Grower Talks Joining Forces - TGS | Total Growth Solutions

advertisement

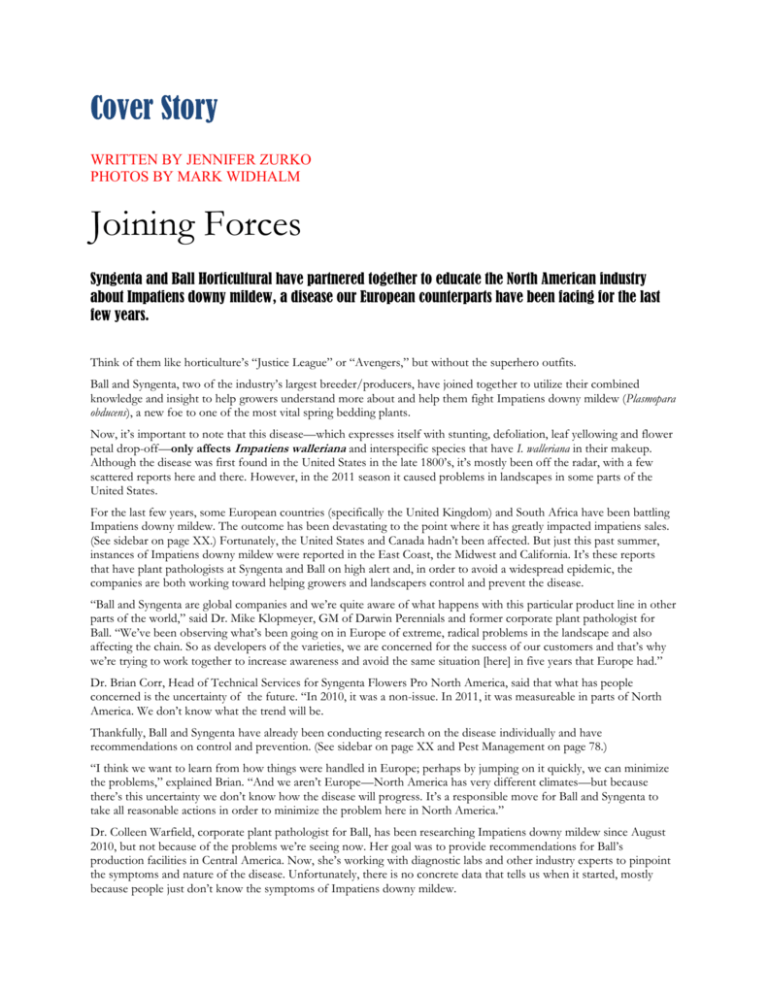

Cover Story WRITTEN BY JENNIFER ZURKO PHOTOS BY MARK WIDHALM Joining Forces Syngenta and Ball Horticultural have partnered together to educate the North American industry about Impatiens downy mildew, a disease our European counterparts have been facing for the last few years. Think of them like horticulture’s “Justice League” or “Avengers,” but without the superhero outfits. Ball and Syngenta, two of the industry’s largest breeder/producers, have joined together to utilize their combined knowledge and insight to help growers understand more about and help them fight Impatiens downy mildew (Plasmopara obducens), a new foe to one of the most vital spring bedding plants. Now, it’s important to note that this disease—which expresses itself with stunting, defoliation, leaf yellowing and flower petal drop-off—only affects Impatiens walleriana and interspecific species that have I. walleriana in their makeup. Although the disease was first found in the United States in the late 1800’s, it’s mostly been off the radar, with a few scattered reports here and there. However, in the 2011 season it caused problems in landscapes in some parts of the United States. For the last few years, some European countries (specifically the United Kingdom) and South Africa have been battling Impatiens downy mildew. The outcome has been devastating to the point where it has greatly impacted impatiens sales. (See sidebar on page XX.) Fortunately, the United States and Canada hadn’t been affected. But just this past summer, instances of Impatiens downy mildew were reported in the East Coast, the Midwest and California. It’s these reports that have plant pathologists at Syngenta and Ball on high alert and, in order to avoid a widespread epidemic, the companies are both working toward helping growers and landscapers control and prevent the disease. “Ball and Syngenta are global companies and we’re quite aware of what happens with this particular product line in other parts of the world,” said Dr. Mike Klopmeyer, GM of Darwin Perennials and former corporate plant pathologist for Ball. “We’ve been observing what’s been going on in Europe of extreme, radical problems in the landscape and also affecting the chain. So as developers of the varieties, we are concerned for the success of our customers and that’s why we’re trying to work together to increase awareness and avoid the same situation [here] in five years that Europe had.” Dr. Brian Corr, Head of Technical Services for Syngenta Flowers Pro North America, said that what has people concerned is the uncertainty of the future. “In 2010, it was a non-issue. In 2011, it was measureable in parts of North America. We don’t know what the trend will be. Thankfully, Ball and Syngenta have already been conducting research on the disease individually and have recommendations on control and prevention. (See sidebar on page XX and Pest Management on page 78.) “I think we want to learn from how things were handled in Europe; perhaps by jumping on it quickly, we can minimize the problems,” explained Brian. “And we aren’t Europe—North America has very different climates—but because there’s this uncertainty we don’t know how the disease will progress. It’s a responsible move for Ball and Syngenta to take all reasonable actions in order to minimize the problem here in North America.” Dr. Colleen Warfield, corporate plant pathologist for Ball, has been researching Impatiens downy mildew since August 2010, but not because of the problems we’re seeing now. Her goal was to provide recommendations for Ball’s production facilities in Central America. Now, she’s working with diagnostic labs and other industry experts to pinpoint the symptoms and nature of the disease. Unfortunately, there is no concrete data that tells us when it started, mostly because people just don’t know the symptoms of Impatiens downy mildew. “There