cyclone Nargis, Myanmar, 2008: a critique of how the government managed the crisis. 1: Introduction Cyclone Nargis, the worst natural disaster to strike Myanmar in recorded history and one of the deadliest cyclones of all time, swept across the south west of the country in early May, 2008. Winds of up to 240 kph triggered a huge tidal surge that swept some twenty five miles inland which left around 140,000 people declared dead or missing, over 19,000 injured and rendered hundreds of thousands homeless and vulnerable to further injury and disease. Areas of the Ayeyarwady (Irrawady) Delta and parts of Bago division and Mon state were devastated and the former capital Yangon (Rangoon) and its district also suffered. It is estimated that up to 2.4 million people were severely affected by the cyclone (see Appendix A). Many lost family members, their homes, food reserves, livestock, tools and livelihoods in areas that were remote, heavily populated, difficult to access and already vulnerable. Up to 800,000 people were displaced and critical infrastructure including electricity, communication and transportation networks, health facilities (75% destroyed) and schools (50-60% destroyed) across an area half the size of Switzerland sustained massive damage. The scale of the disaster has been compared to that experienced by Aceh, Indonesia, one of the worst affected areas during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.1-8 In times of public health crisis, strong leadership is essential to guide and reassure communities, as well as in co-ordinating an effective intra-agency response. The literature highlights that how a public health crisis evolves is greatly influenced by its leadership.9-11 In addition to the leadership displayed in the immediate aftermath of a public health disaster, other key areas of consideration are: management of the media and communications; management challenges during mass fatality/casualty events; psychological challenges; ethical and legal considerations; and the management of international aid staff. Using these key considerations as building blocks this paper will offer a critique of the leadership provided by the government of Myanmar following cyclone Nargis in 2008. 3 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 2: Literature search methodology Initial searches using the term ‘cyclone Nargis’, with no limits and utilising the following sources yielded few results: Ovid produced forty three potential references, six of which were selected; Medline, CINAHL and CABI produced zero results; PsycInfo produced six potential references, two of which were selected. JCU OneSearch was then utilised; again the term ‘cyclone Nargis’ was entered and the search was limited to scholarly publications with full text online in English. Three hundred and twenty one papers were initially listed, fifty nine of these were selected for review and fifteen articles finally selected for relevance. Following this Google Scholar was searched using the same criteria but produced no new relevant results. A more expansive search was then conducted using Google with the following criteria: cyclone Nargis; cyclone Nargis Burma crisis management; cyclone Nargis Myanmar crisis management; cyclone Nargis leadership, cyclone Nargis public health. Innumerable results were yielded from these searches and this is where the majority of the material to inform this paper was taken from. The resources and publications sections of websites belonging to UN agencies, international nongovernmental organisations, humanitarian agencies (such as AlertNet and Relief Web) and governmental agencies were also searched for relevant literature. International media agencies websites were also searched (BBC, Reuters, CNN, Associated Press) for news items and visual media. Finally, the reference sections of all selected articles and reports were reviewed for further relevant material. 3: Critique 3.1: Leadership in the immediate aftermath of the crisis Myanmar is ruled by a military junta who are widely known to have a deep mistrust of the outside world.12 Immediately following the cyclone, the commander-in-chief of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), Myanmar’s ruling party, General Than Shwe declared that Myanmar was capable of handling the relief effort.7 A national emergency was declared in the five worst-hit regions and the government mobilised its National Natural Disaster Preparedness 4 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 Central Committee (NDPCC) which is chaired by the Prime Minister. The Tripartite Core Group (TCG) (2008)13 documents these activities in the Post Nargis Joint Assessment (PONJA), a summary of which can be found in Appendix B. Lateef (2009) asserts that preparedness is the key to preserving human life and health in the event of natural disasters. An absence of emergency preparedness will result in greater immediate mortality during the impact phase (for example due to a lack of an early warning system) and a greatly increased risk of morbidity and mortality