Picture

advertisement

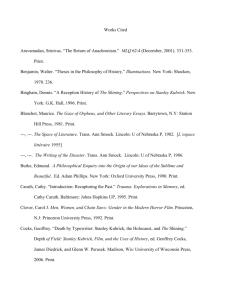

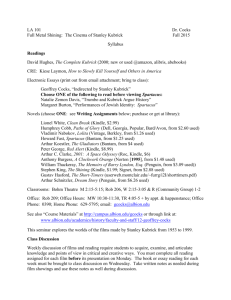

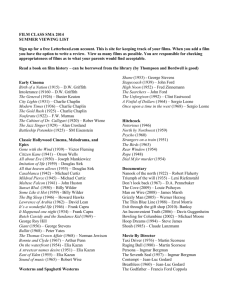

Auteurs Of Cinema: Stanley Kubrick Conall Melarkey Auteurs Of Cinema: Stanley Kubrick - By Conall Melarkey An auteur is someone who reinvents cinema - an undoubted master, an icon of influence, a unique, formidable voice and vision. Someone who aggressively manages to turn the medium of film inside out and change the way it is to be seen for the rest of its lifespan. Stanley Kubrick was an auteur. The infamous ‘Kubrick Stare’ Stanley Kubrick is considered to be one of the finest filmmakers in the history of cinema, an artist of great intellect, who challenged his audience as if they were opponents in his game of chess, exposing many generations to new ways of thinking and different perceptions of cinema, and the world, as we know it. Whether he was dissecting the topics of good, evil, war, time, space, lust, sanity (or indeed ‘insanity’), he always made them his own, in a way that can only be described as ‘Kubrickian’. Since 1954, the theory of the ‘Auteur’ in cinema has been an essential, domineering foundation in the world of film criticism. It is a theory that suggests how it is the creative, distinctive voice of the director behind a film, which makes it become not just a piece of story-on-celluloid, but rather an indispensable facet of modern culture. It is the director’s vision that drives the film to become something of an artwork and an exhibition of virtuosity. Due to the impact of the auteur theory, under the European Union, it has become a law that the director is to be reflected as the author (or one of the authors) of a film1. The word ‘auteur’ is in fact French for ‘author’, which takes us to the origins of the auteur theory. One of the domineering voices in the creation of auteur theory is the French filmmaker and critic Francois Truffaut. Truffaut, who is well known for making films such as ‘The 400 Blows’ and ‘Jules and Jim’, developed his theory whilst writing for the French film magazine ‘Cahiers Du Cinema’. The theory would also travel in later years through the writings of American film critic Andrew Sarris. Truffaut examined his theory through one of his idols, Alfred Hitchcock, which can be cited through the famous ‘Hitchcock/Truffaut’ interviews from 1962. In Truffaut’s article on Auteur Theory, he makes a detailed list of the elements required for one to be considered an auteur in filmmaking. This essay will attempt to analyze how Stanley Kubrick ticks all the boxes and should be seen as one of cinema’s great auteurs. Stanley Kubrick was born on July 26 1928 to Jacques and Sadie Kubrick. Kubrick’s parents were of Austrian, Romanian and Polish origin, but raised Stanley in apartment 2160 at Clinton Avenue in The Bronx section of New York2. Although his father was a successful doctor, a family friend notes that how Kubrick and his mother were “Such regular people, and had no hairs about them”3. At the age of thirteen, Kubrick’s father bought him his first camera. Although Stanley was a poor student at his local High School, his father was very supportive when Stanley announced that he wished to pursue a career as a photographer4. Kubrick would become an apprentice photographer for Look magazine in 1946, shooting hundreds of picture essays for the popular publishing unit. It was Kubrick’s early love of photography and his unique obsession with light and composition that leads to one of the first issues raised in Francois Truffaut’s auteur theory – visual trademarks. Truffaut voiced how distinctive trademarks in a director’s film could characterize his/her body of work and make them instantly recognizable. Film director William Friedkin states how “if you walked into a Kubrick film half-way through, just by the visuals, you could tell that it was a Kubrick film”4. Like a great painter would have an iconic vision, examples being Picasso with Cubism, Van Gogh with his abstract impressionism, Stanley Kubrick could be put along the great pantheon of any visual artists, let Still from ‘Barry Lyndon’ alone filmmakers, as he constructed his films like unique, visionary paintings. Stanley Kubrick has many visual trademarks within his body of work that make them considerably ‘Kubrickian’. Kubrick’s mesmerizing flair with light was one such example of his brilliance and