SYMBOL/SYMBOLISM Source 1: Murfin, Ross and Supryia M. Ray

advertisement

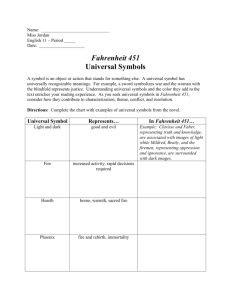

SYMBOL/SYMBOLISM Source 1: Murfin, Ross and Supryia M. Ray. The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary Terms. 2nd ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2003. 470-473. Print. symbol: Something that, although it is of interest in its own right, stands for or suggests something larger and more complex - often an idea or a range of interrelated ideas, attitudes, and practices. Within a given culture, some things are understood to be symbols: the flag of the United States is an obvious example, as are the five intertwined Olympic rings. More subtle cultural symbols might be the river as a symbol of time and the journey as a symbol of life and its manifold experiences. Instead of appropriating symbols generally used and understood within their culture, writers often create their own symbols by setting up a complex but identifiable web of associations in their works. As a result, -one object, image, person, place, or action suggests others, and may ultimately suggest a range of ideas. A symbol may thus be defined as a metaphor in which the vehicle the image, activity, or concept used to represent something else represents many related things (or tenors) or is broadly suggestive. The urn in John Keats's "Ode on a Grecian Urn" (1820) suggests interrelated concepts, including art, truth, beauty, and timelessness. Certain poets and groups of poets have especially exploited the possibilities inherent in symbolism; these include the French Symbolist poets of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, such as Charles Baudelaire, Stephane Mallarrne, Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Valery, and Paul Verlaine. Symbols are distinguished from both allegories and signs. Like symbols, allegories present an abstract idea through more concrete means, but a symbol is an element of a work used to suggest something else (often of a higher or more abstract order), whereas an allegory is typically a narrative with two levels of meaning that is used to make a general statement or point about the real world. Symbols are typically distinguished from signs insofar as the latter are arbitrary constructions that, by virtue of cultural agreement, have one or more particular significations. Symbols are much more broadly suggestive than signs. As a sign, the word water has specific denotative meanings in the English language, but as a symbol, it may suggest concepts as varied or even divergent as peace or turmoil, the giver of life or the taker of it. Some theorists (such as Charles Sanders Peirce), however, have argued that symbols are in fact a type of sign, their meanings just as arbitrary and culturally determined as those of signs. Symbols have been of particular interest to formalists, who study how meanings emerge from the complex, patterned relationships among images in a work, and psychoanalytic critics, who are interested in how individual authors and the larger culture both disguise and reveal unconscious fears and desires through symbols. Recently, French feminist critics have also focused on the symbolic. They have suggested that, as wide-ranging as it seems, symbolic language is ultimately rigid and restrictive. They favor semiotic language and writing - writing that neither opposes nor hierarchically ranks qualities or elements of reality nor symbolizes one thing but not another in terms of a third - contending that semiotic language is at once more fluid, rhythmic, unifying, and feminine. EXAMPLES: In the following passage from The Old Man and the Sea (1952), Ernest Hemingway uses traditional literary and biblical symbols to speak suggestively about human mortality, faith that flies in the face of suffering and death, and the ultimate spiritual triumph over limitation and loss. These symbols include the quiet harbor, the sheltering rock, the struggle with a cross-like mast, and the great, slippery, luminous fish: When he sailed into the little harbour the lights of the Terrace were out and he knew everyone was in bed. The breeze had risen steadily and was blowing strongly now. It was quiet in the harbour though and he sailed up onto the little patch of shingle below the rocks. There was no one to help him so he pulled the boat up as far as he could. Then he stepped out and made her fast to a rock. He unstepped the mast and furled the sail and tied it. Then he 'shouldered the mast and started to climb. It was then he knew the depth of his tiredness. He stopped for a moment and looked back and saw in the reflection from the street light the great tail of the fish standing up well behind the skiff's stern. William Golding's Lord of the Flies (1954) also contains numerous symbolic passages, such as the scene depicting Simon's death, inflicted by a mob-like group of young boys. The young but wise Simon is a Christ figure who dies unjustly; he is killed, in fact, by his peers (reminiscent of the judgment of Christ's peers condemning him to death) while trying desperately to help them by bringing knowledge that will change their lives. Even nature protests Simon's death with the opening of the clouds, torrential rain, and a great wind, just as God opened the heavens, darkened the sky, and let the rain pour down at the moment of Christ's