Perspectives on EU Competition Policy

advertisement

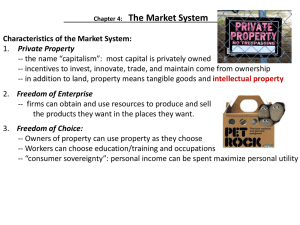

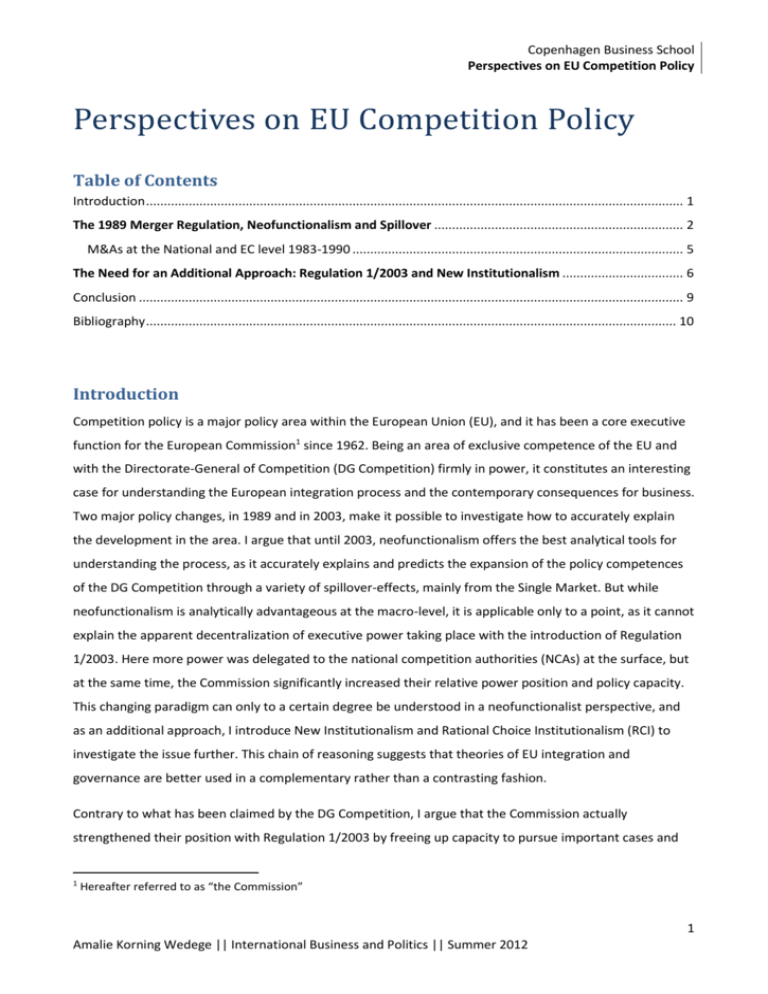

Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy Perspectives on EU Competition Policy Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 The 1989 Merger Regulation, Neofunctionalism and Spillover ...................................................................... 2 M&As at the National and EC level 1983-1990 ............................................................................................. 5 The Need for an Additional Approach: Regulation 1/2003 and New Institutionalism .................................. 6 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................................... 10 Introduction Competition policy is a major policy area within the European Union (EU), and it has been a core executive function for the European Commission1 since 1962. Being an area of exclusive competence of the EU and with the Directorate-General of Competition (DG Competition) firmly in power, it constitutes an interesting case for understanding the European integration process and the contemporary consequences for business. Two major policy changes, in 1989 and in 2003, make it possible to investigate how to accurately explain the development in the area. I argue that until 2003, neofunctionalism offers the best analytical tools for understanding the process, as it accurately explains and predicts the expansion of the policy competences of the DG Competition through a variety of spillover-effects, mainly from the Single Market. But while neofunctionalism is analytically advantageous at the macro-level, it is applicable only to a point, as it cannot explain the apparent decentralization of executive power taking place with the introduction of Regulation 1/2003. Here more power was delegated to the national competition authorities (NCAs) at the surface, but at the same time, the Commission significantly increased their relative power position and policy capacity. This changing paradigm can only to a certain degree be understood in a neofunctionalist perspective, and as an additional approach, I introduce New Institutionalism and Rational Choice Institutionalism (RCI) to investigate the issue further. This chain of reasoning suggests that theories of EU integration and governance are better used in a complementary rather than a contrasting fashion. Contrary to what has been claimed by the DG Competition, I argue that the Commission actually strengthened their position with Regulation 1/2003 by freeing up capacity to pursue important cases and 1 Hereafter referred to as “the Commission” 1 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy cartels, while still imposing rules making it possible for them to counteract national competition authorities’ decisions “through the back door”. Thus, we cannot understand the European integration process merely by applying one set of analytical tools with one area of focus, and a thorough comprehension requires that the theories are integrated to shed light on all the relative perspectives. Also, the changes in competition policy seriously affect the conditions for especially transnational corporations and companies in the EU in regard to business opportunities for Mergers and Acquisitions (M&As) and other agreements, and thus we can ask the question: How can we understand the major policy changes in EU competition policy, and what are the consequences for business? The 1989 Merger Regulation, Neofunctionalism and Spillover In order to understand how a theoretical addition to neofunctionalism was made necessary by the 2003 policy change, an understanding of why and how neofunctionalism accurately can describe the process of integration in the EU competition policy area until 2003, must be presented. The early neofunctionalist approach to European integration drew heavily on the work of Mitrany, Monnet and Haas (Bache, George & Bulmer 2011 p. 5ff) and it adopted a pluralist approach to explain why in the post-war era, the European nation states voluntarily surrendered sovereignty. Haas saw the driving force of integration as nothing less but the “calculated self-interest of political elites” (Bache et al. 2011, p. 10) which through a variety of spillover-effects would advance European integration. The concept of spillover arose when national governments in pluralistic political processes, which involved interest groups as well as bureaucratic actors, took the first steps towards integrating the economy. Once this had happened, a variety of spillover-effects would further integration. Functional spillover would arise because of the interconnectedness of modern economies which would prompt technical pressures to integrate more sectors, in order to achieve the original goal, which would in turn press for integration of more related sectors etc. Perhaps more importantly, political spillover would be driven by interest groups of newly integrated sectors, who would need to address their lobbying