immediately following the disaster (for example due to delays in establishing food and water security).14 One of the first emergency response measures employed by the government was to deploy the Tatmadaw (armed forces) to the affected areas. Selth (2008) asserts that the Tatmadaw is the only organisation in Myanmar with the command structure, internal communications, manpower, resources and expertise to respond quickly to such a catastrophic event. However, although an early intervention, they were not mobilised immediately and when they eventually were, some days after the cyclone, the response was assessed as patchy and weak.15 Seekins (2009) contends that not only does the Tatmadaw have poor infrastructure, it also suffers from a lack of training and experience in disaster relief and operates with ‘backward’ technology.12 While acutely aware of the shortcomings of the SPDC, it is acknowledged that far richer, technologically more advanced countries have experienced difficulties in responding appropriately to disasters of such scale.15-17 However, it is asserted that by any measure, the SPDC’s response was lacking, particularly when it had the means to take some action. Essentially, what the SPDC were seen as doing was denying relief to hundreds of thousands, if not millions of people at real and immediate risk of death.18 After three weeks of diplomatic negotiations with the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon1, the junta finally consented to foreign aid, albeit under tight restrictions. It was agreed that the 1 Ban Ki-Moon’s negotiations with the government were seen as unprecedented; never before had a UN Secretary General found it necessary to travel to a disaster affected country to plead with a head of state to open its borders to relief aid and international disaster experts (Stover E, Vinck P. Cyclone Nargis and the politics of relief and reconstruction aid in Burma (Myanmar). JAMA 2008; 300(6): 729-731). 5 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) would establish a humanitarian taskforce to lead and facilitate the international response and act as mediators between the military and the international community (see Appendix C).1,3,4,6,7,15 Despite this seemingly key breakthrough for the international aid community and the emergency response measures reportedly implemented by the government, many actors report ongoing leadership issues in the weeks following Mr Ban’s negotiations, the most significant being lengthy visa processing times even once permission for access had been granted, restrictions on internal movement (including the need to be accompanied by government officials on all missions), military checkpoints in place to the worst affected regions, fragmented and unclear leadership demonstrated by a lack of clarity on which agencies were taking the lead on which aspects of managing the crisis, and a lack of momentum in the activities that were initiated. 3,4,13,14,17,19-21 Ongoing infrastructure issues also presented barriers to effective aid delivery: weak telecommunications networks, lack of appropriate transportation, damaged road networks, lack of any banking systems and poor fuel supply. This is in contrast to the fact that the government of Myanmar document in the PONJA that in the Yangon division, within four days of the cyclone a temporary communications system had been installed, the main roads had been cleared and additional fuel supplies had been provisioned.3,4,13,14,17,19-21 3.2: Media and communications management during the crisis Goldsmith (2001) states that ninety percent of serious controversies arise from misunderstandings and advises that words and messages should be chosen carefully.10 However, Gray and Ropeik (2002) warn that communication is effective not only through what is said, but also in actions taken (or not) by leaders.22 For over a week after Nargis hit few were aware of exact ground conditions. Information was sporadic, unreliable and oftentimes conflicting coming from satellite images, patchy evidence from national aid agency staff, the official state media, international news agencies, amateur videos, Burmese exiles, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and humanitarian news networks.1,3,18,19 6 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 The unreliable media coverage, combined with a lack of in-country communications had serious implications for needs assessments, monitoring and accountability of international agencies. The ability to collect and synthesize different types of information has the potential to make a significant difference in humanitarian performance, particularly within the context of Myanmar.19,23 Press coverage of human suffering after a disaster is also critical for attracting donations and in this instance, the international media are said to have played an ambiguous role in the relief efforts. While state media devoted more attention to a constitutional referendum2 than to the disaster, much of the international media coverage focused on the government’s alleged diversions of aid, appalling human rights record, its obvious lack of concern for the cyclone victims and its blatant disregard for world opinion.12 The government strongly objected to this international media coverage and reacted by closing down all access for journalists and foreign aid workers to the worst affected areas and arresting local people who provided visual footage.19 This is thought to have affected donations, with donors understandably questioning whether their money would actually reach the survivors.3 Seekins (2009) argues that the blame for this should not be laid at the feet of the world’s media- the greatest impediment to the flow of humanitarian 2 ...