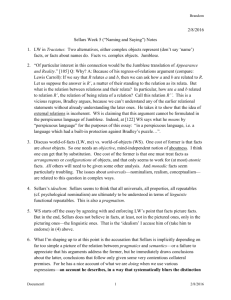

Lecture Notes

advertisement

Brandom 2/9/2016 Sellars Week 2 Notes 1. Introductory comment for IM: WS loved the mystery story form of organizing our peculiar genre of creative nonfiction writing. It contrasts with the journalistic form of organization. In the former, you don’t know what the main thesis that will be defended is until the very end. In the latter, you tell them what you’re going to tell them, tell them, and then tell them what you’ve told them. 2. Roughly, IM introduces crucial elements of an inferentialist semantics, and SRLG introduces crucial elements of a normative pragmatics. 3. Themes for IM: a) Material Inference b) Inference vs. mere association. The difference is in part the normative character of inference, about which more in SRLG (plus account there of language-language transitions). c) Material: Logic, substitution, and form (logical, theological, and geological forms). Bolzano-Frege method for moving from material goodness of inference to logical goodness of inference (need a way to identify logical vocabulary: cf. two classical issues of philosophy of logic). Materially good inferences essentially depend on the occurrence of nonlogical vocabulary. Premises from which to reason vs. Principles in accordance with which to reason. Lewis Carroll, Achilles and the Tortoise point on the side of logic. Its analog for material case. d) Subjunctive conditionals, and what they express. WS’s claim seems to be: need to acknowledge material proprieties of inference in order to underwrite reasoning from counterfactual or subjunctive premises. Q: But why are these different from inferences underwritten simply by contingent regularities? The former can be understood as enthymematic, by supplying so-called (confusingly, in this context) “material” conditionals (that is, two-valued, classical, truth-functional conditionals). Then modus ponens is the only rule of inference. That is formally elegant, but implausible for brutes and children—cf. the attribution of mastery of disjunctive syllogism to dog who sniffs one fork of a road, not finding what he seeks, and immediately, without checking, dashes down the other fork. But the latter can also be understood enthymematically, by supplying a suitable counterfactual conditional. What is the difference that makes a difference between these cases? e) Q: What kind of inferentialism is Sellars endorsing? Candidates include at least weak, strong, and hyper-inferentialism. (The last is ruled out by SRLG’s discussion of language entry and exit transitions.) Document1 1 2/9/2016 Brandom 4. Themes for SRLG: a) Needed: a middle way (via media) between regularism and regulism. Regularism misses out on the norms. Sellars does not explicitly formulate the gerrymandering objection, which is in essence the same as disjunctivitis. But his insistence on the “rulishness” of rules makes it clear that he takes it to be a key criterion of adequacy that we make sense of the possibility of incorrect moves, according to a rule. Mere regularities won’t support that. Furthermore, though again this criterion of adequacy is not explicit, the account must be compatible with arbitrary degrees of incorrectness of actual performance. Millikan’s different version does this (the sperm story, the magnetosome story). So does WS’s: the rule that the teachers had in mind (explicitly represented to themselves when teaching) is what determines correctness. Regulism generates a regress (which Kant had already noticed). b) WS’s idea: need a notion, not just of pattern-governed behavior, which Millikan develops much more thoroughly. Need also a notion where a representation of the rule plays a causal role in producing the regularity. So WS really has four kinds of behavior in his botanization: i. Merely regular (patterned) ii. Pattern-governed iii. Pattern-governed with a representation of the rule playing a causal role, mediating between antecedent pattern and subsequent pattern iv. Rule governed c) Sellars’s middle way, his solution to the challenge he has set, is diachronic, and social. (Think Hegel.) d) Language-language transitions, language entry transitions, and language exit transitions. Why this does not commit WS (as McD complains that it does) to seeing an outer boundary to the conceptual: transitions are just from something that is not the taking up of a position in the game to something that is. No further commitments regarding the nature of what is not itself the taking up of a position in the game are needed for this botanization. 