develop ment co-ord - symp1

advertisement

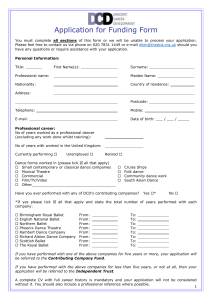

Determining appropriate supports for students with Developmental Co-ordination Disorder in third level education Trish Ferguson Disability Service University of Dublin Trinity College June 2010 Seirbhís do dhaoine faoí mhíchumas, Seomra 2054, Foígneamh na nEalaíon Coláiste na Tríonóide, Baile Átha Cliath 2, Éire Disability Service, Room 2054, Arts Building, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland 1 Contents Abstract Section 1: Literature review 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Symptoms of Developmental Coordination Disorder 1.3 Assessment 1.4 Prevalence 1.5 Co-morbidity Section 2: DCD at third level 2.1 Applications through Disability Access Route to Education (DARE) 2.2 Students with DCD at Trinity College Dublin 2.3 Statistics 2.4 CAO: personal statements 2.5 TCD: course choice 2.6 TCD: retention Section 3: Determining appropriate supports for third level 3.1 Specific educational impacts 3.2 Motor difficulties 3.3 Non-motor difficulties 3.4 Reasonable accommodations 3.5 Suggested teaching supports Lectures Seminars Written work 3.6 Assistive Technology (AT) 3.7 Academic Support 3.8 Unilink (OT-based one-to-one support) Section 4: Summary 4.1 Discussion 4.2 Further research References and Bibliography 2 Abstract This presentation is a discussion of the difficulties encountered in adulthood associated with DCD and specifically the difficulties experienced in the student population at third level. Although the population is not homogenous DCD may present as any number of the following difficulties: abnormalities in postural control and/or fine motor skills; difficulties in learning motor tasks, such as handwriting and sports; difficulties with educational tasks, such as reading comprehension, attention and learning; poor time management. This paper discusses aetiology, assessment and will examine trends in course choices and retention rates within this group in recent years in Trinity College. This study will then consider requirements within learning support and reasonable accommodations for examinations. It will also consider appropriate interventions for students in practical courses, considering the requirements and possible interventions in laboratory work and placement situations. It also makes recommendation on provision of supports at third level and suggests further research and data collection will assist with future developments. 3 Section 1: Literature review 1.1 Introduction Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD), also known as dyspraxia, is the term now internationally recognised to describe ‘a specific learning difficulty in gross and fine motor planning which is not caused by muscle/nerve damage’ (Poustie et al., 1997). Developmental Coordination Disorder is preferred over the term ‘dyspraxia’. (Gibbs et al., 2007) The educational impact of DCD on children is well documented but there are few studies on teenagers (Kirby 2004, Hellgren et al., 1994a; Losse et al., 1991) or adults with DCD (Barnett and Kirby, 2009; Kirby et al., 2008a; Kirby et al., 2008b; Colley, 2006; Cousins & Smyth, 2003; Visser, 2003; Rasmussen and Gillberg, 2000; Cantell et al., 1994; Geuze and Börger, 1993). This is because most often a diagnosis is made prior to school age and in the first few years of primary school on account of obvious difficulties with achieving age-related milestones that involve motor skills, like crawling, eating, dressing and brushing teeth. Until recent years DCD has been the subject of less research-based study than dyslexia. Due to this and the variability of the disorder, which makes it more difficult to diagnose, it is expected that a significant number of people with DCD now in adulthood have not been diagnosed in childhood. Early case histories of children with DCD suggested that a proportion do improve (Dare & Gordon 1970; Gubbay, 1975) but more recent research indicates persistence and impact in adult life (Kirby et al., 2008; Cousins & Smyth, 2003). Kirby et al. (2008) finds that ‘between 30 and 87% of children with DCD will continue to exhibit poor co-ordination into adulthood’ (199). Recent studies on DCD in adulthood have focused on psycho-social outcomes (Rasmussen and Gillberg, 2000) and specific motor skills, such as handwriting and construction tested under timed conditions (Cousins & Smyth, 2003). A forum was launched in 2006 for adults with DCD (http://www.dyspraxicadults.org.uk) and there has been a growing body of research conducted on adults with DCD particularly in the last ten years, 4 however, the experience of adults with DCD in third level education remains under-researched. As a result of successful implementation of supports at second level, more students are accessing third level education with a diagnosis of DCD and seeking supports. This study aims to document the specific educational impacts of DCD in third level education and to make recommendations for intervention. These recommendations will then be critiqued in terms of universal design and considered regarding the practicalities of implementation with consideration given to resources available, funding restrictions and fitness to practice issues. 1.2 Symptoms of Developmental Coordination Disorder Although the population is not homogenous DCD may present as any number of the following difficulties: abnormalities in postural control (Wann et al., 1998; Williams and Wollacott, 1997), as well as in fine motor skills (Smits-Engelsman et al., 2001), difficulties in learning motor tasks, such as handwriting and sports (Losse et al., 1991); educational tasks, such as reading comprehension (Kadesjo and Gillberg, 1999); attention and learning (Dewey et al., 2002; Landgren, Kjellman, & Gillberg, 1998; Kadesjo & Gillberg, 1998; Hellgren, Gillberg, & Gillberg, 1994a; Gillberg & Rasmussen, 1982; Gillberg, Rasmussen, Carlstrom, Svenson, & Waldenstrom, 1982;); time management (Kirby, 2004; Dewey et al., 2002); behavioural problems (Dewey, Kaplan, Crawford & Wilson, 2002; Losse et al., 1991); social skills and low self-esteem. (Poulsen, Ziviani & Cuskelly, 2007; Cousins & Smyth, 2003; Cantell, Smyth, & Ahonen, 1994) 1.3 Assessment DCD is assessed by the DSM-IV criteria for DCD developed by the APA or by ICD-10, developed by the World Health Organization. According to the DSM-IV the diagnostic criteria for DCD are as follows: 5 A. Performance in daily activities that require motor coordination is substantially below that expected given the person’s chronological age and measured intelligence. This may be manifested by marked delays in achieving motor milestones (e.g., walking, crawling, sitting), dropping things, “clumsiness,” poor performance in sports, or poor handwriting. B. The disturbance in Criterion A significantly interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily living. C. The disturbance is not due to a general medical condition (e.g., cerebral palsy, hemiplegia, or muscular dystrophy) and does not meet criteria for a Pervasive Developmental Disorder. D. If Mental Retardation is present, the motor difficulties are in excess of those usually associated with it. The following specialists make assessments for, and diagnose dyspraxia: psychologists – educational, occupational or neurological; paediatricians who specialise in developmental disorders, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Tests used for assessment should be age appropriate in all cases. In the UK, the most commonly used test for motor-related difficulties in children is the Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 (Movement ABC-2) (Henderson & Sugden, 2007). Movement ABC-2 is appropriate for assessing children up to 12 years. The Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency-2 (2005) is a standardized, norm-referenced measure of fine and gross motor skills that has norms up to the age of 21 years. There are two versions of this test: the full version which takes 2 hours and a shorter form which takes 30 min to administer (Bruininks, 1978). There is not as yet an adequate test for a range of motor skills for adults older than 21 (Kirby at al., 2008b). Acknowledging that adolescents have a different range of motor skill requirements than children Kirby (2004) states: ‘In order to diagnose adolescents we need to consider what are the unique features that highlight the co-ordination difficulties. If we use the DSM-IV criteria as a guideline for this, in the adolescent, 6 as with the child, it is ‘impairment significantly interfering with academic achievement or activities of daily living’ (author’s emphasis) which is the most important to consider. We then need to highlight in this age group what they are likely to be.’ (17) The same is true of adults and this will be considered in relation to needs assessment in university for this group. The Morrisby Manual Dexterity Test is used for assessment of students entering university to assess fine motor control indicators for difficulties associated with DCD in adults is the (Morrisby, 1991). However, this tests only fine motor actions in one setting and will not identify gross motor or balance difficulties rather than fine motor difficulties (Kirby et al., 2008b). Kirby (2010) notes that ‘Current tests are able to measure motor functioning (Criterion A of the DSM-IV), but are not able to consider how and where the difficulties impact on the adult's life (Criterion B of the DSM-IV).’ A new screening tool is currently under development in order to provide appropriate interventions for adult life (Kirby, 2010). Currently recommended by Kirby (2010) is The Adult Developmental Co-ordination Disorders/Dyspraxia Checklist (ADC) which assesses ability within home, academic and social environments including ‘handwriting, driving, attention, organisation in time and space abilities and social skills’ (133). Kirby (2010) concludes: ‘this is an area for further research that has clinical implications for service providers such as universities, colleges, and occupational therapy services’ (137). While the Adult Developmental Co-ordination Disorders/Dyspraxia Checklist (ADC) is a useful tool for adult diagnosis through studying a person’s childhood history it is not a tool for determining supports in any given environment, including university. Developing an assessment for students entering university is difficult because of the different tasks required for each course, some requiring more use of motor skills than others and also on account of the heterogeneity of difficulties associated with DCD. As Politajko (1999) notes on a study of children, ‘one child with DCD is likely to be excellent at one motor task but poor at another.’ The same is true of adults. 7 As yet there is no specific standardized assessment for academic environments and tasks, including handwriting and exam accommodations, laboratory work or placements. While it is useful to have a history of a person’s motor skill abilities, the development of an assessment tool for students entering university with DCD must also take into consideration difficulties associated with other developmental disorders on account of the high level of co-morbidity. 1.4 Prevalence Studies in the United Kingdom suggest that between 5 and 18 per cent of individuals are affected by DCD (Godfrey, 1994; Hall, 1994; Marks, 1994; Portwood, 1996, cited in Dixon and Addy, 2004, 9). The American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2000) cites the prevalence at 6% for children in the age range of 5–11 years. Males are more likely to be affected than females; a study of children with DCD in Sweden, found a boy: girl ratio of 5.3:1 (Kadesjö and Gillberg 1998). It is difficult to assess prevalence in adulthood on account of there being no commonly used standardized screening tool for adult assessment. The Bruininks Oseretsky Test-2 (Bruininks & Bruininks, 2005), which is normed up to 21 years is used in the United States (Kirby 2010) but is not commonly used in the UK or Ireland. The assessment most commonly used for adults is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales (WAIS) which can reveal a pattern of weaknesses and strengths typical of DCD but is an assessment tool used primarily for specific learning difficulties and not specifically DCD. It is also difficult to assess prevalence in adulthood because of the high level of comorbidity on account of which a diagnosis is often made on another developmental disorder in adulthood rather than DCD. 1.5 Co-morbidity With all developmental disorders there is a high level of co-morbidity but this is particularly so with DCD. Having DCD with only motor difficulties is the exception 8 rather than the rule (Peters & Henderson, 2008). DCD co-occurs commonly with dyslexia and ADHD (Barnett and Kirby 2009, Visser, 2003, Dewey et al., 2002; Dewey et al., 2000; Gillberg, 1998; Gillberg and Kadesjö, 2000; Gillberg and Kadesjö, 1998; Kadesjö and Gillberg, 2001; Martini et al., 1999; Kaplan et al., 1997). Also, Kirby, Salmon and Edwards (2007, 336) note that ‘there is clear evidence of association or co-morbidity of ADHD with a number of other psychiatric conditions, including oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and depression and anxiety disorders (Loeber, 1982; Barkley et al., 1990; Taylor et al., 1991), and these should be routinely considered at the time of assessment.’ However, in their study they note that it is not known whether clinicians routinely check other developmental disorders during assessment despite the fact that statistics suggest that prevalence of co-morbidity with ADHD may be up to 50% (Kadejs & Gillberg 1999) and there is also a high co-morbidity with specific learning difficulties. Section 2: DCD at third level 2.1 Applications through Disability Access Route to Education (DARE) In recent years Dyspraxia has become assessed and recognised as a distinct disability having previously been grouped under Specific Learning Difficulty in college application processes. The application process remains the same but evidence is now required to state a diagnosis of Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) / Dyspraxia. Candidates applying for College through the Disability Access Route to Education (DARE) must submit a full psychoeducational assessment from the Psychologist and the Evidence of Disability Form which should be completed by an Occupational Therapist/Physiotherapist. The applicant is eligible for consideration once the appropriate professionals have provided a diagnosis of Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) / Dyspraxia. While there is no age limit on diagnostic evidence submitted applicants are advised to submit a recent report. Applicants who have an existing 9 report completed by the accepted Medical Consultant/Specialist may submit this report. The report must have been completed within the appropriate timeframe and must contain the same detail as the Evidence of Disability Form. The report should state difficulties from childhood or evidence from a specialist that there is historical information which evidences Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) / Dyspraxia, and that the applicant is presenting with difficulties that has impacted on home and school. For adult assessments the standardized Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) / Dyspraxia Checklist should be referenced, which is in line with the DSM IV/ICD10 (Kirby 2010). Applications through DARE must also include the student’s personal statement which should outline the impact of disability on their academic and educational experience to date. An academic reference is also required which provides background information on the student’s educational experience and can confirm challenges, stating the educational impact of disability and describing the need for any teaching and learning adjustments. This form also helps to determine appropriate supports at third level. Table 1: DARE applications: students with DCD 120 110 100 74 80 60 40 32 20 0 2008 2009 2010 2.2 Students with DCD at Trinity College Dublin 10 There are currently 20 students with DCD registered with Trinity College’s Disability Service, 15 active, 3 withdrawn and 2 graduands. 