Lore Hühn and Philipp Schwab (eds.), Die Philosophie des

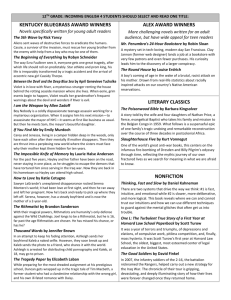

advertisement

Lore Hühn and Philipp Schwab (eds.), Die Philosophie des Tragischen: Schopenhauer – Schelling – Nietzsche (Proceedings of a symposium held May 21-24, 2008 at Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, Freiburg). Berlin and Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2011. x + 678pp. ISBN 978-3110209181. Cloth, $150.00. In advocating what he himself called a philosophy of “Dionysian pessimism,” Nietzsche explicitly situated himself in the modern, in particular German tradition of philosophical pessimism (cf. e.g. M P 3-4; FW V, 357). At the same time, however, he distanced himself from this very tradition, by returning to the tragic worldview of the ancient Greeks, who were able to come to terms with the suffering in life, and thereby, to overcome the pessimist outlook as such (cf. e.g. BT ‘Self-Criticism’, 1-7; EH ‘BT’, 1-4). In this volume, both of these contrasting claims are examined from different angles by bringing Nietzsche, alongside Schelling and Schopenhauer, into the debate on the meaning and role of tragedy in modernity. A few considerations by more contemporary thinkers serve as starting and guiding points for doing so. First, the suggestion of Herbert Marcuse, who held that the conception of the tragic as “meaningless suffering” is typically and exclusively modern. Secondly, the claim of Peter Szondi that it is essentially a typical German conception. Thirdly, the suggestion of Botho Strauß, who argued that the occident culture is founded on the sacrifice of the ever returning scapegoat, inherent in the original meaning of τραγῳδία (“lamentation song for a sacrificed goat”), but denied in the contemporary age. On the basis of these considerations, the different chapters deal with questions like: what was exactly the role of tragedy in antiquity? Did the Greeks indeed have a tragic philosophy, based on the conviction that all life is tragic? Can such a philosophy be conceived in modern thought, influenced as it is by seemingly anti-tragic, Christian notions like reconciliation and redemption? To what extent can the modern philosophies of Schelling, Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, respectively, be considered as philosophies of the tragic indeed? And above all, how do these modern philosophies relate to the ancient conception of the tragic, as well as to one another? In the introduction, the editors of the volume, Lore Hühn and Philipp Schwab, point to the problematic relation between the modern self-understanding and the ancient understanding of the tragic. Initially, the tragic had become incomprehensible in modernity, they argue, partly because of the centrality of notions like reconciliation and redemption in Christian thought. Nevertheless, the consciousness of the tragic has gradually descended into the modern mindset again, mainly through a movement of resistance against the optimistic stress on autonomy and progress in Enlightenment thought. Following Szondi, they argue that the tragic notions of negativity, self-rupture and contradiction constitute the background model of the speculative dialectics of Hegel and Schelling. In addition, they argue, the negative aspect of the tragic is intensified in the nihilistic philosophies of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, in which the tragic is understood in a typically modern sense as meaningless suffering, like Marcuse argued. The twenty-eight chapters are structured on the basis of this central account and accordingly divided into the following five parts: “I. Configurations of the Tragic”; “II. The Tragic in Antiquity”; “III. The Tragic in the Philosophy of German Idealism”; “IV. The Tragic between Schopenhauer and Nietzsche”; “V. Nietzsche and the Tragic in Modernity”. Nietzsche’s name is mentioned in almost all of the twenty-eight chapters, as can be discerned from the helpful index of persons, which is included at the end of the book (next to a list of authors and an index of “literary figures and mythological characters”). However, about thirteen chapters are primarily dedicated to Nietzsche, sometimes in relation to other philosophers, like Schelling and Schopenhauer. Obviously, it will be impossible to offer a general characterization of the different chapters, nor will it be possible to give a separate summary or critique of each individual chapter (see pp. 11-16). Instead, I will point out some particular points of interest in the chapters that directly deal with Nietzsche, and conclude with a note on the use of the volume as a whole. 1 *** The first part of the volume consists of four, more general and contemporary reflections on tragedy in relation to dialectics, negativity, philosophy and politics, respectively. The second part deals with the role and meaning of the tragic in Antiquity, especially in relation to Aristotle’s later interpretation of the tragedy. Only in the third part, which mainly deals with Schelling’s conception of the tragic, there is one chapter, by Damir Barbarić, which offers a “provisional outlook” on the relation between Nietzsche’s and Schelling’s conception of Dionysus. Barbarić argues that, although their similar distinction between the Apollonian and the Dionysian is too striking to be coincidental, their conception of the figure of Dionysus differs with regard to their assessment of its importance, its orgiastic character and its desirability. The remaining two parts, which make up more than half of the book, are largely dedicated to Nietzsche’s philosophy of the tragic and its relation to Schopenhauer’s view of the tragic. In the translated and already famous text of Martha C. Nussbaum, “Nietzsche, Schopenhauer and Dionysus,” she argues, with the help of Nietzsche’s later writings, that he, in The Birth of Tragedy, deliberately used Schopenhauerian categories to undermine the