are two reports that I know of in terms of diagnostic labs in the U.S. There was a report on the East Coast of a case this spring in a greenhouse facility, and then there also was a Michigan State [University] sample that went to their clinic. That was also a greenhouse sample,” said Colleen. “That was back apparently early in the spring [2011], so there was really no landscape reports until Cape Cod in August. Then as other [reports] came in, I started to send out feelers. In California, that landscape was really hammered. They didn’t know; it just happened that one of our Ball people went there on the lookout for it. But that’s triggered all sorts of people who have seen the symptoms and didn’t know what it was. So there’s no telling when it started.” Brian said Syngenta has also been conducting research on Impatiens downy mildew since the disease appeared in Europe. “[The research] has been focused on control—like Colleen, we all have the same concerns. We want to make sure that the production facilities do all they can to control the disease. So supply chain is extremely important for all of us. But we’ve also been focused on control for the grower and for the landscape because if we don’t do that, the rest of it doesn’t matter.” Quarantine questions As all seasoned growers know, this isn’t the industry’s first run-in with a challenging plant disease. Shivers run down the spine of many who experienced run-ins with Ralstonia on geraniums and Chrysanthemum white rust. But, Impatiens downy mildew is not like those diseases for many reasons—the primary one being that it doesn’t have to be quarantined by the USDA. “First, this is not an actionable quarantine pest,” Mike stated emphatically. “Chrysanthemum white rust and Ralstonia are quarantine pests, which means they’re not supposed to be found here in the U.S., and if they are, all measures are to be taken to eradicate them. But this particular one is not a regulated pest. It is a ‘quality pest’—meaning it could impact the quality of the finished plants at the grower level or it could impact at the consumer level, which could be in a landscape setting or in somebody’s back yard. It’s totally different from the other two.” Also, the research done by Ball and Syngenta suggests that the disease is not transmitted by seed, however, seed-raised impatiens are susceptible to the disease if they are exposed to the disease from infected plants. But Mike said they don’t believe this is the primary source of infection. This doesn’t mean that rooting stations and growers who buy in cuttings should switch to seed impatiens. Both Ball and Syngenta have put processes in place at their respective production locations to ensure all of the cuttings shipped out are as clean as possible. Again, most of the reports of Impatiens downy mildew have come from the landscape segment, which could categorize this as a soil-borne disease that overwinters. But Colleen said that more tests need to be conducted to confirm this since most soil-borne diseases affect the roots and that has not been the case thus far. The hort disease triangle During the discussion, Brian talked about what every student learns in horticulture school. “It’s classic Plant Pathology 101.” Making a triangle shape with his fingers, Brian refers to the first two points and says, “You have to have the susceptible plant, and the disease has to be present—but those two alone don’t make for the disease. You have to have an environment that’s favorable for the disease to develop.” And that environment is cool temperatures and moist conditions—both of which are common occurrences in the UK and Western Europe. Most of the cases in the U.S. were reported after a period of low temperatures and lots of precipitation, like what happened with the East Coast late in the summer of 2011 after Hurricane Irene. “This year, it came in late when we saw it in the landscape, which is why some people didn’t notice it,” said Mike. “It’s not like impatiens are