14 are male and 6 are female. This is a ratio of 7:3, compared with 5.3:1 in Kadesjö and Gillberg (1998). The slightly higher number of females may be accounted for by the gender breakdown of the College population as a whole, as there are a significantly higher number of female undergraduates than males in the College population as a whole. 2.3 Statistics Table 2: College Standing 12 10 10 8 6 5 4 3 2 2 0 Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 graduand withdrawn Table 3: Ages of students registered with DCD 11 18 17 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 1 2 0 19-21 22-24 25-26 26-30 31-35 35+ 17 of the 20 students registered are aged between 19 and 20. This accounts for 85% of this group, which are primarily first and second years so this means that students are coming directly to College from secondary school. It may be that they have been well supported in school which accounts for their successful transition in their first application. As will be shown below, a high proportion of students with DCD entered on merit rather than via the supplementary admissions process. It should be noted however, that the 3 students who have withdrawn from College are all within this 19-21 age bracket, two having withdrawn without completing first year and one other in second year. Table 4: Breakdown by Entry Route 12 14 13 12 10 8 6 6 4 2 1 0 Merit Supplementary Mature The chart above shows that 13 students (65% of this group) entered on merit, 6 students (30%) via the supplementary system and 1 student (5%) entered as a mature student. These statistics are not particularly helpful as an indication of a student’s experience of college due to the nature of the disability which can be exacerbated by a change of environment and requirements and as the majority of students are still in first year it is not yet possible to comment on progression/retention rates for this group. As noted above, immediate progression from school and also a high rate of entry on merit suggests success at school level, whether on account of the nature of the environment, which is more directive than university, or whether this is due to the success of supports put in place at second level. Taking this into consideration emphasizes the importance of the needs assessment stage at third level to ascertain how much support a student has had in school when recommending or granting supports and accommodations. It will also be useful to look at personal statements given in CAO forms for background regarding experiences in education, which can be very diverse. 13 2.4 CAO: personal statements The following are excerpts from personal statements collated from CAO applications from 2009: “The main effect my disability has had is its effect on my writing and notetaking. I find that when I am under pressure to write or take notes that my brain moves faster then my hand with the result that I sometimes skip words or letters leave words unfinished or merge the first part of one word with the last part of the next. It also affects my handwriting so that even though I can usually read it other people have great difficulty reading my writing.” “Due to my dyspraxia I have difficulty in processing information quickly leading to periods needed to fully understand and absorb information. My hand writing is slower and less clear than others leading to difficulty in exam situations for both myself and the correcting examiner. My organisation is also affected by my disability leading to great and significant difficulties in recilation organisation if notes and work in prepeartion for exams etc. My dyslexia though mild means spelling and grammer are difficult for myself thus affecting exam results.” “In primary school I was diagnosed with Dyspraxia; during those years I had classes in the CPI unit in Sandymount. From third year in secondary school I attended classes in the resource department. My main problem in class is that I cannot listen and take notes at the same time. I made the decision just to listen in class and when I go home study the textbooks. The resource teachers have tried to help me with note taking and organising my thoughts.” 14 These testimonies all indicate difficulties typically associated with dyslexia, including time management, difficulty with organizing thoughts, slower processing speed and difficulties with spelling and grammar. This highlights that a holistic approach be taken when assessing a student with DCD as other difficulties around producing written work may be present that are not motorrelated. Other personal statements testify to the significance of when the diagnosis is made and interventions put in place. “With assistive technology I have not have encountered too many problems. However before this was provided or allowed I had considerable difficulties completing work on time which hindered my potential.” “Unfortunately I was not diagnosed with Dyspraxia until the beginning of my final year in school. Due to this my dyspraxia had a massive negative effect on my school work until now. All this I feel has left me behind in my class work especially in subjects like history and english where wriiten work compiles the bulk of the subject matter. Dyspraxia has directly affected my motor skills especially my fine motor skills my organisation and time management skills.” These personal statements suggest that intervention at school level can make a positive difference and difficulties with organization and time management skills may be addressed through study skills and/or an occupational therapy model of intervention at second and third level. 15 2.5 TCD: course choices The current student population registered with the Disability as having DCD (whether or not this is co-morbid with any other disability) is as follows: Course College Standing BESS (3 students) 1 Law and French 1 Business and Computing 1 Business and Polish 1 Management Science and Information Systems Studies 1 Foundation Course for Higher Education - Young Adults 1 Religions and Theology 1 Theoretical Physics 1 TSM English and Philosophy 2 TSM Religions and Theology/ Philosophy 2 History 2 Law 2 Philosophy and Political Science 2 Nursing graduand TSM English and History of Art and Architecture graduand Political Science and Geography withdrawn English withdrawn TSM Film Studies and English Literature withdrawn The number of students currently registered for College who are registered with the Disability Service (DS) as having DCD (20) represents 2% of students registered with DS. 16 Within this group of TCD students, practical courses, such as Science and Health Science, are not represented, with the exception of one Nursing student. Faculty breakdown (TCD 2009-10) Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, 18 Health Science, 1 Engineering, Mathematics and Science, 1 A study conducted by Kirby et al. (2008a) comparing course choices between students with DCD and students with dyslexia found that no students with DCD had chosen physical science, health courses or humanities courses in comparison with those with a diagnosis of dyslexia (Kirby et al., 2008b). Kirby (2004) notes that ‘DCD may affect the type of career choices the individual makes, as he perceives himself less able than he may actually be’ (15). Further research could be conducted into reasons for course choices. Kirby et al. (2008) study found that a high proportion of students with DCD study Arts, media and design; Business, Education and Social Sciences, which all come under the Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences category in the table above. The findings are consistent with the representation of this group in courses in Trinity College. 