“While the Constitution Drafting Commission with 54 members and chaired by the Chief Justice was still formulating the draft constitution based on the detailed principles endorsed by the National Convention (1993-2007), the SPDC made a surprise announcement on 9 February 2008 that a constitutional referendum would be conducted in May with “multi-party democracy general elections” scheduled for 2010. The completion of the draft constitution was announced on February 19. This was followed on 26 February by the promulgation of “The Referendum Law for the Approval of the Draft Constitution” chaired yet again by the Chief Justice. On 9 April it was announced that the referendum would be held on the 10 May in conformity with “international standards”. Only then, the Myanmar version of the draft constitution went on sale in Yangon. It was apparent from all these successive pronouncements within a short period of two months (leaving little time for the opposition to mount an effective campaign) and the fact that the word “approval” figured prominently in the titles of the referendum law and referendum commission that the junta was determined to ensure that the new state constitution would be adopted, leapfrogging over the political dialogue process aimed at reconciliation between Daw Aung San Suu Kyi (the leader of the opposition National League for Democracy) and the government which was initiated in 2007 by Professor Gambari, the special advisor to the UN Secretary General. NB calls by Professor Gambari and some Western governments to allow international observers also went unheeded and the draft constitution drew harsh criticism and calls for rejection [by many actors, both nationally and internationally] who accused the SPDC of perpetuating military control under the guise of a civilianised political regime and skewed electoral rules”...The referendum went ahead on the 10 May except for in the 47 townships severely affected by the cyclone where the voting date was postponed until 24 May (Maung Than TM. Myanmar in 2008: Weathering the Storm. Southeast Asian Affairs 2009; 1: 195-222). 7 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 aid into Myanmar is the junta’s policies and attitude toward foreign aid agencies working in the country and these were known well before the disaster struck.12 The media have been identified as an essential tool for effective communications during public health disasters and it is advised that they are made an ally by crisis managers. The information supplied to them must be of quality, relevant and trustworthy; providing timely first hand news will invariably help to strengthen media relations and can disable speculation and rumour and help to allay public fears and risk misperception.24,25,26,27 The junta seem not to have taken this into consideration or, simply did not care. Selth (2008) warns of the dangers of politicising humanitarian missions, indicating that words may only serve to make finding a viable solution to a complex problem much more difficult.15 However, Chan (2008) asserts that the interests of governing nations will inevitably assume a role in how disasters are managed2 and Seekins (2009) argues that treating a natural disaster as a non-political issue is a mistaken approach. The junta’s approach to the devastation caused by Nargis demonstrates that failure to provide adequate relief is not merely related to technical and personal problems caused by poor infrastructure, sub-standard management or low levels of training; nor is corruption the only problem.12 3.3: Management challenges during mass fatality/casualty events Following natural disasters, mismanagement of the dead has consequences for the psychological wellbeing of survivors. Moral and legal implications are also highlighted: body recovery and storage; identification; and disposal of human remains.28 Following cyclone Nargis it was unlikely that the bodies of tens of thousands of people would ever be identified; they were washed far from their homes by the tidal surge and quickly became badly decomposed. Additionally the force of the surge stripped many of their clothes and any identifying items.29 Morgan et al. recognise that rapid decomposition makes identification nigh on impossible within a few days and that developing countries are unlikely to have the technology or capacity to conduct forensic identification of mass fatalities. Lack of a national mass fatality preparedness plan and lack of an international agency providing technical support will hinder efforts to locate, identify and provide appropriate burials for mass fatalities.28 The quality and timeliness of the 8 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 response is also implicated and government restrictions on access to the Delta are likely to have exacerbated the situation. 