latter’s view on art and tragedy with his own conception of Dionysian tragic art. In contrast to this, in her chapter, “The Tragic – Quietive or Motive of Life? Nietzsche contra Schopenhauer,” Barbara Neymeyr rightly points out that, according to the later Nietzsche, it were exactly the Schopenhauerian, as well as Kantian categories which distorted his preliminary and undeveloped views in The Birth of Tragedy (BT P, 6). Partly because of this distortion, but also because of Nietzsche’s later caricatures and oversimplifications of Schopenhauer’s views, the precise relation between their views on tragedy is hard to discern, as also Nussbaum herself notes in her chapter. The relation is more elaborately and more accurately illuminated, however, by two chapters of Brigitte Scheer and Markus Scheffler, which discuss Schopenhauer’s view of the tragic, in combination with the chapter of Neymeyr, which illuminates its relation with Nietzsche’s views. Finally, in an original, but more difficult to read chapter, at the end of the fourth part, entitled “Passionate Individuality. On the Tragic Condition of Intensified Life in Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Camus,” Asmus Trautsch focuses on the central function of individual passionateness in the failing of the tragic hero. It is remarkable that the penultimate chapter of the fifth part, by Domenico M. Fazio, entitled “A Conception of the Tragic ‘for Private Use’. Julias Bahnsen writes Friedrich Nietzsche,” has not been included in the fourth part as well, since it also deals with a conception of the tragic that literally lies “between Schopenhauer and Nietzsche.” The chapter first gives an interesting account of Bahnsen’s Schopenhauerian philosophy of “real dialectics,” including his conception of the tragic as a fundamental self-contradiction of the will. Subsequently, on the basis of Bahnsen’s letter to Nietzsche in 1878, to which Nietzsche never replied, this “metaphysical” and “practical” conception is confronted with Nietzsche’s “aesthetic” understanding of the tragic in The Birth of Tragedy. The fifth part starts with a challenging reflection, by Günter Figal, on the issue: “Is Life Tragic? Reflections on Plato and Nietzsche.” He argues that the ancient Greeks in general, and Plato in particular, could not conceive of life as being tragic in itself, independent from the art form of the tragedy, since the meaning of the adjective τραγικός was inherently connected with the tragedy play as performed in the theatre. Also Nietzsche’s employment of the term in his construction of a “tragic philosophy” goes back to this artistic usage, and without this context, Figal argues, the term becomes impossible to define. Figal’s position raises, amongst others, three issues which are touched upon in the subsequent chapters: first, it implies that the attempt to construct a tragic philosophy, based on the conviction that life in itself is tragic, can only be of modern origin, as also Szondi has claimed. This 2 would seem to go against Nietzsche’s position, who especially in his early lectures on “Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks,” actively sought for points of connection between the ancient Greek and the modern German culture, in order to advance the return of tragic culture, as Günter Zöller points out in the subsequent article, entitled “Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Germans. Nietzsche’s Antiquity Project.” In contrast to this, however, it could be argued that the later Nietzsche might have been aware of being the first to construct a philosophy of the tragic, in presenting himself as the “first tragic philosopher” (EH ‘BT’, 3), as some of the following chapters point out. Figal’s position implies, secondly, that it is impossible to define the tragic in a general and conceptual way, independent from a particular artistic representation in the artwork of the tragedy. In a translated piece from his On Germans and Other Greeks. Tragedy and Ethical Life (Bloomington, 2001), entitled “Nietzsche and the Rebirth of the Tragedy,” Dennis J. Schmidt argues that this is exactly the reason why Nietzsche considered his The Birth of Tragedy to be failed. The tragic experience of art can never be grasped in the conceptual and propositional language of metaphysics. This is the reason why the later Nietzsche concludes, retrospectively, that the author of The Birth of Tragedy “ought to have sung, this ‘new soul’, and not spoken [reden]!” (BT ‘Self-Criticism’, 3). A third issue which Figal’s chapter raises, is the question of how Nietzsche’s early conception of the tragic in The Birth of Tragedy, with its concrete references to ancient tragedy, relate to his later attempt to construct a philosophy of the tragic, independent from these concrete references to the artwork of the tragedy. In the two subsequent chapters, both of which are translated from English as well, the relation between The Birth of Tragedy and Nietzsche’s later work is once again examined. In the chapter “Making Life Worth Living: Nietzsche on Art in The Birth of Tragedy,” from his Making Sense of Nietzsche: Reflections Timely and Untimely (University of Illinois Press, 1995), Schacht is primarily concerned with demonstrating that Nietzsche’s understanding of art did not fundamentally change after The Birth of Tragedy, remarkably enough, almost without referring to any of the later writings themselves. Also Janaway holds, in his “Beauty is False, Truth Ugly: Nietzsche on Art and Life,” that the relation between art and truth remains fundamentally the same throughout Nietzsche’s writings. Against in particular Bernard Reginster’s claim that in The Birth of Tragedy, art only redeems from the truth in so far as it creates protective illusions, Janaway argues that art, throughout all of Nietzsche’s writings, also serves to learn to live with the tragic truth and to affirm it. The prevailing preoccupation with