2.6 TCD: retention It is difficult to assess retention rates for this student from such a small group, particularly as a high number of students registered with DS with DCD are in their first year of College. This is indicative of a recent increase in students with DCD accessing third level education, as attested in recent studies. 5 students have progressed to second year and there are two graduands but a high proportion of this group (15%) have withdrawn from College. This small group does not allow for an in-depth study of retention rates but notably there is a high rate of withdrawal even in Junior Freshman year: 17 1 student withdrew from College in Junior Freshman year. 1 student withdrew from College in Senior Freshman year. 1 student withdrew from College having failed to complete requirements for passing Junior Freshman year. 3 students in this group (20%) availed of Academic Support Tuition while no students engaged with Unilink. Both services made contact with students during the academic year to instigate appointments/ check on progress. There was a high incidence of missed appointments and also one student had missed exams. This coupled with a high rate of withdrawal from College indicates that supports for this group need to be re-evaluated. Section 3: Determining appropriate supports for third level 3.1 Specific educational impacts While some studies suggest that children grow out of the difficulties associated with DCD, others, such as Kirby (2010), have noted that the difficulties may just be hidden through persons choosing to avoid environments in which DCD is manifest, such as sports and social activities, such as dancing. As a study by Losse et al. (1991) has revealed a change of environment, such as a new school, can place new demands on the student with DCD which provide new difficulties: ‘Our examination of the school reports of our subjects showed that in some cases the academic and social demands of being in a large school had not only increased their difficulties but had also revealed new ones.’ (66) Denckla (1984) notes: ‘persons given the advantage of training or overpractice on essential motor skills may enter adult life without obvious difficulty unless challenged by new skills to learn’ (cited in Losse et al., 1991, 64). Given these observations it is to be emphasized that third level education provides a completely new set of demands on students, both physical and organizational. 18 3.2 Motor difficulties Colley lists the following motor difficulties that may be encountered by students with DCD: problems using computer keyboards; frequent spills in the laboratory; lack of organization in experiments, difficulty measuring accurately, slow and illegible handwriting, messy presentation (2006: 91). Compensatory strategies for motor difficulties including poor handwriting are available on an online forum which provides useful advice for adults with a number of threads focused on university study (www.dyspraxicadults.org.uk/forums). In many cases the advice given on the forum by adults with DCD is that motor skills improve through practice, reflecting the task-orientated approach, one of the approaches advocated by Gibbs et al. (2007) This approach has been recommended for a number of motor skills for those wishing to pursue Performing arts, sports and music. For some to the pursuit of a particular course in which specific careerrelated motor skills need to be developed, this may be the only approach, but this is not however, always a practical or time-efficient approach for all DCD-related motor skill difficulties. Handwriting is frequently an area of difficulty for students with DCD; Kirby et al. (2008, 208) states that ‘50% of those with DCD stated handwriting specifically as a continuing difficulty.’ A handwriting test may be used to determine the level of supports required although as Summers and Catarro (2003) caution ‘It is difficult to define the parameters by which the degree of disadvantage can be judged as a number of processes may affect written output in an examination.’ (148) Their study concludes that ‘the written output of 66 second-year university students demonstrated that a short duration handwriting speed test was unable to predict written output (number of words) in a 2-hour written examination. (156) There are few standardised tests for handwriting speed. ‘SpLD Working Group 2005/DfES guidelines’ suggest testing writing using a ‘speed of writing prose task’ and a ‘free writing task’: 19 The student’s free writing should be analysed to provide information about ability to write grammatically, the complexity of sentence structure, the coherence of writing, use of vocabulary, writing speed and legibility of handwriting. It is also important to report handwriting speed in a copying task so that difficulties relating to the process of composition and to motor skills can be teased apart (25). The DASH has UK norms for 9-16 year olds and an extension for 17-25 year olds is due to be published in late Spring 2010 (Barnett & Kirby, 2009). This may be used in a third level environment to assess for the need for supports for handwriting difficulties. It must be noted that the application of the guidelines of the SpLD Working Group 2005/DfES guidelines cited above will not give an indication of a student’s ability to take accurate and legible lecture notes and this should be considered if a handwriting test is introduced as part of assessment for third level. Although Summers and Catarro (2003, 156) found that legibility, writing style and fatigue did not appear to influence written output, they found that poor pencil grasp could contribute to a slower writing speed in a three-minute writing task. Students with DCD frequently have a poor writing grip and for lecture note taking, if a student is taking their own notes, this factor should be considered. Ergonomic measures, such as changing furniture, such as level of desk, or using a sloping desk may improve posture and consequently handwriting also, but this may not be possible in a lecture environment. A better pencil grip can sometimes be attained through use of a hand-held ‘stetro grip’ which can be fit onto a roller ball pen. (Sawyer et al., 1993) Experimenting with different types of pen may also be useful, for example fibre tip, rather than biro. Pascoe et al (1993) recommend equipment to assist with pencil grip, including small grips, holders or splints, larger diameter products and weighted or magnetic products. 