innovation as a craftsman in film. His 1975 film ‘Barry Lyndon’ remains to this day as one of the most exemplary uses of lighting in film history. Kubrick often included the light sources in the frames of his films – in ‘Barry Lyndon’ we see various uses of very effective natural lighting, with such sources as visible candles and intense backlighting through the large windows seen in mansions and castles. Kubrick modeled these frames and visuals on the lighting seen in 18th century paintings. Kubrick stated that he had “created a picture file of thousands of drawings and paintings for every type of reference”5. Kubrick’s use of lighting in the earlier half of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ reveals that he was an absolute master at making the normal world appear more dreamlike. In ‘A Clockwork Orange’, before the wicked Alex DeLarge undergoes his mind aversion therapy, his ideal perspective of London appears surreal and trancelike, credited to Kubrick’s neon/noir lighting. But after Alex is deprived of his free will by the government, the film appears more mundane and less bizarre, as Alex is experiencing the isolation of the ‘real world’. Even in ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ as Dr. William Harford, played by Tom Cruise, undertakes a night of adventure and temptation throughout New York City, a similar effect is applied to the city’s streets, making them appear more illusory, allowing us to question Harford’s state of consciousness. The camerawork of Kubrick’s films were also extremely effective in the creation of mood and atmosphere, particularly his iconic use of tracking shots. In his horror classic ‘The Shining’, Kubrick is constantly moving the camera in the vast, grand emptiness of the Overlook Hotel, slowly, even if there is no one in the frame. The technique Kubrick adapts to his film indicates some sense of life or movement, even if we cannot see that moving, living thing. The results are surprisingly creepy and foreboding. One of the most famous examples of the ‘Kubrick tracking shot’ was the forward tracking shot from ‘Paths Of Glory’, in which Kirk Douglas treks through the murky trenches of WW1. Through this simple, yet technically effectual sequence, Kubrick manages to convey the emotion, depression and anti-war ideology of the story, without a single word said. Kubrick’s use of ‘one-point perspective’ in ‘The Shining’ One of Kubrick’s other trademarks was his use of symmetry and one-point perspective, in which everything appears to vanish into one point within the frame, usually towards the center. The way Kubrick meticulously constructed his visuals, and the intense research he applied to the framing and lighting in films like ‘Barry Lyndon’, clearly revealed that he was a total perfectionist, probably cinema’s greatest perfectionist. But how does this mentality fit into auteur theory? Well, Truffaut declares how it is important for auteurs to include their own “personal experiences” in their work, along with their personal “psychological realism”6. Kubrick was often criticized for not making his films personal enough, due to the intense, psychological themes, and extreme characters viewed in his work, but is that entirely true? Steven Spielberg doesn’t think so: “I envy Stanley for all those years he worked at home, within eyeshot of his kids growing up and his pets and his wife, and all of his colleagues. I loved working from the house and I understand why Stanley loved working from the house, because his films were personal, his life was personal. Everything about him is personal and being at home and not being in an office is a whole different way of getting close to that Zeitgeist”7. The way in which Kubrick brought his films into his life so extensively, in order to achieve the exact details he required, and the exact details we see on screen in his work, tells us a lot about him. We learn that we was a totally meticulous, precise, fastidious craftsman, who loved his films so much that he made them a large part of his life. If it is usually perceived that Stanley Kubrick never made personal films, then that perception could be altered by the fact that we learn more about Stanley Kubrick through his art than almost any other filmmaker. It is noted how auteurs tend to deal with an underlying theme that runs through the majority of their work. For example, Alfred