5. Beginning of SRLG: It seems plausible to say that a language is a system of expressions, the use of which is subject to certain rules. It would seem, thus, that learning to use a language is learning to obey the rules for the use of its expressions. However, taken as it stands, this thesis is subject to an obvious and devastating objection. The objection is that taking 'correct' to mean 'correct according to a rule' generates a familiar sort of regress: The refutation runs as follows: Thesis. Learning to use a language (L) is learning to obey the rules of L. But, a rule which enjoins the doing of an action (A) is a sentence in a language which contains an expression for A. Hence, a rule which enjoins the using of a linguistic expression (E) is a sentence in a language which contains an expression for E--in other words, a sentence in a metalanguage. Consequently, learning to obey the rules for L presupposes the ability to use the Document1 2 2/9/2016 Brandom metalanguage (ML) in which the rules for L are formulated. So that, learning to use a language (L) presupposes having learned to use a metalanguage (ML). And by the same token, having learned to use ML presupposes having learned to use a metametalanguage (MML) and so on But, this is impossible (a vicious regress). Therefore, the thesis is absurd and must be rejected. The metalanguage expresses rules for the proper application of concepts of the object language. But these rules, too, must be applied. So the metametalanguage expresses rules for applying the rules of the metalanguage, and so on. If any talk is to be possible, there must be some meta...metalevel at which one has an understanding of rules that does not consist in offering another interpretation of them (according to rules formulated in a metalanguage), but which consists in being able to distinguish correct applications of the rule in practice. The question is how to understand such practical normative know-how. Although he, like Wittgenstein, uses 'rule' more broadly than is here recommended, Sellars is clearly after such a notion of norms implicit in practice: We saw that a rule, properly speaking, isn't a rule unless it lives in behavior, rule-regulated behavior, even rule-violating behavior. Linguistically we always operate within a framework of living rules. (The snake which sheds one skin lives within another.) In attempting to grasp rules as rules from without, we are trying to have our cake and eat it. To describe rules is to describe the skeletons of rules. A rule is lived, not described. 6. Kant's acknowledgement of the possibility of a regress of rules appears in his discussion of the faculty of judgment [Urteilskraft]: If understanding in general is to viewed as the faculty of rules, judgment will be the faculty of subsuming under rules; that is, of distinguishing whether something does or does not stand under a given rule (casus datae legis). General logic contains and can contain no rules for judgment...If it sought to give general instructions how we are to subsume under these rules, that is, to distinguish whether something does or does not come under them, that could only be by means of another rule. This in turn, for the very reason that it is a rule, again demands guidance from judgment. And thus it appears that, though understanding is capable of being instructed, and of being equipped with rules, judgment is a peculiar talent which can be practised only, and cannot be taught. [Critique of Pure Reason, A132, B171.] The regress of rules argument is here explicitly acknowledged, and the conclusion drawn that there must be some more practical capacity to distinguish correct from incorrect, at least in the case of applying rules. Very little is made of this point in the first two Critiques, however. Kant's own development of this appreciation of the fundamental character of this faculty of acknowledging norms implicit in the practice of applying explicit rules, in the third Critique, has an immense significance for Hegel's pragmatism, but only his formulation of the issue seems to have influenced Wittgenstein's. 7. In discussing SRLG: a) Discuss what Millikan made of §§12-16. b) Introduce regulism and regularism, with their dual problems: the regress of regulism, and the loss of norms of regularism, showing up with the gerrymandering problem (“disjunctivitis”). c) Language-entry transitions, language-exit transitions, and language-language transitions (moves). d) In §§25-26, “auxiliary positions” are free positions, which can properly be occupied at any time, without having either moved there by inference, or gotten there by an Document1 3 2/9/2016 Brandom observational language-entry transition. “We note a certain equivalence between auxiliary positions and moves.” Since auxiliary positions can license moves. Q: It is a very strong claim, not argued for here but apparently endorsed, that all auxiliary positions are equivalent to moves. Sellars’s example is “All A is B,” which fits his paradigm. But isn’t Quine’s “There have been black dogs,” also an auxiliary position? And if so, and the claim is that it licenses moves, then surely so does “There is a black dog,” and, indeed, any claim. This is a semantic inferentialist position. Q2: Is that position ever endorsed in IM? e) “We also notice that while it is conceivable that a language game might dispense with auxiliary positions altogether [BB: of the “All As are Bs” sort, perhaps. But also of the “There have been black dogs” sort? Not according to a default-and-challenge understanding of positive justificatory status or entitlement.], although at the cost of multiplying moves, it is not conceivable that moves be completely dispenses with in favor of auxiliary positions. A game without moves is Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark indeed!” Here is the Lewis Carroll “Achilles and the Tortoise” point extended from logic to material inferences licensed by positions. Document1 4 2/9/2016