The Birth of Tragedy in the secondary literature is somewhat remarkable in light of Nietzsche’s later remark that it is an “impossible book,” and a badly written one as well (BT ‘Self-Criticism’, 3), as Andreas Urs Sommer points out in his chapter, entitled “The Tragic in Nietzsche’s Later Work.” In contrast to this, he turns to Nietzsche’s final year of writing, 1888, and to his reconsideration of The Birth of Tragedy in his Ecce Homo, in order to answer the question to what extent he can be considered as a tragic philosopher indeed. Sommer notes that the late Nietzsche refrains from giving any concrete reference to ancient tragedy and instead, turns to the “psychology of the tragic artist,” in order to instrumentalize the tragedy in his philosophy of lifeaffirmation. Within his later philosophy of affirmation, however, the meaning of the tragic tends to be simplified, dedifferentiated, and to be annulled. In taking up the unbearable challenge to affirm tragic existence as valuable in itself, Nietzsche’s philosophy of the tragic has become tragic itself, Sommer concludes with reference to the analogy which Nietzsche himself observed between a donkey and a philosopher: “Can an ass be tragic? – Can someone be destroyed by a weight he cannot carry or throw off? . . . The case of the philosopher” (TI ‘Arrows and Epigrams’, 11). In a lengthy chapter, entitled “The Tragic Overcoming of Nihilism. Nietzsche’s ‘Philosophy of the Tragic’ from The Birth of Tragedy to the later Work,” Philipp Schwab tries to bring everything together, by giving an overview of the development of Nietzsche’s view of the tragic throughout his 3 writings. Schwab aims to demonstrate that, from The Birth of Tragedy onwards, there is a plural conception of the tragic at work in Nietzsche, which undergoes a threefold process of transformation. First, in The Birth of Tragedy, the tragic consists in the pessimist truth of the futility of being, which can be overcome by way of the (interplay between the) Apollonian illusion, on the one hand, and the merging with the Dionysian will, on the other hand. Secondly, in the middle work (especially the Nachlass), the tragic consists in the most extreme form of (epistemological) nihilism, namely in the tragic knowledge that there is no truth. Thirdly, in a final period, this nihilism is “tragically overcome,” by an affirmation of the nihilistic insight itself – the tragic insight that there is no absolute truth. In this sense, the early, affirmative notion of the tragic returns in Nietzsche’s later works, but in a fundamentally transformed way, Schwab concludes. The final chapter of Mirko Wischke, entitled “The Fiction [Dichtung] of Truth. Nietzsche’s Tragic Worldview in the Context of his Conception of Language,” connects Nietzsche’s conception of the tragic to the nihilistic insight that there is no absolute truth or value as well. The philosopher, he argues, can avoid the threat of nihilism, by revaluing current value-judgments and creating new illusions by way of verbal imageries (Sprachbilder). Wischke’s reading of Nietzsche’s writings and notes is so scattered, however, that his account must be situated on the level of constructing, compiling or even creating a Nietzschean philosophy of the tragic, instead of interpreting it. *** In the end, then, this volume does not so much offer definite answers to the most important questions that are raised in it, in particular by Figal and Sommer, namely: to what extent does Nietzsche succeed in constructing a philosophy of the tragic? To what extent is a modern, post-Christian philosophy of the tragic possible and to what extent is such a philosophy of the tragic conceivable at all? Is life still tragic when it is accepted as such, maybe even affirmed as desirable or valuable in itself, like Nietzsche aims to do? Does not the tragic element disappear, as soon as an answer or a solution has been given to the question of how to deal with the tragic of life, in a similar way as happens with the Christian response to the tragic, as Sommer suggests (562)? For sure, Nietzsche presents the affirmation of tragic suffering as a future ideal and in this sense, as long as it has not been fully affirmed yet, the suffering in life can still be conceived as tragic. But within the ideal of affirmation itself, the tragic seems to be annulled indeed. In addition, the question could be raised whether not the tragic already vanishes as soon as it is determined and mediated with fixed philosophical concepts, as Figal (450), but also Schmidt suggest (474, 494f.)? If this is the case, the tragic would be a matter of immediate experience, which can only be represented in artworks, like music and tragedy plays, and it would merely belong to the sphere of aesthetics and religion, rather than to the domain of philosophy. However, as it is exactly the task of philosophy to determine to what extent and in what way the tragic can be defined and represented, this volume provides a major contribution to the endeavor to do so. The editors of this volume have made a fine selection for this purpose, of suitable and in general very qualitative chapters, which are edited, moreover, in an excellent way. A glance at the initial program of the conference betrays that some of the original contributions have been omitted, while others are translated and/or additionally included. To the extent that this is done in order to ensure the quality, as well as the thematic and linguistic unity of the whole, this can only be applauded. Whereas the reader might be overwhelmed, initially, by the great amount of chapters and the more than 600 pages which are once again added to the ever increasing literature on the topic, the volume as a whole will undoubtedly proof itself to be a valuable source of inspiration and reflection, eventually. Wolter Hartog, Leuven University & Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) wolterhartog@hotmail.com 4