death: The sticks fell and the mouth of the new circle crunched and screamed. The beast was on its knees in the center, its arms folded over its face. It was crying out against the abominable noise something about a body on the hill. The beast struggled forward, broke the ring and fell over the steep edge of the rock to the sand by the water. At once the crowd surged after it, poured down the rock, leapt on to the beast, screamed, struck, bit, tore. There were no words, and no movements but the tearing of teeth and claws. Then the clouds opened and let down the rain like a waterfall. The water bounded from the mountain-top, tore leaves and branches from the trees, poured like a cold shower over the struggling heap on the sand. Presently the heap broke up and figures staggered away. Only the beast lay still, a few yards from the sea. Even in the rain they could see how small a beast it was; and already its blood was staining the sand. Now a great wind blew the rain sideways, cascading the water from the forest trees … In the February 2001 episodes of the "reality-TV" series Survivor II: The Australian Outback, the recurring image of a spider served not only as a symbol of the predatory nature of certain characters but also of the "game" of survival more generally. symbolism: From the Greek symballein, meaning "to throw together," the serious and relatively sustained use of symbols to represent or suggest other things or ideas. In addition to referring to an author's explicit use of a particular symbol in a literary work ("Joseph Conrad uses snake symbolism in Heart of Darkness" [1899]), the term symbolism sometimes refers to the presence, in a work or body of works, of suggestive associations giving rise to incremental, implied meaning ("I enjoyed the symbolism in George Lucas's Star Wars movies" [1977- ]). When spelled with a capital S, Symbolism refers to a literary movement that flourished in late-nineteenth-century France and whose adherents rebelled against literary realism. Symbolists (often referred to specifically by nationality as the French Symbolists) held that writers create and use subjective, or private (rather than conventional, or public), symbols in order to convey very personal and intense emotional experiences and reactions. They argued that networks of such symbols form the real essence of a literary work. Because of the subjective and individual character of their symbolic systems, the work of the French Symbolists is more suggestive than explicit in meaning. Charles Baudelaire, Stephane Mallarrne, Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Valery, and Paul Verlaine are probably the best known of the French Symbolists. Many other writers could also be called symbolists because of the sustained use in their works of "private" symbol systems - even though they preceded, succeeded, or simply did not participate in the better known (and more organized) French movement. Such writers include William Blake, Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, D. H. Lawrence, and William Butler Yeats. Poe's poetic practice and theory in particular had a considerable influence on the French Symbolists. Thus, although literary historians tend to limit the use of Symbolism to refer to a specific literary movement that developed in France, the movement in fact had its roots - and perhaps has had its greatest impact and influence - beyond French borders. Twentieth-century European and American writing owes a particular debt to Symbolism. Authors ranging from the German Rainer Maria Rilke to the English Arthur Symons to the Irish Yeats and James Joyce to Americans like Wallace Stevens and T. S. Eliot have drawn on but also extended the work of the French Symbolists. Source 2: Harmon, William and C. Hugh Holman. A Handbook to Literature. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1996. 507-509. Print. Symbol A symbol is something that is itself and also stands for something else; as the letters a p p l e form a word that stands for a particular objective reality; or as a flag is a piece of colored cloth that stands for a country. All language is symbolic in this sense, and many of the objects that we use in daily life are also. In a literary sense a symbol combines a literal and sensuous quality with an abstract or suggestive aspect. It is advisable to distinguish symbol from IMAGE, ALLEGORY, and METAPHOR. If we consider an image to have a concrete referent in the objective world and to function as image when it powerfully evokes that referent, then a symbol is like an image in doing the same thing but different from it in going beyond the evoking of the objective referent by making that referent suggest a meaning beyond itself; in other words, a symbol is an image that evokes an objective, concrete reality and prompts that reality to suggest another level of meaning. The symbol evokes an object that suggests the meaning. As Coleridge said, "It partakes of the reality which it renders intelligible." In allegory the objective referent evoked is without value until it is translated into the fixed meaning that it has in its own particular structure of ideas, whereas a symbol includes permanent objective value, independent of the meanings that it may suggest. In "The Rhetoric of Temporality," Paul de Man argues that "Whereas the symbol postulates the possibility of