to Brussels and the supranational institutions concerned, instead of national governments. Once the interest groups came to appreciate the new possibilities for lobbying, they would press for political integration of related sectors. Thus the interest groups become advocates for further integration, as well as they formed an effective barrier against retrenchment from national governments. Neofunctionalism also speculated in “cultivated spillover” where 2 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy the Commission2 was said to cultivate contacts and transnational networks to add additional pressure on national governments for more integration. (Bache et al. 2011, p. 8ff) Neofunctionalism thus concluded that the integration process evolved unintentionally after the initial steps were made, undermining the political power of national governments. This statement does not, of course, stand without criticism, as the supranational/intergovernmentalist debate continues with empirical evidence pointing in different directions, depending on the policy area described. Indeed national governments do have power, which is evidenced by e.g. the slowing of the integration process in the 1960s and 70s and in particular the Empty Chair Crisis in 1965-66. (Gravier 2012, lecture 1) Neofunctionalism as a purely deterministic theory therefore is not very useful, as the integration process obviously is subject to other mechanisms than spillover. However, it does offer some of the best analytical tools for understanding a wide range of changes in major policy areas of the EU, as we otherwise cannot explain how the integration process, as in the case of competition policy and especially the 1989 Merger Regulation, went against the specific wishes of the member states, as shall be discussed below. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) In regard to competition policy, neofunctionalism sees it as primarily a spillover from the Single Market, and thus it was first completed after the adoption of the Single European Act (SEA) which came into effect in July 1987. (Bache et al. 2011, p. 596) Promptly the Merger Control Regulation (MCR) was adopted in 1989 after 16 years of negotiations (Buch-Hansen, lecture 10), and I will show that neofunctionalism effectively explains this development through a process of functional and political spillover, but the earlier history of EU competition policy also deserves notice: Competition policy has been called the “first common policy of the EC/EU” (Bache 2011, p. 359) and it was part of the Treaty of the European Coal and Steel Community 1951 (ECSC). It was, however, originally initiated by US officials and implemented through the Marshall Plan, and was thus originally a result of ordoliberal ideas, as well as the Frenchs’ belief that preventing cartels and collaborative business practice could keep Germany decentralised. Thus competition policy was not a key interest of the nation states in the ECSC. (Buch-Hansen 2009, p. 257) The pillars of EU competition policy originally consisted of articles prohibiting cartels & anticompetitive agreements (Art. 1013), abuse of dominant market positions (Art. 102), state aid (Art. 107) and also imposed obligations to privatize public companies (Art. 106). Regulation on M&As was not included and it was dealt with in national legislation from the 1970s. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) The enforcement was made possible through Council Regulation 17 in 1962 (Regulation 17/62) which gave the DG Competition extensive powers to investigate, prosecute, judge and impose fines for 2 In this paper, the Commission is seen as representing the interests of the Community, as well as the Council is seen as representing the interests of the member states, as is the common paradigm. 3 All article references refer to the TFEU unless otherwise indicated 3 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy anticompetitive behaviour. It established a prenotification system where exemptions to Art. 101 and 102 could be granted if agreements fell under Art. 101(3), stating that anticompetitive agreements could be undertaken under conditions of e.g. “technical or economic progress”. (Art. 101(3) Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10).Thus companies could obtain legal security for their agreements by notifying the Commission, which lead to a massive case-overload for the DG in the 1960s and 70s. This resulted in the so-called “block exemptions” where certain agreements were preapproved if they fell under a specific preexisting ruling, and EU lawyers become very adept at writing agreements which just fitted into the existing block exemptions. (Ruttley 2003) There was stagnation in the competition policy area until the late 1980s where the DG Competition finally managed to expand their policy competence to include Mergers and Acquisitions (a long-standing wish of the Commission) after failed attempts to reach agreements in 1973, 1982, 1984, 1986 and 1987, because of strong national opposition. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) Several issues can be raised about this policy development. First and foremost it must be asked why a spillover effect to integrate more sector was not observed after the adoption of the first treaty, as several related sectors immediately comes to mind, especially the establishment of industrial policies relating to M&As at the European level instead of the national level. (Buch-Hansen 2009, p. 259) Why did a spillovereffect not arise to integrate national legislation on M&As into EU competition policy? Firstly, according to neofunctionalism, political spillover arose if, and only if, interest group and political elites saw integration as the more preferable alternative in their “calculated self-interest”. Secondly, functional spillover would only occur if technical pressures within industries and sectors made the original policy goal unobtainable without further integration. But Regulation 17/62 gave European companies (or corporate lobby groups) a unique legal security for agreements, despite the fact that the Commission often took long to deliver a verdict. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture) But by writing agreements to fit into the existing block exemptions, there was simply no incentive for companies to lobby for further integration, as M&As primarily were national at the time. If there are no interest groups prompting integration (because of Regulation 17/62), there is no political spillover, and if the sector is functional as it is (because of the nature of M&As at the time) there is no functional spillover. The “cultivated spillover” of the Commission in 1973, 1982, 1984, 1986 and 1987 thus proved insufficient to enhance integration, and correspondingly, the development of EU competition policies in the 1960s and 70s confirms the working logic of neofunctionalism. However, two major events in 1987 changed the conditions for European businesses fundamentally. The 1987 SEA establishing the Single Market gave rise to a transformation of the business community itself (Buch-Hansen 2009, p. 260) with an explosion in the number of M&As taking place at the European level, while M&As at the national level remained relatively constant, as seen on figure 1. 4 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy M&As at the National and EC level 1983-1990 300 250 200 150 100 EC level National Level 50 0 Source: Buch-Hansen 2009 p. 169, Based on data from Commission (1985b, 1988, 1989, 1992), data collected by the Commission) The rising number of M&As regulated by multi-jurisdictional authorities resulted in heavy lobbying from transnational business groups for what was called a “one-stop-shop” where companies would only need to operate with one set of regulations, instead of several national sets of regulations. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) This constituted substantial political pressure which resulted in a political spillover. The second event in 1987 that made the MCR desirable was the Phillip Morris case, where the European Court of Justice (ECJ) by their ruling expanded the scope of the community’s power, by stating that the authority to prevent market domination could be inferred from other articles of the existing treaties than those already described. (Bache et al, p. 359f) This created major uncertainty amongst national- and transnational businesses alike, which prompted technical pressures to integrate all sectors of competition policy under Regulation 17/62. Firms began to notify their M&As to the DG Competition voluntarily, essentially resulting in a functional spillover which together with aforementioned political spillover resulted in the 1989 MCR. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) EU competition policy in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s can thus be accurately described by the analytical tools offered by neofunctionalism, with a specific focus on the various effects of spillover. But also the essential premise, that in sectors where national governments oppose integration, the pluralist process of modern politics can create integration anyway, stands, as evidenced by the 1989 MCR. This constitutes a powerful argument in the theoretical dichotomy between supranationalism and intergovernmentalism, but as we 5 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy shall see, development in the Competition Policy Area requires that neofunctionalism, with all of its strengths, must be accompanied by other theories to accurately describe the policy process of competition policy after 2003. The Need for an Additional Approach: Regulation 1/2003 and New Institutionalism The adoption of the EC Council Regulation 1/2003, which took effect on the 1st of May 2004 (Ruttley 2003), has been described as the most radical policy change in the history of EU competition policy4. (Wigger & Nölke 2007, p. 488) And indeed, both procedural and substantial changes were undertaken, fundamentally challenging the way EU competition policy has been perceived so