29 Morgan et al. further assert that emergency response should not add to the distress of the affected communities and emphasise the rights of survivors to see their dead treated with dignity and respect. Close work with the media is highlighted as a means of avoiding misinformation and promoting these rights.28 It is additionally suggested that military agencies should incorporate both the practicalities and the legal, medical, social and psychological aspects of mass fatality management into the training of medical and paramedical personnel and include it in their strategic and tactical planning.30 More than five weeks after the cyclone the situation on the ground remained desperate. Bloated and disfigured bodies still littered the Delta area- local villagers report being overwhelmed by the numbers of bodies washing up on beaches and appearing in the rivers. Without the means for identification villagers said that they had been burying people in mass graves. Only some had been marked and then, only with wooden sticks.29,31 International news documentaries showed government officials dumping bodies into the rivers in full view of, and next to temporary shelters housing thousands of survivors.32 3.4: Psychological aspects of public health crisis management In a mass fatality and casualty situation, the psychological impact and significance of the effects of trauma both in survivors, rescue workers, the media and the community as a whole should not be overlooked.14,30,33 It has been demonstrated that rescue workers specially trained in mass fatality management can experience double the incidence of post traumatic stress after a mass fatality event. Further, it is recognised that in a large or complex mass fatality event, aid staff may have to work outside of their usual remit and untrained individuals may have to assist with management of the dead, deal with bereaved families and may have suffered loss themselves.34 It is noted that early on after the cyclone, many survivors were in urgent need of counselling and psychiatric care, particularly those traumatised by the loss of family members; up to 30% of 9 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 households reported mental health problems as a result of the cyclone3.12,13,33 A Lack of coordination and preparedness will likely cause tension amongst survivors and also add to the confusion and stress of relatives searching for family members.34 Van Ommeren et al. (2005) give value to mental health interventions in order to reduce both the physical and psychological burden of disasters in resource poor settings. They recognise that post traumatic stress can be disabling and promote ongoing community based social interventions as an effective method of mitigating this. A reliable flow of credible information is implicated in the immediate aftermath of a disaster in order to facilitate the delivery of appropriate mental health services both to survivors and workers, and access to valid information is asserted as a basic right.35 3.5: Ethical issues arising during the government’s crisis management In the case of cyclone Nargis three main ethical issues arise from the literature: 1) Immediately following the cyclone, when disaster management should have been the priority, the government went ahead with the country’s planned constitutional referendum; 2) What the outside world saw as a humanitarian catastrophe appeared, for the regime, first and foremost a political and security threat with extreme media suppression seen as a key indicator of this; and 3) due to the embargo on international aid and the government’s preoccupation with the referendum, national actors had to lead the humanitarian response unsupported-many of these individuals were bereaved and some organisations had lost staff in the cyclone.8 That the government had neither the experience nor the technology to manage a relief and recovery operation of this scale was recognised early on by a number of high ranking officials who were directly involved in the relief efforts. The gravity of the situation and urgent need for 3 Triggers for mental health problems could be due to the fact that many had lost all of their clothes in the cyclone and storm surge and had resorted to taking clothes from dead bodies; people were experiencing ’flashbacks’-still able to feel the hands of those they were trying to save and were forced to let go of; many were also worried about their livelihoods-they were without shelter and had no seeds left to plant in order to gain income (Medecins Sans Frontieres. After the deadly storm. Mental Health Practice 2008; 12(2): 14-17). Further, for a considerable time after the tidal surge, human bodies were still evident in many places (Seekins DM. State, society and natural disaster: cyclone Nargis in Myanmar (Burma). Asian Journal of Social Science 2009; 37: 717-737). . 