declining. In Europe in some cases, it hit them early and it hit them hard and wiped them out in the landscape. All through the summer, they get cool, cloudy, wet weather with wind; have a high-density population; a lot of plants in the landscape; very easy movement of these spores over miles—it doesn’t take long to have a big-time problem.” Logic would suggest that since this disease only affects one species of impatiens, it would be easier to pinpoint it and eradicate it. But it’s not that simple. “The trouble is it’s one of the most important bedding plants out there that is used ubiquitously,” Mike says. “Also, the purpose of this is to increase awareness for people to look for symptoms and, if you have to down the line, do crop 2 rotations at the landscape level within those particular beds if they saw symptoms the previous season. Try to lessen the impact of the disease by avoiding putting the host in there and rotate them, which you should be doing anyway.” Brian admits that he’s guilty of planting impatiens in the same bed in his backyard for the last eight years … and he saw the start of Impatiens downy mildew toward the end of the season. “It was probably there all summer, but there were no obvious symptoms,” said Brian. “The plants were a little funky, which we often see with these things, but as soon as it got cold and wet, you got sporulation. And honestly, they really didn’t die until we were getting frosty nights. And then it was like, well, did the frost take them or did the disease take them? It was kind of a race. My wife never noticed anything was wrong with the plants since they were already going down because of the cold.” Avoiding Henny Penny Although nothing beats the color range offered by impatiens, there are other options, especially since the disease doesn’t affect other plants. Begonias and coleus are obvious choices to replace impatiens because of their shade tolerance. New Guinea impatiens are another choice because of their tolerance to the disease. Growers in the UK are also trying out phlox and cosmos. Growers in North America should be aware of their market and have a Plan B ready if their spring impatiens crop starts to show signs of the disease. But both Syngenta and Ball were steadfast in their message that growers should continue to offer this core crop for this coming spring. Their efforts to educate all levels of the supply chain have made them hopeful that the likelihood of a widespread outbreak is minimal. “Right now, we think it’s very early on and we’re increasing awareness so it can be managed,” explained Mike. “[The growers] need to be looking and scouting the disease at the greenhouse level, and if they’re hearing reports back from the landscape of problems in that bed, get it properly diagnosed to make sure that’s what it is and then work closely with their landscapers to look at alternate crops to rotate.” Colleen agreed. “The confirmed cases are regional, so the reality is the number of landscapers that are going to actually be impacted is really kind of miniscule. So probably far fewer people will ever be impacted as long as they follow the recommendations and it doesn’t get out of hand.” Both of these companies want to get the word out quickly so that growers were armed with enough knowledge to be on the look out during the next vital growing months. Brian said it was important for Syngenta and Ball to sit down at the same table and figure out a way to inform the industry about Impatiens downy mildew without it becoming another “Chicken Little” story. “We don’t know if the problem will just go away or if this is going to become something more significant,” said Brian. “That’s why we’re here. Let’s minimize the spread of the disease so we can minimize potential problems in the future. Let’s do the prudent things now even if we don’t really know what we need to do. Even if it just goes away on its own, we’ve done what we can do to be responsible stakeholders in this industry.” GT 3