far in this paper. To show how this requires a new understanding of the power relations between the Commission and the national governments, the changes will be described and correspondingly analysed within the framework of New Institutionalism and Rational Choice Institutionalism and in particular the Principal-Agent model. With the replacement of Regulation 17/62, the Commission effectively abolished the Prenotification system and made companies solely responsible for assessing whether their agreements were in conflict with Art. 101 and 102, and correspondingly whether Art. 101 (3) grants exemption. (Wigger & Nölke 2007, p. 496) This change has raised considerable concerns for business (Economist Intelligence Unit, EIU, 2003) regarding legal security for agreements, but also for less apparent causes related to NCAs and the way national courts will act to the new changes. Because with the replacement, the Council also declared the whole of Art. 101 and 102 directly applicable, meaning that NCAs and national courts are obliged to enforce EU Competition Law alongside their national legislation which essentially decentralizes the executive powers of the DG Competition. (Wigger & Nölke 2007, p. 496f) This officially gave the NCAs the power to enforce rules, act on their own initiative in EC cases and decide on anti-competitive practices. The concern for business was expressed as a concern for “forum shopping”, where firms would undertake deals in “lenient” countries, essentially undermining the “one-stop-shop”. (Ruttley 2003) But how can such a decentralization of supranational power occur, when the neofunctionalist paradigm only predicts movements towards further integration? To understand this apparent conflicting phenomenon, it is necessary to analyse the reasons for the introduction of Regulation 1/2003 and the underlying agenda of the Commission. I will hereby show, that the actual facts of the case do not disprove neofunctionalism, but at the same time points in the direction of an entirely different phenomenon related to EU governance 4 In the 1990s the DG competition focused on primarily liberalisation of key industries, internationalisation of EU competition policy as well as intensified the fight against cartels. (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10) The next major policy change after 1989 happened in 2003 6 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy which goes further that the neofunctionalist/intergovernmentalist debate and effectively illustrates the need for additional theoretical tools when understanding EU policy making. The two-tier aspect of Regulation 1/2003 was the result of several related problems which the Commission struggled with especially in the 1990s, but also since the adoption of Regulation 17/62. (Buch-Hansen, lecture 10) Firstly, the Prenotification system caused a considerable case overload of “routine notifications” for all sorts of agreements, and block exemptions were widely used for a range of agreements (e.g. agreements on common premiums in the insurance sector) which constituted a functional problem. (Ruttley 2003) But by shifting the burden of proof to companies undertaking agreements, by abolishing the prenotificiation system, the DG Competition freed up capacity to investigate and pursue cartels and highprofile cases. (Ruttley 2003) Secondly, the DG faced a problem of being repeatedly accused of exercising uncontrollable Commission power and of being a directorate with little to no credibility or legitimacy. By making Art. 101 and 102 directly applicable, an apparent decentralization of power to the NCAs and national courts should satisfy critics of the directorate as well as appearing as if decisions were taken closer to the actors concerned. (Wigger and Nölke 2007, p. 502f) This is reflected by the fact, that the Council accepted the proposed Regulation 1/2003 without any major modifications. (Wigger and Nölke 2007, p. 506) However, it can very much be argued that the Commission did not give up any executive power at all, since the NCAs and national courts were made subject to a far-reaching control by the Commission, as determined by Art. 16 of the regulation. The Commission was given the right to intervene and withdraw cases from national authorities, in cases where “decisions running counter to the decision adopted by the Commission” (Wigger and Nölke 2007, p. 502, line 31-32) should occur, essentially imposing forced convergence of national- and EU competition law, because no variations were allowed when Arts. 101 and 102 were made directly applicable. To add to this point, concern was raised as to whether national judges possessed the competences necessary for economic and legal analysis at this level, (Ruttley 2003) resulting in either the withdrawal of a case if it appears the “wrong” decisions is about to be made, or that a Guidance Letter be issued from the DG Competition, which was expected to be a strong persuasive authority. (EIU 2003) The adoption of Regulation 1/2003 can thus be said to be a curious