10 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 international assistance were conveyed to UN officials.3,36 There has been much speculation whether it took some time for this same realisation to filter up to the leadership, or whether they deliberately decided to delay opening the country up to international relief agencies until after the referendum.15,36 It is reported that in some locales, survivors of the cyclone were evicted from schools and other public buildings to make room for voting booths. International media widely perceived this act as a means of the military government safeguarding its own interests rather than those of its citizens. In the government’s mind, the suffering and chaos particularly in the Delta region, where local administration had broken down, heightened the risk of social unrest at a time when local tensions were already running high over the prioritisation of the constitutional referendum.3 Maung Than (2008) strongly contends that the economic damage and losses, though considerable, were not so crippling as to force a crisis situation that could lead to serious unrest.5 3.6: Legal aspects of public health crisis management Following the evictions in late May to make way for voting locations, it is further reported that in early June, the Myanmar government began forcibly removing internally displaced persons (IDPs) who had been sheltering in monasteries, schools and other public buildings and ordering them back to their homes or to military controlled camps.7 This is despite an assessment finding that in cyclone affected areas 57% of homes were totally destroyed and 25% of homes had been partially destroyed.3 Under international law, those made homeless by the cyclone are considered internally displaced.18 The primary duty and responsibility for the protection of IDPs and the administration of humanitarian assistance to them lies with national governments.37 Kauffman and Kruger (2010) contend that the Myanmar government does not recognise the concept of IDPs.4 However, as a member of ASEAN, Myanmar has signed the agreement on ‘Disaster Management and Early Response’ and thereby has international commitments to uphold in regard to international cooperation, coordination and relief and rehabilitation after humanitarian disasters.18 11 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 In both its resistance to international aid efforts, restrictions placed upon internal movement, harassment and intimidation of private relief workers, forced population movement, misappropriation and confiscation of aid and controls over information the government would appear to contravene a number of international laws and humanitarian agreements and guidance and may have committed crimes against humanity (see Appendix D). 16,38 3.7: Deployment of international aid staff In reviewing the literature on the response to cyclone Nargis, management challenges surrounding the deployment of international aid personnel are minimally discussed. However, within this context two related issues stand out. The choice and numbers of personnel deployed should be decided upon information available via ground reports, media reports and other verified feedback channels pertaining to, amongst other aspects: number of fatalities/casualties; mechanism of injury; and expected procedures and disease. Language competency may also be a consideration.14,19 As previously discussed at length in section 3. 2, information channels were suppressed, sporadic and deemed unreliable. This would have implications for both the selection and preparation of relief personnel about to be deployed. Brondolo et al. assert that as equipment and medication (for example) are routinely provided to ensure the physical safety of relief personnel, we can and should therefore also provide safety procedures to protect emotional and intellectual functioning.34 WHO (2008) emphasise the importance of pre departure briefing regarding psychological preparation and stress management. As seen in the wake of cyclone Nargis, teams may be confronted and have to deal with the handling of many dead bodies. The emotional overload, which can be expected, in performing such an unusual and heavy task without specific training, can provoke significant reactions of traumatic stress and even lead to psychological trauma, or a rapid onset of burnout. Even if this is not avoidable, good preparation can be useful for preventing, or at least limiting stress by providing personnel with effective stress management strategies for example. The importance comprehensive pre departure preparation is stressed, but it is also acknowledged that limitations are imposed by short notice departures.39 12 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 4: Conclusion This critique demonstrates that all aspects of public health leadership and crisis management