20 Working on improving handwriting may not be practical for third level students with DCD, particularly if there is a lot of note-taking involved in lectures and this needs to be established early in the academic year. Many will have used computers for exams at second level and may require same at college. However, students with DCD may also have difficulty with keyboard skills and find it difficult to type for extended periods. This may be alleviated by use of a specific ergonomically designed keyboard and use of same in exams. Also an Anir mouse, like a joystick, may be easier to use than a regular mouse (Colley, 2005). Computer skills can also be assessed upon entry to college. Students with DCD may best be supported by a scribe and a note taker during the academic year for lectures, although there is a greater cost involved in providing these services. Colley notes that laboratory work may pose a difficulty for students with poorer motor skills and co-ordination. The task-based approach of improving through practice would not be appropriate here if there were risks involved. In this case a laboratory assistant may be assigned to a student but again this may not be financially viable long term. Students with DCD who undertake to study Nursing should make their Clinical Placement Supervisor aware of any motor difficulties they experience to consider modifications to specialist equipment and/or treatment techniques. Again, it should be determined, ideally prior to entry, whether it is practical to pursue this course depending on motor skills and course requirements and whether the student can be supported sufficiently in the workplace if that would be necessary for specific Nursing tasks. With regard to the requirements of specific courses issues of fitness to practice may be relevant. If a student discloses DCD a risk assessment may be conducted with the student to establish ‘a careful and systematic account of what can cause harm and how this can be prevented’ (TCD, Fitness to Practice 21 guidelines). This may result in the implementation of supports, such as an assistant for laboratory or placement with due consideration given to whether this is deemed appropriate and could be sustained in the workplace and with consideration given to the cost involved in providing this support. 3.3 Non-motor difficulties Third level education entails increased academic and time management demands as students have much more independence than formerly when in school. There are a number of demands that may provide a challenge to students with DCD related to non-motor difficulties. Colley cites potential difficulties with written expression, work organisation, personal organisation, memory and attention span and visual skills, oral skills and numeracy skills. (Colley, 2006: 92-93) Kirby (2004) describes these difficulties as ‘executive dysfunctioning’ and in a study conducted Kirby et al. (2008) 52.4% of a group with DCD reported this as a weakness, which was significantly more than the group with dyslexia (17.4%). The following are the key features of ‘executive dysfunctioning’: Poor cognitive flexibility – difficulty leaping from one idea to another Lack of adjustment of behaviour using environmental feedback – being able to learn from experiences around you Difficulty extracting social rules from experiences – seeing the implied rule rather than the explicit one) the individual may have been in a similar situation before but does not seem to learn from it and ends up making the same mistakes) Difficulty in selecting essential from non-essential information – the individual sees all the information at the same level of importance and finds it hard to ‘sieve’ it according to priority or see what may be risky 22 Impaired working memory – this may make it harder to hold on to several pieces of information at one time and juggle information – the individual also can’t juggle several different tasks at once Difficulty in organisation and completing tasks may prevent the individual even trying to begin the task. (76-77) In a presentation at Trinity College Dublin (March 2010) Kirby outlined how the study skills interventions at third level for students with Dyslexia may not be appropriate for difficulties related to the production of written work, because students with DCD may have further difficulties with ‘executive function tasks’ including time management and organization skills, which can be significantly poorer in students with DCD. Kirby et al. (2008b) carried out a study on three groups of students; those with a self-reported diagnosis of DCD, those with DCD and dyslexia and a third group with dyslexia. This study found the DCD group (54.2%) reported executive functioning as a weakness significantly more than the dyslexia group; problems cited related to organization and memory (208). However, there was no difference in the type of support being given between the three groups. (209) Students with DCD may receive the same supports as those with dyslexia in many cases as often students with DCD received a diagnosis of dyslexia because of lack of standardised assessment tool for DCD. Kirby et al. (2008b) noted that students with DCD often are assessed using tools for dyslexia and the dyslexia-related issues that they experience in addition to any others are sufficient to give a diagnosis of dyslexia, although this results in them perhaps being under-supported or given inappropriate supports. While students with DCD often experience dyslexia-related difficulties a holistic approach that appreciates all the possible motor and organization difficulties associated with DCD should be taken into consideration during assessment. This is particularly relevant in relation to executive dysfunction, the difficulties associated with this being experienced at a higher level by those with just a diagnosis of DCD and dyslexia, and at a much higher level than those with a 23 diagnosis of dyslexia (Kirby et al., 2008b). Kirby has noted that the supports often given to enhance organization skills for this group can be ineffective if they do not easily become automatic skills through habitual use. A support worker may feel that they are supporting a student by giving suggestions around time management and organization but they are of no use if the student forgets to use them. She also noted that time concept was an increased difficulty experienced by students with DCD: ‘The inner clock does not always seem to tick in the same way for the young person with DCD. He may not seem to be aware of time passing. […] The more routine activities are, the less effort they become; this helps to improve time management – see what elements of the day are repeated and create a routine that frees the adolescent to concentrate on the variables in his day’ (Kirby, 2004, 98). Kirby suggested incorporating technology commonly used by young adults as a means of assisting students with organization skills (Kirby, Trinity College, March 2010). Tools such as an iPhone can be utilised for students to access a calendar on a daily basis as it is more likely that this would become habitual and would be something a student would remember to carry with them, rather than a diary. Kirby (2004, 81) notes that a tendency to lose or break things is common with this group and this must be remembered when suggesting or providing supports. The use of a Watch Minder which can be prompted to go off with reminders may be useful (Colley, 2005). The Unilink service in Trinity College Dublin is currently developing a self-management tool in the form of a fold-up booklet that could be utilised for a check-list of daily tasks, which can be wiped clean and re-used. This may be useful as an alternative to technological equipment for this group of students. Kirby noted that a laptop is an expensive piece of equipment to lose or break. It may be advisable to have a note taker attending lectures for students with DCD who find it difficult to take notes or to re-read their handwriting. A Dictaphone may also be useful for recording lectures if suitable for the course, depending on the nature of the material being delivered and also the number of hours of lectures. Poor sense of direction is often associated with DCD and 24 orientation around a new college environment prior to beginning a course may be beneficial to this group. 