Hitchcock primarily studied the theme of the everyday man entangled in a situation he cannot fully comprehend. Early in his career, Stanley Kubrick once said, “We are capable of the greatest good and the greatest evil, and the problem is that we often can’t distinguish between them when it suits our purpose”8. This was a major arc that travelled through the stories that Kubrick chronicled, the idea of two conflicting attitudes battling for control: whether it be good or evil, dreams and reality, man or machine. The duality of mankind and the battle between two opposing mentalities is hugely evident in almost the entirety of Kubrick’s work. In the poster for ‘Full Metal Jacket’, we see a helmet with the words ‘Born To Kill’, scrawled across it, but it also has a peace badge attatched to it, depicting, as Private Joker calls it, ‘The Duality Of Man’. ‘Full Metal Jacket’ was a dark study in the transformation of innocent beings into ruthless killing machines, resulting in possibly the most realistic portrayal of the mental disintegration of enlister in war. In ‘A Clockwork Orange’, the character of Alex is a happy-go-lucky rogue who relishes in the interests of sex and violence. But when the government use Alex as the subject for their new brainwashing method, Alex loses his free will and becomes a mechanical organism, fleshy on the outside, but ticking and whirring on the inside, or as the title suggests, ‘a clockwork orange’, causing Alex’s inner-evil to only bubble up deep inside of him. In Kubrick’s 1962 film ‘Lolita’, Humbert Humbert, played by James Mason, struggles to confess his love for the adolescent Lolita. But Humbert’s dark side in the form of Clare Quilty, played by Peter Sellers, does not hesitate, and takes total advantage of the young girl. Carl Jung called this dark side ‘The Shadow’. Kubrick was aware of Jung’s theories and frequently quoted them9, revealing that the themes for his films, and the decision to tell these stories, were highly deliberate. When he originally wrote his article, Truffaut criticized filmmakers who received vast critical acclaim for their rather voiceless and non-unique literature adaptations, as well crafted as they may be. He stated that true auteurs craft stories and themes designed especially for “visual storytelling”10. However, all of Stanley Kubrick’s films were in reality, literature adaptations. So does that exempt Kubrick from this factor of auteur theory? The answer is, of course not. Stanley Kubrick was frequently criticized for in fact straying too far from his original literary source material. The most famous example of such controversy within Kubrick’s portfolio was the film adaptation of Stephen King’s classic horror tale, ‘The Shining’. Stephen King famously disliked the adaptation of his novel, decrying the underplaying of the supernatural elements: “Parts of the film are chilling, charged with a relentlessly claustrophobic terror, but others fall flat. Not that religion has to be involved in horror, but a visceral skeptic such as Kubrick just couldn't grasp the sheer inhuman evil of The Overlook Hotel… What's basically wrong with Kubrick's version of ‘The Shining’ is that it's a film by a man who thinks too much and feels too little; and that's why, for all its virtuoso effects, it never gets you by the throat and hangs on the way real horror should”11. But years after the film was released, it has gained unmitigated infamy as one of the ‘scariest films ever made.’ Kubrick made the story of ‘The Shining’ advance from being a simple haunted house story into a myriad of dark complexities within the human psyche. Kubrick doesn’t talk down to the Still from ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ audience: he makes us use our minds and imaginations to their greatest effect, to create a more horrifying experience that will remain in your mind forever. The initial criticisms of ‘The Shining’ on its original release is a common outlook when experiencing any Kubrick film for the first time. Due to the depth and mystery behind Kubrick’s work, multiple viewings are essential to receive the full effect of his art. When Woody Allen talks about the first time he saw ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, he says, “I didn’t like it and I was very disappointed. And then, three or four months later, I was with some woman in California, and she was telling me what a wonderful film it was. I went to see it again, and I liked it a lot more. Then a couple of years later I saw it again, and thought ‘this is a really sensational movie.’ It was one of the few times in my life where I realized the artist was much ahead of me”12. One of the criticisms of auteur theory is that it collapses “under the reality of the studio system”13, in which the producers and the money men would have final cut of the film and complete control over the artists creative vision. But yet again, using Kubrick as an example, this criticism could be put to the test by looking at the controversy surrounding his 1971 dystopian nightmare, “A Clockwork Orange”. Upon its initial release, it was believed that the violence and youth gang culture depicted in the film was the foundation and influence behind a series of “clockwork killings”. Impressionable teens were so enthralled by Kubrick’s film, that they imitated what they saw on-screen creating one of cinema’s greatest examples of life imitating art. Kubrick received many threatening letters, including death threats for the outrage that his film caused. Fearing for the safety of himself and his family, he withdrew the film from Britain. “A Clockwork Orange” would not be available on either British television or video until Kubrick’s death in 199914. Although the film was phenomenally successful, the British Public would have to wait another 28 years to experience the charm and horror of Alex DeLarge. But one of the interesting aspects behind the fiasco was the studio’s total support behind Kubrick’s decision to withdraw the film from circulation in British theatres. It damaged Warner Bros and Kubrick financially, but according to Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s brother-in-law, “They didn’t care, they just wanted to make more movies with Stanley”15. The support that Warner Bros gave Kubrick is a crucial example of how the power of an auteur such as Kubrick can render the judgment and confidence of a producer or a studio. Stanley Kubrick truly was in charge of every aspect of his films, and was master to even those gave him the money to create his visions. Auteur theory is a study in film that can also be connected to genre theory, for there are numerous auteurs that are identified as working within a specific genre. Famous examples would be John Ford, who worked predominantly within the western genre, or Alfred Hitchcock, who was icon with thrillers. Stanley Kubrick however, was a master with most genres. In a career spanning almost 50 years, Stanley Kubrick had a lot to his name. Steven Spielberg says, “Stanley Kubrick was a chameleon. He never made the same picture twice. Every single picture is a different genre, a different period, a different story a different risk”16. Stanley Kubrick managed to cover war (‘Full Metal Jacket’, ‘Paths Of Glory’), Comedy (‘Dr. Kubrick on the set of ‘A Clockwork Orange’ Strangelove’), Period Drama (‘Barry Lyndon’), Science Fiction (‘2001: A Space Odyssey’), Romance (‘Lolita’), Horror (‘The Shining’), Dystopias (‘A Clockwork Orange’), Historical Drama (‘Spartacus’), Erotic Thriller (‘Eyes Wide Shut’), Crime (‘The Killing’). Although Stanley Kubrick only made 13 films, the wide, intense library of stories and genres he covered, only added mass to his work. It is interesting to note how the audience’s relationship with the director and ‘cult of celebrity’ add to the auteur theory. The way in which the audience strive to see a film because of the name attatched, builds hype to the director’s level of stardom. Alfred Hitchcock became an icon throughout the 1950’s, presenting his television series ‘Alfred Hitchcock Presents’ every week. Television audiences found his exuberant wit and trademark physical features so recognizable and curious, that it developed their thirst to go out and be entertained by an ‘Alfred Hitchcock movie’. Through the early 1960’s, Stanley Kubrick was making a reputation for himself as one of the upcoming, aspiring talents of modern cinema, having directed hit films like ‘The Killing’, ‘Paths Of Glory’, ‘Spartacus’ and ‘Lolita’. Due to Kubrick’s success, when his 1964 black comedy film ‘Dr. Strangelove’ was released, audiences literally lined up around the block to witness the next ‘Stanley Kubrick film’. The controversial subject matter surrounding Kubrick’s films added to the intrigue