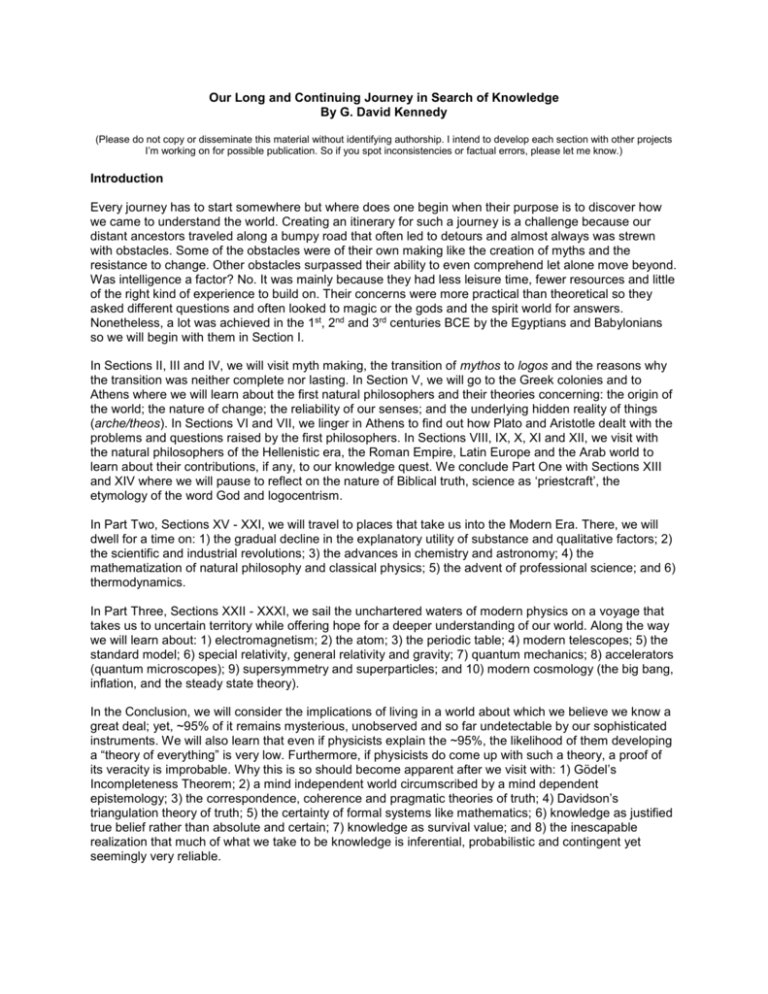

Intro & Part One of Our Long and Continuing Journey in

advertisement