friends of the planetarium newsletter - march 2011

FRIENDS OF THE PLANETARIUM NEWSLETTER – MARCH 2011

Greetings to you all. Saturn will dominate the night sky for the next few months. It appears in the eastern sky at dusk, close to the star Spica. Spica is the brightest star in the constellation of Virgo but Saturn outshines it by over half a magnitude. Saturn will be brighter and to the left of Spica as seen from New Zealand.

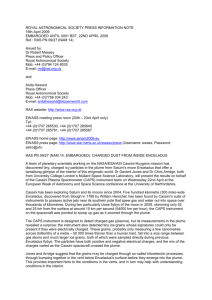

Astronomers worldwide watched in amazement late last year as a huge storm began brewing in Saturn’s upper atmosphere. By January the storm had spread through a large region of Saturn’s north tropical zone.

This disturbance is easily the brightest feature on the globe; it even rivals the brightness of the planet's ring system. The storm is easily visible in large amateur telescopes but the Cassini spacecraft has a ringside seat. Pardon the pun. Here is a recent view of the storm from Cassini. The main part of the system is bigger than the entire planet Earth. It has been dubbed the serpent storm, so named because it appears to snake its way around what is currently about 100 degrees of longitude across Saturn's northern hemisphere. On

Saturn that's at least 160,000 kilometers in length.

Not to be outdone, some of Saturn’s moons are putting on their own show. As spring continues to unfold at Saturn, April showers on the planet's largest moon, Titan, have brought methane rain to its equatorial deserts. This is the first time scientists have obtained current evidence of rain soaking

Titan's surface at low latitudes. Extensive rain from large cloud systems, spotted by Cassini's cameras in late 2010, has apparently darkened the surface of the moon. The best explanation is these areas remained wet after methane rainstorms. Clouds on Titan are formed of methane as part of an Earthlike cycle that uses methane instead of water. On Titan, methane fills lakes on the surface, saturates clouds in the atmosphere, and falls as rain. Though there is evidence that liquids have flowed on the surface at Titan's equator in the past, liquid hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane, had only been observed on the surface in lakes at polar latitudes. The vast expanses of dunes that dominate

Titan's equatorial regions require a predominantly arid climate. Scientists suspected that clouds might appear at Titan's equatorial latitudes as spring in the northern hemisphere progressed. But they were not sure if dry channels previously observed were cut by seasonal rains or remained from an earlier, wetter climate. They concluded this These latest observations have led scientists to conclude that the change in brightness is most likely the result of surface wetting by methane rain, suggesting that recent weather on Titan is similar to that over Earth's tropics. On Earth, the tropical bands of rain clouds shift slightly with the seasons but are present within the tropics year-round. On

Titan, such extensive bands of clouds may only be prevalent in the tropics near the equinoxes and move to much higher latitudes as the planet approaches the solstices.

Here is the latest family portrait showing Titan,

Enceladus and Pandora. Saturn's ice-shrouded moon Enceladus is pumping out more heat from its southern pole than all the hot springs at

Yellowstone National Park in the US, and scientists are at a loss to explain it. The prodigious outpouring of energy significantly boosts the likelihood that an ocean of liquid is sealed beneath the moon's icy surface. Water, in turn, is considered a key ingredient for life. The new data isn't enough to nail down how large an ocean might exist on Enceladus, or its location beneath the ice. It does, however, make computer models hard to explain if Enceladus lacks liquid water. For a long time, scientists thought tidal interactions with neighbor satellites and Saturn would account for about

1.1 gigawatts of energy pumping out of

Enceladus. Heat from the natural decay of radioactive materials inside the moon would add another

0.3 gigawatts. New research from the Cassini spacecraft, however, shows that Enceladus is giving off closer 14 gigawatts. Scientists theorize Enceladus' excess heat may be because the moon used to be in a different orbit that generated a fiercer gravitational tug-of-war with neighboring moons. Energy that built up in the past may be being released now. No matter what the cause, the realization that the icy moon is pumping out as much heat as 20 coal-fired powered plants has scientists thinking.

Just imagine the frustration of Gian Domenico Cassini after discovering Saturn's Iapetus in 1671. He saw the moon just fine whenever it was west of the planet, but on the eastern side it was a no show.

Cassini finally puzzled it out in 1705: Iapetus must be very bright on one hemisphere (the side facing forward in its orbit) and very dark on the other. It took another two centuries to figure out how this two-faced personality came about. The moon's topmost layer of ice has apparently sublimated

(vaporized) away, leaving behind a thick coating of carbon-rich dregs. However, in solving one mystery about Iapetus, Cassini scientists were confronted with another: a towering, mountainous ridge up to 15 km high that stretches along the moon's equator for more than 1,300 km, a third of the way around its circumference. This remarkable and apparently ancient ridge can't be explained by geologic processes. It's had planetary scientists baffled since its discovery. There's yet another vexing problem. Iapetus rotates in lockstep with its 79-day orbit around Saturn, long ago forced into synchrony by Saturn's gravity (just as the Moon synchronously spins and revolves around Earth). But

Cassini's close-ups prove that Iapetus is distinctly out of round. Its overall shape implies that it must have become frozen while spinning quite fast, once every 16 hours. Saturn might be massive, but

Iapetus is so far away that the planet's tidal tugs would take an estimated 10 billion years to slow down such a rapid spin. New research and computer simulations indicate that a massive collision between Iapetus and another rogue moon resulted in the current bizarre properties exhibited by

Iapetus.

The team responsible for Friends of the Planetarium are volunteers from the Hawkes Bay

Astronomical Society (HBAS). Team members have recently changed and it appears that many if not all of last year’s receipts were not sent out. They are enclosed with our apologies.

In upcoming events, the HBAS is honoured to be hosting this year’s annual conference of the Royal

Astronomical Society of New Zealand. The dates are May 27 – 29 and the venue is the War Memorial

Conference center. Special guests are Dr. Fred Watson, Astronomer-in-Charge of the Australian

Astronomical Observatory and David Malin, world-renowned astrophotographer. Members of the public are welcome to register. Visit the HBAS website for details or contact the Planetarium.