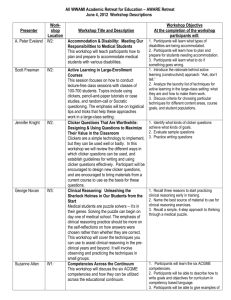

Unconscious bias in higher education

advertisement