are closely intertwined, for example, mass casualties cannot be dealt with without the legal and psychological implications being considered; the preparation of international aid staff for deployment must include psychological preparation and leadership itself should surely be based on sound ethics and effective communication. A lack of preparedness can add to the psychological stress of all those involved and ineffective communication can be implicated in poor media coverage and difficulties in preparing relief personnel and supplies appropriately. The government of Myanmar seem not to have taken any of these aspects of public health leadership and crisis management into consideration during their response to cyclone Nargis. They initially failed to understand the scale of the devastation and over-estimated the state’s capacities. Military rulers put their security and political agenda first, prioritising the constitutional referendum at the expense of the people’s welfare. And, much of what the government did do to try to help survivors was undermined by a lack of communication, petty corruption and sheer incompetence. Thus presented, is therefore an example of how not to manage a public health crisis. 13 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 5: Appendix A Satellite maps of the areas affected by cyclone Nargis-before and after 1: Before the cyclone, April 15th 2008 2: After the cyclone, May 5th 2008 14 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 3: Satellite detected flood waters, May 5th 2008 4: Estimated population affected in flooded areas Maps taken from: New York Times (2008). Mapping the Aftermath of Cyclone Nargis. (May 8th 2008) [cited 2011 November 5]. Available: Online 15 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 6: Appendix B A snapshot of the aid situation in Myanmar immediately following Cyclone Nargis. Relief flights into Yangon were accepted but on the proviso that the Myanmar government had control over aid distribution. Aid organisations soon expressed concerns that food was being diverted away from the communities and into the hands of military officials. Offers from French and American ships to deliver aid via sea ports were repeatedly rejected. British, French and US navy ships laden with supplies, heavy-lift helicopters and other equipment idled in Thai waters while seeking permission to enter. Navy ships eventually offloaded their supplies in Thailand for onward transportation by civilian agencies. World Food Programme airlift supplies were allowed into the delta but only in late May and after being repeatedly impounded. Medical teams from neighbouring South East Asian countries were permitted entry The Myanmar Red Cross Society set up ‘aid stations’ in a few affected townships Foreign aid workers already in the country faced tight restrictions on access, especially in the worst-affected areas of the delta. A few were able to deploy during the first week but most were delayed by government policies requiring international staff to have permits for all travel outside of Yangon and be accompanied by a government official. From the second week after the cyclone, military checkpoints were set up on roads into the delta and access for foreigners was blocked. The army refused permission for international relief flights to go directly to the military airport in Bathein, which could have reduced delays from overland transport from Yangon along quickly deteriorating roads. Even before the cyclone many areas had only been reachable by foot or small boat. Faced with the suffering of their fellow countrymen and women and the obvious shortcomings of the official relief operation, thousands of ordinary people from Yangon and further afield began heading into the delta region with relief supplies. Some groups got through, while others were stopped at government roadblocks and ordered to 16 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 handover their supplies to the government for distribution. Several of the people involved in these private relief efforts were arrested for allegedly engaging in ‘subversive activities’, which it is alleged, in the governments’ terminology can simply entail discussion with foreign media. From May 12 to June 22 the US Department of Defence (DOD) completed 185 airlifts to deliver emergency relief supplies via implementing partners. 