3.4 Reasonable accommodations A reasonable accommodation is an adjustment to alleviate a disadvantage that a student experiences in the academic environment on account of their disability. This may include any of the following: adjustment to course delivery adjustment to assessment procedures provision of additional services (e.g. notetaker in lectures, extra time in exams) These reasonable accommodations are determined during a detailed needs assessment that is carried out when a student registers with the Disability Service in Trinity College. For students with DCD this should consider the individual, the tasks required in the course selected and the environment in which the student will be learning. A Learning Educational Needs Summary (LENS) is written during the needs assessment which outlines the student’s accommodations provided by the Disability Service and those that are required from the student’s department(s). These may include the following: Provide details of assignment deadlines well in advance. Staff who correct assignments or examinations should refer to Notes on Correcting Scripts written by Students with Specific Learning Difficulties for further information. This information is available on the Disability Service website. Where possible, prioritise reading lists. Provide copies of lecture notes, PowerPoint and overhead slides. These adjustments are designed to make the curriculum more accessible to students and will not confer any added advantage. 25 3.5 Suggested teaching supports Lectures Give clear handouts and Powerpoint presentations following Clear Print guidelines Allow lectures to be recorded Use on-line teaching forums such as WebCT, Blackboard or Moodle. Put lectures up on i-Tunes U. Provided prioritized and annotated reading lists Seminars and Tutorials Be clear as to what will be covered at the beginning of the term. Provide written outline in week one of topics to be covered each week. Be clear as to expectations regarding work to be done for seminars and tutorials. Encourage all students to prepare written notes to bring with them to class to help prompt memory and organize thoughts for discussion. Written work Students may require extra time on account of organization difficulties, but bear in mind that extensions can cause an endless backlog of work. Give sensitive feedback if there is a lot of difficulty evident with written expression. Existing essays and reports can be offered as examples to students. 3.6 Assistive technology (AT) In Trinity College at the beginning of the academic year an Assistive Technology needs assessment is carried out following which the following supports may be suggested/provided: 26 Word processors with good spell and grammar checks. Large monitors Larger, ergonomic mice and keyboards Cushions Pencil grips Screen clamps to move monitor Wrist pad Voice-activated software Text-to-speech software As noted above, some students with DCD find using a keyboard difficult and if handwriting is also difficult it is important for students to develop keyboard skills. Trinity College’s Disability Service runs Touch-Typing Read and Spell (TTRS) course which is a multi-sensory computer-aided course to build touch typing skills while also aiding spelling and writing difficulties. As noted above, there are also larger monitors, ergonomic mice and keyboards with large keys that aid students with difficulties with the fine motor skills necessary for using a computer. An AT assessment will consider the whole study environment for a student and suggest ergonomic supports and equipment to reduce physical fatigue or repetitive strain. These include, chairs with back supports or cushions, wrist supports, screen clamps that can adjust the position of the monitor. These are also available if needed for exams, as are the adaptive equipment for computers (larger screen/keyboard or ergonomic mouse). 3.7 Academic Support A number of studies have shown that students with DCD have difficulties with reading and writing skills; a study conducted by Dewey et al. (2002) found that the DCD group scored significantly lower than the comparison group on all 4 measures of reading skills (Letter Word Identification, Passage Comprehension, Reading Vocabulary, Word Attack) and all 7 measures of writing skills (Dictation, Writing Samples, Proofreading, Writing Fluency, Punctuation and Capitalization, 27 Spelling and Word Usage). Their study was conducted on children but it is likely that difficulties in these areas are likely to continue to adulthood and that students should be given the opportunity of working on these skills with a tutor on an ongoing basis. As noted above the provision of support in this area needs to be carefully tailored to meet the needs of individual and assessed during regular meetings with the student. In Academic Support currently, the practice to date has been to carry out a needs assessment which identifies areas that the student foresees as being difficulties. This includes analysis of the student’s learning style by carrying out an on-line learning style survey such as VARK or the DVC Learning Style Survey. Areas of prospective difficulty are discussed and prioritized and a subsequent appointment is made to begin to work on these. The onus is on the student to make appointments subsequently. In future during the needs assessment the Academic Support Tutor will focus on the course requirements as per student handbook and identify when coursework and exams are due. Subsequently, the Academic Support Tutor will make contact with the student to arrange half-hour appointments and take a more task-based approach to providing support, focusing on specific areas, such as using the Library, note taking, referencing, database research, essay structure. Regular follow up contact will be made. 3.8 Unilink (OT-based one-to-one support) Unilink is an OT-run one-to-one support service for students with disabilities. Unilink 1 supports students with mental health difficulties, while Unilink 2 caters for students with physical, sensory, chronic health or specific learning disabilities. Students with a primary diagnosis of Dyspraxia/DCD can be referred to the Unilink 2 service for support in meeting the varying demands placed upon them in their student role. An initial appointment will establish the tasks required of the students in College using a profile form to assess self-care, productivity and leisure tasks and goals. The student will identify and prioritize areas of difficulty on which they wish to work and follow up meetings will identify and prioritize 28 weekly tasks. Where tasks are specifically related to research skills, use of Library or producing written work a referral to AST may be made. As noted above, there is a high rate of no show/cancellation. It is not considered practical to require students to meet weekly but in order to minimise no shows and cancellations Unilink staff will email next appointment when it has been agreed and also text reminders in advance to students of appointment times at the beginning of the day of the appointment. Kirby identified that executive functioning is one significant difficulty. Kirby also cautions that when implementing supports it is important to consider what can be easily made habitual for students with DCD. It is proposed that in future Unilink will suggest various strategies for time management, including (where appropriate) using an iPhone calendar, myzone calendar, wall planner or Unilink 2 handbook. The approach taken will give the student more involvement in their self-management and regular follow-up