an identity or identification, allegory designates primarily a distance in relation to its own origin, and, renouncing the nostalgia and the desire to coincide, it establishes its language in the void of this temporal difference." A metaphor evokes an object in order to illustrate an idea or demonstrate a quality, whereas a symbol embodies the idea or the quality. As W. M. Urban said, "The metaphor becomes a symbol when by means of it we embody an ideal content not otherwise expressible." Literary symbols are of two broad types: One includes those embodying universal suggestions of meaning, as flowing water suggests time and eternity, a voyage suggests life. Such symbols are used widely (and sometimes unconsciously) in literature. The other type of symbol acquires its suggestiveness not from qualities inherent in itself but from the way in which it is used in a given work. Thus, in Moby-Dick the voyage, the land, the ocean are objects pregnant with meanings that seem almost independent of Melville's use of them in his story; on the other hand, the white whale is invested with meaning-and differing meanings for different crew members-through the handling of materials in the novel. The very title of The Scarlet Letter points to a double symbol: a color-coded letter of the alphabet; the work eventually develops into a testing and critique of symbols, and the meanings of "A" multiply. Thomas Pynchon's V. continues much the same line of testing an alphabetical symbol. Similarly, in Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms, rain, which is a mildly annoying meteorological phenomenon in the opening chapter, is converted into a symbol of death through the uses to which it is put in the book. The meaning of practically any general symbol is thus partly a function of its environment. Symbolism In its broad sense symbolism is the use of one object to represent or suggest another; or, in literature, the serious and extensive use of SYMBOLS. Recently the word has taken on a pejorative connotation of mere rhetoric without reality, surface without substance, speciousness and tokenism, all smoke and no fire, all hat and no cattle. In America in the middle of the nineteenth century, symbolism of the sort typical of romanticism was the dominant literary mode. In this movement the details of the natural world and the actions of people were used to suggest ideas. Romantic symbolism was the fundamental practice of the transcendentalists. Emerson, the chief exponent of the movement, declared that "Particular natural facts are symbols of particular spiritual facts" and that "Nature is the symbol of spirit," and Henry David Thoreau made life itself a symbolic action in Walden. The symbolic method was present in the POETRY of these two and also in that of Walt Whitman. Symbolism was a distinctive feature of the novels of Hawthorne-notably The Scarlet Letter and The Marble Faun--and of Melville, whose Moby-Dick is probably the most original work of symbolic art in American literature. Symbolism is also the name of a movement that originated in France in the last half of the nineteenth century, strongly influenced British writing around the turn of the century, and has been a dominant force in much British and American literature in the twentieth century. This symbolism sees the immediate, unique, and personal emotional response as the proper subject of art, and its full expression as the ultimate aim of art. Because the emotions experienced by a poet in a given moment are unique to that person and that moment and are finally both fleeting and incommunicable, the poet is reduced to the use of a complex and highly private kind of symbolization in an effort to give expression to an evanescent and ineffable feeling. The result is a kind of writing consisting of what Edmund Wilson has called "a medley of metaphor" in which symbols lacking apparent logical relation are put together in a pattern, one of whose characteristics is an indefiniteness as great as the indefiniteness of experience itself and another of whose characteristics is the conscious effort to use words for their evocative musical effect, without much attention to precise meaning. As Baudelaire, one of the principal forerunners of the movement, said, human beings live in a "forest of symbols," which results from the fact that the materiality and individuality of the physical world dissolve into the "dark and confused unity" of the unseen world. In this process SYNAESTHESIA takes place. Baudelaire and the later symbolists, particularly Mallarme and Valery, were deeply influenced by Poe's theory and poetic practice. Other important French writers in the movement were Rimbaud, Verlaine, Laforgue, Gourmont, and Claudel, as well as Maeterlinck in the drama and Huysmans in the novel. The Irish writers of this century, particularly Yeats in poetry, Synge in the drama, and Joyce in the novel, have been notably responsive to the movement. In Germany, Rilke and Stefan George were great symbolist poets. In America, the imagist poets reflected the movement, as did Eugene O'Neill in the drama. Through its pervasive influence on T. S. Eliot, symbolism has affected much of the best British and American poetry in our time. One of the most evocative passages of symbolist poetry is that beginning "Garlic and sapphires in the mud" in Eliot's "Burnt Norton."