1,3,20,42 17 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 7: Appendix C Immediate disaster response measures implemented by the Myanmar government following the cyclone as directly reported by the Tripartite Core group (2008).13 A meeting of the NDPCC was held on the morning of May 3rd where ten emergency disaster response sub-committees were formed to work in close collaboration and to deal with: News and information Emergency communication search and rescue Assessment of emergency relief Confirmation of loss and damage Transportation and route clearance Natural disaster reduction and emergency shelter provision Healthcare Rehabilitation and reconstruction Security Additionally individual ministers were assigned to each township to help coordinate the response. The government immediately commenced relief and rehabilitation operations including setting up relief camps, field hospitals, verification and cremation of the dead, installation of a temporary communications system, clearance of the main roads, provision of fuel, opening of markets and restoring security. It is stated that the reinstallation of electricity and water and renovation of hospitals were completed in four days in Yangon division. It is also reported that the Tatmadaw, in the immediate aftermath of the cyclone provided substantial assistance in relief and early recovery efforts including: Search and rescue; evacuation of the injured; establishing camps for the displaced; loading and unloading of relief goods; and distribution of aid. Doctors and nurses from the defence services provided emergency medical care in the affected areas. 18 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 The air force placed helicopters at the disposal of the relief operation for distribution of supplies and evacuation of people from affected areas. Six teams of psychiatrists provided mental health care in the camps and with the mobile health teams. An adequate supply of essential medicines and equipment were provided to the cyclone hit regions by the MoH. The report states that: ...“the Tatmadaw made a valuable contribution by calming fears, providing security and maintaining peace and harmony in affected areas” and goes on to point out that as a result of the provision of efficient and continuous medical care by the MoH (as well as from other (unnamed) sources) the health situation of the people in the cyclone hit regions is improving day by day without any serious complications. 19 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 8: Appendix D Examples of how the Myanmar governments’ actions may contravene international laws, humanitarian agreements and guidance. The United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, Principle 15 (d) states that: ... “Internally displaced persons have the right to be protected against forcible return to or resettlement in any place where their life, safety, liberty and/or health would be at risk”... Principle 18: 1 states that: ... “all internally displaced persons have the right to an adequate standard of living” and 18:2 that: ... “at the minimum, regardless of the circumstances...authorities shall provide...and ensure safe access to: essential food and potable water; basic shelter and housing; appropriate clothing and essential medical services and sanitation”. Principle 25:2 states that: ...consent to international humanitarian assistance... “shall not be arbitrarily withheld, particularly when authorities concerned are unwilling or unable to provide the required humanitarian assistance” and 25:3 dictates that: ...all persons engaged in the provision of humanitarian assistance should be granted... “rapid and unimpeded access to the internally displaced”.... (UNHCR, 2001). Myanmar has ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) which recognises the rights of children (those aged 18 years and under) to health and life, and demands international cooperation in order for countries to achieve this. It is a legally binding instrument and requires that Signatories must “promote and encourage international cooperation with a view to achieving progressively the full realisation of the right”. 20 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 For example, Article 24 states that all children have the right to...”the highest attainable standard of health...[including access to]...primary health care...nutritious foods and clean drinking water”. By agreeing to undertake the obligations of the Convention, national governments commit themselves to protecting and ensuring children’s rights and have agreed to hold themselves accountable for this commitment before the international community.38,41,42 21 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 9: References 1. AlertNet. Myanmar cyclone. Worst Asian cyclone since 1991; 28 April 2010 [cited 2011 October 3]. Online. 2. Chan JL. Politics and disaster response: recent experience in Asia. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2008; 2(3): 136-138. 3. International Crisis Group (ICG). Burma/Myanmar after Nargis: time to normalise aid relations. Asia report No 161-20 October 2008 [cited 2010 October 4]. Online. 4. Kauffman D, Kruger S. IASC cluster approach evaluation, 2nd phase country study, April 2010, Myanmar [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 5. Maung Than TM. Myanmar in 2008: Weathering the Storm. Southeast Asian Affairs 2009; 1: 195-222. 6. Medecins Sans Frontieres. Field News: one month after cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar, survivors still living in dire conditions; 2008 [cited 2010 October 31]. Online 7. Stover E, Vinck P. Cyclone Nargis and the politics of relief and reconstruction aid in Burma (Myanmar). JAMA 2008; 300(6): 729-731. 