appointments will assess how well this has been taken up by the student and change strategy if necessary. Unilink will also address ergonomic issues with students with DCD if there are issues with posture, handwriting or use of technological equipment that could be causing pain or fatigue. Gibbs et al. (2007) emphasize the psychological and social issues associated with DCD in childhood and recommend psychological supports particularly for transitional times such as the move from primary to secondary education. In adulthood it is more likely that students accessing third level education have developed social skills and a study conducted by Kirby et al. (2008) found that 45.8% of the group with DCD reported social skills as a perceived strength. It must, however, be remembered that many social aspects of third level involve physical activity; many societies are sports related and dancing and drinking alcohol are often key social elements for this age-group. Many of these activities provide or exacerbate difficulties for students with DCD and this should be considered during assessment upon entry to college. A meeting with an OT- 29 based support service may be appropriate to find ways of helping students with DCD integrate socially into college life. If a College does not have this kind of service Learning Support should adopt the same approach and ensure that they maintain regular contact with students with DCD and re-evaluate the supports provided or suggested, as necessary. Difficulties in this area could be a significant contributory factor to a student’s decision to withdraw from college. Unilink staff take this aspect of College life into consideration during the first meeting with a student and will consider with the student with DCD various social options in College, including gym, sports, societies and social activities that do not tax motor skills or may involve a task that can be mastered. Summary of recommended interventions (AT, Learning Support and OT service) Motor skill difficulties Interventions Handwriting Pencil grips Experiment with different pens Computer and use of keyboard Build computer and touch typing skills Provide ergonomic supports, such as cushions, wrist supports, back supports, screen clamps, ergonomic keyboard and/or mouse 30 Writing skills Interventions Structure and writing skills Prioritize areas of difficulty in the production of written work Provide carefully tailored academic support building on the student’s learning style and strengths as indicated by on-line test, such as VARK or DVC Learning Style Survey Organization and Social Skills Interventions Organization Analyse options for organising timetabling using a calendar or diary, incorporating technology where appropriate and where it can best be made habitual. Social Skills Discuss social options available to student within and without College that may avoid the student’s motor difficulties and build on their strengths. Section 4: Summary 4.1 Discussion Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) has only recently been distinguished in the CAO application process as a distinct group from Specific Learning Difficulty. This emerging population at third level has a set of needs which frequently overlap with other developmental disorders but should also be considered as distinct from the difficulties traditionally associated with Specific Learning Difficulty (eg. Dyslexia). This study recommends that a holistic 31 approach be taken at needs assessment and by those providing supports to consider motor and non-motor difficulties and, as stressed by Kirby, difficulties with executive functioning (organizational tasks). It should be remembered that supports that are traditionally recommended by learning support tutors for students with Specific Learning Difficulties may not be appropriate on account of the fact that they may not be learned by students with Developmental Coordination Disorder. It is recommended that appropriate AT supports be used as interventions but that this be supplemented with regular, timetabled one-to-one tuition to assess the suitability of supports and consider not only their appropriateness but whether or not use can be made habitual. Currently there is a strong trend of students with DCD at Trinity College pursuing Arts and Humanities courses but as this is an increasing population thought should be given to supporting students with DCD who wish to pursue more practical courses that may involve tasks that require a high level of manual dexterity, such as using Nursing equipment or laboratory work. Supporting these students may be against the student’s interest on account of fitness to practice requirements for the career that the course leads to and the costs involved in supporting the student, for example, the provision of a laboratory assistant. 4.1. Further Research As noted in this study, it is difficult within the present group in TCD to study progress and retention on account of the low number of students with DCD currently registered with the College Disability Service. Students with DCD may have entered College with a report confirming Specific Learning Difficulty as it is only in 2008 that the DCD group was distinguished as a distinct group by the DARE process of application. Further research could be conducted in the future or with a wider population to study progress and retention of students with DCD at third level. 32 Regarding course choices, TCD shows a similar trend to the findings of a study by Kirby et al. (2008a). There is a strong trend toward Arts and Humanities subjects, but given that it is now recognized as a distinct group and that this emerging population is growing rapidly, it is more likely that in future students with DCD will be applying and accepted for a wider spectrum of courses and this may include courses with a manual element that requires physical dexterity that could challenge students with DCD who have motor difficulties. Further research could be undertaken to consider how to support students in courses with laboratory or placement work as the provision of a personal assistant would be difficult to implement on account of funding constraints. This is also an area of study to consider under issues of fitness to practice. References Barkley, R. A., Fischer, M., Edelbrock, C. (1990) The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: an 8-year prospective followup study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 29, 546 -557 Barnett, A.L. & Kirby, A. (2009) Students with DCD in further & higher education: a primer for assessors Bruininks R.H. (1978) Bruininks-Oseretsky test of motor proficiency examiner’s manual. Circle Pines, Minnesota: American Guidance Service. Cantell, M.H. Smith M.M. & Ahonen, T. Clumsiness in adolescence: Educational, motor and social outcomes of motor delay, detected at five years. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 11, 115–129. 33 Colley, Mary. (2006) Living with dyspraxia: a guide for adults with developmental dyspraxia; foreword by Victoria Biggs; introduction by Amanda Kirby. London: Jessica Kingsley. Colley, Mary. (2005) Learning support for students who are dyspraxic. In De Montfort University, Neurodiversity in FE and HE: positive initiatives for specific learning differences. Proceedings of two one-day conferences. De Montfort University, Leicester. 33-46 Cousins, M. & Smyth M. M. (2003) Developmental coordination impairments in adulthood. Human Movement Science 22, 433-459. Dare, M.T. & Gordon, N. (1970) Clumsy children: A disorder of perception and motor organisation. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 12, 178-185. De Montford University (2005) Neurodiversity in FE and HE: positive initiatives for specific learning differences: proceedings of two one-day conferences. Leicester: De Montfort University. Department for Skills and Education (2005) SpLD working group guidelines. Nottingham: Department for Skills and Education Publications. Dewey D., Kaplan B.J., Crawford S.G., Wilson B.N. (2002) Developmental coordination disorder: Associated problems in attention, learning, and psychosocial adjustment. Human Movement Science, 21 (5-6), 905-918. Dewey, D. Wilson, B.N. Crawford S.G & Kaplan, B.J. Comorbidity of developmental coordination disorder with ADHD and reading disability. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 6 (2000), 152-153 34 Dixon, Gill and Lois M. Addy. (2004) Making Inclusion Work for Children with Dyspraxia: Practical Strategies for Teachers. London; New York, NY: Routledge Falmer. Geuze R.H. and Börger, H. (1993) Children who are clumsy: Five years later. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 10, 10–21. Gibbs, J. Appleton, J. & Appleton, R. (2007) Dyspraxia or developmental coordination disorder? Unravelling the enigma. Arch Dis Child 92, 534-539. Gillberg C. & Kadesjö B. (2000) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and developmental coordination disorder. In: T.E. Brown, Editor, Attention-deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents, and adults, American Psychiatric Publishing, Washington, DC, US, 393–406. Gillberg, C. (1998) Hyperactivity, inattention and motor control problems: Prevalence, comorbidity and background factors. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopedia 50, 107–117. Gillberg C. & B. Kadesjö, B. (1998) AD/HD and developmental coordination disorder. In: T.E. Brown, Editor, Attention deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents and adults, American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC. Gillberg C. & Rasmussen P. (1982) Perceptual, motor and attentional deficits in seven-year-old children: background factors. Dev Med Child Neurol. 24(6): 752– 770. Gillberg, C. Rasmussen, P. Carlstrom, G. Svenson B. and Waldenstrom, E. (1982) Perceptual, motor and attentional deficits in six-year-old children: Epidemiological aspects. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 23, 131– 134. 35 Geuze, R.H. & Börger H. (1993) Children who are clumsy: Five years later. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly 10, 10–21. Gubbay, S. S. (1975).The Clumsy Child—A Study of Developmental Apraxic and Agnosic Ataxia. W. B. Saunders, London. Hellgren, L., Gillberg C. & Gillberg, I.C. (1994) Children with deficits in attention, motor control and perception (DAMP) almost grown up: The contribution of various background factors to outcome at the age of 16 years. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 3, 1–15. Henderson, S. E. & Sugden, D. A. (2007) Movement Assessment Battery for Children. Second Edition. London, The Psychological Corporation. Kadesjö B. & Gillberg, C. (2001) The comorbidity of ADHD in the general population of Swedish school-age children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 42, 487–492. Kadesjo, B. & Gillberg, C. (1999) Developmental coordination disorder in Swedish 7-year-old children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 820-828. Kadesjö B. & Gillberg C. (1998) Attention deficits and clumsiness in Swedish 7year-old children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 40(12): 796-804. Kaplan, B.J. Crawford, S.G. Wilson B.N. & Dewey, D. (1997) Comorbidity of developmental coordination disorder and different types of reading disability. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 3, 54. 36 Kirby A. Edwards L. Sugden D. & Rosenblum S. (2010) The development and standardization of the Adult Developmental Co-ordination Disorders/Dyspraxia Checklist (ADC) Research in Developmental Disabilities 31(1), 131-139. (a) Kirby A., Sugden D., Beveridge S. & Edwards L. (2008) Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) in adults and adolescents in further and higher education. Journal of Research in Special Education Needs, 8,120-31. (b) Kirby, A., Sugden, D., Beveridge, S., Edwards, L. & Edwards, R. (2008) Dyslexia and Developmental Co-ordination Disorder in Further and Higher Education - Similarities and differences. Does the 'Label' influence the support given? Dyslexia, 14(3), 197-213. Kirby A. Salmon G. & Edwards L. (2007) Should Children with ADHD be Routinely Screened for Motor Coordination Problems? The Role of the Paediatric Occupational Therapist British Journal of Occupational Therapy 70(11), 483-6. Kirby, A. (2004) The adolescent with developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) London: Jessica Kingsley. Landgren, M., Kjellman, B., Gillberg, C. (1998) Attention deficit disorder with developmental coordination disorders. Arch Dis Child 79(3), 207-12. Loeber, R. (1982) The stability of antisocial and delinquent child behavior: a review. Psychology Bulletin, 94, 68 -99. Losse, A., Henderson, S.E., Elliman, D., Hall, Knight, E. and Jongmans, M. (1991) ‘Clumsiness in children: Do they grow out of it? A 10-year follow up study.’ Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 33, 55–68. 37 Martini, R. Heath N. & Missiuna, C. (1999) A North-American analysis of the relationship between learning disabilities and developmental coordination disorder. International Journal of Learning Disabilities 14, 46–58. Morrisby, J. (1991). Morrisby profiler: Dexterity. Hertfordshire: Educational & Industrial Test Services Ltd. Pascoe, J. Gore, S. Lindsay, McLellon, D (1993) Equipment to Assist with Pencil Grasp. Handwriting Review 49-62. Peters, J. M. & Henderson, S. E. (2008) Understanding developmental coordination disorder (DCD) and its impact on families: the contribution of single case studies. In: D. A. Sugden, A. Kirby & C. Dunford (Eds) Special Edition of the International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 55, 97-113. Politajko, H. (1999). Developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD) alias the clumsy child syndrome. In Whitmore, K., Hart, H., & Willems, G. (Eds) Neurodevelopmental approach to specific learning disorders (119–134). London: Mac Keith Press. Portwood, Madeleine. (2000) Understanding Developmental Dyspraxia: A Textbook for Students and Professionals. London: David Fulton. Poulsen, A.A. Ziviani, J.M. & Cuskelly, M. (2007) Perceived freedom in leisure and physical co-ordination ability: impact on out-of-school activity participation and life satisfaction (2007) Child Care Health Dev. 33 (4), 432-40. Rasmussen P. & Gillberg, C. (2000) Natural outcome of ADHD with developmental coordination disorder at age 22 years: A controlled, longitudinal, community-based study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39, 1424–1431. 38 Sawyer, C.E. Francis, M.E. Knight E. (1992) Handwriting Speed, Specific Learning Difficulties and the GCSE. Educational Psychology in Practice, 8, 77 81 Smits-Engelsman, B.C.M. Niemeijer A.S. & Van Galen, G.P. (2001) Fine motor deficiencies in children diagnosed as DCD based on poor grapho-motor ability. Human Movement Science 20, 161–182. Taylor, E., Sandberg, S., Thorley, G., (1991) The Epidemiology of Childhood Hyperactivity. Oxford University Press. Visser, J. (2003). Developmental coordination disorder: A review of research on subtypes and comorbidities. Human Movement Science, 22, 479–493. Wann, J.P. Mon-Williams M. & Rushton, K. (1998) Postural control and coordination disorders: The swinging room revisited. Human Movement Science 17, 491–514. Williams H. & Woollacott, M. (1997) Characteristics of neuromuscular responses underlying posture control in clumsy children. Motor Development: Research and Reviews 1 (1997), 8–23. 39