mix of apparent decentralization and a new burden of proof placed on companies undertaking agreements. However, the obvious victor of this policy change must be said to be the Commission who achieved a remarkably increase of capacity in the competition area, as well as established incremental convergence of national competition law towards the EU model. Also, the Commission acted against the wishes of businesses and corporate lobby groups when abolishing the prenotification system, something not very likely in the neofunctionalist framework. Such an 7 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy independent and resilient position of a supranational institution was never part of the neofunctionalist logic and in order to understand and explain it, we need to move beyond the dichotomy of supranationalism and intergovernmentalism which has dominated the EU Integration debate with their constrasting approaches. Because the dichotomy offers little to no help when it comes to the actual political functioning in major policy areas, and several theories concerned with EU governance, as opposed to theories only concerned with integration, can instead enlighten and explain this development. By approaching Regulation 1/2003, whilst still accepting the basic supranational premises of neofunctionalism because it has been shown that the integration process indeed goes beyond the wishes of member states, in a new framework concerned with the EU as an existing polity, it is possible to obtain an accurate understanding of the policy mechanisms. With the obvious strengthening of the Commission it is interesting to apply New Institutionalism (NI), which stipulates that institutions are not neutral actors in a political process, but have the potential of becoming autonomous political actors in their own rights. (Bache et al. 2011, p. 22f) NI emerged as a reaction to the strongly behavioural focus in the 1960s and 70s, and stressed that neither was the overly formal institutional analysis previously used, nor the entirely sociologically/behaviourally tendency of the 60s and 70s, accurate. They both overlooked key aspects of the EU policy process, respectively the informal patterns of institutions, as well as the fact that institutions actually do shape group behaviour and establish rules and recognized points of access to the political process. Several subtypes of institutionalism emerged with a variety of applications, but they overlap rather than contrast each other. Especially Rational Choice Institutionalism (RCI) has contributed to understanding how supranational institutions can evolve and become autonomous political actors by approaching national governments as principals, and supranational institutions as agents in a principal-agent framework. (Bache et al. 2011, p. 22ff) The process starts when agency relationships are created and principals delegate responsibility for functions to agents, normally in order to lower transaction costs. However, agents may in many cases acquire more information in the field and an asymmetric distribution of information arises in favour of the agent. (Kassim & Menon 2003, p. 122) The agent can then, and often does, engage in opportunistic behaviour which can be directly against the wishes of the principal, but can be very difficult to detect. And while the agents cannot be effective if monitored and controlled too closely, an agency loss can cause delegations (or institutions) to obtain a high degree of political autonomy. (Kassim & Menon 2003, p. 125f) This model has been used to analyse relationships in the EU, and a common conception is that the “autonomy of a given supranational institution depends crucially on the efficiency and credibility of control mechanisms established by members state principals, and these vary from institution to institution”. (Kassim & Menon 2003, p. 125f, line 41-42, 1-2) 8 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy In the case of EU competition policy, it can be observed how the Commission(the agent) through the DG competition and a partnership with the EJC has expanded their capacity and worked for further European integration in e.g. the Phillip Morris case (Buch-Hansen 2012, lecture 10), acquired authority over the MCR in 1989 against the wishes of member states and NCAs, and finally with Regulation 1/2003, established themselves as a strong, autonomous actor in the EU system, out of the control of member states (the principals). Applying RCI, one can even speculate as to whether the principal-agent relationship has developed in such a way as to be reversed, so that former agents can become principals, as suggested by the fact that with Regulation 1/2003, the Commission instead of the Member States was the institution to formally delegate authority. If the agent continually increases its power at the expense of the principals, can the roles then be reversed and the process started over? Interestingly, the recent case of Tele2 Polska, where the ECJ in May 2012 ruled that the NCAs cannot state that there has