8. UNDP. Community-driven recovery: cyclone Nargis one year on; 2009 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 9. Boehm A, Enoshm G, Michal S. Expectations of grassroots community leadership in times of normality and crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2010; 18(4): 184-194. 10. Goldsmith B. Leading in a crisis. High Volume Printing 2001; 19(5): 18-19. 11. Boin A, ‘t Hart P. Public leadership in times of crisis: Mission impossible? Public Administration Review 2003; 63(5): 544-553. 12. Seekins DM. State, society and natural disaster: cyclone Nargis in Myanmar (Burma). Asian Journal of Social Science 2009; 37: 717-737. 13. Tripartite Core Group (TCG). Post-Nargis Joint Assessment; 2008 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 14. Lateef F. Journal of Emergencies, trauma and shock 2009; 2: 106-114. DOI: 10.4103/0974-2700.50745. 15. Selth A. Even paranoids have enemies: cyclone Nargis and Myanmar’s fears of invasion. Contemporary Southeast Asia 2008; 30(3): 379-402. 22 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 16. Suwanvanichkij V, Murakami N, Lee CI, et al. Community-based assessment of human rights in a complex humanitarian emergency: the Emergency Assistance Teams-Burma and Cyclone Nargis; 2010 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 17. UNICEF. Best practices and lessons learnt. UNICEF Myanmar’s response following cyclone Nargis; 2009 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 18. Hattotuwa S. Cyclone Nargis: lessons and implications for ICTs in humanitarian aid; 2008 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 19. ALNAP. Cyclone Nargis: lessons for operational agencies; 2008 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 20. Humanitarian Accountability Partnership (HAP). HAP and Sphere support program in Myanmar following cyclone Nargis. Case study-June 2009 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 21. Ternstrom B, Yamato M, Myint S, et al. Evaluation of CARE Myanmar’s cyclone Nargis response; 2008 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 22. Gray GM, Ropeik DP. Dealing with the dangers of fear: The role of risk communication. Health Affairs 2002; 21(6): 106-116. 23. Jordt I. In the wake of cyclone Nargis. Food security, information flows and foreign aid. Anthropology News 2008; 49(7): 19-20. 24. Moe TL, Pathranarakul P. An integrated approach to disaster management. Disaster Prevention and Management 2006; 15(3): 396-413. 25. Chess C, Clarke L. Facilitation of risk communication during the anthrax attacks of 2001: The organizational back-story. American Journal of Public Health 2007; 97(9): 15781583. 26. Khodarahmi E. Strategic public relations. Disaster Prevention and Management 2009; 18(5): 529-534. 27. Rahm D, Reddick CG. US city managers’ perceptions of disaster risks: Consequences for urban emergency management. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 2011; 19(3): 136-146. 28. Morgan OW, Sribanditmongkol P, Perera C, et al. Mass fatality management following the South Asian tsunami disaster: case studies in Thailand, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. PloS Med 2006; 3(6): e195. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030195. 23 Samantha Leggett SN: 12494652 29. Associated Press. Tens of thousands dead from cyclone Nargis may never be identified. The Irrawady June 8th 2008 [cited 2011 November 3]. Online 30. Hooft PJ, Noji E, Van de Voorde HP. Fatality management in mass casualty incidents. Forensic Science International 1989; 40: 3-14. 31. BBC. Burma cyclone in video 2 June 2008 [cited 2011 November 7]. Online and Online. 32. CNN. Dead are thrown into the rivers as the living wait for aid; 2008 [cited 2011 November 4]. Online. 33. Medecins Sans Frontieres. After the deadly storm. Mental Health Practice 2008; 12(2): 14-17. 34. Brondolo E, Wellington R, Brady N, et al. Mechanism and strategies for preventing posttraumatic stress disorder in forensic workers responding to mass fatality incidents. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2008; 15: 78-88. 35. van Ommeren M, Saxena S, Saraceno B. Mental and social health during and after acute emergencies: emerging consensus? Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2005; 83: 71-76. 36. The Economist. Asia: the regime is satisfied; Myanmar’s cyclone May 17 2008; 387(8580): 72. DOI:10.1186/1752-1505-4-8. 37. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement; 2001 [cited 2010 October 31]. Online. 38. Kraemer JD, Bhattacharya D, Gostin LO. Blocking humanitarian assistance: a crime against humanity? The Lancet 2008; 372(9645): 1203-1205. 39. World Health Organization. Communicable disease risk assessment and interventions. Cyclone Nargis: Myanmar 2008 [cited 2011 October 4]. Online. 40. USAID. Fact Sheet 1 Fiscal Year 2009. Burma- Cyclone [cited 2011 November 8]. Online. 41. UNICEF. Convention on the Rights of the Child [cited 2011 November 7]. Online. 42. UNICEF. FACT SHEET: A summary of the rights under the Convention of the Rights of the Child [cited 2011 November 7]. Online. 24