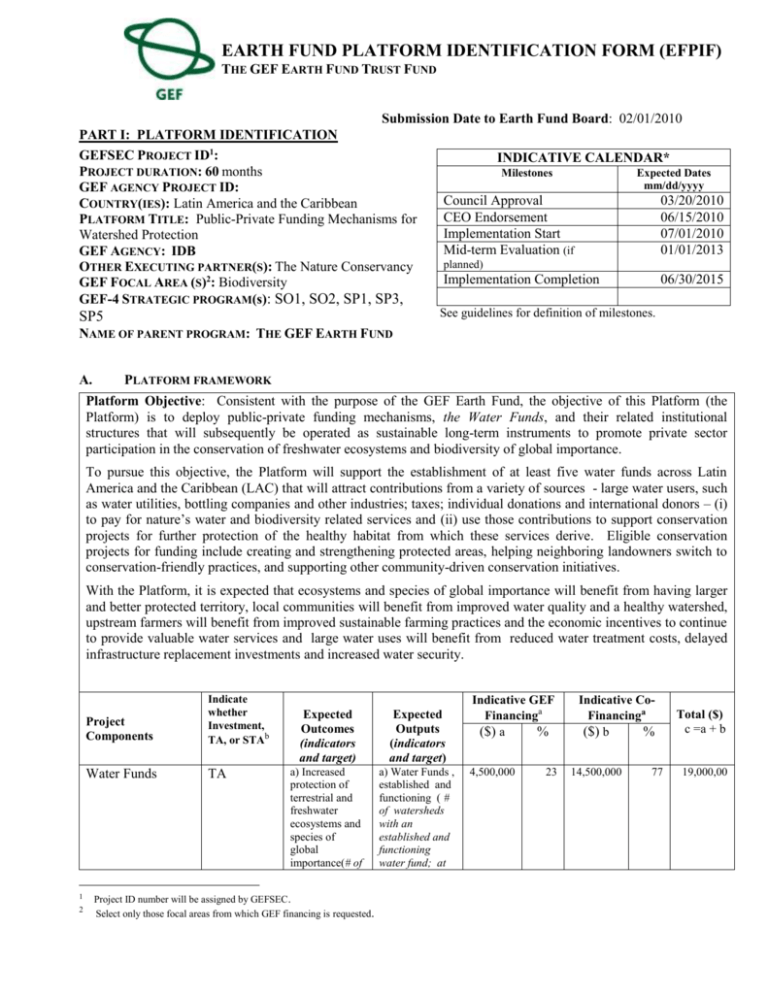

FINANCING PLAN (IN US$): - Global Environment Facility

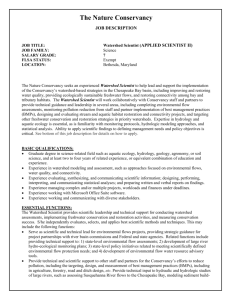

advertisement