been no breach of EU competition law, and companies under investigation can thus never obtain legal clearance from NCAs, has proved the dominance of the Commission in the new “decentralized” system. As consequences of the ruling, the NCAs will not be able to issue binding decisions about breaches of Art. 101 and 102, and also, the NCAs are barred from issuing individual exemptions under Art. 101 (3). (MacGregor 2012) This ruling has created major uncertainty, as all NCAs decision in the period 2004-2012 can be called into question. The development since 2003 tends to confirm what the analysis predicts – that the Commission is enhancing its power. The case of EU competition policy and the major policy changes thus cannot be explained effectively and comprehensively by neofunctionalism, nor by New Institutionalism and RCI alone, but perspectives and theories must be combined in order to describe and understand the process of European Integration, predict its developments and identify new areas of interest for scholars. Conclusion The aim of this paper has been to show how the case of EU competition policy can be used to illustrate why the interaction between a theory of EU integration and EU governance can be necessary, as well as determine the consequences for business. While neofunctionalism as a theory of European integration can be applied until a certain point, a deeper understanding of policy changes is achieved when using theories in addition to each other, instead of to falsify each other. One can ask: If theories only arise with the mission of disproving each other, do they actually portrait the world as it is anymore? In the case of competition policy, neofunctionalism effectively describes the development of the policy area through functional and political spillover in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s. In 1989 the Commission expanded their 9 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy powers as a result of a political spillover from the single market, and a functional spillover from the problems created by the Phillip Morris case, and the spillovers increased the already great legal security for European companies. However, with Regulation 1/2003, the opportunities for business rapidly deteriorated, as the burden of proof was shifted to the companies themselves. The lacks of legal security and experience of national judges created an insecure business environment where firms probably will have to allocate greater expenses to legal services, and with the Tele2Polska case, the authority of NCAs and previous decisions made, have been called into question. However, in time the effects may not all be negative if corporate lobby groups manage to address both the Commission and the NCAs appropriately and make use of the new access points to the policy making process. The one indisputable observation that can be made is that the Commission has expanded its capacity greatly, and as it was stated: “Were Member States given the choice today, they would probably not delegate the same powers to the Commission as they did 40 years ago”. (Smith 1998 in Bache et al. 2011, p. 359) Bibliography Title Author Origin Bache, Ian, George, Stephen & Oxford University Press, 3rd Edition Bulmer, Simon (Bache et. Al 2011) 2011 Rethinking the history of European Buch-Hansen, Hubert (Buch-Hansen Department of Intercultural level merger control: 2009) Communication and Management, Articles & others Politics in the European Union A critical political economy CBS 2009 perspective EU regulations: Proposed Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU competition rules cause concern for 2003) EIU Viewswire, 21st Oct. 2003 business The principal–agent approach and Kassim, Hussien & Menon, Anand Journal of European Public Policy the study of the European Union: (Kassim & Menon 2003) 10:1, February 2003: pp. 121–139 Promise unfulfilled? 10 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012 Copenhagen Business School Perspectives on EU Competition Policy EU Antitrust Proceedings And MacGregor, Anne (MacGregor 2012) National Competition Authorities: A Mondaq Business Briefing, 31 May 2012 Leap In The Wrong Direction Ruttley, Phillip (Ruttley 2003) Lloyd’s List, 15th Jan. 2003 Enhanced Roles of Private Actors in Wigger, Angela & Nölke, Andreas Journal of Common Market Studies, EU Business Regulation and the (Wigger & Nölke 2007) Vol. 45, No. 2, 2007, pp. 487-513 Wilks, Stephen (Wilks 2009) International Journal of the Brussels - A sea change in competition law Erosion of Rhenish Capitalism: the Case of Antitrust Enforcement The Impact of the Recession on Competition Policy: Amending the Economics of Business, Vol. 16, No. Economic Constitution? 3, November 2009, pp. 269–288 Lectures EU Competition Policy Buch-Hansen, Hubert (Buch-Hansen Lecture 10 on the 21st May 2012 2012, lecture 10) Regional Integration and the EU Gravier, Magali (Gravier 2012, Lecture 1 on the 11th April 2012 lecture 1) 11 Amalie Korning Wedege || International Business and Politics || Summer 2012