and the mystery of what he produced for cinemas. The impact of his work saw that almost every poster for every Kubrick film read: ‘Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket’, ‘Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut’, ‘Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove’. One of the major reasons why audiences flocked to see these films was because of those two words above the title. But what were the flaws of Stanley Kubrick? The reason why some disliked his movies was because they weren’t ‘emotionally engaging’. In Martin Scorsese’s film, ‘Raging Bull’, Scorsese rarely invites us into the mindset of Jake La Motta, but rather, holds the audience at arms length and allows us to observe his actions and his relationships, and determines that we make our own judgments on his lifestyle. Stanley Kubrick kept this story-telling method alive through the entirety of his art. Kubrick films were not emotional; they were observations and essays ON emotion. William Friedkin states, “the job of an artist is to reflect society for what it is, that’s what makes Kubrick such an artist”17. Stanley Kubrick merely showed his audience the world through his own eyes, and probably the most challenging aspect of his films were that he asked us to provide our own solutions, as the great artists provided questions, not answers. What made Stanley Kubrick so special was his dedication to change the form of storytelling in cinema and bring it to the next stage of its life. Steven Spielberg talks about a conversation he once had with Kubrick: “He kept saying ‘I want to change the form, I want to make a movie that changes the form’, and I said ‘didn’t you do that with 2001?’ He said ‘just a little bit, but not enough”18. With today’s technology and advanced methods of storytelling, it is unimaginable what Kubrick would’ve created with such equipment and opportunities, for ever since he made ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ back in 1968, he was already light-years ahead of any other story teller. So, how does auteur theory affect the way we interpret cinema in the modern age? Is it something that intensifies audiences experience and education of the form, or like many other film theories, is it merely the foundation of criticism for cinema academics? Whatever it is the auteur theory brings to cinema, it is unquestionably effective in our education and acknowledgment of special artists. Although cinema is undoubtedly a collaborative medium, the contribution of these unique authors and their distinct vision is indeed what makes a film so significant in our culture. And all this can be viewed through the form, and art, of Stanley Kubrick. References: 1) Google Books Retrieved December 1 2012 2) LoBrutto, Vincent (1999). Stanley Kubrick: a Biography. Penguin Books. Retrieved December 1 2012 3) LoBrutto, Vincent (1999). Stanley Kubrick: a Biography. Penguin Books. Retrieved December 1 2012 4) William Freidkin interview, “The Visions Of Stanley Kubrick” Documentary, Retrieved December 1 2012 5) Stanley Kubrick, “Michel Ciment Interviews Stanley Kubrick”, Retrieved December 1 2012 6) Francois Truffaut, ‘Article on Auteur Theory’, Retrieved December 1 2012 7) Interview with Steven Spielberg, “The Haven/Mission Control” Documentary, Retrieved December 1 2012 8) Interview with Stanley Kubrick. Bean, Robin: ‘How I learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Cinema.’ Film and Filming, June 1963, Retrieved December 1 2012 9) Paul Durcan, ‘Stanley Kubrick – The Complete Films’, p.10, Retrieved December 2 2012 10) Francois Truffaut on Auteur Theory, Retrieved December 2 2012 11) Stephen King, "Quoted in". Thewordslinger.com. 2008-03-01. Retrieved December 2 2012 12) Woody Allen on ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, Retrieved December 2 2012 13) Aljean Harmetz, Round up the Usual Suspects, p. 29. Retrieved December 2 2012 14) ‘Stanley Kubrick: A Life In Pictures’ Documentary, Retrieved December 2 2012 15) Interview with Jan Harlan, ‘Stanley Kubrick: A Life In Pictures’ Documentary, Retrieved December 2 2012 16) Interview with Steven Spielberg, ‘Spielberg on Kubrick’, Retrieved December 2 2012 17) Interview with William Friedkin, “The Visions Of Stanley Kubrick” Documentary, Retrieved December 2 2012 18) Interview with Steven Spielberg, ‘Spielberg on Kubrick’, Retrieved December 2 2012